Patterns of Legacy Displacement

We have spent most of the last couple of decades helping large

organizations overhaul their legacy systems. In doing this we’ve learned a

great deal about what works and seen many paths that lead to failure. We’ve

decided to set aside some time to writing down what we’ve learned in the form

of various patterns that we’ve seen used.

This article acts as the hub for these patterns. Too often we’ve seen

organizations stuck on a treadmill of half-done legacy replacement efforts. We

think the key to breaking this cycle requires four activities done somewhat in

sequence but mostly iteratively over a company’s life. We use these activities

as our primary structure for organising the patterns that we describe.

We’ve always believed that effective software development involves gradual

release of valuable features, and we think the same is true of writing –

especially in the age of the

web. We’ve started with this narrative article and will gradually

add patterns as we write up their details, as well as other examples that show

how they combine. We can’t promise any dates, since our priority is our client

work, which is not short of legacies to displace. If you are interested in

hearing about more parts of this work as they appear, they will be announced

on Martin’s twitter feed,

and this site’s RSS

feed.

The Legacy Replacement Treadmill

We have worked with many organizations who have made multiple attempts at

removing legacy systems. In one fairly typical organization

they had been through a whole series

of 3-5 year long modernization programmes. Each time they would define a new

tech approach, and then work towards that new approach as part of a large

multi year modernization programme.

At some point during each programme they hit a crisis point where changing

business needs would overtake their current tech strategy and hence trigger

the need to start over. Where they had taken a waterfall “big bang” approach to the

programme this meant abandoning the majority of the work. In other cases

with more incremental delivery approaches, the approach taken was to just add a

layer of slightly newer technologies on top of an already complex

landscape. For both scenarios they were unable to decommission any of their

legacy stack, key business goals for cost savings and risk reduction remained

unmet, an all too common outcome for many legacy replacement efforts.

Several key factors were in play in their repeated failures.

Firstly the poor outcomes they were seeing were largely a product of

the organization; specifically it’s leadership, structure and ways of working.

They thought by just selecting newer technologies, but leaving everything

else more or less unchanged, that they would get different outcomes from the

past. In hindsight this was clearly unrealistic.

Secondly the modernization was to be delivered by a large change programme,

itself comprising a series of projects and teams. These projects were treated

as orthogonal to any BAU (Business As-Usual) efforts. So BAU delivery of business requirements

continued against the existing systems while the new project teams delivered

against a set of requirements agreed at the beginning of the replacement

programme.

Over time they saw a widening gap between what the business actually

needed and what was actually signed off at the start of the programme. The longer each

programme ran for, the more acute this gap between the programme plan

vs. BAU and future needs. While change control processes were

in place to add new requirements to a programme, these were hugely

time-consuming and, due to upfront supplier contracts, prohibitively expensive.

A third key factor in several of the failures was the desire for

Feature Parity with the existing set of systems and business processes.

These attempts began by promising to give the business exactly what they

had today with somehow, behind the covers, the technology having been

“improved”. Having by then seen multiple failures and being concerned about

disruption, the business leaders felt this was a lower risk strategy.

The challenge here was even defining and agreeing current “as is”

functionality was a huge effort and it led to a plan for a large single

“big bang” cut-over release.

Our observations from this and many other organizations is that

technology is at most only 50% of the legacy problem, ways of working,

organization structure and leadership are just as important to

success.

Breaking the cycle

Clearly there is a need to break out of the cycle of “technology replacement

programmes”. In short organizations need to be able to continue to deliver

business needs while at the same time replacing outdated technology, all

against a background of accelerating technological change and a tougher

competitive climate.

There are a series of approaches we have found can help with these challenges.

They aid with the challenge of breaking the problem into smaller parts to

allow delivery of new requirements in parallel with improved technology.

Broadly speaking they fit into four categories:

- Understand the outcomes you want to achieve

- Decide how to break the problem up into smaller parts

- Successfully deliver the parts

- Change the organization to allow this to happen on an ongoing basis

Understand the outcomes you want to achieve

It is vital for an organization to agree the outcomes they want to

achieve when tackling legacy. While this may seem obvious, all too often

different parts of an organization can have quite different views on the

desired outcomes. Most legacy modernization initiatives involve several of

the outcomes we list below, but it’s essential to identify which ones are

the priority before setting out on the journey.

