The Duck-Rabbit & the Polarities of Leadership

A polarity is a paradoxical situation in which two interdependent and seemingly contradictory states must be maintained for success over time. In business, leadership and life, we find ourselves presented by polarities all the time, often without even realising.

As leaders, we’re told that we must be great problem solvers. That’s true, but a polarity is not the same thing as a problem, for which a definitive solution can be reached at a given point in time. That’s why the ability to recognise when we are facing a polarity – otherwise known as a paradox, duality, dichotomy, tension, or wicked problem – can be a developmental leap for leaders. Embracing the polarities we face with a both/and mindset, as opposed to trying to solve them as problems with an either/or approach, opens up whole new ways forward.

In this article, we’ll meet a number of leaders who are facing polarities at work. We’ll focus on Shrupti, the founder and CEO of a crypto analytics business. We’ll unpack how she identified and navigated a polarity that was holding her leadership and business back. With these practical examples, you too will gain a greater understanding of how you can identify and work more effectively with polarities.

Wittgenstein used a duck-rabbit image in his Philosophical Investigations (1953). The duck-rabbit optical illusion is a paradox, because it is both one thing, and another, at the same time.

Click to jump to a section:

A brief history of polarities

Evolution has wired us for black and white thinking. When the bush next to our ancestors moved, it was much safer for them to assume there was a dangerous animal behind it about to burst out and eat them than it was to risk the asymmetric outcome of hanging around to find out. A nuanced consideration of all the reasons why the bush was moving didn’t serve us well.

From an evolutionary perspective, the brain is masterful at either/or thinking, and it doesn’t like the nebulousness of both/and. From the earliest times, the brain has had to quickly determine if something was safe or dangerous. Seeing things in opposition is hard wired into our brains, which makes it completely logical and understandable that we would have to work harder to hold a both/and mentality.

Navigating Polarities: Using Both/And Thinking to Lead Transformation, by Brian Emerson & Kelly Lewis

The ancient Chinese worked out that the world isn’t as binary as this. Connecting with the philosophy of Yin-Yang around 500 BC, they sought to find a balance between seemingly opposing forces so that they are unified, in order to be productive holistically. They noticed the relationships and patterns that occurred in nature and they believed that the world environment to be a harmonious and holistic entity.

Yin and yang, male and female, strong and weak, rigid and tender, heaven and earth, light and darkness, thunder and lightning, cold and warmth, good and evil…the interplay of opposite principles constitutes the universe.

Confucious

The Ancient Greeks understood this too. Socrates proposed that everything that comes to be, comes to be from its opposite. Many of Aristotle’s virtues focus on taking two opposite extremes and maintaining the right blend of both.

Whilst our brains remain hardwired to our ancestral way of thinking, philosophically we understand that this doesn’t always serve us well. The issues upon which our ‘survival’ depends have largely changed. Our increasingly complex and uncertain world is full of both/and choices. To navigate it we need to loosen our attachment to either/or thinking and embrace both/and.

Emerson & Kelly Lewis explain that the interdependence of a polarity requires both/and thinking. If we ignore one in light of the other over the long term, we end up in a bad situation. The emphasis here is ‘over time’: it might be possible to focus on just one pole in the short term, but in the long run, if we want to be successful, we’ll need both.

Barry Johnson, who first introduced his ideas around polarities nearly 50 years ago, brought this to life with a simple example: breathing. Both inhaling and exhaling are essential for life. Either inhaling, or exhaling, won’t keep us alive for more than a few minutes. We require a careful balance of both to survive and thrive. In essence, this is how all polarities work.

Working seperately from the likes of Johnson, Emerson and Lewis, business strategist Roger L. Martin has written about the differences he’s observed between what he calls conventional and integrative thinkers. In The Opposable Mind: Winning Through Integrative Thinking he identifies four traits:

- More salient features make for a messier problem, but integrative thinkers don’t mind the mess. In fact, they welcome it because the mess assures them that they haven’t edited out features necessary to the contemplation of the problem as a whole. They welcome complexity because they know the best answers arise from complexity.

- They don’t flinch from considering multi directional and non-causal linear relationships simple uni-directional relationships are easier to hold in mind, but they don’t generate more satisfactory resolutions.

- They allow complexity to compound as they design their decision’s. The complexity presents a cognitive challenge that integrative thinkers welcome, because they know that complexity brings along in its train an opportunity for a breakthrough resolution.

- They always search for creative resolution of tensions, rather than accept unpleasant tradeoffs.

