How to Build Products Quickly – Department of Product

Stripe’s self described operating cadence is ‘run’.

The CEO of Stripe even has a collection of short stories about projects that were built ahead of time, despite naysayers saying it wasn’t possible.

These wonderful little anecdotes include:

- The construction of the Eiffel Tower which took two years and two months

- The first iteration of Disneyland which was built in just 366 days

- The Empire State building which was started and finished within 410 days

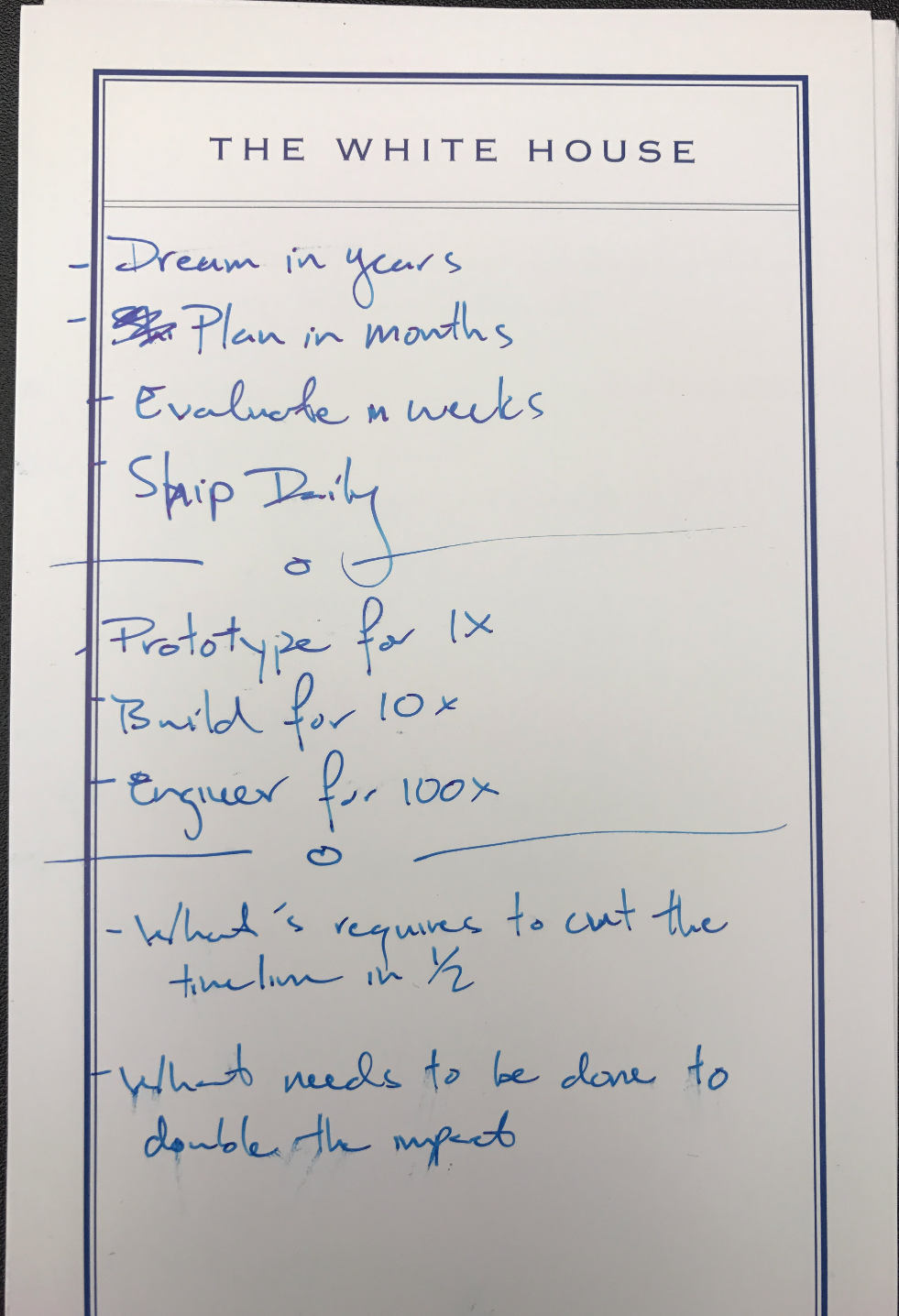

Former White House data scientist DJ Patil’s principles of execution include the question “What’s required to cut the timeline in ½?”.

If you’ve ever had the joys of working in both an early stage startup and a large corporation, you’ll understand the difference between a company with an operating cadence of ‘run’ and a company with an operating cadence of ‘stay afloat before the quicksand of corporate bureaucratic sludge kills you’.

In some instances, despite trying your best, the structures around you will inevitably slow you down. But let’s imagine you’re in the driving seat and you’re able to craft a set of rules that enable you to build products quickly. What would that look like? Let’s explore.

