Mind the Platform Execution Gap

Leaders of software development organisations are under great pressure to

ensure that their employees spend their time on value-adding activities. One

way to achieve this is to use SaaS to outsource functionality that isn’t

part of their organisation’s core business. Another way is to consolidate

infrastructure capabilities required by many teams and services into a

digital platform (which might in turn rely upon SaaS and cloud providers).

Usually, internal platforms are curated combinations of internally developed

and externally procured capabilities.

Evan Bottcher has a great description of the key elements of a digital

platform:

A digital platform is a foundation of self-service APIs, tools,

services, knowledge and support which are arranged as a compelling

internal product.

The purpose of a developer productivity platform is to allow teams who

build end-user products concentrate on their core mission. Examples of

platform services include delivery services like pipeline infrastructure,

application services like Kubernetes clusters, operational services like

monitoring and security services like vulnerability scanning software.

An internal platform team will usually take tools and services offered by

cloud providers and other vendors and host, adapt or extend them to make

them conveniently available to their software developer colleagues. The

aim is not to reinvent commercially available functionality (the world does

not need another homegrown Kubernetes) but to bridge the gap between what

you can buy and what is really needed (your teams may appreciate a

simplified Kubernetes experience that takes advantage of assumptions about

your infrastructure and makes it easier to manage).

These services are often infrastructure-heavy, but we regard this

as an implementation detail. We take a broad view of platform where

we include any internally provided tooling that promotes

developer effectiveness.

Following Evan’s definition, we embrace documentation and support as vital

aspects of a platform. We believe that a what-it-is-for rather than a

how-it-is-made view of platform is preferable because offering platform

services to internal teams is an institutionalised approach to reducing

friction. It is incumbent upon platform engineers to keep an open mind

about the best way to reduce that friction. Some days that will be

provisioning infrastructure. Other days it might be making a build script

a little easier to use or facilitating a workshop to help a team to define

their SLOs.

When well executed, a platform strategy promises to reduce costs and

allow product development teams to focus on innovation. When it goes

wrong, problems with the platform are passed directly onto the entire

software development organisation. In our work with clients, we have

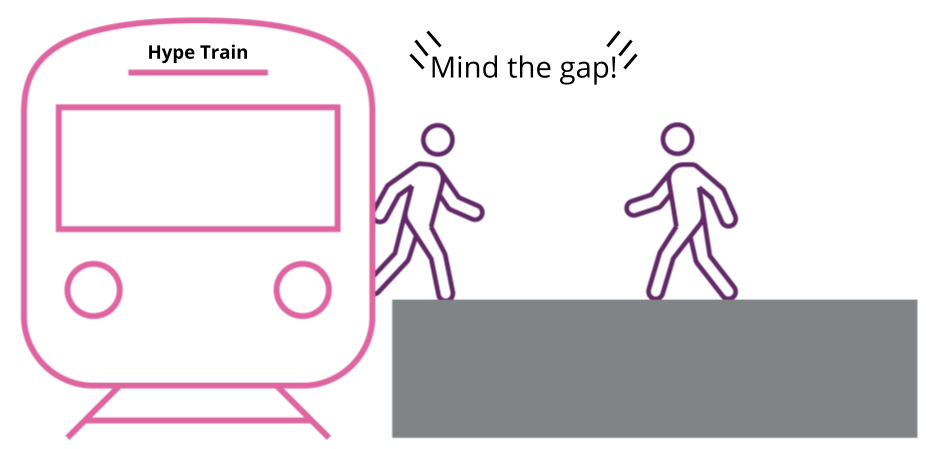

observed that there is a substantial amount of industry enthusiasm

(otherwise known as hype) around building internal platforms, but we also

see a potential execution gap that has to be navigated.

Please mind the gap between the hype train and the platform.

