Measuring Developer Productivity: Real-World Examples

👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a free issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. To get issues like this in your inbox, weekly, subscribe:

Before we start, two notes:

-

I’m speaking at Craft Conference 2024. I’ll be delivering the keynote entitled “What’s Old is New Again” at Craft Conference 2024, on 30-31 May, in Budapest, Hungary. There will also be a book signing for The Software Engineer’s Guidebook. The conference has an impressive lineup of 40+ speakers. Tickets are currently selling at a 15% discount, ending this week. I’ll also be hanging out and meeting people at the event; I hope to see some of you there!

-

I’m hiring: for a Tech Industry Researcher (part-time) for The Pragmatic Engineer. This is not a typical position – then again, this newsletter is also not a typical publication. More details.

Last year, the most popular article in The Pragmatic Engineer was “Measuring developer productivity? A response to McKinsey,” which I wrote in collaboration with

. Clearly, the topic of measuring developer productivity resonated with many readers!

One criticism of the article was that Kent and I offered frameworks for thinking about developer productivity, but we didn’t provide a blueprint to follow when addressing how developers should be measured.

However, this was intentional because – like many complicated questions – the answer starts with “it depends.” But it’s been bugging me that I didn’t have more concrete answers about which metrics to measure, especially because this newsletter covered how LinkedIn and Uber track developer efficiency.

So, I reached out to someone with close to a decade of experience in precisely this field. Abi Noda is coauthor – alongside the creators of DORA and SPACE – of the widely-cited whitepaper, DevEx: a new way to measure developer productivity. He’s also the cofounder and former CEO of developer productivity tool Pull Panda, has worked on software delivery measurements at GitHub, and is CEO and cofounder of developer insights platform, DX. Abi also writes the Engineering Enablement newsletter. For transparency, I’m an investor and advisor to DX.

In his work, Abi has interviewed teams responsible for measuring developer productivity at 17 well-known tech companies. In this article, we focus on a selection of businesses; from the largest, to medium-sized scaleups.

In this issue, we cover:

-

Developer productivity metrics at 17 tech companies

-

Google: a Big Tech

-

LinkedIn: another Big Tech

-

Peloton: a mid-sized tech company

-

Scaleups and smaller companies

-

Interesting findings

-

How to select your own metrics to measure

With that, it’s over to Abi.

1. Developer productivity metrics at 17 tech companies

There’s been a lot of debate recently about how to measure developer productivity. There’s no question it’s a complex problem: software engineering is knowledge-based work, so even the question of what it means to be “productive” is tricky. Then, you start getting into metrics that can be harmful or be gamed, and it’s obvious how conversations can quickly become muddled or pedantic.

But there’s a simpler way. Many companies have dedicated teams focused on making it easier for developers to ship high quality software. You’ve probably heard of them: they’re often called Developer Productivity (DevProd,) or Developer Experience (DevEx) teams. What if, instead of debating how to measure productivity, we looked into what these teams actually measure?

The thing about these teams is they need developer productivity metrics in order to do their jobs. To prioritize the right projects, they need to be able to measure how productive engineering teams are, and what’s hindering them. They also need metrics to track and show that their work actually moves the needle. By studying which metrics these teams use, I think we can learn a lot about which ones are genuinely helpful.

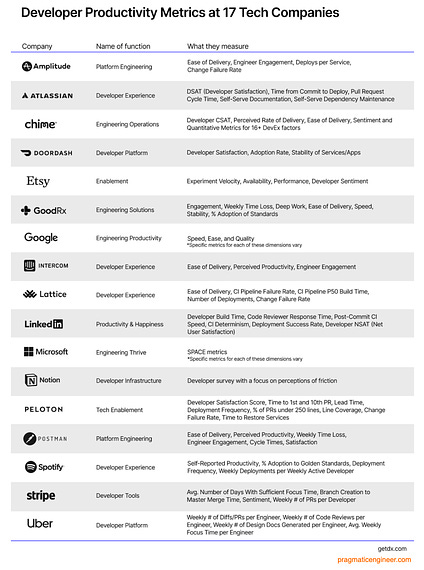

To find this out, I reached out to 17 leading tech companies, asking about the metrics their Developer Productivity functions or teams use. Below is an overview of developer productivity metrics used across different companies, at time of publication. Here’s what they shared:

You can see there’s a wide range of metrics in use, including:

-

Ease of Delivery (Amplitude, GoodRx, Intercom, Postman, Lattice)

-

Experiment Velocity (Etsy)

-

Stability of Services / Apps (DoorDash)

-

SPACE metrics (Microsoft)

-

Weekly focus time per engineer (Uber)

Every company has its own tailored approach to measuring its engineering organization’s efficiency. For this article, I’ve chosen four companies by size, in decreasing order, and do a deepdive on each one:

-

Google (more than 100,000 employees)

-

LinkedIn (more than 10,000)

-

Peloton (more than 1,000 but well below 10,000)

-

Scaleups (between 100 and 1,000 engineers) similar to Notion, Postman, Intercom, Amplitude, GoodRx and Lattice

If you’re interested in learning more about the metrics defined in the table above, get a detailed report emailed to your inbox.

2. Google’s approach

I often point to Google as a model for how to measure developer productivity. Still, plenty argue that replicating Google’s level of investment is unattainable (“we’re not Google.”) While it’s true some of the metrics Google captures are out of reach for most companies, I believe organizations of any size can adopt Google’s overall philosophy and approach.

The Developer Intelligence team is a specialized unit in Google, dedicated to measuring developer productivity and providing insights to leaders. For instance, they help internal tooling teams understand how developers are using their tools, whether they’re satisfied with them, and how fast, reliable, or intuitive the tools are. They also partner with executives to understand the productivity of their organizations.

Whether measuring a tool, process, or team, Google’s Developer Intelligence team subscribes to the belief that no single metric captures productivity. Instead, they look at productivity through the three dimensions of speed, ease, and quality. These exist in tension with one another, helping to surface potential tradeoffs.

To illustrate, consider the example of measuring the code review process. The team captures metrics for each dimension:

-

Speed: How long does it take for code reviews to be completed?

-

Ease: How easy or difficult is it for developers to navigate the code review process?

-

Quality: What is the quality of feedback received from a code review?

Of course, the specific metrics used vary depending on what’s being measured. But the three core dimensions remain constant.

Google uses qualitative and quantitative measurements to calculate metrics. It relies on this mix to provide the fullest picture possible:

“We will measure using logs for speed. We’ll also measure people’s beliefs of how fast they think they’re going. We will also follow this up with diary studies and interviews to make sure that this all lines up and matches up together. We’re talking about mixed methods.”

– Ciera Jaspan, tech lead manager within the Developer Intelligence team

Many metrics that Google uses are captured via behavioral methods:

“Technical debt is a thing that we’ve run into that is just hard to find good objective metrics that tell you how much and where and whether it’s a problem. Surveys can help you measure things that you don’t know how to measure objectively. It can also help you measure things that are in principle not measurable objectively.”

– Collin Green, UX research lead and manager within Developer Intelligence

3. LinkedIn

LinkedIn employs more than 10,000 people and operates independently within Microsoft. Like Google, it has a centralized Developer Insights team responsible for measuring developer productivity and satisfaction, and delivering insights to the rest of the organization. This team sits within the broader Developer Productivity and Happiness organization, which focuses on reducing friction from key developer activities and improving the internal tools they use.

The Pragmatic Engineer previously covered LinkedIn’s approach to measuring developer productivity. I’ll recap the three channels LinkedIn uses to capture metrics:

-

Quarterly survey: The Developer Insights team uses a quarterly survey to assess the developer experience across a range of tools, processes, and activities. It includes approximately 30 questions, which developers answer in around 10 minutes. The survey is delivered through a proprietary platform developed and maintained by the Developer Insights team, allowing for advanced customization and personalization of survey questions based on data collected from real-time feedback and metrics systems.

