Table of Contents

Some of you know that I work in the agency business — how that translates to my technical experience is that I used to work on many highly different projects over the years — in contrast to a product-based company where you work on a single product, your whole career. As one of my friends, an agency owner, said: “A year in the agency equals three years in the product company.” You can agree or disagree with that statement, but my life is filled with many different projects on a daily basis from various domains with different vendors and clients.

As you might guess, over time, this experience accumulates into a unique perspective on why projects fail — regardless of the industry, who’s leading the initiative, and who the stakeholders are. Sometimes, projects fail, and you can’t point to a specific thing that went wrong.

My experience, though highly subjective, suggests that even well-planned, well-funded projects tend to fail. I’ve been part of projects, even the ones that seem to have everything going for them, and there was always a chance they’d hit an iceberg. You’ve got deadlines, budget constraints, people falling out, new stakeholders getting onboarded, and all that jazz. Those are the apparent reasons the project can get derailed; they lay on the surface and are easy to spot.

But the silent killers? Those are the ones that creep up on you — the subtle issues that aren’t immediately obvious but can seriously mess up your timing if you’re not careful.

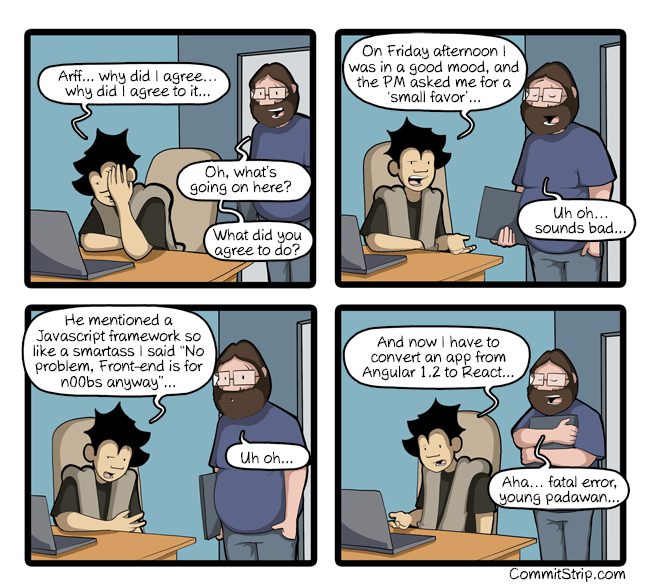

Source: commitstrip.com

Why software projects fail is not a new topic, nor is this article groundbreaking. Over the last week, I’ve read a dozen white papers about failed software projects and tried to combine them with my experience. This essay is the result of this combination — I will not focus on things already discussed by many. I will try to show you the not-so-obvious reasons why projects fail.

Overconfident developers

Confidence is cool; overconfidence, not so much. One of the things that I’ve noticed is that developers often underestimate not just the complexity of tasks, but there’s a general overconfidence in their abilities, not limited by programming:

- Overconfidence in their coding skills.

- Overconfidence in learning new technologies.

- Overconfidence in our abstractions.

- Overconfidence in external dependencies, e.g., third-party services or some open-source library.

If you ask a developer if they’ve ever written bad code, they will most likely say no. I’m guilty of this as well. I don’t remember ever writing bad code; sure, some of it wasn’t perfect and could be improved, but I don’t think it was terrible, per se. Nonetheless, if we asked everyone who reviewed my PRs if I ever wrote bad code, the answer would be yes; some of the code was probably garbage.

On average, I write decent code; on average, I can solve a task quite quickly; on average, I can build the module on time.

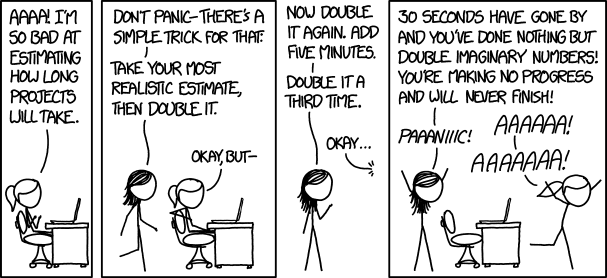

If you ask me If I can build some feature in three weeks — after analyzing the requirements, I will tell you with confidence, based on my average past performance, that I’ve built similar things in the past and am pretty sure I can do it again. But there are always outliers, and we neglect them during estimations. We, as software developers, are guilty of overconfidence, leading to failing software projects.

💡 There’s also this concept called The Planning Fallacy, a term coined by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, which describes our tendency to be overly optimistic about our capacity to complete tasks quickly.

Another great example of overconfidence are bad abstractions. Unless you live in a perfect world, you probably know that duplication is better than bad abstractions. The problem with that statement is that you always assume that your abstraction is better — you’re not a junior dev, you’re confident in your skills (overconfident one might say) you know what you’re doing, you want to make everything neat and tidy and you’ve done this a dozen of times. The code looks perfect and will probably pass the code review.

