The Dark Side of Property – by J.K. Lund – Risk+Progress

Let’s take a journey to the dark side. The Tragedy of the Commons is a well-known problem whereby the lack of clear ownership rights stifles investment. Almost unknown, however, is its twin sister: The Tragedy of the Anticommons. The anticommons tell us what happens when property rights go too far. If we understand the anticommons, the ‘dark side’ of property, perhaps we can illuminate a possible middle path between private and common property. This middle way may enhance growth, human opportunity, and progress.

The Tragedy of the Commons

The great Aristotle was among the first to describe the problem that we now know as the Tragedy of the Commons. He said, “That which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it…each thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest. One of the classic examples of this problem can be found in overfishing of bodies of water.

Imagine a lake that is fished by local fishermen who sell their catch for profit. It is rational for each fisherman to catch as many fish as possible to maximize their own welfare. Absent ownership rights, many flock to fish the lake and reap their fortunes. Inevitably, the lake will eventually be depleted of fish; everyone loses in the long run. Collective ownership breeds overuse due to poor investment in the asset.

Over the centuries, human societies have developed complex workarounds to mitigate this problem. These solutions fall into two main camps: regulation and privatization. To solve the overfishing problem, for example, the government can step in, regulating who may fish, what kinds of fish they can keep, what quantity they may keep…etc. The problem, as I often discuss, is that bureaucrats don’t always have the best interests of society in mind.

As a consequence, the other solution, privatization, has become more popular. By dividing up ownership of the commons, each owner will have the proper incentive to invest in their respective property. In this case, they will take care to not overfish, because doing so would create future losses. Ownership breeds self-regulation and investment; keeping the lake flush with fish.

But many take this to a logical extreme: If privatization is good, more privatization and more property rights are always better. This is not necessarily the case. More privatization and fragmentation come at their own cost: The Tragedy of the Anticommons.

The Tragedy of the Anti-commons

The concept of the anticommons is, as Michael Heller notes, so foreign to us that we lack the proper lexicon to describe it. While the Tragedy of the Commons results in the overuse of resources, The Tragedy of the Anti-commons results in the underuse of resources. There is a kind of asymmetry here; it’s easier to “see” the overuse of resources than it is to “see” underuse. Hence, the anticommons might be thought of as the ‘dark side’ of property rights that are hidden from view.

We can best illustrate this concept by returning to another classic Tragedy of the Commons example. While sheep grazing on the commons will inevitably eat all of the grasses, leaving them hungry from overuse, privatizing that same field down to the square inch would be equally harmful. With only a square inch of feeding area per owner, the grasses overgrow because it’s not worth the time to herd sheep to such a small plot. The anticommons is too privatized, too fragmented to be of any use. Again, everyone loses.

The anticommons problem is prominently found in real estate when property is divided up between many owners. In the United States, for example, air travel volume tripled from 1975 to 2013. How many new airports were built to handle that traffic? Just one. Why? Well, among other reasons, airports require large tracts of land to accommodate terminals and runways. This land has to be purchased from local landowners, each of whom has every incentive to hold out for the highest possible bid, hoping to extract as much as they can from the airport developer. This is known as the “hold-out” problem.

This is the same problem, as I discussed here, that plagues patents. Patents are legal (if temporary) monopolies on ideas, that’s why we call it “intellectual property.” This is important because it gives inventors incentives to invest in their ideas, improve them, and market them. The downside, of course, is that patents also enable owners to exclude others from using that idea, preventing competition, and restricting those who might use that idea in better ways (allocative efficiency). This often results in “patent thickets” where new innovations are blocked by the high cost of securing necessary underlying patents, each trying to hold out for the highest possible royalty they can extract.

The Property Spectrum

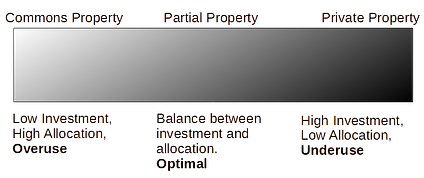

As these examples illustrate, there is a kind of “spectrum” of optimal property rights. No ownership results in high allocative efficiency (anyone can use the property) but low investment incentives, resulting in overuse. When ownership rights are too strong, however, investment incentives are high but allocative efficiency is low, so the property is not used in the most efficient ways. In both extremes, the end result is not optimal: the airport isn’t built, the sheep starve, and the fish don’t reach your dinner plate.