Building an effective platform and an organisation to support it is a

worthwhile but ambitious goal that takes greater maturity than directly

provisioning infrastructure for services. As with other ambitious technical

maneuvers, for example microservice architectures, there are foundational

competencies that are prerequisites for sustainable success. They do not all

have to be mature before you embark on a platform journey, but you must have

the appetite and resolve to develop them along the way, otherwise your

digital platform is unlikely to deliver a return on the substantial

investment you will put into it.

Business value

The decision to commit to an internal developer productivity platform

is an economic one. The argument in favour depends on efficiency, quality

and time-to-market benefits exceeding the financial, talent and

opportunity costs incurred in its construction and evolution. If you can’t

articulate the business case for your platform, then you aren’t in a

position to responsibly adopt it. Your calculations must take into account

the capabilities of commercially available services because unless your

platform offers features, specificity to your context or convenience that

a commercial offering cannot, you may be better off leaving it to the

market and avoiding the maintenance burden – after all your platform

strategy depends upon reducing the amount of undifferentiated work, not

increasing it!

The decision to build a digital platform is only the beginning of your

responsibility to substantiate the business value of your digital

platform. The motivation for a platform strategy may be compelling at a

high level, but there are many fine-grained decisions involved in deciding

which features to offer and how to offer them. To complicate matters

further, the business justification for your features will shift over time

as the state of technology progresses, the needs of your organisation

evolve and cloud providers and other vendors release new and improved

offerings that compete with your homegrown solutions.

To deliver the promised value to your organisation, plan for a greater

proportion of continuous improvement versus product innovation than

end-user facing products. To keep the platform manageable and costs under

control, operability-related items must have a place of honour in the

backlog. Your users appreciate consistency, stability and dependability

over a stream of new features. Also, every product that you offer you must

some day deprecate in favour of a new product on the market, an internally

built successor or even devolving responsibility for the capability back

to your product development teams. Deprecation is a fundamental part of

the platform product lifecycle, and failure to consider it may undermine

the business benefits you hoped to gain by offering it in the first

place.

Product thinking

You must never forget that you are building products designed to

delight their customers – your product development teams. Anything that

prevents developers from smoothly using your platform, whether a flaw in

API usability or a gap in documentation, is a threat to the successful

realisation of the business value of the platform. Prioritise developer

experience – a product that no one uses is not a successful product, no

matter its technical merits. In order to achieve return on investment for

your internal platform, your product development teams need to use it and

use it well. For that to happen, they need to appreciate it, understand it

and be aware of its features. As Max Griffiths describes in his article

on Infrastructure as Product,

platform products require customer empathy, product ownership and

intelligent measurement, just like other kinds of product.

One advantage of internal products is that you have users that are

highly invested in your products’ evolution and success. Like any group of

customers, your colleagues will be a mixture of the skeptical, the neutral

and the enthusiastic. Harnessing the enthusiasts and helping them to

become early adopters and champions of the platform will greatly benefit

perception of the platform in your organisation. Communicating your

roadmap, accepting feedback and harvesting experiences from your users

will contribute to your platform’s ongoing relevance. Luckily, you all

work for the same organisation, so you have rich communication channels

available. Internal platforms need marketing. It won’t look the same as

marketing a product to the public, but it’s marketing nonetheless.

Maintaining goodwill is key to adoption. So if you have any unavoidable

outages, communicate them and perhaps adapt your plans to reduce impact on

your users. If something goes wrong and you have an outage (hint: you

will) then apology and transparency will reassure them. Resist the

temptation to rely on managerial mandates as an adoption strategy. You may

have captive users, but compelling them to use products supposedly for

their own good does not foster a productive relationship.

Operational excellence

When you adopt an internal platform, you ask your product development

teams for a great deal of trust. Your platform is now a key dependency of

the systems your organisation uses to fulfill its function. Your

operational competence needs to be sufficient to justify that trust.

