Understanding the Circles of Influence, Concern, and Control

17 Nov 2023

1 Jun 2023 by

In our increasingly complex world, we often encounter a multitude of challenges that can leave us feeling overwhelmed and disempowered.

Many of the things that concern us today are clearly beyond our control, yet we cannot seem to stop worrying about them. However, worrying about what we cannot control is not a wise use of our limited energy.

The ancient Stoic philosophers held that we can live more peaceful and fulfilling lives if we focus our attention and energy on what we can control.

Psychologists have expanded on the Stoic idea of the two spheres of control and added a “sphere of influence” into the mix: a gray zone between what we can and cannot control.

Spending our mental energy wisely is of great importance, especially for those of us who are prone to anxiety, worrying, and ruminating and those who are exhausted. Let’s explore these circles of influence and how they can aid your clients.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Resilience Exercises for free. These engaging, science-based exercises will help you effectively deal with difficult circumstances and give you the tools to improve the resilience of your clients, students, or employees.

-

5 Huge Mistakes People Make In Fort…

This Article Contains

Understanding the Theory: A Model and Diagram

The Stoic philosophers Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius all reflected extensively on the circle of control.

Epictetus (2009, p. 135) wrote, “Some things are within our power, while others are not. Within our power are opinion, motivation, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever is of our own doing; not within our power are our body, our property, reputation, status, and, in a word, whatever is not of our own doing.”

The Stoics agreed that within our control are our thoughts, emotions, and interpretations, as well as our reactions and actions. These are the things that we should focus on and work to improve.

By contrast, they held that there are things that are clearly outside of our control. These include other people’s actions, feelings, and opinions of us, the weather, the economy, and random events in life. These are the things that we should not waste our energy worrying about.

The circle of control can be a difficult concept to grasp, especially in a world where we often feel like we need to be in control of everything. Westerners also have a tendency to overestimate their agency and the things they can actually influence (Nisbett, 2003).

However, accepting the idea that there are some things that we simply cannot control can be profoundly liberating. It can help us let go of anxiety and stress and focus on the things that we can actually change.

Again, Epictetus (2007, p. 3) put it most memorably: “Happiness and freedom begin with a clear understanding of one principle: Some things are within our control, and some things are not.”

