The Next Big Performance-Booster Is Already in Your Kitchen

Olof Sköld was in a small, hip bike shop in Paris last summer when conversation turned to something odd that people had noticed while watching Tour de France coverage. “Everybody was talking about [Primož] Roglič,” Sköld recalls. “He’s eating soup before racing! There must be some doping in it!” Tour de France riders burn as much as 8,000 calories a day, so they’re famous for hoovering down energy in every available form. But slurping soup before a race was, admittedly, unusual. Sköld, the CEO of Swedish sports nutrition company Maurten, knew exactly what was in the soup, but he wasn’t telling—yet.

Back in 2016, Maurten made a big splash with their new carbohydrate drink, which claimed to ease the pangs of digesting large quantities of sugar during hard exercise by encapsulating it in a hydrogel. Simple carbohydrates are the primary fuel for high-intensity exercise, and top endurance athletes aim to take 60, or 90, or even 120 grams—the equivalent of almost five gels—for every hour of racing. It doesn’t go down easily. “If you went to New York or any of the big marathons back in 2015, they had sand in buckets at the finish line to clean up all the vomit,” Sköld says. “That really doesn’t exist anymore.”

While initial research into Maurten’s carb drink was equivocal, it now appears that the formula really does reduce gastrointestinal distress. The hydrogel, which forms in the stomach when the drink’s ingredients mix with stomach acid, effectively “hides” the carbohydrates from the stomach’s signaling systems until they’ve safely passed into the intestine. Even before the research caught up, word-of-mouth helped the drink spread rapidly among both elite and serious recreational athletes. The company has grown by about 120 percent annually for the last six years, Sköld says. And now they have another hydrogel-based product, launching at the end of February, which they believe will spark a further revolution.

The first indoor track meet of the year is always a shock to the airways. The frantic deep-breathing of the final laps of a race combined with the bone-dry winter air leaves just about everyone with a vicious “track hack.” In January 1995, after struggling through a leg of the 4×800-meter relay at the historic Dartmouth Relays, I staggered to the bleachers and reached blindly for my water bottle. Instead of throat-soothing water, though, I got a foul-tasting concoction that almost made me vomit. I’d accidentally grabbed my teammate’s water bottle—and he, it turned out, was soda loading.

The performance-boosting effects of sodium bicarbonate—that’s baking soda to the cooks and primary-school volcano-makers among us—have been researched for decades, going back at least to a 1984 study by pioneering sports scientist David Costill. The simple story that runners like me heard in the 1990s went as follows: hard exercise generates muscle-fatiguing lactic acid. Baking soda is a base that can counteract the rising acidity in your bloodstream, and thus indirectly counteract the negative effects of lactic acid in your muscles. The lab data showed that it worked, and the explanation made sense. Case closed. “Then researchers left it alone for a while,” says Andy Sparks, an exercise physiologist at Edge Hill University in Britain. “They thought all the work had been done.”

At the time, baking soda’s performance-boosting effects were so widely acknowledged that using it was considered a “restricted technique” by the forerunners of the World Anti-Doping Agency. They couldn’t place an outright ban on baking soda—you can’t take away muffins, after all. But taking large quantities for the express purposes of enhancing performance, as my teammate did, was considered verboten, though the rule was largely symbolic rather than enforceable.

Instead, there was a far more practical limitation on its use: it’s famously volatile in the stomach. At the conference championships that same year, my teammate had to withdraw from the relay because he’d overdone the soda loading for his individual events and was locked in the bathroom with explosive diarrhea. I got the call-up to the A squad, ran a three-second personal best, and earned my first trip to nationals. For that reason, I’ve always credited baking soda for that performance breakthrough—but thanks to the side-effects I was never tempted to try it myself, even after WADA removed any restrictions on its use a few years later.

The modern understanding of muscle fatigue, and of baking soda’s benefits, has evolved since the 1990s. Hard exercise above threshold generates lactate and hydrogen ions. Lactate is actually a valuable fuel, but the rising acidity associated with the hydrogen ions is thought to impair muscle contraction. Baking soda in the bloodstream helps pull these hydrogen ions out of the muscle cells and neutralizes them, thus counteracting fatigue. That’s one theory; there are others relating to potassium ions, or more generally to the role of so-called “strong ions” as a group. The mechanism is still up for debate, but the practical results aren’t. “The majority of studies say yes, it’s ergogenic [performance-enhancing],” Sparks says, “but for some athletes it’s curtailed by the GI problems.”