-

Real-time feedback system: To capture feedback between quarterly surveys, LinkedIn has developed a real-time feedback system, which tracks events and actions that developers perform within development tools, and sends targeted surveys based on specific triggers. The system uses smart throttling mechanisms to avoid overwhelming developers with feedback requests.

-

System-based metrics: LinkedIn also calculates metrics using data from their systems, providing high precision measurements for things such as build times and deployment frequency. The Developer Insights team maintains a global system for ingesting and analyzing this data, which they call the Developer Insights Hub (or iHub). This system allows teams across LinkedIn to create custom dashboards and metrics tailored to their needs.

What the previous The Pragmatic Engineer article on LinkedIn didn’t cover, was the specific metrics LinkedIn uses. Here are examples of those which the company focuses on:

-

Developer Net User Satisfaction (NSAT) measures how happy developers are overall with LinkedIn’s development systems. It’s measured on a quarterly basis.

-

Developer Build Time (P50 and P90) measures in seconds how long developers spend waiting for their builds to finish locally during development.

-

Code Reviewer Response Time (P50 and P90) measures how long it takes, in business hours, for code reviewers to respond to each code review update from the author.

-

Post-Commit CI Speed (P50 and P90) measures how long it takes, in minutes, for each commit to get through the continuous integration (CI) pipeline.

-

CI Determinism is the opposite of test flakiness. It’s the likelihood a test suite’s result will be valid and not a flake.

-

Deployment Success Rate measures how often deployments to production succeed.

Like Google, LinkedIn’s Developer Insights team looks at both qualitative and quantitative metrics in each area. For example, for build times, they compare the objective measure of how long builds take, with how satisfied developers are with their builds:

“Even if the quantitative metrics say that everyone’s builds are fantastic, if developers are saying ‘I hate my builds,’ you should probably listen to that.“

– Grant Jenks, Senior Tech Lead for the developer insights platform

The quantitative metrics above are typically calculated using medians. However, one challenge when using median values is that the metric doesn’t move, even if the outlier metrics improve. In one instance, the LinkedIn team reduced excessively long front-end build times from 25 seconds to 3 seconds. This was a big win! However, because of the distribution curve of the data, the improvements weren’t moving the median materially.

Winsorized means are a way to recognize improvements made within the outlier metrics. Winsorized means are calculated by replacing high and low end values with numbers closer to the middle. Here is how Grant Jenks explains this approach:

“What a winsorized mean does is it says: figure out your 99th percentile and instead of throwing away all the data points that are above the 99th percentile, clip them. So if your 99th percentile is a hundred seconds and you have a data point that’s 110 seconds, you cross out 110 and you write a hundred, and now you calculate your (winsorized) mean that results in a more useful number.”

The Developer Experience Index is a special metric LinkedIn provides to teams. This is an aggregate score based on a number of different metrics, such as those listed earlier.

Grant generally cautions against using such composite scores, due to the complexity of developing and calibrating them. As he shared:

“We don’t track the Developer Experience Index over time. We reserve the right to change the aggregation and the weightings behind it at any time. We tell people not to ever put this metric into an OKR, either.”

For more details, see Abi’s podcast interview with LinkedIn.

4. Peloton

Peloton employs around 3,000-4,000 employees, so while being a large company, it’s considerably smaller than LinkedIn. Peloton’s measurement approach began with capturing qualitative insights through developer experience surveys. Later, they started pairing this data with quantitative metrics for a fuller picture.

Peloton measures productivity by focusing on four key areas: engagement, velocity, quality, and stability. Here are some of the metrics used:

-

Engagement: Developer Satisfaction Score

-

Velocity: Time to 1st and 10th PR for all new hires, Lead Time, Deployment Frequency

-

Quality: % of PRs under 250 lines, Line Coverage, Change Failure Rate

-

Stability: Time to Restore Services

The developer experience survey – by which many of these metrics are measured – is led by Peloton’s Tech Enablement & Developer Experience team, which is part of their Product Operations organization. The Tech Enablement & Developer Experience team is also responsible for analyzing and sharing the findings from their surveys with leaders across the organization.

