Have you had that feeling of being several weeks into a project, and you find yourself wandering around, struggling to wrangle the scope back to what you thought it was when you started?

It’s an easy trap to fall into. It’s why I’m always thinking about ways to make targets smaller (or closer, if you’re thinking about real physical targets). The bigger and more ambitious you want to be with an objective, the more confidence you need to have that the objective is the right one. What happens often is we decide a project scope — a feature or product prototype we think has legs — but the scope gets bigger than the confidence that we’re right. A few weeks in and there’s hedging, backtracking, redefining. You realize you went down a blind alley that’s hard to double-back on.

I heard an interesting perspective on scopes and approaches to building. Think of the “scope” as the definition of what the project is seeking to do, and the approach as the how.

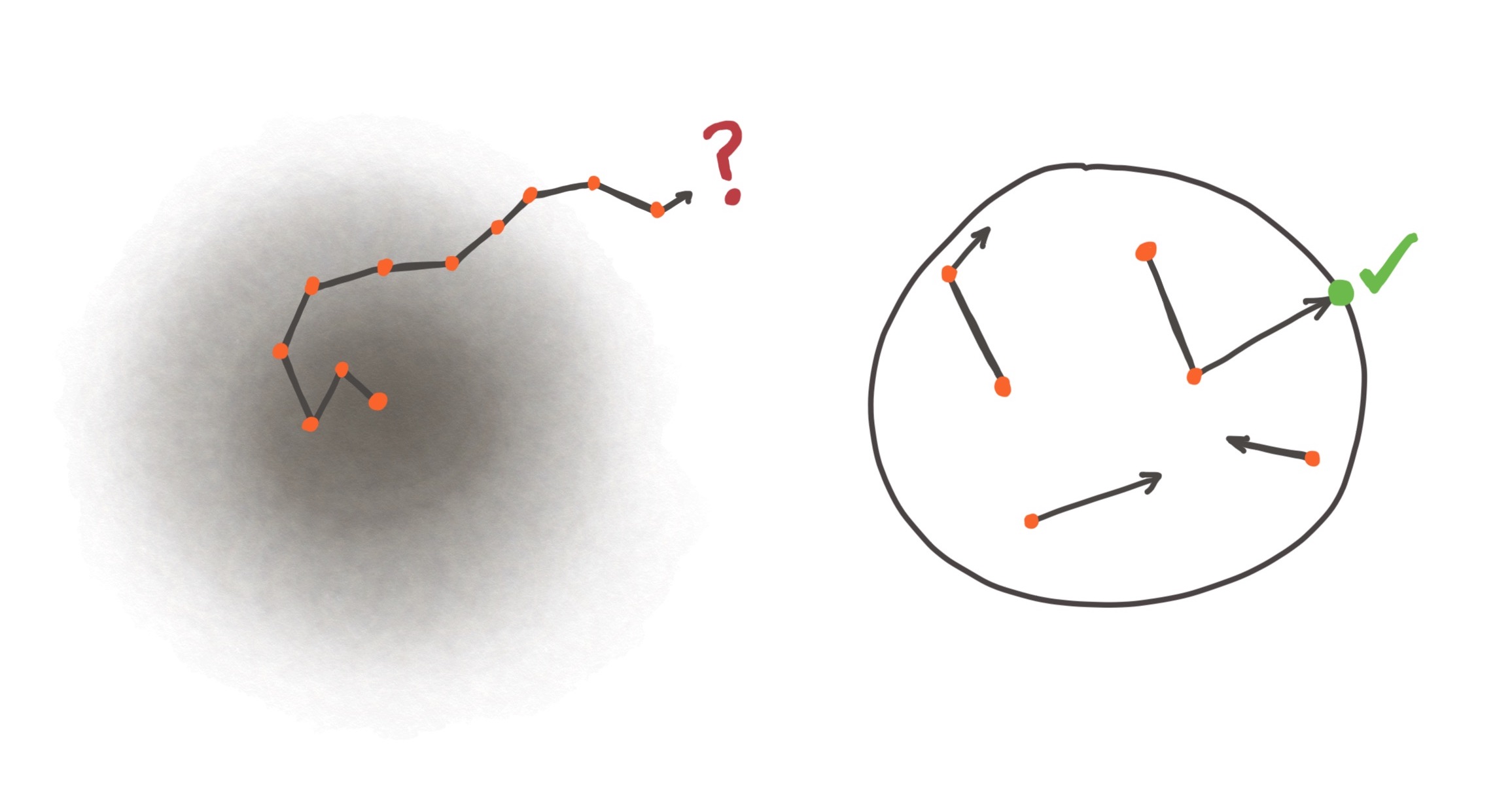

In an interview on David Perell’s podcast, Ryan Singer talked made a comparison between having a hard outer boundary for the work with soft requirements on approach, versus rigid and specific micro-steps, without a solid fence around it, an unclear or amorphous objective. In his words: “hard walls with a soft middle” or “hard middle with a soft wall”:

I’ve had this mental image that I haven’t been able to shake that’s working for me lately, which is what we’re doing in Shape Up. We have a very hard outer wall for the work. And we have a soft middle. So there’s a hard outer boundary perimeter — it’s very fixed, it’s going to be six weeks and we’re doing this, and this is in the project, and this is out of the project, and this is what this solution more or less. Clear hard outer boundaries. But then the middle is totally like “hey, you guys figure it out.” Right now what a lot of companies have is the opposite. They have a hard middle and a soft boundary. So what happens is they commit to this for the first two weeks, we’re going to build this and we’re going to build that, and we’re going to build that all these little things. And these become tickets or issues or very specific things that have to get done. And then what happens the next two weeks you say, okay, now we’re going to do this. You’re specifying exactly what should go in the middle, and it just keeps growing outward because there’s no firm boundary on the outside to contain it. So this is the the hard wall and the soft middle or the hard middle in the soft wall. I think our represent two very, very different approaches.