Reducing the cost of change

A key tipping point in many organizations in deciding to tackle legacy is

that desired business changes start to cost far more than any anticipated

benefits, either due to opportunity cost (aka delay) or implementation cost.

An early warning sign is having to spend weeks and 10’s or 100’s of thousands

to make a change to a website that brings only a small increase in business

performance.

At this point it is often no longer possible to justify making

any changes that don’t deliver large returns on investment. In other

words the state of the technology has started to dictate the size of change

the business can make. For many organizations this means the difference

between making a ‘BAU’ change or having to instigate a larger project.

These larger projects then become magnets for all the small changes

that weren’t previously justifiable thus increasing their scope, cost

and risk

Improving the business process

We have seen lots of examples of where business processes have evolved

next to legacy systems, the processes become tightly coupled to the

way that system works with constraints in the system and often workarounds “off system”

shaping the business processes people follow to do their jobs.

One example we saw is an airline check-in system that used “green screen”

terminals, due to constraints in the legacy system the process had to

be followed in a strict order meaning corrections or mistakes meant

starting the check-in process over. Also originally the airline had

not offered connecting flights, when this was added it had to be done

as a separate workflow in the legacy system due to constraints in that

technology. So if, at check-in, a passenger did not mention

they had a connecting flight the wrong process was followed

including printing the wrong baggage tags, only after this would the

system flag the connecting flight. The jobs of the check-in staff and

the passenger’s experience could have been much improved by changing

the process, but this was impossible due to the legacy system.

Given this it should be no surprise that to update and change business

processes in turn requires changes to the how the supporting technology works.

Trying to change working processes without altering the technology often

results in “off system” working where people resort to extracting data

into spreadsheets or similar, working on it there, before importing the

data back into the legacy system.

In one organization the whole stock ordering process was actually done

on a Microsoft Access DB running on the team managers PC. They had

become frustrated as the legacy system could not support the

newer working practices of their suppliers. They would do an import

and export of the data a few times per week, in the meantime the rest

of the organization would see out of date figures as no one realized

what was going on.

It is worth noting here that requirements for a replacement system to

support import and export of data can often have a root cause in this

kind of workaround.

Retire an old system

The need to retire an old system is a common reason for legacy modernization.

This is often driven by challenges in supporting older hardware or software,

with issues such as escalating support costs and reaching end-of-life

on support contracts for both hardware and software.

We’ve found it useful to view the retirement of old systems through the lens of

the business. So a system being built on old technology is not in of itself

sufficient reason for replacement. Instead we need to look at the business

impact this creates such escalating run costs or the risk created by lack of

support or knowledge of the system.

While some organizations do plan well for obsolescence of older technologies,

many seem to ignore the issue until it reaches crisis point. In turn, this

tends to drive organizations towards modernization approaches that seem like

low disruption options or quick wins, these are usually anti-patterns

and we describe some of these pitfalls later.

We’ve been shocked over the years at how many large organizations are

running their businesses on unsupported hardware and software, buying

spare parts on eBay is surprisingly common story to hear. If you have

legacy tech it is well worth doing a proper survey and creating a calendar

featuring the various end-of-life support dates.

While many organizations give retirement of old systems as a key outcome

for legacy modernization it is not uncommon to find this doesn’t actually

happen, the legacy is still being used at the end with the associated

business goals remaining unmet.

Imminent Disruption

For some organizations the actual tipping point on tackling legacy can

arise due to an external factor such as a regulatory change, a new “start up”

competitor or a significant change by an existing competitor. It’s often

at this point when faced with a “must do” change it becomes clear the money

and the time required to respond has grown too large.

The external event is the thing that makes clear to an organization’s

leadership that they no longer have the ability to make changes for a

Proportionate Cost.

Newer technology

Adoption of newer technology should not be the reason for legacy

modernization, just having newer tech for it’s own sake is rarely a

key goal for any organization. Rather it should be selected and chosen in

ways that best meet the current and future needs of the business. A challenge

here is that pace of technological change is accelerating, the “useful”

lifetime of technology is getting shorter. The actual definition

of “useful” depends on the organization, but in general we need to

consider things such as:

- Allows a competitive advantage

- Match competitor or market offerings

- Allows a Faster pace of change

- Cheaper to change

- Has a lower run cost

The choices we make today about the best and most useful technology will

likely be overtaken by better alternatives in a relatively short timeframe.

This makes getting the decision right on finding technology to meet future

needs potentially very risky.