That’s also the consensus in the sports world. “It works,” says Kevin Sprouse, a sports medicine physician in Knoxville who is the director of sports science for the EF Education-EasyPost Pro Cycling Team. “It absolutely works.” But it’s finicky. Half the riders on a given team might not be able to tolerate it at all. The other half might vary in how much they need and how quickly it enters their system. There have been numerous attempts to find more reliable protocols: split doses, delayed-release capsules, and even a topical gel called PR Lotion. But none has really cracked the problem.

Meanwhile, there are hints that baking soda might have broader benefits than initially thought. Since its primary function is to counter rising levels of acidity, most of the research has focused on short, intense exercise bouts lasting between about one and ten minutes—the type of activity that produces the highest levels of lactate. But one study found improved sprinting even at the end of a three-hour race. And other lines of research suggest that it might accelerate post-exercise recovery by regulating acid-base balance in the blood, and perhaps even augment adaptations to endurance training through a cellular signaling mechanism called PGC-1alpha, says Lewis Gough, a physiologist at Birmingham City University in Britain.

It’s a potential miracle drug, in other words—if you believe the hype, and if you can get rid of the pesky explosive diarrhea. That’s where Maurten comes in. The hydrogel in their carbohydrate drink, after all, is nothing but a delivery system for getting carbs into your bloodstream without upsetting your stomach. “Bicarb was much harder,” Sköld says. “It took several years to get it right.” The formula they settled on involves mixing ingredients to make a yogurt-like (or soup-like, to some observers) slurry, then adding a spoonful of individually encapsulated micropills, each with 0.018 grams of baking soda. Take a total dose of 0.2 to 0.3 grams per kilogram of bodyweight. Slurp it down two to three hours before a race or competition, then go for gold.

Once they’d settled on a formula, they started testing it on elite athletes—and on themselves. In late October, when I spoke to Tobias Christensson, Maurten’s head of nutrition, he was in northern Sweden at a training camp with the Swedish cross-country skiing team. He’d just given them a seminar on the new product: the title was “Used by 1% for the 1%,” meaning that very few athletes currently use baking soda but those that do can expect a one-percent performance bump.

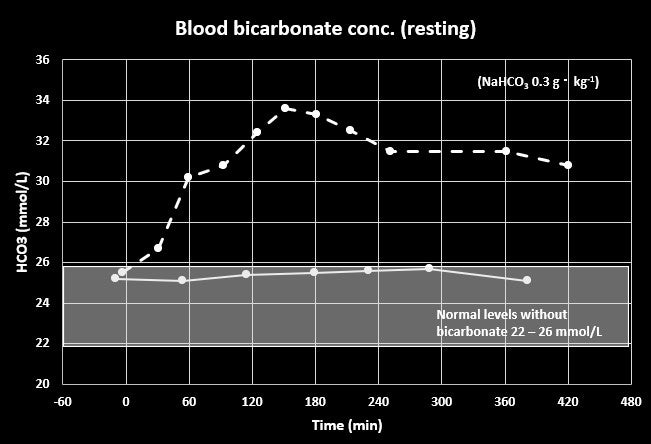

In the seminar, he shared with them the pilot data he’d taken on himself, using an ABL9 blood gas analyzer to measure blood pH and levels of bicarbonate. First he showed them that the formula did, indeed, raise the levels of bicarbonate (HCO3, on the vertical axis) in his blood. Normal soda loading is thought to raise bicarbonate levels for two to three hours. His levels, in contrast, were still elevated after seven hours.

