Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and society, broadly speaking. If you find the writing helpful, you can sign up if you haven’t already, share it with others, or subscribe.

I’m a Mets fan. Right at this moment, that’s not such a bad thing. Despite having up to 17 players on the injured list earlier this season, they’ve been in first place in their division for nearly two months. Over the past three decades, however, being a Mets fan has meant mostly disappointment and frustration, punctuated by rare moments of joy. Naturally, I’m bequeathing this legacy of emotional turmoil to my daughters.

But it’s not only the first place standing that makes this a tolerable, even enjoyable baseball season. It is also the once-in-a-lifetime performance that pitcher Jacob deGrom has been putting on. If you attend at all to the world of American sports, you may know that deGrom has been one of the best pitchers in baseball the past few years. He won consecutive Cy Young awards in 2018 and 2019. This season he is having a historically good run. I’ll spare you the statistics. If you peruse the top search results for “deGrom” on Twitter, and you’ll get a sampling of his accomplishments thus far.

It’s been a delight to watch him pitch. He combines remarkable physical skill and precision with uncanny mental focus and composure. He gets measurably better in higher pressure situations. On the mound, his lack of emotional expression lends him an almost robotic air. You get the point. The man is good, and his current stretch may very well be the best stretch by any pitcher ever. Oh, and he throws hard. Since the beginning of the pitch tracking era in 2008, deGrom has been the only starting pitcher to average 100 mph on his fastball for an entire game. He’s done it twice this year. He has also set the record for the most 100 mph pitches in a game.

Perhaps the most striking thing about deGrom’s velocity is that it has improved year after year. In 2016, his average fastball came in at 93.9 mph. In 2020, it was at 98.7. Thus far in 2021, he’s average 99.2 mph. This impressive improvement over time is especially notable given deGrom’s age. He turned 33 on June 19th. So how has he done it? One answer is that he has achieved machine-like efficiency with the mechanics of his delivery.

Here is a video produced by Tread Athletics, a baseball consulting firm focused on harnessing data to improve pitcher velocity. It’s an analysis of Jacob deGrom’s mechanics over the last few years during which his average velocity increased more than 5 mph.

The video presentation is about 50 minutes in length and relies on video archives of deGrom’s pitching career. As the presenter makes clear, they have no special access to deGrom and the analysis is undertaken with a view to gleaning lessons for the firm’s clientele. That said, it offers an interesting glimpse into the world of elite or would-be elite pitchers. Pretty much every aspect of their bodily motion is subject to measurement, analysis, and calibration. Consider, too, especially if you’ve not kept up with baseball analytics, the sheer volume of data available to measure a pitcher’s performance. Take a look, for example, at deGrom’s page at Baseball Savant or FanGraphs. Turns out that when you can track and measure every pitch and every swing, you can generate an absurd amount of analytical categories.

As I thought about deGrom’s mechanical precision, it seemed that baseball analytics offered an interesting vantage point from which to consider the nature of data-driven optimization that now structures so much of contemporary society. For example, the analytics trajectory that emerges circa 2008 with the deployment of increasingly precise and comprehensive data gathering tools also mirrors broader social trends. We can now measure and analyze dimensions of personal and social life that we wouldn’t even have thought to measure a decade or two ago. It was always theoretically possible for us to count our steps, but altogether impractical. Now we can have it done for us passively. Indeed, as most of us know all too well, all manner of information about us and our activities is now gathered passively, stored indefinitely, and put to useful, dubious, and dangerous ends. Aspiring pitchers may now be able to finely calibrate and optimize their bodily motions to increase their velocity, but it is another thing altogether for a corporation to similarly monitor and discipline the bodies of their employees for the sake of more efficient production.

It will be helpful, I think, for us to consider data-driven optimization in light of what the mid-20th century French polymath Jacques Ellul called la technique. Some of you will already be familiar with what Ellul meant by the term, but, if you’re encountering it for the first time, a bit of exposition is warranted. It was an expansive concept, which Ellul used to capture what he considered the tyrannical dominance of the drive for efficiency in modern society. Here is a helpful synopsis from James Fowler:

Ellul’s issue was not with technological machines but with a society necessarily caught up in efficient methodological techniques. Technology, then, is but an expression and by-product of the underlying reliance on technique, on the proceduralization whereby everything is organized and managed to function most efficiently, and directed toward the most expedient end of the highest productivity. Ellul’s own comprehensive definition is found in the preface of The Technological Society: “Technique is the totality of methods, rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.”

And here’s a bit more from Fowler’s discussion of what technique had become in the 20th century according to Ellul:

Technique became the defining force, the ultimate value, of a new social order in which efficiency was no longer an option but a necessity imposed on all human activity. Technique became universally totalitarian in modern society as rationalistic proceduralism imposed an artificial value system of measuring and organizing everything quantitatively rather than qualitatively.