This means that your platform teams need to have a sound grasp of the

fundamentals of software infrastructure, like networking, scaling and

disaster recovery. If your platform engineering teams have difficulty with

the underlying technology, they will not build robust products for your

product development teams. Furthermore, modern operational excellence

extends beyond infrastructure and into practices that ensure reliability.

The book Site Reliability

Engineering is a good account of the state of the art in this area.

If your platform organisation doesn’t have skills in SRE practices like

observability, monitoring and SLOs, not only are you at risk of breaking

the trust of your product teams, you are at risk of doing it and not

knowing that you did it.

Your platform organisation must also have the maturity to manage

incidents efficiently and to learn from them. Out-of-hours support,

alerting systems and blameless incident retrospectives should be a

priority. You may need to establish processes, modify wording on employer

contracts and budget for fair compensation to make this possible, as well

as make on-call a sufficiently pleasant

experience to encourage broad participation. It will also affect

your planning. When you need to make significant changes, for example

migrations, you need to invest in making them gracefully so as to minimise

downtime for your users.

Software engineering excellence

A platform organisation is not just an operations department, so it

needs more than operational capabilities. Even if you do not plan on

writing substantial custom applications, your scripts, templates and

configuration files will rapidly accumulate complexity. If you want to

retain the ability to quickly and safely change your platform, you need to

build it the right way.

Our favourite summary of software engineering excellence in an

infrastructure context are the three core practices of infrastructure as

code, as defined by Kief Morris in his book

Infrastructure as Code:

- Define everything as code

- Continuously test and deliver all work in progress

- Build small, simple pieces that you can change independently

If your organisation is able to consistently apply these practices,

it’s much more likely to be able to execute on your platform vision.

Without them, you may be able to get your infrastructure into a good state

at a point in time, but you will not be able to sustain the pace of

evolution your development teams’ changing needs will demand.

Using internal products places demands on product development teams

too. Good product development teams are aware of the service levels

offered by their dependencies, factor them into their own designs and use

engineering practices to mitigate those risks that could impact their

service level objectives. This is even more important when those

dependencies are provided internally, because no matter how high quality

your platform is, it is unlikely to reach the level of polish of a

commercial SaaS provider.

Healthy teams

Individual skill is important, but sustaining excellence over the long

term requires strong team-level disciplines. When your platform systems

are depended upon by the rest of the business, it’s not acceptable for the

expertise to maintain them to be held only by a few busy individuals. You

need autonomous teams with clear missions who avoid individual code or

system ownership. They must invest in knowledge sharing, documentation and

onboarding. A single person winning the lottery should never be a threat

to the viability of your platform.

To keep these platform engineering teams productive, their systems for

planning work need to be mature. They must have backlogs of items

described in terms of their value and have processes for prioritisation,

otherwise the urgent may overwhelm the important. Incidents and unplanned

work are inevitable, but if too much of the team’s time is consumed with

toil, then it will never have the capacity to invest in the improvement of

its products. Teams should not try to manage too many platform products at

once.

We find the idea of cognitive load, as discussed in Matthew Skelton and

Manuel Pais’s book Team Topologies,

a useful one for keeping teams’ missions manageable. If a team constantly

switches context between completely different tasks, then the cognitive

load is too great and, when this happens, not only will the team be less

capable to undertake their day to day work, but it will also be difficult

for new team members to gain the confidence they need to work on all the

systems.

Getting started

If you do not already have these capabilities in your organisation,

does that disqualify you from adopting a platform strategy? How, you might

ask, are you supposed to build these capabilities without lessons

obtainable only from experience?

The secret is not to compromise on the quality of your execution, but

to be modest in the scope of your ambition – at first. A platform

initiative, no matter how small, should produce business value, be guided

by product thinking, be implemented with operational and software

engineering excellence and be backed by a team structure that can sustain

the new platform service. Anything less than that, and the boost you hoped

to deliver is likely to become a drag that tarnishes the reputation of

your fledgling platform with developers in your organisation.