Examples of business & leadership polarities

The leaders I have studied share at least one trait, aside from their talent for innovation and long term business success. They have the predisposition and the capacity to hold two diametrically opposing ideas in their heads. And then, without panicking or simply settling for one alternative or the other, they’re able to produce a synthesis that is superior to either opposing idea.

The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking, by Roger L. Martin

Have you found yourself facing similar challenges to the leaders below?

Shrupti is the CEO at a scaling crypto analytics platform that recently raised $90 million. She wants to empower her team to take charge of their workstreams, to grow the business she founded in accordance with her vision. But she knows that she can get too involved. She recently had a run-in with her COO who told her they felt choked by her constant interferring. How can Shrupti interfere less in the work of her leadership team, whilst at the same time trust and empower them to translate her vision into reality?

Tim is a partner at a top-tier venture capital firm. The firm’s impressive investing track record is becoming offset by its reputation for long working hours, which is impeding talent attraction and retention. Three team members have recently taken time off for burnout. The managing partner has asked Tim to explore how they should respond to this. Is it possible to balance high performance with employee well-being and a less intensive culture?

Wesley is the CEO of a fintech business that has grown to 250 people in just 4.5 years. He credits this success to his decisiveness and followership. But recently he’s made some bad calls that have seriously impacted top line growth. 360 feedback undertaken by his executive coach revealed that many people would like to see more humility from Wesley. How can Wesley balance the confidence that has got the business to where it is with the humility to accept that he doesn’t know everything?

May is the Executive Vice President of a division of a global technology business that was recently acquired. It’s going through a major re-structure, leading to a lot of uncertainty amongst her 2,000 person team. Despite reassurances from her CEO, May is nervous about her own future. She is delivering a Town Hall next week, announcing further changes, including lay-offs. She has always prided herself on her vulnerable leadership style but she senses that the whole team need a leader that exudes confidence and certainty right now. How does May ‘show up’ at the Town Hall in a way that respects her vulnerable leadership style whilst at the same time demonstrating that she’s on top of this transition?

Brian is CTO at a B2B SaaS business. He’s leading the recruitment drive to onboard 15 new engineers over the next 6 months. Speed is of the essence, to keep up with growth plans. He’s received lots of outstanding applications but most of them are white males, just like him. He knows he could recruit all these individuals and they’d do a great job but this would likely lead to all sorts of DE&I challenges. How can Brian recruit quickly whilst at the same broadening the pipeline of more diverse applicants?

Here are some other common polarities you might have experienced, or are currently grappling with:

Servant Leadership :: Heroic Leadership

Grounded :: Visionary

Leader as Coach :: Command & Control

Empower :: Direct

Support :: Challenge

Reflection :: Action

Diplomacy :: Candor

Realistic :: Optimistic

Lead by Example :: Delegate Effectively

Manager :: Leader

Ask the Right Questions :: Have the Answers

Listen Intently :: Communicate Confidently

Support Team :: Provide Freedom

Be Inclusive :: Be Decisive

Embrace Complexity :: Keep it Simple (KISS)

Open-minded :: Paranoia

Risk :: ResultsHolocracy :: Hierarchy

Centralization :: Decenralization

Structure :: Flexibility

Continuity :: Change

Survive :: Grow

Quality :: Cost

Individual :: Team

Team :: Organisation

Process :: Results

Stick to Plan :: Iterate & Learn

Collaborate :: Compete

Top Down Innovation :: Bottom Up Innovation

Work From Home :: Be in the Office

You’re reading one of my most popular articles. Here’s more:

How do you show up as a senior leader? Take A fresh look at executive presence.

Get a grip on your diary with 8 Time Management Techniques for Leaders (based on real CEO coaching conversations).

How Vertical Development helps new leaders transform explores the distinction between horizontal development, which focuses on what you know, and Vertical Development, which concerns how you think.

How you can embrace both/and thinking to navigate polarities

How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress.

Niels Bohr

Let’s return to Shrupti, the CEO of the crypto analytics platform who is getting too involved in the work of her Leadership Team (LT) and add some more context. Shrupti wanted to understand how she could interfere less in the work of her leadership team, whilst at the same time trust and empower them to translate her vision into reality?

A conversation with her executive coach prompted some realisations for Shrupti:

- She was micro-managing – not letting her experienced and well-paid team get on with the work they had been recruited to do. She had the self-awareness to know that if she wanted to scale with her business, she needed to do less and lead more. But how?

- She lacked previous experience of leading executives – before founding the company, Shrupti had only previously managed a team of twelve people. She wasn’t sure what the boundaries of her responsibility were and, even when she had more clarity, she was struggling with how to delegate.