A good approach here is to not make any choices that cannot easily be

“done over” with 2-3 years. This has implications for both technology

selection but also for overall design and approach. Selecting a huge

platform with a 5-10 years pay back time is hard to justify when we

acknowledge this accelerating pace of change.

Decide how to break the problem into smaller parts

Broadly speaking this involves finding the right “seams” in the current

business and technical architecture. Importantly, you have to consider how

elements of the current solution map to different business capabilities. For

legacy systems this usually means discovering how one large technical

solution meets multiple business needs and then seeing if it is possible

to extract individual needs for independent delivery using a new solution. Ideally these

should be deliverable with minimal dependencies on each other.

A common objection is that finding these seams is too difficult. While we

agree it is challenging at first, we have found it to be a better approach than

the alternatives which all too often result in Feature Parity and Big Bang releases.

We’ve also observed that many organizations rule out such an approach because

they are looking at the technology, or the business processes, in isolation.

Changing just one part of the technology, or updating just one business

process independently is likely to fail, but if we can consider and then

implement the two together there are ways to “eat the elephant”.

Getting Started

Legacy modernization can seem a most daunting proposition at the start of the journey. Like any journey, we

must first try and understand the initial direction to take. Also, like all journeys, you must start from

where you are. One common problem we encounter is that we often seem to start in a forest with no view of the

landscape ahead and therefore no idea of the direction to take. The first step, then, is to climb a tree and

take a good look around! This means getting as good an understanding of the current systems and architecture

as possible in the shortest amount of time. This is often super hard to do and it’s easy to get bogged down in

too much detail.

Fortunately there are a number of really useful tools that can be used collaboratively

to get a good enough understanding to proceed. These tools are discussed

in detail elsewhere but a summary list would include

Event Storming,

Wardley Mapping,

Business Capability Mapping and Domain Mapping.

Notice in this list that we are primarily looking at how business concepts

are mapping into the systems architecture, and in turn understanding

how that

architecture supports value generation.

This is a view that is often missing especially for legacy systems.

Create Town Plan †Identify stable parts of the organisation to structure teams and software around

Event Storming †Technique used to understand business processes

Identify Business Capabilities †Identify stable parts of the organisation to structure teams and software around

Value Stream Map †Artefact that describes how users accomplish their work

† currently only a stub

Specifically we find people often stop discovery style activities at the

boundaries of the legacy systems, “here be dragons”, go no further.

Without crossing the boundary and uncovering how legacy systems support

(or hinder) business process and activities it is challenging to find

and extract thin slices to deliver.

Another oft overlooked and very valuable source of information are the users of the systems themselves. In

fact, in the authors experience this is often where you can find the surprising amounts of useful stuff and

especially expose the many workarounds and shadow IT ecosystem that usually builds up around older systems –

that is, the Access Databases and versioned Excel Spreadsheets that actually run the business. Customer

Journey Mapping, creating Service Blueprints and Value Stream Mapping are tools that have been used to good effect

to surface this kind of detail.

Extract Product LinesIdentify and separate systems by product line.

Extract Value Streams †Identify and separate key value streams

Feature Parity

Replicate existing functionality of a legacy system using a new technology stack.

† currently only a stub

Successfully deliver the parts

The need for faster change and the ability to incrementally deliver and

independently change elements of the business without large dependencies often

leads to “agile” delivery approaches alongside a microservices based architecture.

Continuous Delivery becomes a must have for these individually deployable components.

What makes this challenging beyond just a normal piece of software delivery is finding

strategies for cut over from, co-existence with and, ultimately replacement of

elements of an existing large solution. Several successful strategies exist

including parallel run, fork on ingress and diversion of flow.

Canary Release †Roll out a change to a subset of users

Critical AggregatorCombine data from different parts of the business to support

making critical decisions

Dark Launching †Call a new back end feature without using results in order to assess

its performance impact.

Divert the FlowFirst divert cross-organization activities away from legacy

Event InterceptionIntercept any updates to system state and route some of them to a new

component

Legacy MimicNew system interacts with legacy system in such a way that the old system

is not aware of any changes.

Revert to SourceIdentify the originating source of data and integrate to that

Stop the World cutover †Suspend normal business activities while cutting over to new system

Transitional ArchitectureSoftware elements installed to ease the displacement of a legacy system that we intend to remove when the

displacement is complete.

