Suddenly, We Don’t Have Enough People

Just a generation or so ago, a book entitled The Population Bomb, by Paul Ehrlich, sold millions of copies, continuing a long tradition of Malthusian doomsday forecasts. Ehrlich predicted that the world would soon be overpopulated, resulting in mass starvation and death. But the dire predictions did not come to pass. Instead, we face a new and greatly underappreciated risk: population collapse.

Malthulsian Doomdaying

There is a long history of Malthusian doomsdaying. The term itself is derived from the name of Thomas Robert Malthus, who at the beginning of the 19th century, famously theorized that since the population grew geometrically while food output grew linearly, mass starvation was an inevitable outcome for much of humanity.

Malthus made this prediction at a time when the population had just crossed 1 billion. Ehrlich’s book was released in 1968, by which time the population had more than tripled, yet no worldwide famines materialized. On the contrary, the global population has since more than doubled again, to some 8 billion people. Meanwhile, the global incidence of hunger and the frequency and severity of famines has declined dramatically.

Malthusian reasoning appears sound enough, so why were these forecasts so wrong? There are a number of factors to consider, but the first among them is that Malthusians missed the mark on fertility, or the number of children born per woman. Instead of remaining constant, it steadily declined as countries developed and living standards improved.

In times past, it was accepted that a large fraction of children would not live past the age of five. Families preferred to have many children as a kind of “insurance” for their old age. But economic/technological development greatly reduced child mortality rates worldwide. Meanwhile, growing opportunities for women in the workforce raised the opportunity cost of having children.

As a consequence, the global fertility rate peaked around 1965, at just over 5 children per woman. Since then, it has been in steady decline and is now down to just 2.3. Note, a fertility rate of 2.1 is considered to be the minimum threshold that separates a growing population from a shrinking one. This means that, when taken as a whole, humanity now stands on the precipice of a population cliff.

Malthusians also missed the mark on technology. They incorrectly assumed that agricultural technology would remain static when in reality, new ideas would greatly increase output per hectare of land. In fact, just as Elhrich’s books hit the shelves, the so-called “Green Revolution” swept through much of the developing world. This revolution kickstarted a dramatic increase in global food output.

While we should celebrate the arrival of new technologies that saved countless lives, a caveat is in order. Much of the food produced, while greater in quantity/calories, is comparatively deficient in nutritional value, something that many fail to acknowledge. For a discussion on this, see my article below:

Due to declining fertility rates, the world population is now expected to level off around 10-11 billion people, before beginning a steady march downward. Instead of runaway growth, or a population “bomb,” already around half of the world’s population lives in countries with fertility rates below replacement level. Overpopulation is now less a concern than the emergence of an “empty planet.”

A New Stage of Demographics

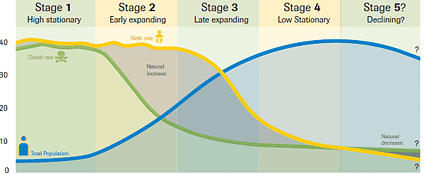

Demographers have identified four stages of demographic development. Stage 1 describes societies with high birth and death rates, keeping the population largely static at a low level. This describes humanity for most of its history. Since most people are children, the “dependency ratio” (ratio of people who can work to those who cannot) is relatively high.

New lifesaving technology and better living standards, such as those seen at the beginning of the industrial revolution, kickstarted Stage 2. In this period, death rates fall while birth rates remain elevated. Thus, the population soars upward.

Society reacts a generation or so later, with couples having fewer children in Stage 3 of the cycle. This gives rise to what is often called a “demographic dividend” where there are many working-age people relative to children and the elderly. The demographic dividend lends itself to higher economic productivity and faster innovation. Much of the world was benefitting from this “dividend” in the 20th Century.

But now many countries are entering Stage 4. In Stage 4, births continue to decline while the population rapidly ages, throwing the dependency ratio back in reverse, except this time, with more elderly than children. Exactly what happens from there is unknown, but most forecast shrinking and aging populations going forward into “Stage 5.”

The Impact of a Greying World

From a financial perspective, the above trends are troubling. Global pension systems like Social Security were designed under the assumption that couples would continue having children at the same rate as previous generations. Thus, there would be enough working-age citizens to support retirees. We now know that this is not the case.

The kneejerk reaction, as we are seeing in discussions in the US and elsewhere, is to raise taxes on the young to fund depleted pensions. But couples frequently cite financial considerations as the primary reason for having few children. Thus, raising taxes further threatens to exacerbate the fertility problem down the line.