- The business was tied to her identity – Shrupti recognised that she thought only she knew what was best for it. When she saw her leadership team doing things she wasn’t comfortable with she felt compelled to intervene. She often felt that they weren’t meeting her high standards and were putting the success of the business at risk. When pressed by her coach, she acknowledged that his was just a feeling, not necessarily a fact.

- She had hiring anxiety relating to her COO – her last one had proved ineffective. She didn’t remove them quickly enough and, in the end, her Board told her that they had to go. Had she made the wrong hire again? What were her Board thinking this time? Did they see Shrupti as weak and ineffective? All these concerns meant Shrupti meddled in her current COO’s work even more.

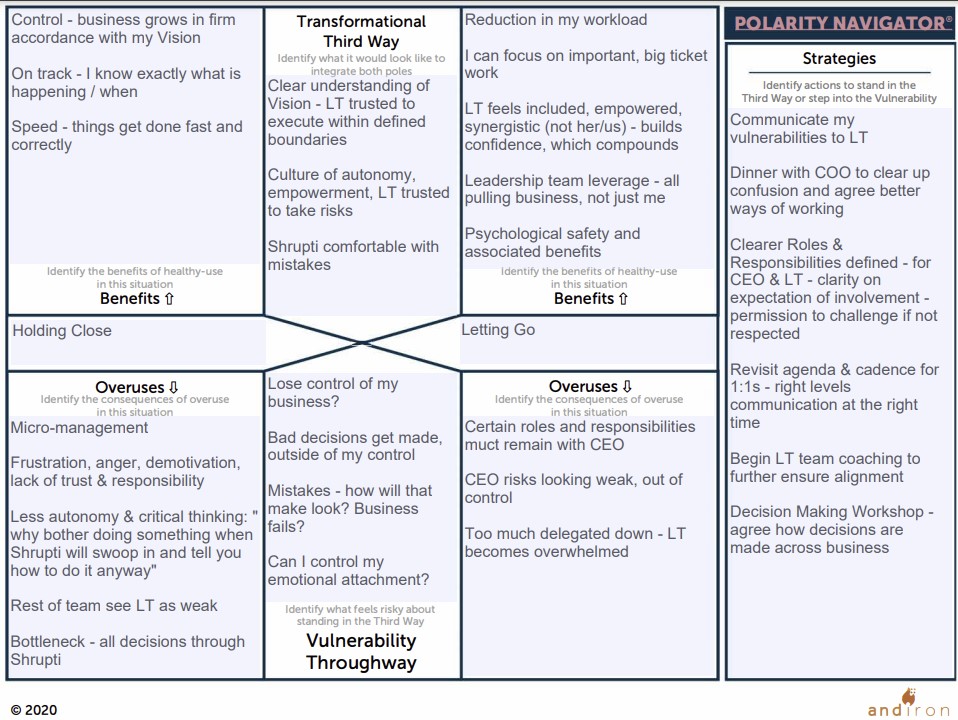

Her coach pointed out to her the tension in her leadership style between holding her business closely and letting go of responsibilities to her leadership team. The coach suggested that they jointly work through a Polarities Navigator, a sensemaking tool that helps leaders organise complex ideas and find a Third Way through. Shrupti’s Polarities Navigator is below.

Naming the poles allowed Shrupti to ‘hold them up’ and explore them from different angles: Holding Closely :: Letting Go.

This new perspective gave her the opportunity to make object (having the capacity to reflect, handle, look at, be responsible for, relate, take control of, internalise and assimilate) situations to which she might otherwise have remained subject (those elements of our knowing or organising that we are identified with, tied to, fused with, or are embedded in).

The capacity to work with with polarities and self-relate in this way are two of the four ‘vertical’ skills that help leaders to thrive in complexity. Read 4 vertical leadership skills to help you thrive in a VUCA world to learn about the other two.

Exploring the Benefits and Overuses of each meant pole she could identify the good things that holding her business closely brought, but also the problems that came from doing it too much. Likewise, she could do the same for letting go. This is important because of a number of foundational polarity concepts:

- Neither pole is absolutely good, or absolutely bad

- They are interdependent and need each other over time

- They are not problems to be solved, rather relationships to be managed

With that enhanced perspective, she leant deeply into her emotions and what was driving them. She realised just how closely her identity was tied to the business. She recognised how her lack of leadership experience and failure to remove her last COO fast enough were worrying her. Opening up and exploring about these Vulnerable Throughways was cathartic and helped her imagine what a Transformational Third Way through might look and feel like.