Here’s how Thansha Sadacharam, head of tech learning and insights, explains the root of their survey program:

“I very strongly believe, and I think a lot of our engineers also really appreciate this, that engineers aren’t robots, they’re humans. And just looking at numbers or looking at certain key metrics don’t drive the whole story. So for us, having a really comprehensive survey that helped us understand that entire developer experience was really important.”

The survey happens twice a year. It’s sent to a random sample of roughly half of developers. With this approach, individual developers only need to participate in one survey per year, minimizing the overall time spent on filling out surveys, while still providing a statistically significant representative set of data results.

For more, check out Abi’s interview with Thansha Sadacharam.

5. Scaleups and smaller companies

There are several scaleups on the developer productivity list: Notion, Postman, Amplitude, GoodRx, Intercom, and Lattice. These companies range from employing around 100 to 1,000 engineers. One thing many of these scaleups focus on is measuring “moveable metrics.” A moveable metric is one that developer productivity teams can “move” by impacting it positively or negatively with their work. Moveable metrics are helpful for developer productivity teams to showcase their own impact.

Here are some commonalities in what these companies measure:

1. Ease of Delivery (moveable). Most of these companies measure ease of delivery; a qualitative measure of how easy or difficult developers feel it is to do their job.

Several DevProd leaders shared that they use this metric as a “north star” for their work, since their teams’ goal is to make developers’ lives easier. This metric is also useful for showing impact thanks to it being fairly moveable. From a theory standpoint, this metric also captures key aspects of the developer experience, such as cognitive load and feedback loops.

2. Engagement. Most of these companies also track engagement, a measure of how excited and stimulated developers feel about their work. While engagement is commonly measured in HR engagement surveys, DevProd teams also cited focusing on Engagement for these reasons:

-

Developer engagement and productivity are closely linked. In other words, “happy developers are productive developers,” and so developer engagement can be viewed as an indicator of productivity.

-

A real benefit of measuring engagement is to counterbalance other metrics which emphasize speed. Delivering software faster is good, but not at the expense of developer happiness decreasing.

3. Time Loss (moveable). GoodRx and Postman pay attention to the average amount of lost time. This is measured by the percentage of developers’ time lost to obstacles in the work environment. This metric is similar to ease of delivery, in that it provides DevProd teams a moveable metric which their work can directly impact.

This metric can be translated into dollars: a major benefit! This makes Time Loss easy for business leaders to understand. For example, if an organization with $10M in engineering payroll costs reduces time loss from 20% to 10% through an initiative, that translates into $1M of savings.

4. Change Failure Rate. This is one of the four key metrics from the DORA research program. It’s a top-level metric tracked by several companies, including Amplitude and Lattice. The DORA team defines the change failure rate like this:

“The percentage of changes to production or releases to users result in degraded service (for example, lead to service impairment or service outage) and subsequently require remediation (for example, require a hotfix, rollback, fix forward, patch).”

Lattice measures change failure rate as the number of PagerDuty incidents divided by the number of deployments. Amplitude measures it as the P0s (priority zeros) – the most important priorities – over production deploys. The P0 count goes through PagerDuty, and the deploy count is from their continuous delivery service, Spinnaker.

6. Interesting findings

Several interesting findings stand out to me after reviewing how 17 tech companies benchmark engineering productivity:

DORA and SPACE metrics are used selectively

I expected the metrics from DORA and SPACE to appear more frequently, since they’re often thought of as “industry standard.” But only one company, Microsoft, mentioned embracing one of these frameworks wholesale, which makes sense since they authored the SPACE framework.

For other companies, some individual metrics from these frameworks were mentioned only as components in a broader, more holistic measurement strategy.

Broad adoption of qualitative metrics

Across the board, all companies shared that they use both qualitative and quantitative measures. For example, Developer Engagement was shared as a metric by Intercom, Postman, and Peloton. Companies including Atlassian, Lattice, and Spotify similarly rely on self-reported measures.