Make speed a product principle to be proud of

In my experience working at smaller startups and larger companies including eBay and major London-based banks, some product teams are actually quite reluctant to emphasise speed as a product principle. And I understand why.

An unhealthy focus on speed means that stakeholders fixate on it and the company culture becomes obsessed with it. Stakeholder expectations become oriented more around time and speed and less around value for users or achieving key results.

‘When will that be done?’

‘OK, so we can expect that next month?’

‘Why is this taking so long? Surely that’s a simple feature, it should be easy to build?’

‘Can we get a detailed timeline on that please?’

‘Maybe the best thing to do is to plan out the entire year in a detailed plan, with release dates for everything so that we have complete clarity.’

That’s why teams are reluctant to place too much emphasis on speed. Because it feels like it undermines the entire point of building products: to add value to users.

In some cases, moving too quickly will hinder your product’s chances of success. Theranos wasn’t ready for showtime but the company ploughed ahead regardless.

Despite all that, speed is important.

If you spend too much time fixating on processes or textbook product development theories, you’re not shipping stuff to customers. That’s not to say process and development theories are irrelevant (they’re not) – it’s just healthy to know when to shift focus from theory to practice.

Speed vs. lack of focus; they’re not the same

When you mention speed to product managers or product teams, one of the reasons many teams are so reluctant to embrace it is because the word ‘speed’ conjures images of the CEO or execs chopping and changing direction every day or making ridiculous requests out of the blue.

Acting quickly doesn’t mean constantly changing direction or switching your focus from one priority to another; that’s a symptom of a lack of focus. Speed requires focus and discipline.

Why speed matters

Trends are shifting. Competitors are beating you to the market. You’re losing customers who can’t wait for a critical feature any more. Product market fit is as elusive as it ever was.

These are some of the reasons speed matters. And as a product person, you need to explain to your team why speed matters. If your team doesn’t know why they should act quickly, they won’t.

Choosing to act quickly as a product principle

Product principles are sets of guidelines or truths that product teams use to help with everyday product decisions. By adding speed-oriented principles to your product principles and ways of working, you’re formally agreeing as a team that speed is an important part of the way you get stuff done.

When you agree that speed is a product principle, you can start to explore other ways to optimise your team’s processes with speed in mind. More on this later.

Decentralise decision making

One of the quickest ways to slow down product teams is to burden them with slow decision making processes.

Sure, fundamental strategic decisions require deep thinking. But if there are decisions which don’t need a wider discussion, teams should be empowered to make them without any further input – and quickly.

Decision making responsibility

A simple, neat way to speed up the decision making is to try to loosely agree on the types of decisions that product teams need to make and to understand the rules of engagement.

If a decision doesn’t require input from anyone else, make it clear to teams that they are empowered to make that decision. This sounds obvious but many teams don’t fully realise the scope of their own decision making remit. Agreeing this up front as best as you possibly can will help.

Over time, teams will naturally understand the scope of decision making responsibility, but this is a useful way to structure the process for newly christened teams yet to embed themselves.

Example decisions

What front end framework shall we use?What should the button look like?

What should the first iteration include?What should the user journey look like?

What should we build and why?

Methods

- Agreement between team members

- If disagreement, final decision escalated to tech / product leads

- One on one decision making calls

- Escalated quickly if no decision is agreed

- Product council

- Quarterly product meeting

- Decision den

Motivate teams to do the work

Engineers, designers and other members of product teams won’t want to act quickly if they don’t understand why they should.

In my experience, motivating teams to get work done involves three critical parts:

- Explain why the work is important

- Explain how incredibly impactful the team’s contribution to the work is (how it fits to the wider strategy, goals etc)

- Explain why this team is trusted and is going to do it successfully

With a team motivated, you can then focus on why speed is important. This could be a pressure to achieve product market fit, pressure from investors or excessive user demand for a particular problem to be solved.

Jumping straight into speed and the desire to get things done quickly without taking the steps to first motivate a team won’t work.

Ask ‘could that be done faster’?

At all stages throughout the product development process, asking the question ‘could this be done faster?’ will help to move quickly.

Sometimes the answer is no. But if the answer is no, you can then probe further, to get to the root of what’s causing the slowness.

Example – building a customer service tool

We can’t launch the feature until customer service has a tool that enables them to handle queries relating to the new feature. The team who are capable of building this new tool are tied up with another project and won’t be available for another 2 months. This will delay the overall release by 3 months.

Could that be done faster?

No, because the team who are capable of building this feature are busy for the next 2 months.

OK, what can we do instead? Can the team pause what they’re doing to unblock us? Could we make do with a low fi customer service solution in the meantime?

Unless you probe to figure out the reasons why something can’t be done quicker, you won’t know whether you’re in a position to speed things up.