After some time, new requirements pop up, almost fitting the existing abstraction, but not quite — someone tweaks the abstraction, adds a parameter, adds some condition, adds some switch statements. Repeat this several times, and you have a piece of code that’s so complex that nobody wants to touch it. Everyone continues using the overblown abstraction because they think this piece of code was written by someone smarter than them — and the cycle continues until someone brave enough confronts the complexity and starts adding duplication again to untangle the code.

The problem with bad abstractions is that their effect on the project timeline is like a snowball. At the start of the project, any feature that is related to that abstraction is done on time and doesn’t raise any red flags, but as the project goes on longer and longer, the time to modify the abstraction increases exponentially until it hits the point where the abstraction becomes unmaintainable and impossible to extend. Delays start piling up, until the project comes to a halt.

There’s an even better example of overconfidence — the learning curve of new technologies. If you’ve been coding in Golang and the project will be done in Rust, how much effort will you need to become proficient in the language? Developers often jump onto new technologies without fully appreciating the time and effort required to master them. This underestimation leads to delays as the steep learning curve is not sufficiently accounted for in project timelines or risk assessments. And if we dive even more deeply — new technologies always have a risk that the framework/language/driver/adapter has limitations that your team has not yet seen or knows about, which will result in figuring out workarounds to make things happen.

The need for workarounds is even more true when dealing with external dependencies and third-party vendors — anything you do not directly control is a risk of hidden complexity. The assumption that third-party services, libraries, packages, or APIs will work as expected without bugs is a common oversight. Unless you’re building simple CRUD applications, projects often get derailed when these external dependencies get deprecated, become incompatible with other dependencies, or plainly stop providing the service.

It’s hard to plan for that. We’re overconfident because, on average, it works out, except when it doesn’t. If we try to quantify this and multiply this probability by the number of developers on a project, even the best projects, if they get big enough, have a hundred percent chance to either go over the budget or deliver too late.

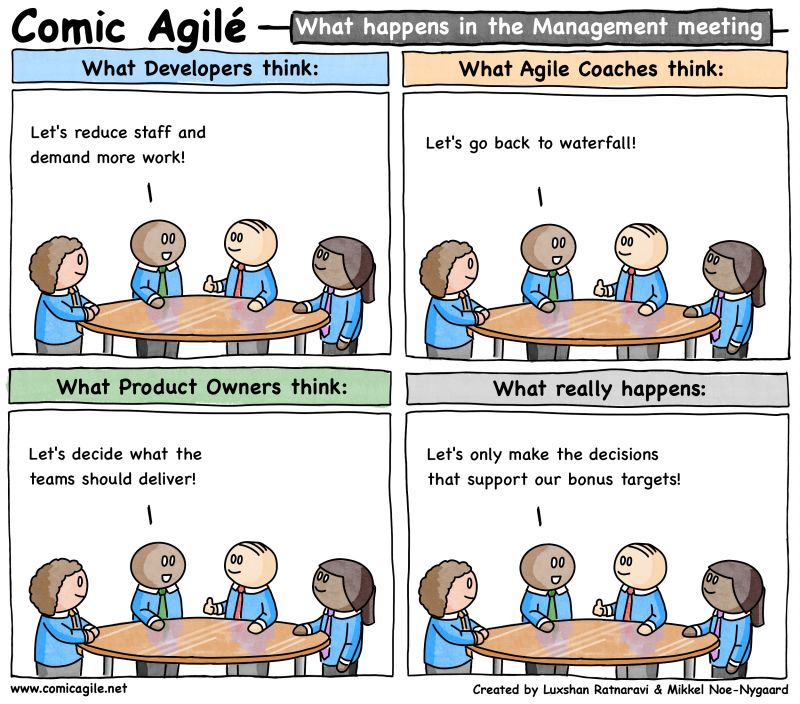

Inexperienced Managers

So, what’s the next thing that you can’t plan for? You guessed it: inexperience and/or incompetence and/or negligence. I’m using these interchangeably, as you never know where one ends and the other starts. There’s a massive mismatch between what makes a manager successful in the eyes of their superiors versus what truly benefits a project and its team.

On one side of the spectrum is a manager with their own ambitions in mind rather than the project’s success. A good example is promotion-based development, where managers leave projects before they are completed, leveraging their position for a career boost. Peter Principle says that people get promoted to their highest level of incompetence. It’s not that these managers are inherently bad at their jobs; it’s just that what got them the promotion isn’t what’s needed to lead the project to success — it’s a different skill set.

On the other side, we have managers without enough experience who a) assume someone else will do the job and b) assume that their job is to satisfy all the stakeholders and say yes to everything. They overlook the necessity of robust and firm planning, allowing process debt and scope creep to derail projects.

If you see these red flags, you should be ringing alarm bells:

- Information from upper management is not shared, leaving the team in the dark about broader project developments. I call it, “Trust me, we’re moving in the right direction.”

- Tasks are assigned without context, necessary resources, or contacts, only mentioning deadlines. I call these “figure-it-out-yourself” tasks.

- They will often turn the team’s work in as if they’re responsible for the whole thing, getting praise from the upper management but not sharing it with the team.

