How I Read – Non-Secrets for Voracious Reading

People sometimes ask me, “Rob, how do you read so much?” or “How many books do you read simultaneously?” or “What is your reading plan?” or even “How do you get through so many books, are you a speed reader?” (I’m not).

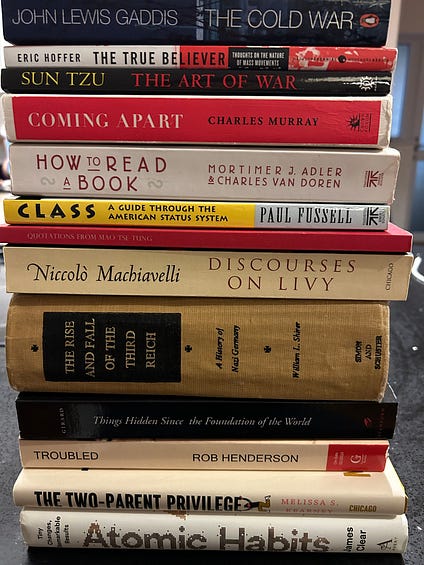

Readers and Twitter/X followers see how frequently I post my readings or see my recommended books and assume there must be a secret.

There’s no secret.

I read pretty slowly. I take notes, I underline, I highlight, I jot my thoughts in the margins, I pause if I encounter an especially interesting passage or idea.

Years ago, I read How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler. He described reading a book as being “in conversation” with the author. But reading has the added benefit of allowing you to concentrate deeply, move as fast or as slowly through an argument or idea as you want, and formulate and reformulate your thoughts as you move through the text.

In a given year, I read about 40-50 books cover to cover, read excerpts and chapters of perhaps another 100 or so, and skim many more. I also read psychology papers and other academic texts.

I read multiple books concurrently. Typically 2 or 3 physical books I cycle through, with one I devote most of my attention to. I also have 2 other books I read on the Kindle app on my phone. Waiting in line at the store. In between sets at the gym. Traveling on the train or an uber. All this time adds up. You can spend 5 or 10 minutes scrolling, or read a couple of pages of a good book. I recommend the latter.

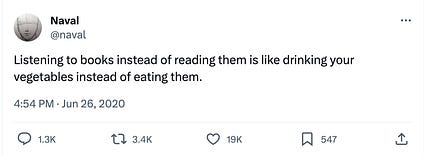

What about audiobooks? I like this post from Naval Ravikant:

He’s right.

Reading requires a lot of effort and practice. Hearing language versus reading it engages different mental processes. Reading forces you to move more slowly. If an author explains an idea to you, the constraints of natural conversation mean that you can’t just pause for 10 minutes while you think deeply about what he or she just said and then subsequently resume the discussion. Books enable you to do that. Of course, you can pause on audiobook and think about what the author just said. Often, though, listening to audiobooks is accompanied by other tasks, making it harder to devote 100% of your attention to the ideas being discussed or the story being told.

Listening to audiobooks is easier. And it’s better than nothing. But if you want to seriously engage with ideas and increase the likelihood that you’ll retain knowledge, it’s better to read.

Byrne Hobart writes:

“You will not learn anything of lasting importance from TV, movies, podcasts…they’re junk food. Successful people converge on 3 ways to learn: lots of reading time, some exercises and projects, and conversations with people who are slightly ahead of them.”

I regularly listen to podcasts; I watch movies and TV shows. They can be stimulating and provoke interesting thoughts, but they are not the same thing as reading.

A similar perspective from Tyler Cowen:

Dwarkesh Patel: Okay. Let me ask a meta question. What do you think podcasts are for? What is happening?

Tyler Cowen: To anaesthetize people? To feel they’re learning something? To put them to sleep. So they can exercise and not feel like idiots. Occasionally to learn something. To keep themselves entertained while doing busy work of some kind.

Dwarkesh Patel: Is this the same as the anesthetizing?

Tyler Cowen: You want to feel you’re imbibing the most important ideas, and there are very costly, tough ways to do that. For example: to actually work on one of those problems as a researcher. But most people can’t do that (through no fault of their own). Even if they’re academics, maybe they just can’t do it. So one of the next best things is to listen to someone to at least pretend that they’ve done it. And it’s okay, it’s a substitute. Like, why not? What are you supposed to do? Watch TV?

Dwarkesh Patel: Okay, but is your own podcast a complement to actual intellectual inquiry?

Tyler Cowen: I don’t assume that it is. I think of it as a very high-class form of entertainment.

“Very high-class form of entertainment.” More flattering than “junk food.”

Finally, Janan Ganesh writes:

“People are willing to do almost anything other than read at length…At the same time, no one relishes being ignorant or incurious…One way of squaring these opposing impulses is to give things that aren’t books the intellectual status of books.”

