A fascinating design history of the filing cabinet

To be vertical is to be upright, positioned at a right angle to the horizon. Therefore, to think about the vertical is to consider the organization of space and to think about organization spatially. That is, verticality is a principle, a key attribute, frequently used to organize how objects are stored—a principle critical to the filing cabinet.

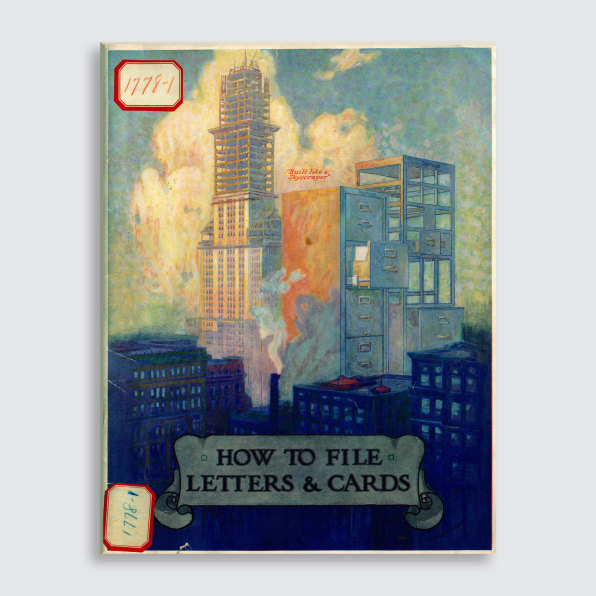

In the 1920s, scientific office management guru William Leffingwell understood the innovation and value of the filing cabinet in precisely these terms, arguing that height saved space—that is, it shifted the focus of storage space from the horizontal to the vertical. Verticality also locates the filing cabinet within the changes that marked the development of corporate capitalism at the turn of the twentieth century; it makes the filing cabinet available to a material history of efficiency. A somewhat simple example of this is the visual juxtaposition of the filing cabinet and the skyscraper in period advertising, most famously in Shaw-Walker’s “Built Like a Skyscraper” campaign. Such images promoted verticality as a historically specific remedy to the corporate articulation of spatial scarcity as a problem.

The filing cabinet emerged at the same time the skyscraper was becoming a cultural symbol that presented capitalism and modernity as distinctly American projects for the 20th century. As vertical structures, the skyscraper and the filing cabinet stacked discrete horizontal units (floors containing offices; drawers containing folders and papers). This stacking was intended to serve two main purposes: to reduce the structure’s horizontal footprint and to facilitate access to the units. Stacking, as opposed to mere piling, invoked order. In contrast to a pile, which leads to disorganization and congestion, the vertical was intended to provide structure, to organize through constraint. Through coercion, verticality would force activity and objects into designated spaces; the skyscraper as a vertical structure was a space organized to facilitate the flow of people and information.

Inside skyscrapers, changes in the design and use of desks in the early 20th century show how the office was rethought of as a site to facilitate the flow of paper. The emergence of a “flat-top” desk and the vertical filing cabinet offered a coordinated rethinking of the relationships between paper and work and between storage and retrieval. The efficiency-based focus on flow and movement made storage a particular kind of problem. Ideas about workflow positioned storage as a sedentary state in which papers would take up long-term residence in a cabinet or desk. As a leading proponent of office efficiency put it, “at best, any type of storage system is a passive agent in business.”

The increasingly complementary function of desks and filing cabinets emphasized the importance of the rethinking of offices as spaces organized to manage the movement of paper and facilitate access to information; this made storage primarily a temporal problem centered on retrieval. In this context, storage needed to take up as little space and as little time as possible. The solution was office equipment designed specifically to store paper on its long edge. This innovation was paired with a rethinking of the office desk as a “workbench.” In this new, early 20th-century version, “a desk should never be used for storage purposes but should serve as a means for the prompt dispatch of business.” The move from an “old-style storehouse model” to a modern flat-top desk foregrounded a change in the mode of storage— from personal to collective—as papers would ideally be moved from desks into filing cabinets.