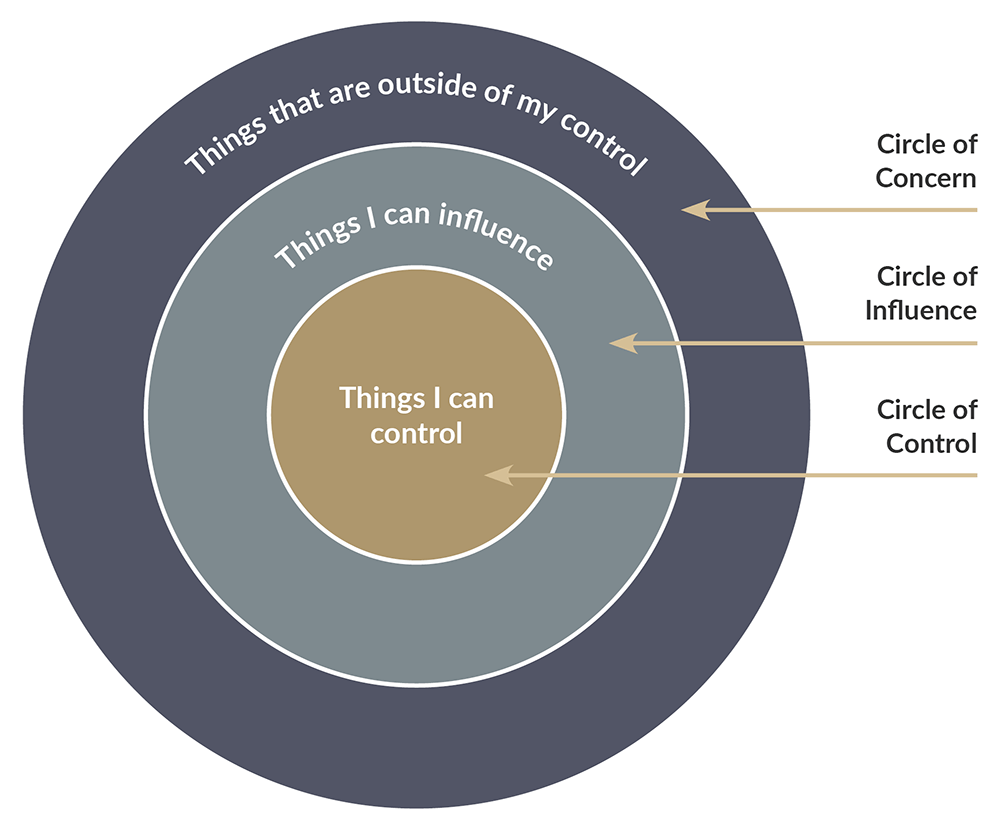

In the diagram above, you will see three concentric circles of different sizes embedded within each other.

The first and smallest circle at the center is the circle of control, representing aspects of our life over which we have direct control. It is the sphere in which we can effect change. The circle of control symbolizes the areas where we can take meaningful action and make a positive difference.

Most philosophers and psychologists agree that this area encompasses our inner lives: our thoughts, beliefs, emotions, interpretations, and judgments of external events. We should try to focus most of our attention, energy, and resources on this region.

The second, slightly larger circle is the circle of influence, representing the intersection of factors within our immediate control and those that fall outside of our area of control.

This is, quite literally, a gray zone. We may or may not have the power to expand our influence into this region to create change. We can certainly try. It is wise to spend some of our energy in that sphere, bearing in mind that we can control our efforts in this sphere, but not necessarily outcomes.

The third and largest, outermost circle in the diagram represents the circle of concern. This circle encompasses a broader range of external factors, challenges, and circumstances that we may care about but which are clearly beyond our control.

This circle includes the economy, climate, and weather, but also most of the actions, reactions, behaviors, and feelings of other people. Ryan Holiday (2016, p. xi) puts it succinctly: “We cannot control the world around us, but we can control our reactions to it.”

There are excellent reasons for applying this model in our own life. For example, Luthans et al. (2008, p. 132) established that “individuals who focus on the circle of control are more likely to be resilient in the face of stress and adversity.”

Rohleder and Chen (2013, p. 248) found that “the circle of control is a useful cognitive tool for individuals to manage their emotional reactions to stressful situations.” Van den Berg et al. (2017) arrived at a similar conclusion in their three-wave longitudinal study on the role of perceived control in the link between perceived economic hardship and subjective wellbeing.

Karademas (2006, p. 1281) found evidence that “individuals who have a strong sense of control over their lives, as indicated by a larger circle of control, are more likely to experience positive emotions and subjective wellbeing.”

Leary et al. (2016) showed that the circle of control is a useful tool for people to identify their strengths and weaknesses and develop a better sense of self-efficacy.

Finally, Donald Robertson (2013, p. 59) writes, “By focusing on what we can control, we can develop a sense of inner calm and resilience that helps us to cope with the challenges of life.”

The Circle of Concern

The circle of concern includes the events, situations, reactions, and phenomena that are clearly outside of our spheres of control and influence.

They include, for example, our pasts, where we were born, who our parents are and how they treated us, government policy, economic developments, war, illnesses that may befall us, accidents, traffic, people’s behavior, the media, redundancies, and deaths of loved ones.

In order to live full and rewarding lives, we need to learn to let go of trying to control anything that lives in this circle. This is of course much easier said than done. It involves the capacity to let go of our desire for control and, at the same time, to seek to control unhelpful ruminating.

As William B. Irvine clarifies, this does not mean that we stop caring about the things that are in the circle of concern. Rather, it means that we stop kidding ourselves about our ability to change them. He writes, “The circle of control is not a prescription for detachment or indifference. It is a way of focusing our attention and energy on what really matters, so that we can live more fully and authentically” (Irvine, 2009, p. 69).

Download 3 Free Resilience Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients to recover from personal challenges and turn setbacks into opportunities for growth.

Download PDF

The Circle of Influence

The circle of influence is perhaps the most controversial part of the model. The Stoics, who were, it has to be said, quite pessimistic about individual agency in the public sphere, didn’t believe in it at all. Many modern-day psychologists, by contrast, do.