See my essay below on one potential avenue for solving pension shortages here:

In addition, from an economic perspective, remember that growth is largely a function of improved labor output. Thus, as the labor force shrinks, labor productivity needs to rise much faster for growth rates to remain stable. A shrinking labor force makes growth all but impossible absent significant technological advancement.

By definition, technology allows us to do more with less. Would not armies of AI agents be able to replace the lost workforce and keep labor productivity growing? Maybe, maybe not. The problem is that a shrinking/greying population would also depress innovation at the same time.

Lessons from Tasmania

Around 12,000 years ago, rising sea levels, submerged the land bridge that connected Australia with Tasmania. The native population of Tasmania was cut off from the rest of Aboriginal Australia, an event that gives us insight into what happens when populations become isolated and smaller in size.

The archeological record in Tasmania reveals that the frequency and variety of bone tools steadily declined before disappearing completely. Tasmanians, once technologically equivalent to their brethren in the rest of the continent, slowly slid backward.

Ideas and what we call “technology” are nonrivalrous, that is, an idea can be consumed by one without reducing its availability to others. A larger population can simply create more ideas, it can iterate faster, and with more people, labor can better specialize. This is particularly and especially true if that society is in connection with other large civilizations from which it can absorb more ideas.

A small and isolated population simply cannot generate as many new ideas and, with time, may actually lose the technology it once had. A shrinking population, ceteris paribus, should translate into a slower pace of innovation, as well as slower (if not stagnant) economic growth.

But it may not require a shrinking population to stunt innovation; an aging one alone will do. Younger people have more of what psychologists call “fluid intelligence,” or an ability to come up with truly novel ideas. Older people have more of what is known as “crystallized intelligence,” which allows for more incremental solutions to problems that are built upon past knowledge.

Both forms of intelligence are important and largely complementary. A study by Mary Kaltenberg, Adam B. Jaffe, and Margie E. Lachman analyzed millions of patents filed over 40 years for disruptiveness. They found that although the raw patent productivity of researchers peaked around 40 years of age, truly disruptive work was done by the youngest inventors.

Since incremental progress is ultimately tied to disruptive innovation that came before it, this fact doesn’t portend well for an aging cohort of scientists. Indeed, by looking at Japan, arguably the front-runner of global depopulation and aging, we can get a sense of what this future looks like. In 2010, Japanese inventors led the patent world in 35 key global industries, but by 2021 Japan led in only three.

In another analysis by the London School of Economics’ Centre for Economic Performance, it is noted that Japan’s contribution to more novel industries, from blockchain to genome editing, has nearly evaporated. Japan has fallen behind the US in many areas, despiting low birthrates in the latter as well. The US, crucially, benefits from hefty inward immigration that Japan does not.

Populism and Progress

Finally, while we are only getting our very first glimpses of the political ramifications of depopulation, they too appear to be dire. On a more granular level, once the population of a city or town begins to age and fall, something of a “death spiral” begins. Tax revenue falls, local businesses leave, and unemployment ensues. It should be of no surprise that these very same localities, in the words of Brink Lindsey, can become “hotbeds of authoritarian populism.”

One analysis by the Brookings Institution noted that about half of U.S. counties depopulated during the 2010s, and President Trump won a majority vote in a staggering 90 percent of them. This trend doesn’t appear to be limited to the U.S. Depopulation and rising unemployment in small localities could be key factors in the rise of authoritarian populist movements around the world.

Thus, the global fertility collapse presents something of a triple threat to human progress. First, depopulation creates economic and financial challenges. Second, it simultaneously threatens to dampen our innovative capability at a time when we need it most. But the third, the most pernicious consequence of depopulation may be the political element.

As people in dying towns see their way of life disappear, they yearn for nostalgic (and false) memories of how “great” things used to be. Fed by a media that enthusiastically reports everything in negative framing, authoritarian populists are more than happy to confidently promise a return to the “good old days.”

They promise to enact counterproductive protectionist policies to “keep the jobs here.” They promise bans on immigration favoring nativist groups. They promise to restrict the marketplace of ideas and a return to “traditional” values. Most importantly, however, they abhor the democratic process, which they see as a threat to their idyllic vision of how things “should” be.

The populists’ “solutions,” obviously, will only accelerate the rot of these small towns, and their policy prescriptions will ultimately spread the decay to the big cities, and to the nation at large. For this reason, we must guard against populist movements with great vigilance and fully engage pro-progress policies.