This requires trust in the product team to choose approach trade-offs wisely. If you encounter a library in use for the feature that’s heavily out of date, but the version update requires sweeping changes throughout the app, you’ll need to pick your battles. A team with fixations on particular steps (the “hard middle”) might decide too early that an adjacent feature needs rework. Before pulling up to a higher altitude to look at the entire forest, the team’s already hitched to a particular step.

Setting a hard edge with the soft middle sets what the field of play and game plan look like, but doesn’t prescribe for the team what plays to run. The opposite model has a team hung up on specific play calls, with no sense for how far there is to run, or even how large the field is in the first place. When you grant the team the freedom to make the tactical choices, everyone knows there’s some freedom, but it isn’t infinite. The team can explore and experiment to a point, but doesn’t have forever to mess around. If you choose to work in the Shape Up-style 6 week cycle, decision velocity on your approaches has to be pretty high to hit your targets.

Any creative work benefits from boundaries, from having constraints on what can be done. The writer is constrained by a deadline or word count. The artist is constrained by the canvas and medium. A product team should be constrained by a hard goal line in terms of time or objective, or preferably both.

Some of the best work I’ve ever been a part of happened when we chose particular things we weren’t going to do — when we intentionally blocked specific paths for ourselves for some cost/benefit/time balance. Boundaries allow us to focus on fewer possibilities and give greater useful, serious attention to fewer options. We can strongly consider 10 approaches rather than poorly considering 50 (or, even worse, becoming attached to a specific one before we’ve explored any others).

Premature marraige to specific tactics pins you to the ground at the time when you need some space to explore. Because you’ve locked yourself into a particular approach too early, it may require tons of effort and time to navigate from your starting point to the right end point. You may end up having to do gymnastics to make your particular decided-upon solution fit a problem you can find (a solution in search of a problem).

Hard edge, soft middle reminds me of a favorite philosophy from the sage Jeff Bezos, talking about Amazon’s aggressive, experimental, but intentional operating culture:

“Be stubborn on the vision, but flexible on the details.”

-

What you “need” to do is a dangerous trigger word. Almost always the perceived need is based on a particular understanding of trade-offs that could be misguided. One engineer’s need to recover some technical debt (while noble, of course) might be the opposite for CEO, who might be seeing a bigger picture existential need to the business. A thing is only “more needed” relative to something else. ↩

- 1