Today, we live in societies that differ quite dramatically from the civilizations of Ancient Greece and Rome. Many are democracies that subscribe to the charter of human rights. The Stoics were perhaps overly pessimistic about our influence and efficacy partly because they lived in the age of tyrannical emperors, who could destroy fortunes and take lives on a whim. They couldn’t trust in fair process, stable laws, and clear balances of power.

We can see the circle of influence as the point where inner meets outer. What we place in our circle of influence also depends on how optimistic or pessimistic we are and how we think about our agency and self-efficacy. We may overestimate our agency and influence, or else we may underestimate it, especially when we feel depressed and helpless (Seligman, 2011; DeAngelis, 2015).

Some things we do in the circle of control radiate outward. They have consequences for ourselves and those around us. The way we behave and show up impacts others and our projects. It can positively influence certain situations and outcomes and thereby expand our circle of control.

For example, how well we prepare and show up for a job interview will increase our chances of getting the job. How hard we work and how strategic we are about our decision-making may determine the success of our business. But not always — and that is precisely the point.

Sometimes, external circumstances will trump all our efforts in the circle of control. A global pandemic, for example, led to the collapse of many businesses, regardless of how hard their owners worked or how strategic they were.

The Circle of Control

As mentioned before, what we can control includes our responses to external events that are outside of our control.

We can, to a certain extent at least, try to control our thoughts, judgments, interpretations, and emotions.

We may use meta-cognitive Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy techniques, or journal and practice mindfulness and radical acceptance. We can work on our mindsets and seek the help of therapists and coaches to develop our resilience and inner resources.

Besides our inner lives, we can also control most of our behaviors. As an example: While we cannot control getting an illness, we can improve our general health and wellbeing hoping to prevent illness. We can choose to eat well, get enough sleep, drink enough water, exercise, and not indulge in toxic substances.

We can also control some of our reactions and choose not to respond in anger or fear to certain stimuli or jump straight into impulsive action without due reflection. We can aim to make conscious, deliberate choices in life that are aligned with our core values.

Applying the Theory: 3 Real-Life Examples

Joe has been seeing a career counselor and has an upcoming job interview. To prepare for the interview, Joe is advised to accept what he can control. He can control how well he rests beforehand and how well he prepares for the interview. He can control what he wears, how to present himself, and how to answer the interviewer’s questions.

But Joe cannot control how good the other candidates are, how apt a fit for the position he is considered, or ultimately, whether or not he gets the job. Worrying about that outcome will make anyone anxious. By accepting that the outcome is outside of his control, by contrast, he can let go of that worry and simply focus on doing his very best in preparing for and performing at the interview.

Sue is struggling against teacher burnout. Her environment is very stressful, and she is constantly worrying about the behaviors and attitudes of her students, even though she knows she can’t really control them.

During therapy, Sue is introduced to the concept of the circle of control and encouraged to focus on the things she can control: her own attitude and reflections, her teaching style, how she responds to bad behavior, and the way she shows up in her interactions with students. This shift in perspective allows Sue to let go of her worries and approach her job with a greater sense of calm and equanimity.

Rick is dealing with a chronic health condition that makes him feel helpless and out of control. He constantly worries about his symptoms and tries to control his body’s reactions.

But after reading about the circle of control, he realizes he needs to focus on the things he can control: his relationships, diet, exercise routine, self-care practices, and stress management techniques. By making positive changes in these areas, Rick could improve his health and feel more empowered in his daily life.

3 Activities and Exercises for Adults

As described with the real-life examples above, aiding your clients in accepting what they can and cannot control can help them face many of life’s challenges.

Below are a few simple exercises your clients can use during therapy or counseling.

Define and assess your stressors

List your core stressors on a sheet of paper. Next, draw concentric circles on another paper, representing circles of concern, influence, and control. Place each stressor in the appropriate circle.

Finally, look at the stressors that are within your control. Compile a list with a few action points: How are you going to focus more closely on what is in your control?

Cultivate a growth mindset

Embrace a growth mindset, recognizing that challenges and setbacks are opportunities for learning and personal development. Cultivate self-compassion and optimism, reframing obstacles as stepping stones toward growth and resilience. The title of Ryan Holiday’s book on Stoicism beautifully encapsulates this idea: The Obstacle Is the Way.