The optimal outcome for human civilization may be to recognize that property rights are not binary and exist across a continuum. That is, the best property is not commonly owned or privately owned, but rather a hybrid of both, or as Eric A. Posner and E. Glen Weyl call it, Partial Ownership. Their solution is to balance the tradeoffs between investment and allocative efficiency, between too much and too little ownership.

The easiest means of doing this, they argue, is to place a Harberger Tax on property. In Harberger taxation, property owners self-assess the value of their property at regular intervals (probably once a year), and pay an annual tax on that value. One might think of this as a kind of “rental fee” for property use.

Astute readers will correctly realize that property owners will assess the value very low to minimize their tax burden. That is why Harbeger Taxes come with a second requirement: anyone can purchase the asset at any time at the self-assessed value. The combined desire to minimize their tax burden but also get the highest possible value from property at sale, forces an honest valuation.

Glen Weyl and Anthony Lee Zhang find that the optimal tax rate depends on the category or type of property, but for most goods, a 5-10 percent rate appears sufficient. With this simple system, we can get 70-90 percent of the maximum possible allocative efficiency at only a modest 10-20 percent cost in investment efficiency.

Practical Application

In practice, owners would register their property in some kind of central digital registry, perhaps accessed via an app on their phone. They would self-assess the value of the property, either on their own or with the assistance of algorithms. They would pay an annual tax, or usage fee, on that value. New digital technology, including decentralized blockchain and Ethereum, makes such a registry possible without any central governing authority.

The key is that all “owners” must be ready to part with their property at any time because anyone could buy it. The airport developer, for example, could open up the app and buy the land/homes that they need for a new runway with a few presses of a touchscreen. There is no need for lengthy court battles, expensive holdouts, or government intervention. With this system, everyone gets a fair value for their property and the optimal outcome is realized.

We needn’t jump right into a 5-10% tax rate either, even a small tax of just 2.5% percent on property would significantly improve social welfare. Because a property can be purchased at a fair value without the “holdout problem” allocative efficiency is dramatically improved. At the same time, the tax itself is not too high so as to completely deter investment. Using our prior examples, the airport gets built, the sheep are full, and the fish are back on the table…but at a greatly reduced cost in terms of time and money.

Indeed, this all may sound a bit familiar to regular readers of Risk+Progress. I have frequently expounded upon the merits of Land Values Taxes as a superior source of government revenue that enhances growth and human opportunity. In some respects, Harberger Taxation functions similarly. But Harberger taxation could be applied much more broadly than on land values. Indeed, I have also suggested we could tax intellectual property this way. Some other relatively “easy” targets for Harberger Taxation include intangible works like artwork, broadband spectrums, but also real estate, and automobiles.

As with our discussion on Land Value Taxes, this then creates a question of what to do with this new revenue. The obvious answer is to redistribute the money back to the people in the form of a Citizen Dividend or UBI. This would partially offset the negative effects of the tax. When the offset is combined with the net utility that partial ownership creates, social welfare would be dramatically improved.

The Fuzzy Nature of Property

Now, it is easy to imagine that most people will be uncomfortable with the concept of partially owned property. We naturally conceptualize property rights as black or white; you either own something or you don’t. But this is a dramatic oversimplification of property rights as they currently exist. We already live in a world where property rights are not absolute; property is inherently a fuzzy concept.

You might own land but easements still restrict where you can build on it. Zoning might further limit what you can build on it. You may own a home, but the government can, in some cases, seize it via eminent domain. Intellectual property expires after a set number of years, and because it is intangible, the boundaries around those rights are not clearly delineated; a subject of many court battles.

Again going back to our airport example, the emergence of air travel in the 20th Century created a new problem: the right to three-dimensional space. Conceivably, landowners’ property rights extend three-dimensionally from their tract of land out into the sky indefinitely. Governments around the world, however, restricted that right by limiting the height of property rights, enabling planes to fly through them. Barely anyone noticed.

The Grey Zone

This is all to say that property is a fuzzy concept, a social construct that we humans have created, but a very important one. The unsung goal of property rights is to maximize human welfare; to give incentives for owners to invest in that property. We want our land to produce more food for the population, we want inventors to develop new innovations that make our lives better, and we want our cities to grow and provide jobs and opportunities. But private property rights come at the cost of allocative efficiency; the hidden dark of property.

To the extent that acknowledging this dark side enables us to improve upon property as a concept, to find a middle path that achieves the overarching goals of continued human progress, we should do so.