The standard four-drawer cabinet in the early 20th century was about 51 to 52 inches high and 24 to 27 inches deep, although cabinet height was generally described in terms of drawers, not inches. Most early cabinets gained extra elevation from the addition of “sanitary legs”—sanitary because they allowed for cleaning underneath the cabinet and kept the contents of the lower drawers cleaner (as well as making them more accessible). To be clear, a clerk’s health was prioritized because it factored into her efficiency as a worker, not because of any concern for her general well-being. The relationship between efficiency and a clerk’s body also determined the depth of the cabinet. In presenting “maximum capacity” as one of the seven essentials of office equipment, Shaw-Walker explained that a drawer greater than 27 inches in depth risked turning filing from an “arm operation” into a “walking operation,” as the clerk would have to walk to the side of the drawer to access files at the rear.

The main selling point of early filing cabinets was modularity. Absent that label, in the first decades of the 20th century vertical filing cabinets went by a number of different names: unit, sectional, expandable, expansible. Office equipment companies intended the names to convey that offices could tailor filing cabinets to their specific needs, with the assumption that the businesses would grow, or at least produce more paper. Early advertising sought to communicate the ease with which filing cabinets could respond to the needs of a growing business. Recognizing this, most companies also made single-drawer units that could be the basis of expansion.

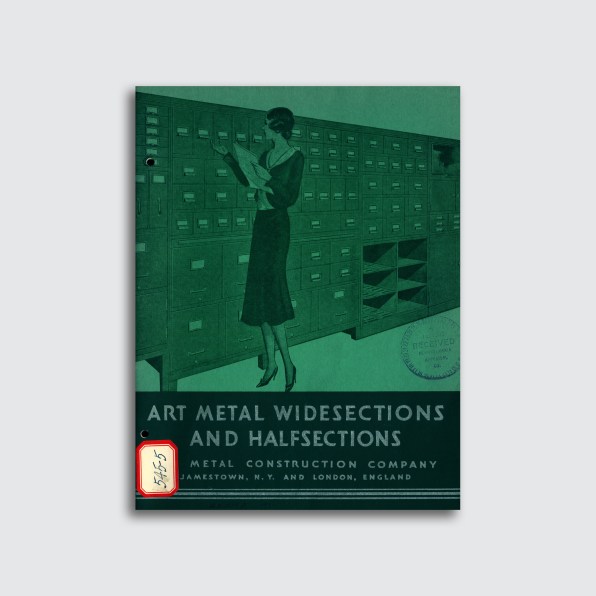

Side or top panels could be detached to facilitate expansion, with drawers added either side by side or stacked one on top of the other; the cabinets were designed to be connected with just a few bolts. Manufacturers claimed the resulting “battery” of cabinets would look like one seamless piece of furniture. Promotional materials for five-drawer filing cabinets (and for many four-drawer cabinets) accentuated the height of the women who operated them to deny the possibility that the height of cabinets could produce inefficiencies. In these advertisements female clerks were drawn (or photographed) standing tall with impeccable posture to accentuate not only the rectilinear design of the cabinets but also their height; if necessary, high heels elevated their bodies so they matched the additional height of the cabinet. From this height a tall, erect woman could easily “master” the filing cabinet as she gazed at the tabs inside a file drawer, while the catalog put her body on view for the assumed male reader.

At the level of office design, there was awareness that a filing cabinet was part of a larger assemblage. Experts suggested that regardless of where an office placed a cabinet, there should be at least three feet of aisle space to allow someone to walk by a clerk as she worked on a fully extended drawer. Filing cabinets could be used as partitions to demarcate departments in open-plan offices. The scarcity of natural or artificial light made cabinets a desirable alternative to floor-to-ceiling partitions, which tended to shut out both light and air. Therefore, the exterior of the cabinet, acting as a partition, divided office work in the same manner that the interior of the cabinet divided paper. A battery of cabinets could also provide a barrier between workers and customers, with the top used as a counter for waiting on customers or a table for clerks to work on.

The filing cabinet’s use as a counter or divider underscores the primary function of an office: to organize objects, workers, and tasks. It also emphasizes how important the idea of flow was in the reimagining of the early 20th-century office and the effect this had on the objects placed in office spaces. Along with desks intended for specialized tasks and the development of standard paper sizes (e.g., for typing and for index cards), filing cabinets acknowledged a move from “furniture” to “equipment.” Equipment (along with “office appliances”) represented a more functional and utilitarian approach to the office and office work.

Adapted with permission from The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information by Craig Robertson, published by University of Minnesota Press.