† currently only a stub

Change the organization to allow this to happen on an ongoing basis

If we step back and look at the whole process of delivering new business

requirements we can quickly see this is only partly a technology problem. If

we use newer technology to cut time and cost of building solutions we will

then highlight any issues around agreeing requirements and getting the change

into production.

We need organization structure and process changes to take

full advantage of the better technology, and by Conway’s Law we

also need an architecture for our technology that facilitates this. If

teams and their communications are organized around the existing legacy

solution and processes we may need to reorganize them using the

Inverse Conway Maneuver to match the new

solution and it’s architecture.

Legacy systems can constrain and limit the ability to adopt more

modern engineering practices especially those associated with eXtreme

Programming and Continuous Delivery. When replacing legacy systems it

is important to make sure ways of working are changed to ensure we

don’t end up back with a system that is slow, difficult and expensive

to change.

Legacy is also the product of an organizations

culture and leadership, without broader change you should expect the

same outcomes as seen previously.

We have observed many legacy modernization efforts fail due to

“corporate antibodies” which spot something new happening and act to

reject it from the organization.

To give just one example of the way a broad organization can reject

change; we worked with a very large telecommunications company who wanted

to build software for mobile phones. The leadership all understood this

meant much faster feedback cycles and more frequent changes than they

saw with existing programmes which were focused on fixed infrastructure.

While the leadership understood this no changes were made to existing

working practice or to the middle management who ran those processes. So

existing change control processes were rigorously applied. In the end

the software teams were spending more time filling in change control

forms and attending change control meetings than they were producing

software. The “corporate antibodies” worked successfully to reject the

new way of working.

Organizational change is a big topic with much literature already available,

the key challenge with legacy is often time related. Few organizations can

afford to delay legacy modernization while they rework (or rebuild, for

outsourcing victims) their whole delivery approach along side their

organization structure and key business processes. While the broader topic

of organization transformation is beyond our scope we do recommend some

strategies for applying and protecting new ways of working in the context of

legacy. If you just change the legacy and do nothing else it is fair to

expect you’ll replacing legacy again with a few years.

Build as you mean to continue †Create your legacy replacement in the way you need to continue once it is live.

Incremental Displacement †Create your legacy replacement in the way you need to continue once it is live.

New Co †Form a brand new company to pursue a market disruption

Protected Pilot †Create a pilot program for new work and detach it from the normal

corporate governance process

† currently only a stub

There are definitely other strategies and approaches to organization

transformation, we just highlighted these two as to some degree they

allow work to be started on the legacy modernization sooner rather than

later.