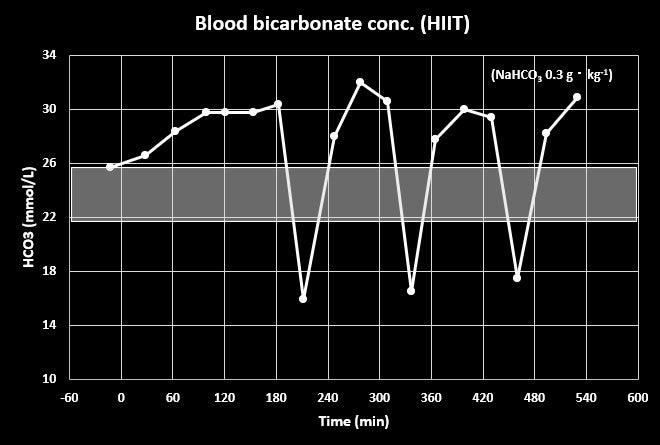

Then he showed them what happened when he exercised. A hard interval workout made bicarbonate levels plunge… but then they surged back up when he stopped. The same thing happened when he did another workout a few hours later. Bicarbonate levels generally stay between about 22 and 26 mmol/L, but the hydrogel dose seemed to be protecting higher levels for many hours. Here’s what his levels looked like when he did three intense interval sessions over the course of five hours, dropping during each workout then rebounding during the recovery:

“After nine hours, I’m still elevated,” Christensson says. “And I could actually replicate this, so of course this pattern was really, really interesting for Jumbo-Visma.” That’s Roglič’s cycling team, and one of Maurten’s key partners. Grand Tour races play out over the course of many hours, largely below threshold but punctuated by intense accelerations up hills, around corners, and to cover breakaways. Most of the team’s riders had at least experimented with baking soda in the past, says Mathieu Heijboer, Jumbo Visma’s head of performance, but some couldn’t stomach it. Maurten’s formula changed that, he says: “Especially riders who experienced gastrointestinal issues with regular bicarb found it a game-changer.”

Christensson has carted his ABL9 blood gas analyzer to endurance training hubs around the world—Font Romeu, Flagstaff, Tenerife—to do bespoke testing with top athletes, who also began trying it in competition. One of the breakout stars of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing was Nils van der Poel, the Swedish speedskater who won both the 5,000 and 10,000 meters in world record times, then posted a lengthy manifesto revealing his training secrets for all to see. Buried halfway through the 62-page document was the revelation that he was using a bicarbonate mix produced by Maurten “which also worked good for my belly.”

One of the practical challenges for van der Poel was that he did many of his sessions first thing in the morning, making it difficult to take baking soda two or three hours beforehand. His solution? “I would take the soup the night before instead,” he says. Even after nine hours of sleep, he still saw a typical boost of 4 watts, or 1 percent, in his bike sessions, consistent with Christensson’s observation that bicarbonate levels stayed elevated for many hours.

When van der Poel skated to gold, Sköld was watching the broadcast proudly from his office alongside Kilian Jornet, the trail running legend. Jornet, too, started experimenting with Maurten’s baking soda more than two years ago. He tested it out in a two-hour ski mountaineering race, and—unlike when he’d previously tried regular bicarb—his stomach felt good. So he tried it in a 100-mile race. “Especially the second time I took it, 12 or 13 hours into the race, my muscles felt less clumsy,” he says. For middle-distance runners, the most noticeable benefit of baking soda is that it reduces the burning feeling of intense exercise, allowing you to push to higher lactate levels. But for trail ultras, Jornet believes the benefits are more neuromuscular, keeping his muscles working smoothly and enabling him to pick his way across rough terrain, up and down steep inclines, even after more than a dozen hours.

Plenty of other notable athletes are using it. Joshua Cheptegei, the Ugandan runner who holds the world records for 5,000 and 10,000 meters, was an early adopter. Tove Alexandersson—“the Eliud Kipchoge of orienteering,” Sköld explains—uses it for races ranging from six- to eight-minute sprints to 100-minute endurance contests, where the up-and-down terrain generates bursts of lactate. “It also feels like the body recovers a bit faster,” she says. “But I haven’t done any tests, it’s just my own feeling.”

The Dutch rowing team, with 35 mostly very large rowers on its squad, has been a big user. “When we switched to Maurten, there was a noticeable difference,” says Koen de Haan, a scientist with the program. “More people could tolerate it.” At the last World Championships, every single woman on the team medaled, and not a single rower reported stomach problems. “I always start with ‘Don’t believe the hype,’” says de Haan. “But it just works.”

