In his bestselling book Sapiens, Yuval Harari argues that humans became the dominating species of planet earth because we are the only animal that can cooperate in large numbers. This, he claims, is due to humans’ ability to believe in purely imaginative things and concepts. A company like Google, for example, doesn’t really exist. Sure, there’s the Google.com website and physical Google offices with real Google employees – but the idea of Google as a company is just a fictional concept. It only exists because multiple people believe in it. The same is true for legal systems, nations, religion or money. Every large human cooperation system is based on a fictional idea that only lives in our collective minds.

What Harari doesn’t discuss in his book is the extreme other end of this cognitive ability: Conspiracy theories. I’ve been fascinated by Jon Glover’s recent essay on QAnon, in which he compares conspiracy theorizing to alternate-reality games. Participating in QAnon conspiracies, he says, feels like playing a real-life multiplayer game based on secret insider knowledge.

What Harari doesn’t discuss in his book is the extreme other end of this cognitive ability: Conspiracy theories. I’ve been fascinated by Jon Glover’s recent essay on QAnon, in which he compares conspiracy theorizing to alternate-reality games. Participating in QAnon conspiracies, he says, feels like playing a real-life multiplayer game based on secret insider knowledge.

Social media has made conspiracy theorizing so addictive and immersive that the line between story and reality can become incredibly blurry.

The religion analogy is interesting because it’s a perfect example of why fact checking as a countermeasure is useless. Google, Facebook & co have all introduced fact checks and fake news labels to combat conspiracy theories. It’s naive to think that they will work.

Think about it: Science (which, you could argue, is also a form of fact checking) has been around for centuries trying to debunk most religious beliefs – and yet religion still plays a major role in Western society. If entire education systems teaching millions of people about science haven’t worked, why do you think adding a small fact check disclaimer below a YouTube video would?

In fact – as you would expect from a perfect alternate-reality game – fact checks (and how to circumvent them) have actually long been part of the game.

It’s worth pointing out that science is also just another belief system. We laugh about flat earthers, but how many people can actually explain why the world is round in a scientifically correct way? Most of us don’t know science, we believe in science.

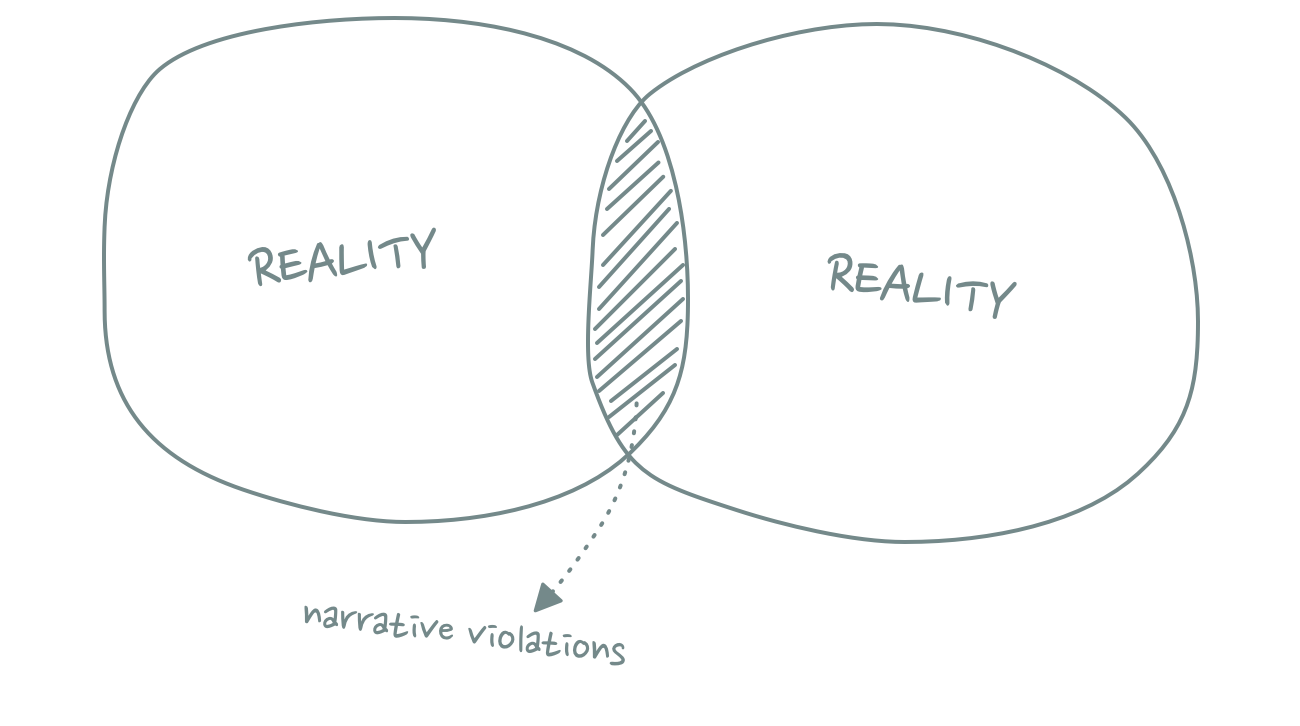

What should give us hope though is the fact that many people believe in *both* science and religion despite their contradictions. This means that multiple realities can co-exist even when they are at odds with each other.