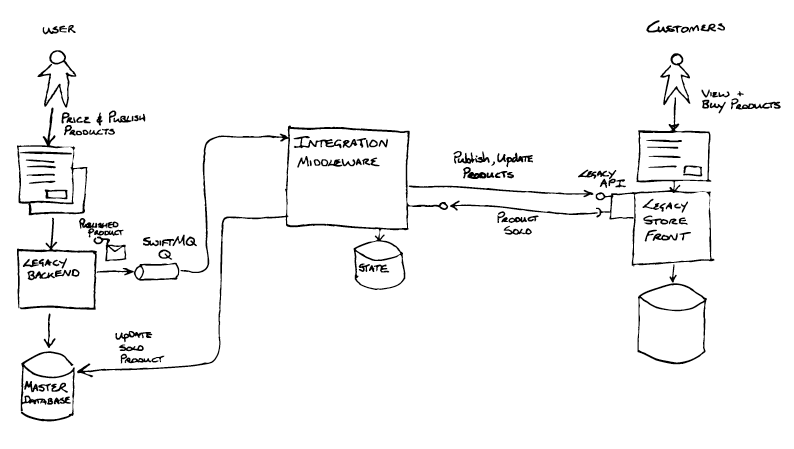

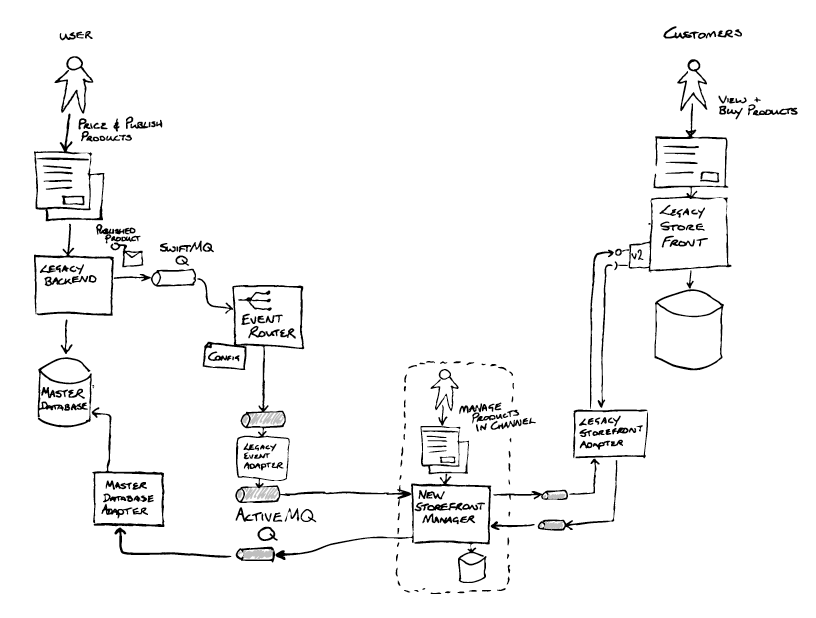

An example: Integration Middleware Removal

This example describes how one of our teams used a number of Legacy

Modernization Patterns to successfully replace integration middleware

critical to the operation of their client’s business as part of a larger

legacy modernization programme. They combined patterns and refactorings to

successfully manage risk to the business, and facilitate eating this

particularly gristly part of the elephant.

Understanding the outcomes

The challenge faced by our team was how to replace integration middleware

that was out of support, hard to change and very costly with a new

supportable, flexible solution for the business. Without disrupting or

putting at risk existing business operations. The middleware in question was

used to integrate between a backend end system and a store front. Together

these systems were responsible for selling high value unique products worth

tens of millions of pounds every day.

This work was a high priority part of a larger programme. The entirety of

the backend systems supporting the business were being replaced, and the

store front was also going to be subject to a modernization programme within

a couple of years.

So, as per step 1 above, the business outcomes the team needed to achieve were defined:

- Improve the business process

- Retire old system as soon as possible

How? This particular integration middleware solution contained a significant amount of logic including rules

core to the business, like which channel to sell a product on, or how and when to present a product for sale

within the store front. This existing system was very hard to change, stifling business innovation, and flaws

in the logic resulted in issues like having periods when a product was not even on sale!

Why? To reduce existing (and increasing) license and support costs. Additionally, to mitigate the risk to

the business created by operating critical functions on aged out of support middleware and database

technologies.

Breaking the problem up: the first seam and a refactoring

During Inception the team ran a workshop

with people who had deep knowledge of the legacy system, to collaboratively

visualise both the as-is and to-be software architectures.

Having done this, they found a technical seam that could be exploited in

the form of messaging based integration between the legacy backend and the Integration

Middleware. The Legacy backend, an aging J2EE application, placed “publish product” messages

onto a queue provided by a very old version of SwiftMQ. The Event Interception pattern would be useful here,

and if implemented as a Content-Based Router

would allow control over how messages from the legacy backend were routed,

and create an option enabling messages to be routed to new systems.

The integration middleware also handled messages coming from the Store

Front (e.g. for product sales), using JDBC to directly update state in the

Master Database behind the legacy backend. Together the asynchronous

messaging via SwiftMQ and the JDBC database updates formed the interface

between the Legacy Backend and the Integration Middleware.

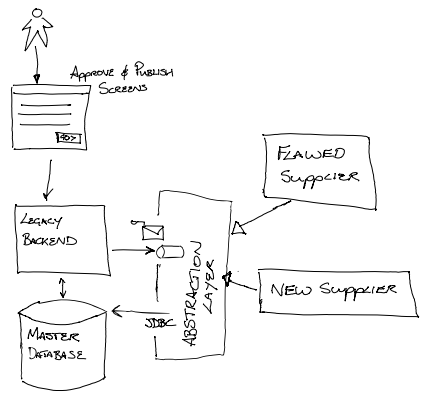

Although, not spotted at the time, the team were able to use the Branch by Abstraction pattern, at a sub-system scale, as

the strategy to enable the replacement of the legacy middleware. The

abstraction layer being the queues and the JDBC. By ensuring that the new

implementation adhered to that abstraction layer it could be swapped for the

“flawed supplier” without impacting the business operations.