Sköld offered to introduce me to a more or less endless list of satisfied users. Alexander Kristoff, the Norwegian Olympic cycling medalist and multi-time Tour de France stage winner, said that he was able to double his tolerable dosage. Another multiple Grand Tour stage winner, who needed to remain anonymous due to sponsor conflicts, raved about the ability to dig deeper and emphasized the possibility of boosting training adaptations. “We believe we’re making the biggest difference in training,” he said. And there were more names, among the very biggest in history in several different endurance sports, that Sköld dangled but forbade me to repeat due, once again, to sponsor conflicts.

At a certain point, further testimonials became meaningless. The athletes clearly like it, just as they liked the original Maurten carbohydrate drink. But what about the evidence? Back in 2016, Maurten’s media liaison, Herman Reuterswärd, contacted me to suggest writing about their then-unknown carbohydrate drink. I was intrigued, especially after Eliud Kipchoge chose to use it in his Breaking2 marathon the next spring, but I chose not to write about it until I saw some evidence that it worked as claimed. This would soon be forthcoming, Reuterswärd promised. But years passed without any published data.

“When we did the drinks, we learned a lot from the mistakes we did regarding publications,” Sköld says. “We are very Swedish, and we were kind of naïve.” They figured no one would believe their internal data, he says, so they waited for independent researchers to test their claims. But the world of nutrition is different from the world of pharmaceuticals, where Sköld cut his teeth. No independent research was forthcoming. This time, Maurten has funded Sparks and Gough to carry out independent testing of their baking soda claims. The funding is still a potential source of bias, but it’s better than no research at all, Sköld says.

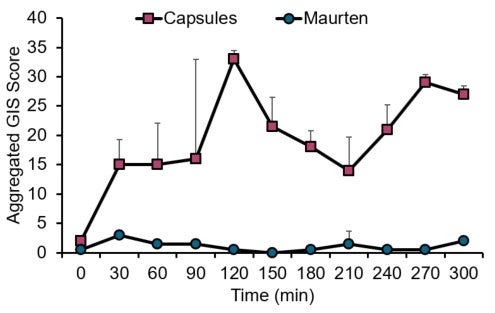

The tests are just getting started, but the initial results are “very promising, especially in terms of reducing GI symptoms,” Gough says. At the recent International Sport and Exercise Nutrition conference in Manchester, Sparks presented pilot data from a grand total of two subjects. It’s not exactly publishable, but the visual he presented is certainly eye-catching. The vertical axis here is a total score summing up negative GI symptoms over time (on the horizontal axis) after taking baking soda either as a capsule or in Maurten’s hydrogel:

When Reuterswärd contacted me this time, he pitched the story as an exploration of fairness in sport. Maurten was worried, he said, that the supplement was just too good. Certainly, after seeing the evidence so far and hearing the list of athletes using it, you can’t help wondering if the playing field has been a bit tilted, if only by about 1 percent. Heijboer, the head of performance at Jumbo-Visma, told his riders they were the only team with access to it: “So not only was it a nutritional gain, but also a psychological one.” Sprouse, from EF Education-EasyPost, confirms this: the peloton started hearing rumors about Jumbo-Visma’s edge more than a year ago, which sparked in some riders a “frantic desire” to get some. But they couldn’t get it.

Even when it’s released, the initial price is 60 euros (about 65 dollars) for four doses. That’s some very pricey baking soda, especially if you believe it could be helpful in training as well as racing. Like carbon-plated running shoes, the combination of price and sponsor conflicts may mean that availability on the free market doesn’t translate into a perfectly even playing field. On the other hand, the frenzy about Roglič’s soup is reminiscent of the ketone mania that gripped the peloton a decade ago. When supply was constrained, cyclists were desperate to get their hands on it and convinced it was skewing race results. Now that anyone can buy it for $85, interest has waned. Some people in the cycling world still believe it can be useful, Sprouse says, but it’s no longer considered a game-changer.

Personally, I find it hard to get worked up about the ethics of baking soda. It’s like caffeine: clearly performance-boosting, but so common and harmless—diarrhea aside—that you can’t construe it as cheating. Still, finding a better way to deliver it could make a big difference, just as it did with carbs. Baking soda, instead of a danger-fraught experiment, could become a standard part of the serious endurance athlete’s arsenal. “It’s unlikely to be revolutionary, but it could be useful” is how Sprouse puts it. Sköld, for his part, is just eager to get it out in the open. “We don’t know how the world will react,” he says. “But I believe we know how the athletes will react. They really like it.”

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.