Small, focused platform services targeted at well-understood parts of

your technology estate have a lower degree of difficulty. They don’t let

you off the hook for considering platform from a holistic perspective, but

they let you get started and build from there. For example, providing a

logging cluster that can ease the operational burden on product teams and

improve visibility across services has clear business value that does not

require sophisticated financial modelling to establish. It still requires

product thinking to ensure that it serves its customers (does its

availability, freshness and search UI meet the needs of the developers?)

but that product thinking does not need to have the maturity of that

required to, for example, offer a unified developer portal. And it still

requires software engineering, operational skill and a healthy team to do

well, though not as much as to, for example, build an observability

sidecar for all your organisation’s microservices.

The first question to ask yourself is what is the smallest thing

[1] we can build that would help the product teams?

The second is how could we upgrade or migrate away from this when the time

comes? The state of the art is evolving rapidly and vendor lock-in is no

less painful because the vendor is your very own organisation. If

deprecating your platform service would require a painful transition over

years, it is probably time to go back to the drawing board and simplify

your product. You do not need to have a detailed calendar and a plethora

of substitute technologies ready to go, but factoring in a realistic

lifetime (three to five years) and architectural seams for replacing

solutions will force your designs to be simpler and more decoupled.

We recommend that adoption of your platform be voluntary. This supports

your platform strategy in two ways. Firstly, when product teams have the

ability to opt out of platform services, it encourages you to keep your

services loosely coupled, which will benefit the platform when the time

comes to launch a new generation of the service or to replace it with a

commercial offering. Secondly, when your platform organisation is

dependent on product teams’ appreciation of the platform’s benefits, it

puts a strong pressure on your platform organisation to keep customer

delight at the forefront of their minds. Mandatory migration to the

platform is a shortcut that has the long-term risk of eroding your team’s

product thinking discipline.

You may find a simple classification system useful to set expectations

about the maturity of new platform features, for example to indicate that

a new feature is in beta. You might want to associate SLOs and support

tiers with the maturity classification as an experimental feature needs not

to offer the same high availability as a core feature or your platform. It

may not, for example, require round the clock support. Once the feature is

promoted to full support, users of the platform can expect SLOs strong

enough for them to build mission critical components on top of, but before

then a less demanding set of expectations gives the platform team freedom

to experiment and to validate their assumptions about the product before

making a strong (and long-term) commitment to it.

If you are able to keep the above in mind, you will have an additional

advantage. Your platform teams will manage small portfolios of very

effective products. Their cognitive load will be small and their focus

will be able to stay on continuously reducing the development teams’ time

to market instead of just on keeping the lights on.

Conclusion

Digital platforms are portfolios of technical products. Like all

products, platforms generate value through use. With the right underlying

business justification, careful product management and effective technical

execution, digital platforms succeed by reducing cognitive load on product

development teams and accelerating an organisation’s innovation. Platforms

take considerable investment in terms of money, talent and opportunity

cost. They repay this investment by positively impacting product

development teams’ ability to quickly and efficiently develop high quality

customer-facing products.

Developing a digital platform is a strategic decision and not to be

taken lightly. Besides the direct financial considerations, digital

platforms also exert pressure on the relationships within your

organisation. Product developers’ have experienced the offerings of

commercial cloud providers and to live up to those raised expectations

platform engineering teams must be mature in both product management and

technical implementation. Product development teams also have to learn to

be good partners of your platform organisation and accept their share of

responsibility for the operation of their services.

Digital platforms are force multipliers, so there is a fine line

between developing a competitive advantage and introducing a significant

productivity blocker. The decisions you make along the product lifetime

will determine whether you walk on one side or the other. The good news is

that just like with every other kind of software development, if you start

small, empathise with your customers, learn from your successes (and your

failures) and keep your overall vision in mind, you have every chance of

success.

-

1:

“Thinnest viable platform” according to Team Topologies.