- Always afraid of taking on responsibility, never makes decisions independently, always defers them to upper management… which only they are allowed to talk with.

- Blames the team for mistakes in front of the upper management.

These are just some of the characteristics of an inexperienced manager; if you have more.

The biggest mistake an inexperienced manager can make is allowing frequent changes to the project’s scope, especially those imposed by higher-ups, without proper consideration of the implications. For example, “The CEO said his daughter thinks we should have Login with TikTok on our banking app, and I think this is a great idea!” This leads to many sighs in the team, resource strain, and shifting priorities, resulting in project failure.

Mismanaged Stakeholders

A project’s true north should always be its value — real, tangible, and aligned with the business goals it seeks to fulfill. Nobody would want to build a project that’s just a drain on the resources, right? Of course not, but the problem is you never really know if your project has turned into a zombie until it’s too late.

Our minds play tricks on us – confirmation bias makes us blind to the signs that the project is going in the wrong direction, and the affect heuristic leads us to downplay the bad and inflate the good, especially when we’re emotionally invested in the project’s success.

These projects always start with a promise – a clear goal, a vision aligning with the company’s strategy, reasonable financial forecasts, and a decent development timeline. It feels like a great opportunity; it’s hard to notice anything wrong during the initial 30-40% of the project.

But then things start to change, and unexpected challenges arise.

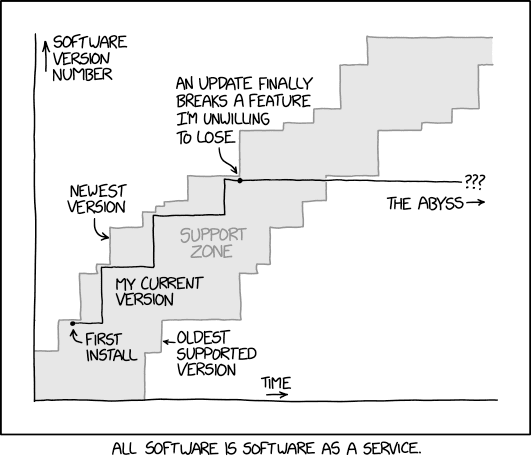

Technology that seemed straightforward refuses to cooperate, external competitors launch similar ideas, key partners back out, and internal business stakeholders focus more on the projects that include AI in their name. Things slow down, and as months turn into years, enthusiasm wanes.

Then the snowball continues — key members leave, and new people join, each departure a slight shift in direction. New tech lead steps in, eager to leave their mark, steering the project further from its original course. At this point, nobody knows where the project is headed, and nobody wants to admit the project has failed. It’s a tough spot, especially when everyone’s playing it safe, avoiding the embarrassment or penalties of admitting failure.

💡 The silent killer in this scenario isn't just the project's failure to deliver value; it's the collective reluctance to acknowledge that failure. Fear of admitting defeat, of facing the repercussions of a project gone south, keeps the team from developing the product further.

Why? Well, it’s awkward, isn’t it? Admitting defeat means facing some uncomfortable truths. And nobody wants to be the bearer of bad news; nobody wants their name attached to “that project” that failed, so they keep the project alive, using creative budgeting, overpromising, and forever pushing success just out of reach, hoping for a miracle or reassignment to some other project.

Deep down, everyone knows the truth, but they will never admit it. This project isn’t going to hit its targets; it’s not getting released, or maybe it will, but the financials won’t be that good. It’s not going to revolutionize the market. It’s just… going to continue consuming resources without really achieving anything.

When such software projects start failing, a negative mindset quickly spreads. Instead of fixing the issues, people say, “Well, that’s not my job.” or “I’m doing my part; everything else is not my concern.” Everyone’s looking out for themselves, trying to avoid the consequences. This attitude stalls any attempt at genuine problem-solving and deepens the project’s issues, making recovery even more challenging.

When a “not my problem” attitude prevails, it becomes the seed for a toxic culture. In such an environment, accountability is dodged, and collaboration dwindles. Team members focus solely on their tasks, ignoring the bigger picture and the collective goal. This lack of shared responsibility leads to blame-shifting when things go awry, creating an atmosphere of distrust. The energy that could have been used for problem-solving gets wasted on internal politics and protecting one’s turf.

Conclusion

Projects fail. It sucks, yes, but it’s the truth. It’s not just about bad coding or missed deadlines. Inexperience, ego, overconfidence. All of these human traits have a huge impact. So let’s try to avoid them and be better role models?

Let me know your stories about failing software projects in the comments.

Other Newsletter Issues:

- Falsehoods Junior Developers believe about becoming Senior

- Database Migrations

- Habits of great software engineers

- Proper Software Development Estimations

Reactions

Hot! The last couple of years I’ve been writing about CTO / Tech lead job. I’ve compiled all my knowledge into a printable PDF. I called it “196 Pages of No Bullshit Guide for CTOs”. So if you’re interested, take a look.

Hot! If you’re a software engineer looking for a job, I started a Roast my Resume service, where I record a personalized video of me “roasting” your CV, which basically means taking a hard look at your resume as a CTO and commenting on all the good and the bad parts.