The tendency remains, and, as Ellul predicted, it has only intensified. The power of digital computation—still nascent when Ellul published his best known work, The Technological Society—radically widened the scope of technique, understood as the drive toward efficiency in all realms of human experience. And, as it turns out, developments in the game of baseball illustrate the more general social patterns pretty well, and they may, in fact, present us with a few insights into la technique realized in the culture of optimization.

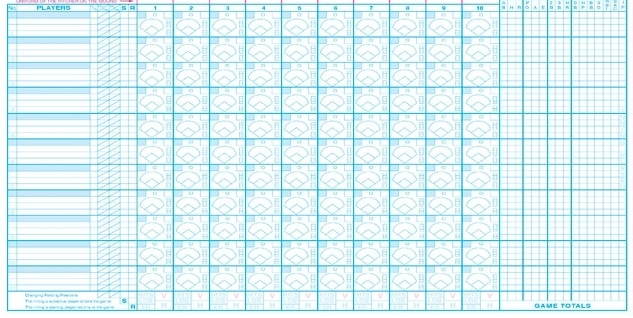

Baseball, of course, has always been a numbers game, at first characterized by traditional statistics based on analog records. The first box score, for example, is attributed to Henry Chadwick, who came up with it in 1858. The baseball scorebook (belwo) became the standard tool for recording at bats, hits, strikeouts, walks, runs, etc.

This simple tool supported the collection of a surprising amount of data. Most of this data told us what had happened in a game, and it required relatively straightforward calculations to yield useful information about player performance. A more sophisticated class of statistics was then made possible by computation. My sense, too, is that there was also a shift in what statistics could tell us about: from what has happened to what will happen, from documentation to prediction.

Here, for instance, is an interesting tidbit about Davey Johnson’s career-long fascination with harnessing the power of computation:

Before Bill James popularized sabermetrics, Davey Johnson used an IBM System/360 at team owner Jerold Hoffberger’s brewery to write a FORTRAN baseball computer simulation while playing for the Baltimore Orioles in the early 1970s. He used his results in an unsuccessful attempt to promote to his manager Earl Weaver the idea that he should bat second in the lineup. He wrote IBM BASIC programs to help him manage the Tidewater Tides, and after becoming manager of the New York Mets in 1984, he arranged for a team employee to write a dBASE II application to compile and store advanced metrics on team statistics.

Davey Johnson was a pioneer of a data-driven approach to the game enabled by modern computing that was later popularized by Billy Beane, the general manager of the Oakland A’s in the late 90s and early 2000s. Beane’s success in fielding a winning team on the cheap using advanced metrics was chronicled in Michael Lewis’s Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game (2003). Beane’s success, of course, meant that other teams would take note and follow suite. What was once a distinctive and idiosyncratic approach to the game became the dominant strategy. The consequences of this homogenizing tendency will be the first thing for us to consider, and, back in 2018, Alan Jacobs described the consequences in an essay lamenting the flattening of the game that followed the success of the sabermetric revolution.

Jacobs begins the essay by recalling his fascination with the Baltimore Orioles of the early 70s led by manager Earl Weaver. Interestingly, this was the same team Davey Johnson played for when he was fiddling with FORTRAN simulations. Weaver’s distinctive approach to the game focused on the most efficient way to score runs was soon validated by Bill James’s statistical analysis in the late 70s and Billy Beane’s success with the A’s. But here a paradox emerges: Jacobs argues that “strangely enough, baseball was better when we knew less about the most effective way to play it.” In Jacobs’s view, when everyone knows the most efficient way to play the game, the game as a whole loses its color and variety.

Jacobs’s goes on to explain how this played out:

Coaches used to place a lot of emphasis on teaching batters how to hit the ball to the opposite field, at least sometimes. But sabermetrics has shown that batters get more hits, and more extra-base hits, if they pull the ball. In turn, the increased dominance of pull-hitting has led defenses to employ shifts that place fielders in the most likely paths of balls hit by any given batter. And then batters have responded to these shifts by realizing that it doesn’t matter where the fielders are if you hit the ball out of the park. So: more and more batters swinging for the fences, hitting more home runs than ever, and accepting historically high levels of strikeouts as just the inevitable collateral damage.

And, as Jacobs goes on to emphasize, “coaches and players understand the percentages better than they ever have in the history of the game, and are acting accordingly. All of these changes I have traced are eminently rational.”

“So you can’t blame anyone for the way the game has developed,” Jacobs concludes. “It has become more rational, with a better command of the laws of probability, and stricter, more rigorous canons of efficiency.”

It’s worth pausing to consider wherein the purported rationality lies. It is the logic of competition. Within the sporting world, of course, the point is to win, and to do so in a way that can be clearly determined quantitatively. There are no grounds for anyone to ask a manager or a player to pursue a strategy that will diminish their competitive edge. Most of life, however, is not a game with quantifiable outcomes, and probably shouldn’t be treated as such. However, the triumph of technique in Ellul’s sense encourages the competitive mode of experience. Indeed, quantification itself invites it. This dynamic can be put to beneficial use, and, in clearly delineated circumstances, is perfectly appropriate. But applied uncritically and indiscriminately or even nefariously (see e.g. social media metrics) it can introduce destructive tendencies and eclipse qualitative or otherwise unquantifiable values. Generally speaking, quantification and the logic of optimization which it encourages tend to transform our field of experience into points of aggression, as the sociologist Hartmut Rosa has aptly put it. Data-driven optimization is, in this sense, a way of perceiving the world. And what may matter most about this is not necessarily what it allows us to see, but it keeps us from perceiving: in short, all that cannot be quantified or measured.