We don’t live in just one reality – we switch between different realities (and play different characters within them). It’s a bit like Westworld, where guests can explore different theme parks: Westworld, Shogunworld, Warworld, etc.

Similar to Westworld, it’s increasingly becoming more difficult to distinguish between what’s real and what isn’t. As Aaron Z. Lewis points out in his brilliant essay You Can Handle the Post-Truth, we have created a fragmented reality with hyper-realistic CGI influencers, bots, deepfakes, AI pretending to be humans and humans pretending to be AI. We don’t live in a single timeline with a single history, but in a variety of “contradictory reality bubbles“.

Bruno Maçães paints a similar picture in his excellent book History Has Begun. America, he believes, is in the process of transforming into a new, post-liberal society, distinct from current Western civilization. It’s a society that has not only been heavily shaped by television but one where reality and fantasy overlap.

This transformation has been in the making for a while: Kennedy had the aura of a movie star and leveraged his image through the medium of television. Nixon created the first political soap opera with the Watergate scandal. And with Reagan an actual movie star moved into the White House.

Trump is the ultimate culmination of this trend. His entire presidency feels scripted. His tweets end with cliffhangers. A House of Cards screenwriter would not have been able to come up with a better story.

Reagan and Arnold Schwarzenegger used the social capital and entertainment skills they acquired as actors to appear more likable and competent as politicians, but at least they tried to be politicians. Trump, on the other hand, uses politics as another stage for his acting performance.

“Americans see the world as an action movie” Maçães writes. I think this became especially apparent during the current covid-19 crisis and the most recent wildfires in California. People in my social media timelines seemed only superficially worried. Instead, their posts contained an underlying sense of excitement about real life finally catching up with the science fiction aesthetics of Blade Runner and Akira.

Perhaps this is Hollywood’s greatest achievement: It gets us excited about our dystopian future. The world might be ending, but at least it’s an ending that’s entertaining to watch.