Standing in the Third Way is a commitment to personal development, to growth, and to being with the truth of the interdependent relationship. We have to develop the mental clarity, emotional stability, and embodied presence to not be swept up in the natural cycle of the infinity loop – the ups and downs, values and fears. When we can do that, we step into a mindset and way of being that is fluid, not fixed, trusting, adaptable, and responsive… No longer are we pushed or pulled; no longer do we feel the need to choose one or the other; no longer do we identify who we are by our preferred pole. As we reconcile these seemingly opposite forces and we allow them to be harmonized within ourselves, we are moved by the extraordinarily simple and subtle force of the Third Way.

Navigating Polarities: Using Both/And Thinking to Lead Transformation

Shrupti identied specific Strategies to help her navigate the polarity in a way that respected both poles – her ambitious vision and the need for an aligned leadership team who could help her deliver it. She opened up to her team about her vulnerabilities and was overwhelmed by the supportive responses. She took her COO for dinner, leading to all sorts of realisations, on both sides, about why the relationship had not been working effectively. The C-team agreed an improved cadence to their one-on-ones with Shrupti and leadership team meetings. Roles and responsibilities were re-visited and ‘permission’ given by all to feedback directly when they felt intrusions into their work by others. A Decision Making Workshop was held. The C-team worked with a leadership team coach who added another level of consistency and alignment.

Problem? Pause. Polarity?

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Not everything is a polarity. If the building is on fire, you need to get out fast. In business, if you’re exploring international expansion and you only have budget to move into one country then that doesn’t mean you should split the difference and half-launch in two places. When it comes to ultimately making a choice about a new hire, you have to decide whether it’s person A or person B.

Great leaders can solve problems and act decisively when the situation requires it. On other occasions, they can appreciate nuance and hold competing tensions before identifying a way forward. If you’re honing this capacity, the hardest part is often identifying what sort of challenge you are facing:

The most effective way to build the muscle of spotting polarities is to create the habit of simply pausing when in a problematic situation and asking “Could there be a polarity here?” We are wired to jump to action, and many of us are experts at doing it quickly! When faced with any issue, simply taking the time to consider whether or not it is a polarity is a crucial step.

Remember the three Ps: Facing a Problem…take a Pause..is it a Polarity?

Navigating Polarities: Using Both/And Thinking to Lead Transformation

With thanks to:

Brian Emerson, Anne Nagle and Mike Vessey for introducing me to polarities at the beginning of lockdown and training me in the use of the Polarities Navigator. Once your eyes are open to polarities you start seeing them all around you. Helping coaching clients identify polarities not immediately obvious to them, and supporting them to navigate their own way through is very rewarding.

Niko Canner for orginally inspiring this piece. In The Duck-Rabbit and the Art of Entrepreneurship, Canner points out that anyone who has built a company knows what it’s like to flip back and forth between just knowing that what they’ve pictured in their head really will get realized in the world and despairing that the latest just-maybe-insurmountable obstacle could derail the venture entirely. Like the Duck-Rabbit, the practice of entrepreneurship has two sides that can be very difficult to experience together:

- The conviction that the ultimate goal can and will be achieved, inspiring purposeful, decisive action toward that distant future; and

- Self-critical assessment that acknowledges what is likely to be required to achieve the goal—the ability to regard with clinical accuracy the immense gap between those requirements and one’s current resources, capabilities and vision.

Ed Batista, who also coaches CEOs of growing companies. In The Cognitive Dissonance of the CEO, he explains a theme that regularly shows up in his work with many of them – the stress that results from simultaneously maintaining two very different views of the world:

Because my clients are constantly raising money from investors, or recruiting senior employees, or closing deals with major customers, they must be exuberant optimists, portraying a compelling vision of a successful future. And because the possibility of failure remains quite real – and those investors, employees, and customers will ask tough questions before signing up – my clients must also be keenly aware of the nearly endless list of risk factors and things that could go wrong, sometimes to the point of inducing anxiety.

I’m Richard Hughes-Jones, an Executive Coach to CEOs and senior technology leaders.

My clients are transitional founders, CEOs and executives in high-growth technology businesses, the investment industry and progressive corporates.

Having often already mastered the technical aspects of their craft, I help my clients navigate the complex adaptive challenges associated with executive-level leadership and growth.

Find out more about my Executive Coaching services and get in touch if you’d like to explore working together. You can also read my Complete Guide to Finding the Right Executive Coach for You.