Practice gratitude and appreciation

Engage in gratitude practices to shift your focus toward the positive aspects of your life and work. Express appreciation for the support and contributions of others, nurturing a culture of empowerment and collaboration within your circles.

2 Worksheets and Templates for Therapists

Worksheets are helpful tools to use when assisting your clients with a mind shift.

This worksheet and template by the University of Victoria is an excellent starting point. It gives clients a nice indication of what might be placed in the different circles. But remember, the circle of influence is most definitely a gray zone. What we wish to put in here might vary significantly from person to person.

If you want to avoid the circle of influence, you can opt for the more straightforward Stoic version, which only features a circle of control and a circle of concern. An example can be found here:

Fascinating Books on the Topic

A great starting point for understanding the principles behind the circle of control idea is Epictetus’s Discourses. In fact, any of the classic Stoic texts will give you wonderful insights into what is and what is not beyond our control, including Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic, Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, and Epictetus’s Of Human Freedom.

Alternatively, you can also read Stoic-inspired self-help. There are some excellent books out there. I particularly like Massimo Pigliucci’s How to be a Stoic and Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is the Way. Both do a great job at explaining Stoic doctrine, why it matters, and how we may apply Stoic principles in our own daily lives. The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman includes 365 short daily Stoic meditations.

You may also enjoy Donald Robertson’s Stoicism and the Art of Happiness: Practical Wisdom for Everyday Life, Donald Robertson’s How to Think Like a Roman Emperor: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, and William B. Irvine’s A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy.

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

Since Stoicism is such a central component of our article today, you might want to read more about it in our article exploring powerful Stoic Mindfulness Meditations.

For a more practical approach to resilience, I’d recommend this article sharing resilience exercises.

Lastly, a truly excellent article on gratitude and how we can hone a grateful mindset is Why We Want More and More (and More).

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others overcome adversity, check out this collection of 17 validated resilience and coping exercises. Use them to help others recover from personal challenges and turn setbacks into opportunities for growth.

A Take-Home Message

The question of what we can and cannot control is far from trivial.

With honesty comes the realization that we probably spend a lot of our mental resources on worrying about what is clearly out of our sphere of control. Letting go of what we cannot control, however, is by no means easy.

The ancient Stoics knew that well. For them, cultivating a Stoic mindset was a lifetime pursuit. And yet, practicing the Stoic art of acceptance and letting go is most definitely worth our effort.

Think of it as freeing up large sources of attentional energy that you are currently squandering and putting this energy to work where it can have a positive impact instead. What would become possible? Picture also the sense of inner peace and equanimity you would experience if you fretted less about external circumstances, knowing that what really matters is inside you.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Resilience Exercises for free.

References

- DeAngelis, T. (2015). The circle of influence. Monitor on Psychology, 46(5), 50–56.

- Epictetus. (2007). The art of living: The classical manual on virtue, happiness, and effectiveness (S. Lebell, Trans.). HarperOne.

- Epictetus. (2009). Enchiridion. In G. Long (Ed.), The discourses of Epictetus: With the Enchiridion and fragments (E. Carter, Trans., pp. 135–147). Oxford University Press.

- Holiday, R. (2016). The daily stoic: 366 meditations on wisdom, perseverance, and the art of living. Portfolio.

- Irvine, W. B. (2009). A guide to the good life: The ancient art of stoic joy. Oxford University Press.

- Karademas, E. C. (2006). Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: The mediating role of optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1281–1290.

- Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2016). The benefits of self-compassion and best-self activation for stress management: A pilot study. Psychology and Health, 31(5), 602–619.

- Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., & Patera, J. L. (2008). Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(2), 132–141.

- Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently… and why. Free Press.

- Robertson, D. (2013). Stoicism and the art of happiness: Practical wisdom for everyday life. Teach Yourself.

- Rohleder, N., & Chen, E. (2013). Stress and inflammation in experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage. Biological Psychology, 93(2), 248–256.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Van den Berg, P., Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). The role of perceived control in the link between perceived economic hardship and subjective well-being: A three-wave longitudinal study. Social Indicators Research, 130(3), 1263–1277.

About the author

How useful was this article to you?

Not useful at all

Very useful

Share this article:

Article feedback