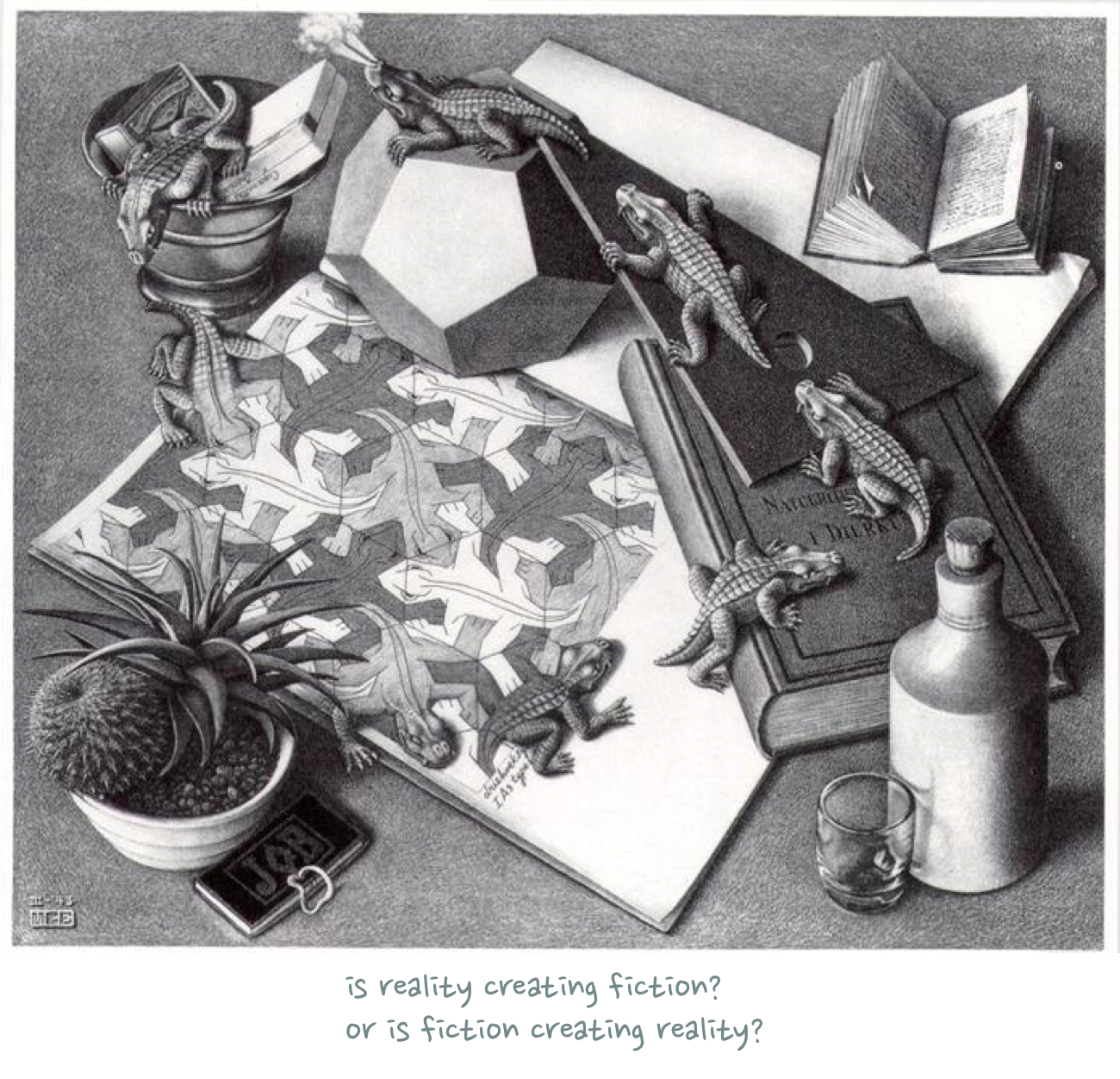

If Hollywood created the fantasy worlds that reality is catching up with today, who is creating the fantasy worlds of tomorrow?

Maçães thinks the answer is Silicon Valley, which he describes as “a fantasy land where engineering talent and capital come together to power the serious project of creating new worlds out of nothing”. It’s one of the most idiosyncratic descriptions of how startups work that I have read. VCs are the new Hollywood studios; founders are the directors and actors.

A founder’s job is essentially to create the most compelling narrative of what their company will look like in 10 to 20 years time. It’s not lying, it’s telling pre-truths. Being contrarian just means that you came up with a novel fantasy plot no one else had thought of yet.

Sometimes founders are able to re-create the fantasy narratives of their pitch decks. Sometimes you end up with Theranos.

And even when you do end up with Theranos, at least you get material for an exciting new Netflix series. Perhaps VCs should buy the movie rights to the startups they invest in as a hedge against their biggest portfolio failures?

The concept of the tech industry as a creator of fantasy worlds immediately reminded me of a conversation I had with my friend Max recently. His theory is that it’s not the lack of tech talent or venture capital that explains why Europe hasn’t been able to create a tech ecosystem on par with the US. It’s the absence of religiosity that has kept Europe from creating its own Google or Facebook. The US is able to create larger companies because it’s able to believe in larger and more ambitious narratives.

Silicon Valley is not just creating new fantasy worlds, it is building tools that allow others to create their own fantasy worlds. Enter social media.

If TV has taught us to think of ourselves as characters in the story of our lives, then social media has allowed us to actually write and edit the script and build fictional characters. Social media is essentially the democratization of virtual world building.

As I wrote in Signaling-as-a-Service, Twitter, Snapchat and Facebook are just massive virtual status arenas that allow us to build social capital through signaling. Some of that social capital might be built on top of real stories and actual achievements, but most of it is not based on reality. Every time you are applying an Instagram filter, you are already changing reality.

It’s not just that we bend reality in our social media narratives, we also play different characters. As Chris Poole already pointed out years ago, we all have multiple (online) identities. There is not just one reflection of yourself – identity is prismatic. Twitter-Julian (armchair intellectual) is not the same as Instagram-Julian (hobby photographer) or Facebook-Julian (high-school drinking buddy). Google Circles and Facebook Lists always got this wrong: They let us change who we shared with, but not who we shared as.

This is why social networking is not a winner-take-all market. We need different channels for our different, contradicting online personas.

The problem is not that we live in multiple realities or that these realities are sometimes at odds with each other. What’s problematic is that we sometimes get so immersed in one virtual world, that we forget about all the other realities – which brings us back to the problem of online conspiracies.

In Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Dom Cobb uses a spinning tractricoid top that tells him if he is awake or still dreaming. You can think of the mechanisms I describe in Proof of X as social media’s equivalent of the spinning top. As influencers rent grounded private jets to pretend living a billionaire lifestyle, social networks introduce new proof-of-work hurdles to make sure our status games remain grounded in truth. Proof of reality.

It feels like some of the new virtual realities we have created need more than that. A kill switch that automatically brings us back to base reality.

So if you have reached this point of my essay, perhaps now would be a good time to close your browser window and enjoy real life. Or at least the closest simulation you have thereof.

Thanks to Aaron Z. Lewis, Jan König and Max Cutler for reading drafts of this post. If you have thoughts on this essay, please leave them here.