On an earlier occasion, Jacobs’s analysis also recalled a distinction drawn by one philosopher between what is correct and what is true. What is correct may fall short of truth because it is partial or inadequate, and may for that reason be, in fact, misleading. It seemed to me that we might, in similar fashion, draw a distinction between what is right and what is good. It was right for the Baltimore Orioles in the 70s and the A’s in the early 2000’s to optimize their team strategies and tactics as they did. Moreover, it is right (meaning rational and in keeping with the competitive nature of the sport) for all other teams to do so. It is not, however, good for baseball that they do so, or so Jacobs and others who take his view of things would argue.

But is the game, taken as a whole, really worse off? Anecdotally, I encounter frequent complaints from diverse quarters about the homogenous character of the game. And it’s worth noting that there are also perennial anxieties about the popularity of the game among younger fans unrelated to the fallout of an analytics intensive approach to the game. But there are, I’m sure, many fans who are untroubled by any of this. So, is Jacobs right to say that baseball was better when we knew less about it? And here we are at the crux of the issue from another angle: how is the goodness of the game measured and accounted for? Or, more to the point, can the goodness of the game be measured? If not, then in what would the goodness of the game consist? And, an equally interesting question, why might we assume or want it to be the case that good can be adequately quantified? My point in raising these questions, of course, is that we should ask them in relation to things other than baseball.

As it turns out, Jacobs’s analysis in the piece I’ve been referencing reminded me of a paragraph he had posted on his blog a few years prior from Claude Levi-Strauss’s memoir, Tristes Tropiques:

In Martinique, I had visited rustic and neglected rum-distilleries where the equipment and the methods used had not changed since the eighteenth century. In Puerto Rico, on the other hand, in the factories of the company which enjoys a virtual monopoly over the whole of the sugar production, I was faced by a display of white enamel tanks and chromium piping. Yet the various kinds of Martinique rum, as I tasted them in front of ancient wooden vats thickly encrusted with waste matter, were mellow and scented, whereas those of Puerto Rico are coarse and harsh. We may suppose, then, that the subtlety of the Martinique rums is dependent on impurities the continuance of which is encouraged by the archaic method of production. To me, this contrast illustrates the paradox of civilization: its charms are due essentially to the various residues it carries along with it, although this does not absolve us of the obligation to purify the stream. By being doubly in the right, we are admitting our mistake. We are right to be rational and to try to increase our production and so keep manufacturing costs down. But we are also right to cherish those very imperfections we are endeavouring to eliminate. Social life consists in destroying that which gives it its savour.

It’s not altogether obvious to me that social life must consist in destroying that which gives it its savor. I suppose much depends on what exactly is entailed by “purifying the stream,” as Levi-Strauss puts it. As Ellul saw it, technique colonized realms of life to which it did not properly belong. The key, then, is to recognize where and when it is appropriate to allow technique (or quantification or optimization) a place and where and when it would be good to circumscribe its scope. In order to do so we must have before us a clear sense of the good we seek. But, as Ellul warned, technique becomes a problem precisely when it becomes and end in itself. This may happen because we ourselves lose sight of the ends we were originally seeking or because the focus on technique itself gradually blinds us to those ends. It would seem that when a framework within which questions of the good can be meaningfully taken up is unavailable, then quantification rushes in to fill the axial vacuum. In his own fine post on baseball and optimization a couple of years back, Rob Horning cited Melissa Gregg who observed that “personal productivity is an epistemology without an ontology, a framework for knowing what to do in the absence of a guiding principle for doing it.”

So as more and more of our lives become subject to regimes of optimization, we should remember the limits of quantification and strive to see what we cannot measure. And because we may need a little help toward that end, I’ll wrap us up by commending a children’s book to you, The Little Prince.

“Good morning,” said the little prince.

“Good morning,” said the merchant.

This was a merchant who sold pills that had been invented to quench thirst. You need only swallow one pill a week, and you would feel no need for anything to drink.

“Why are you selling those?” asked the little prince.

“Because they save a tremendous amount of time,” said the merchant. “Computations have been made by experts. With these pills, you save fifty-three minutes in every week.”

“And what do I do with those fifty-three minutes?”

“Anything you like …”

“As for me,” said the little prince to himself, “if I had fifty-three minutes to spend as I liked, I should walk at my leisure toward a spring of fresh water.”

You should read the whole thing someday if you’ve never done so. And maybe glance at this old poem by Wendell Berry.