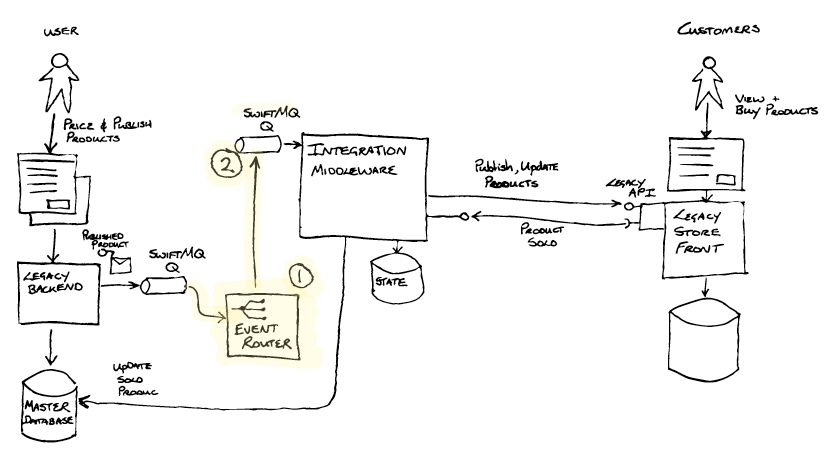

The first thing the team did was to implement event interception by

adding an Event Router via a refactoring.

The Event Router (1) was created with three main capabilities in

mind:

- To de-queue messages from one SwiftMQ queue and en-queue them onto

another SwiftMQ queue (2). A trivial change of some config enabled the

Integration Middleware to consume messages from this new queue(2). - The vision for the Event Router was to enable, through configuration,

routing of messages to an alternative destination – enabling the new

implementation to process the publish messages. Event Interception - The Event Router would also provide a bridge from the old SwiftMQ

technology to the new ActiveMQ technology chosen for the target

architecture.

Overall the refactoring left the observable system behaviour unchanged,

but the Event Router was now part of the Transitional Architecture,

having been inserted into the message processing pipeline.

Implementing the Event router was not as straight forward as it could

have been. Integrating with SwiftMQ was problematic due to lack of available

drivers / libraries and the approach was challenged a number of times. The

team understood the value of the options that this approach would unlock,

and completed the work and released into production. They monitored the new

component in the wild and were set to incrementally enhance its capability

using new Continuous Delivery pipelines.

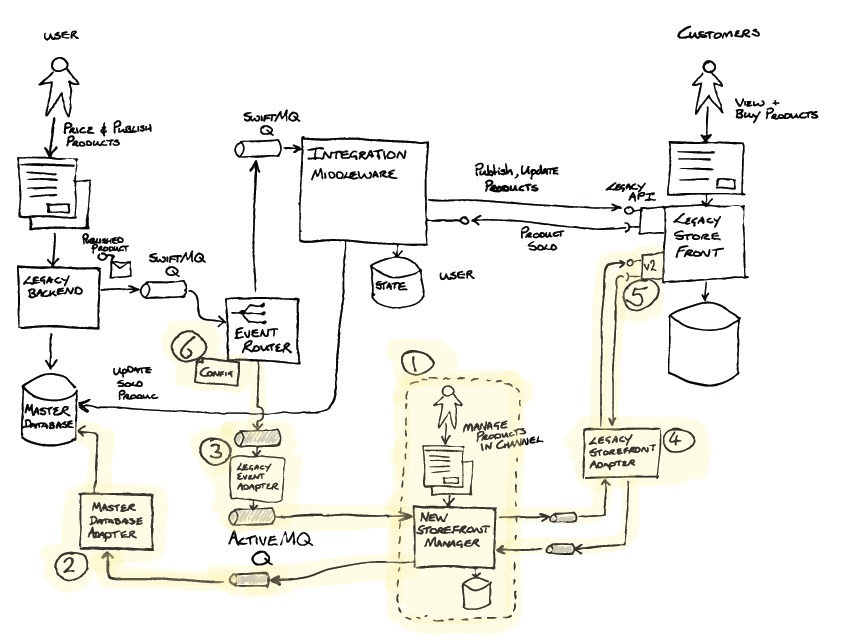

Successfully deliver the parts: building out the functionality, maintaining the contract

The new Store Front Manager(1) was now iteratively built out by the team

. Relevant to this example, that build included the Master Database

Adapter (2) implementing the Legacy Mimic pattern. This was required as part

of the abstraction layer, to update the Master Database with sales

information received from the Store Front. As the Event Router did not

transform messages, a Legacy Event Adapter (3) (Message Translator) was created to transform messages

into a new format, not exposing the legacy world to the new, and aligning to

the principles of the new architecture. The Legacy Storefront Adapter(4) was also implemented between the new Store

Front Manager(1) and the Legacy Store Front to isolate the new

implementation from future changes that would be coming when the store front

was replaced.