Hire fast workers

In this post by an ex-Facebook engineer, Erez Druk, he argues that some engineers are capable of working faster because they’ve learned to behave in that way:

Speed is a behavior, not a skill. That’s why you must hire for it and not hope to cultivate it (doesn’t work). This also implies firing engineers who are below your speed bar

Firing someone because they’re not up to speed does sound a little harsh (!), and I don’t agree that speed is a fixed behaviour that can’t be cultivated, but understanding speed as a behaviour is a critical point.

It is very difficult to transform someone who is used to working in a slow, sluggish environment where expectations are low into someone who is used to shipping every week, or multiple times a week.

I’ve worked with engineers who are hungry for more; they want to prove how quickly they can get stuff done and add value as quickly as possible. If speed is important for you and your business, hiring these 10x engineers can transform your output.

When hiring, take into consideration the environment from which your candidate has come from and understand their reasons for leaving. It might be that they worked in a slow environment, hate it and want a fast paced challenge. Or it may be that they prefer a slower paced environment. Speed isn’t for everyone.

Eliminate unnecessary process

When I speak to frustrated product managers and other product team members, one of their biggest frustrations is the burden of unnecessary process.

Unnecessary process often comes from Stalinist top down, centralised processes created by execs with too much time on their hands who fret that the teams aren’t productive enough.

Instead of focusing on important strategic decisions that could transform a company’s fortunes, execs fixate on process and demand that every team follows the same process so that they can measure story points and report back to their seniors how ‘productive’ the teams are where productivity is measured in Jira tickets and not value added or goals achieved.

Centralising team processes in an effort to speed up output often has the opposite effect. I once worked at a company where the CTO decided all product teams would follow the exact same process and cadence:

- Planning Mondays – the entire day would be dedicated to planning

- Sizing Thursdays – you guessed it, all sizing would take place on a Thursday

- 2 week sprints for all

- Demo Fridays – everyone would demo their sprint output at the end of the 2 week period

I understand why the CTO wanted to do this (to feel in control), but it was a disaster.

Choosing product development processes

What works for one team, won’t necessarily work for another. Allowing teams to decide their own ways of working (within specific parameters, of course), is usually the best way to achieve high performing teams.

Modern product development processes can include any of the following:

- Scrum – useful for predictability and keeping stakeholders who request everything all at once at bay

- Kanban – more flexible and fluid, can adapt to changing dynamics

- Scrumban – potentially the best of both worlds, allowing you to select elements from scrum and kanban

- Plan -> Build (iterate) -> Ship – much like a mini waterfall, engineers, PMs and designers work together to ship small features

- Shape up – 6 week cycles to build something meaningful

- GSD (Get Shit Done) – popularised by Shopify, similar to ShapeUp with 3 phases: think, explore, build

Each of these processes have their own pros and cons. And if speed is an important principle for you and your product, allowing individual teams to decide their own process will certainly help since it empowers them to decide what process works best for the skillsets, experience and roadmap priorities they have.

Invest heavily in DevOps

Shipping value regularly and quickly to customers is only possible if your engineers are physically capable of doing so.

A feature may be production ready but if it then takes 3 weekly release planning meetings and prioritisation process followed by a complex set of infrastructure changes to actually get the thing into production, the rest of the work done at a high speed before this doesn’t matter.

That’s why investing in DevOps is absolutely critical when speed is important.

In an ideal world, engineers should be able to ship their code to production in as few steps as possible – and as regularly as they wish – without having to navigate complex infrastructure problems. The most productive teams I’ve ever been part of were teams where all the engineers were able to ship code every day if they wanted to.

Working in an environment where continuous integration and continuous deployment are second nature means that:

- Customers get access to new forms of value quickly

- Engineers get motivated by seeing new customers use the new things they’ve shipped or the optimisations to existing features

- Stakeholders and execs feel the sense of momentum and trust the team to deliver because they see the teams delivering small chunks of value incrementally

Yes, there might be a steep pioneering tax to pay initially, but the pay off is ultimately worth it.

Automate as much as possible

Finally, on a very practical level, one way to ensure you and your team work as effectively, and quickly, as possible is to eliminate frequent tasks which could be automated to free up time.

No code tools now allow product teams to do this and as we’ve previously noted, some suggestions for automation could include:

- Saving and sharing important decisions to help speed up decision making

- Sending release notes to stakeholders and users

- Getting competitor activity alerts

- Getting customer feedback alerts

- Managing user research feedback

Sure, these are periphery when compared to fundamental, speed enhancing actions such as decentralised process design or motivated engineers, but eliminating lots of small barriers to progress can cumulatively reduce the burden of repetitive tasks and increase the overall speed of the team.

And if you automate enough of the menial tasks you don’t enjoy doing, maybe just maybe, you can enjoy a little down time with a cup of coffee and Slack notifications switched off.

Bringing it all together

Speed is a controversial topic. Building products quickly means finding a balance between getting stuff done as quickly as possible and not crafting an unhelpful culture where the entire company’s expectations are oriented around timelines.

This isn’t easy.

But if it means you ship value quicker, beat your competitors and learn to cut out unnecessary fluff from your process, it’s worth it.