This highlights a marked shift in how top companies are approaching developer productivity measurement. Five years ago, most of these companies were likely focused exclusively on quantitative metrics. Our recent ACM paper provides a framework for leveraging qualitative metrics to measure developer experience. For more, check out the article, A new way to measure developer productivity – from the creators of DORA and SPACE.

A big emphasis on “focus time”

I was surprised by how many companies track “focus time” as a top-level metric. Although research has shown “deep work” to be an important factor in developer productivity, I didn’t expect as much attention on it as I found. Stripe and Uber shared specific metrics, such as “Number of Days with Sufficient Focus Time,” and “Weekly Focus Time Per Engineer, while other companies mentioned deep work as a topic they measure in their developer survey programs. The Pragmatic Engineer previously covered how Uber measures engineering productivity.

Unique metrics

There’s quite a bit of overlap in what different developer productivity teams are measuring. But there are also a few unique metrics worth highlighting:

-

Adoption Rate (DoorDash, GoodRx, and Spotify.) How many developers actively use a product or service. Spotify’s version is a measure of how many developers have adopted its Golden Standards.

-

Design Docs Generated per Engineer (Uber.) Design docs are written by engineers for non-trivial projects before they start meaningful work—the idea is to get feedback early and ultimately decrease the time taken to complete a project. Their metric tracks how frequently developers are following this practice.

-

Experiment Velocity (Etsy.) Former CTO, Mike Fisher (who writes the tech newsletter

) says that at Etsy, each team designs and runs its own experiments to assess how users will respond to new features. This practice is a core aspect of their engineering culture, facilitating a culture of learning and helping teams stay focused on the customer. Etsy has developed an in-house experimentation platform to track the progress of these experiments. Metrics include how many experiments start each week, how many have been stopped, and how many have a positive hit rate. For context, the ultimate goal is to measure learning velocity.

-

Developer CSAT/NSAT (Chime and LinkedIn.) LinkedIn measures Developer NSAT (Net User Satisfaction,) which tracks how satisfied developers are overall with their development systems. Another metric listed on the report is a Developer Customer Satisfaction (CSAT) score for the tools and services that developers use. CSAT is captured via quarterly developer surveys. These metrics are different: the CSAT metric focuses on specific tools, whereas LinkedIn’s NSAT measures developers’ satisfaction with all tools, overall. Also, the CSAT metric is calculated as a percentage of positive responses, whereas LinkedIn’s is the percentage of satisfied responses subtracted by the percentage of dissatisfied responses.

7. How to select your own metrics to measure

I always recommend borrowing Google’s Goals, Signals, Metrics (GSM) framework to help guide metric selection. Too often, teams jump to metrics before thinking through what they actually want to understand or track. The GSM framework can help teams identify what their goal is, and then work backwards to pick metrics that serve this.

Ciera Jaspan, from Google’s Developer Intelligence team, explains how the GSM process is used at Google:

“We always encourage people to follow the goal, signals, metrics approach. We ask them to first write down your goals. What is your goal for speed? What is your goal for ease? What’s your goal for quality? Write those down first and then ask your question of: ‘what are the signals that would let you know that you’ve achieved your goal?’ Regardless of whether they’re measurable.

Signals are not metrics. What would be true of the world if you’ve achieved your goal? At that point, try to figure out what are the right metrics.”

Choosing metrics as a Developer Productivity team

Start by defining your charter. Why does your DevProd team exist? Here are three examples of DevProd team charters:

-

Google: “Make it fast and easy for developers to deliver great products.”

-

Slack: “Make the development experience seamless for all engineers”

-

Stripe: “Make software engineering easier.”

Work backwards from your goals to define the top-level metrics. If you want to make it easier for developers to deliver high quality software, how will your team know whether you do that? You might want to look for signals such as:

-

How easy it is for developers to deliver software

-

How quickly developers deliver software

-

The quality of software delivered

For each category, define metrics to help track how it’s going. For example:

-

Speed = Perceived Delivery Speed, Perceived Productivity

-

Ease = Ease of Delivery, Deployment Lead Time, Build Failure Rate

-

Quality = Incident frequency, Perceived Software Quality

These metrics should sound similar to many of those discussed in this article.