A new API was introduced on the Legacy Store Front (5) that the new Store

Front Manager was to use. Additionally, a feature was added enabling call

backs for products published on the new API to be sent to the new Store

Front Manager’s adapter (4). Critically, this enabled the legacy

implementation and the new implementation to be run in parallel.

Successfully deliver the parts (cont.): transitioning into live service – using a second seam

With all of the pieces in place the business were able to test the new

solution, but how to roll it out into live service in a risk managed way.

To do this they took advantage of another seam – this time using the

Segment by Product pattern. The Event Router was enhanced to add

configurable routing (6) by product type as well as by unique

product IDs. The team were able to test the publishing, management and sale

of individual products by ID, and then over time configure the router with

progressively more and more product types, essentially increasing the

percentage of products handled by the new solution.

When all products were being handled by the new systems, the legacy

Integration Middleware was decommissioned, realising the significant £

saving in license, support and datacenter hosting fees.

Changing the organisation to allow this to happen on an ongoing basis

Our teams had already been working with the client, in another part of the organisation and had already

successfully displaced a different legacy system.

At an engineering level across the organisation continuous delivery and good supporting quality practices

were now the established norm, and a microservices style architecture enabled regular and independent deployment

of containerised services onto a cloud based platform.

The teams on the new programme, working with new stakeholders, needed to take this other part of the business

on the same “agile and CD” journey, and early risk managed releases enabled trust to be earned. Over time it

was possible to demonstrate how new engineering and quality practices including CD were mitigating the same

risks that had historically resulted in higher levels of bureaucracy and governance. So less frequent,

larger scope releases were also displaced by smaller, more frequent, higher confidence deployments, and

toggled releases to the business when they were ready to take on the changes.

Closing thoughts

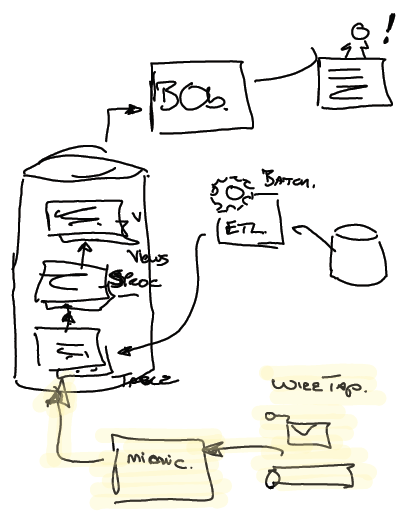

Of course there was significantly more complexity and

integration requirements than implied by the simplified story above. An example

of the need for Archeology introduced itself shortly after testing the

new implementation in production. A number of business critical management

information reports did not tally – products were “getting lost”.

After much digging the team found that the database used by the

Integration Middleware (for storing the state of long running business

transactions) was replicated to the organisation’s data warehouse. Via a number

batch jobs, stored procedures and views this data was made available for use

within the business critical KPI reports.

Additional Legacy mimics were required to ensure that these reports

did not break. The team used a

Wire Tap on

sales messages coming from the Store Front and using JDBC injected the data into

appropriate tables within the data warehouse. These additional mimics

also became part of the transitional architecture, and would be removed when

possible.

The approach of branch by abstraction, and use of patterns and practices

described above was one intended to lower risk.

Using Event Interception (technical seam), Legacy Mimics and Transitional Architecture

enabled the client to break the problem up. Then segmenting by product (business seam),

in this case product type, enabled fine control of the wider rollout and further management of risk.

Overall the approach allowed the business to proceed with the system replacement at the pace that was

comfortable to them.

The approach allowed risk to be managed, but came at a cost. A question to consider is therefore

“What value does the business place on this risk mitigation?” Being explicit and quantifying it, will allow

a team to track investments against it.

The event router and legacy mimics were part of an investment in a transitional architecture intended to manage

risk. Their roles were to create options enabling risk to be managed. It can be very easy for such work to be

seen as “throw away” – and as such a cost to be avoided wherever possible. Be explicit and transparent in this

“value of risk mitigation” vs “cost of transitional architecture” trade-off.