In our busy and distracted society, deep reading is increasingly rare. Deep reading changes people. When you interact with people, you can tell who reads seriously and who doesn’t. This isn’t just a matter of mental ability or intelligence. There is a difference between raw cognitive horsepower and time spent immersed in complex and intricate ideas. You can tell the difference between a smart person who reads and a smart person who doesn’t by how they express ideas, the references they make, and the chains of logic they follow. The former often demonstrates a subtle understanding that weaves together insights from various domains. The latter, though sharp and quick-minded, lacks the same depth of perspective or the ability to see beyond the immediate conversation or the Current Thing. This is becoming increasingly apparent among obviously bright young adults who don’t read or read nonsense despite paying large sums of money for what should have been a decent education.

I listen to podcasts. Often, though, I’ll listen to them to supplement or reinforce what I’m reading. So if I’m reading a book by, say, Melissa Kearney, I’ll also listen to her interviews. This helps the information to stick.

Don’t get me wrong—I listen to comedy podcasts and fun stuff too. But I try to reserve that for the end of the week or weekends.

Reading takes time. You have to make it a non-negotiable part of the day.

This precious time must be guarded! Some thinkers, as they rise in prominence as a result of their interesting ideas, gradually devote less time to reading and more time to lucrative opportunities. This is a mistake. They are neglecting one of the core habits that made them so interesting in the first place.

Similar to a gym routine, it must be built right into your schedule and must become an unthinking custom.

If you’re just starting out, focus on building habit first. In Atomic Habits, James Clear writes, “If you show up at the gym 5 days in a row—even for 2 minutes—you’re casting votes for your new identity. You’re not worried about getting in shape. You’re focused on becoming the type of person who doesn’t miss workouts.”

The same goes for reading. In the beginning, don’t focus on volume. Don’t focus on trying to read a specific book in a specific amount of time. Focus instead on the concrete and the practical. For example, each day you could schedule a time to sit down and read at least ten pages. If that’s too much, try five. If that’s too much, then start with one page. Then go from there.

In my case, I wake up in the morning and read as I drink coffee. This is how I start the day. I tell myself I’ll read at least 25 pages (it used to be 15 in grad school). Typically, though, once I get started, I’ll read more.

And as I mentioned, I keep books on my Kindle app. When I have a spare minute throughout the day, I read.

Don’t install games on your phone. If you can’t resist the pull of social media, don’t put those apps on your phone.

Or experiment with variants of George Mack’s cocaine phone and kale phone strategy, wherein he carries his “kale phone” most of the time and only allows himself access to his “cocaine phone” at specific points in the day:

• Kale Phone – Full stack serotonin. Only notes, Kindle, Uber, Maps, and emergency number for 2-3 people to call.

• Cocaine Phone – Full stack dopamine. Twitter. Instagram. TikTok. WhatsApp. Anyone can contact.

Relatedly, do not sleep with your phone anywhere in arm’s length of you.

Before bed, I charge my phone on the other side of the room. And I’ll read (usually a biography or memoir) until my eyes get tired and I go to sleep. Sometimes this period of reading gets me through 2 pages, sometimes 20 or more.

What about money?

For me, books are similar to food. A necessity. Even when I was broke, I still bought books and still read a lot. When I was a kid, before I started making my own money, I regularly visited the school library and the local library. My teachers were sometimes confounded by me because I never did homework and generally earned poor grades but would understand references they made to books they hadn’t assigned to class.

Nowadays, if I see a book that interests me, I always just buy it. The upside of interesting and useful new information vastly outweighs the downside of being out $20 or $30 dollars. Sometimes I buy books and they turn out to be uninteresting or fail to hold my attention. I place it in a pile. Every couple of months, once the stack reaches around 6-10 books, I’ll then donate them to a local used book seller. He allows me to trade them for 1 or 2 used books from the store.

If I couldn’t afford books, I’d spend much more time at the library. I’d download them from libgen. I’d physically steal them if I had to.

I don’t finish every book I start. I skim. I’ll read a chunk of a book, place it on my shelf, and then pick it up two years later and continue. There have been a couple of occasions where I’d read the first page of a book, found it dull, and donated it. More than a year later, I bought it again, and read the whole thing in a few days. Sometimes, you have to be ready for a book.

Most of what you read won’t be especially interesting or insightful. You have to crush a lot of rock to get to the gems. Deep learning demands effort. If you want to possess a large mental universe of knowledge from which to draw, you have to consume a lot of information. This requires focused reading.

I’ll close with this excellent line from James Clear, who said to Tim Ferriss (on a podcast I greatly enjoyed):

“Almost every idea that you have is downstream from what you consume. When you choose who to follow on Twitter, what book to read, what podcast to listen to, you’re choosing your future thoughts.”

To receive new posts, access more than 100 archived premium posts, and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.