Use similar top-level metrics for your DevProd team to convey the value and impact of your efforts. With the right metrics, you can keep everyone aligned within and outside of your team.

Operational metrics are ones you’ll want to tie to specific projects or objective key results (OKRs.) Operational metrics are used by many DevProd teams on top of the top-level metrics.

Operational metrics include:

-

Developer satisfaction with specific tools

-

Adoption rate of a particular service

-

Granular measurements of developers’ workflows.

-

… and many others!

I wish there was a good, one-size-fits-all solution, but the reality is that there is not. What is important: choose metrics your team can – and does! – control. Avoid targeting high-level key metrics that can be affected by factors beyond your control.

If you’re an engineering leader

If you’re a CTO, VPE, or Director of Engineering, then it’s almost certain your scope is broader than the definition of developer productivity discussed in this article. When I speak with engineering leaders who are figuring out metrics, they’ve often been asked for metrics by their CEO, or the leadership team.

In this case, my best advice is to reframe the problem. What your leadership team wants is less about figuring out the perfect productivity metrics, and much more about feeling confident that you’re being a good steward of their investment in engineering.

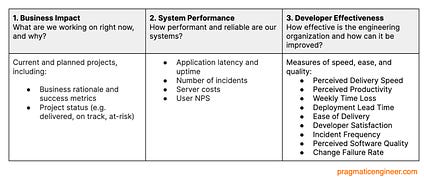

To demonstrate good stewardship, consider selecting metrics that fall within three buckets:

1. Business impact. You should report on current or planned projects, alongside data that addresses questions like:

-

Why are these the right things to build now?

-

How does this project make the business money, or otherwise support its goals?

-

Is this project on track or delayed?

This type of reporting is often seen as the product team’s responsibility. Still, only engineering can represent the full set of projects being worked on. A good example is a database migration project, which is unlikely to be on the Product team’s roadmap.

2. System performance. Engineering organizations produce software, so stakeholders will want to know about the health and performance of these systems. You’ll need to answer question like:

-

Are engineering systems fast and reliable?

-

Is our infrastructure secure and well-maintained?

-

Are users satisfied with the services they use?

Useful metrics to report here include uptime, number of incidents, and product NPS scores. If you have a dedicated Infra or UXR team, they’re likely capturing metrics that fall in this bucket.

3. Engineering effectiveness. Stakeholders want to know how effective the engineering organization is, and how it can be improved. This article has been primarily focused on this, so you can apply what we’ve learned from how DevProd functions measure things.

Takeaways

Gergely here. Thanks, Abi, for this deep dive into dev productivity metrics.

It’s little surprise that the largest tech companies already measure developer productivity. I found it a bit more surprising that businesses with engineering teams in the low hundreds – such as Lattice and GoodRx – also do this.

Measuring a mix of qualitative and quantitative metrics is common across all these companies. They all measure several things, and the metrics often capture different areas. For example, Stripe measures both:

-

Average number of days with sufficient focus time (qualitative and quantitative)

-

Weekly PRs per developer (quantitative)

Both these measurements give a different view of productivity, and help to forecast problems. If Stripe only measured weekly PRs, they might see a team that’s smashing it by shipping 10 PRs per developer, per week. But what if they see that team has zero days of sufficient focus time? That team is likely to be close to burnout, at which point their number of PRs might drop.

Take inspiration from the wide range of measurements each company uses. Most businesses in the survey measure at least 5-6 different metrics. There is a big variance in what they focus on, much of it based on their own priorities and engineering cultures.

And I cannot nod enough to Abi’s advice on how to choose your own metrics: start with the problem you want to solve. Is it shipping frictionless, retaining developers by keeping them happy and satisfied, raising the quality of software shipped, or something else? Then work backwards from there!