Maximizing Developer Effectiveness

I often help engineering organizations that are in the midst of a

transformation. This is typically both a technology transformation and a

cultural transformation. For example, these organizations might be attempting

to break a core monolithic system into microservices, so that they can have

independent teams and adopt a DevOps approach. They also might want to improve

their agile and product techniques to respond faster to feedback and signals

in the market.

Over and over, these efforts have failed at some point in the

transformation journey. Managers are unhappy with delays and budget overruns,

while technologists struggle to resolve roadblocks from every direction.

Productivity is too low. The teams are paralyzed with a myriad of

dependencies, cognitive overload, and a lack of knowledge in the new

tools/processes. The promises that were made to executive leadership about the

latest technology are not coming to fruition quickly enough.

There is a stark contrast of approach between

companies that have high and low developer effectiveness

When we look into these scenarios, a primary reason for the problems is

that the engineering organization has neglected to provide developers with an

effective working environment. While transforming, they have introduced too

many new processes, too many new tools and new technologies, which has led to

increased complexity and added friction in their everyday tasks.

I work with various types of companies. These

could be enterprises which are just at the beginning of their digital

transformation or are halfway there, and companies which have adopted a

DevOps culture

culture from the very beginning. I have found there is a stark contrast of

approach between companies that have high and low developer effectiveness.

The easiest way to explain is via a developer day in the life:

Day in the life in a highly effective environment

The developer:

- checks the team project management tool and then attends standup where

she is clear about what she has to work on. - notes that the development environment has been automatically updated

with libraries matching development and production, and the CI/CD

pipelines are green. - pulls down the latest code, makes an incremental code change that is

quickly validated by deploying to a local environment and by running unit

tests. - depends on another team’s business capabilities for her feature. She

is able to find documentation and the API spec through a developer portal.

She still has some queries, so she jumps into the team’s Slack room and

quickly gets some help from another developer who is doing support. - focuses on her task for a few hours without any interruptions.

- takes a break, gets coffee, takes a walk, plays some ping pong with

colleagues. - commits the code change, which then passes through a number of

automated checks before being deployed to production. Releases the change

gradually to users in production, while monitoring business and

operational metrics.

The developer is able to make incremental progress in a day, and goes

home happy.

Day in the life in a low effective environment

The developer:

- starts the day having to deal immediately with a number of alerts for

problems in production. - checks a number of logging and monitoring systems to find the error

report as there are no aggregated logs across systems. - works with operations on the phone and determines that the alerts are

false positives. - has to wait for a response from architecture, security and governance

groups for a previous feature she had completed. - has a day broken up with many meetings, many of which are status

meetings - notes that a previous feature has been approved by reviewers, she

moves it into another branch that kicks off a long nightly E2E test suite

that is almost always red, managed by a siloed QA team. - depends on another team’s API, but she cannot find current

documentation. So instead she talks to a project manager on the other

team, trying to get a query. The ticket to find an answer will take a few

days, so this is blocking her current task.

We could go on. But ultimately the developer doesn’t achieve much,

leaves frustrated and unmotivated

Developer effectiveness

What does being effective mean? As a developer, it is delivering the

maximum value to your customers. It is being able to apply your energy and

innovation in the best ways towards the company’s goals. An effective

environment makes it easy to put useful, high-quality software into

production; and to operate it so that the developers do not have to deal

with unnecessary complexities, frivolous churn or long delays — freeing them

to concentrate on value-adding tasks.

In the example illustrating a low effective environment, everything takes

longer than it should. As a developer, your day is made up of endless

blockers and bureaucracy. It is not just one thing; it is many. This is akin

to death by a 1,000 cuts. Slowly, productivity is destroyed by small

inefficiencies, which have compounding effects. The feeling of inefficiency

spreads throughout the organization beyond just engineering. Engineers end

up feeling helpless; they are unproductive. And worse they accept it, the

way of working becomes an accepted routine defining how development is done.

The developers experience a

learned helplessness.

Whereas in the organization that provides a highly effective environment,

there is a feeling of momentum; everything is easy and efficient, and

developers encounter little friction. They spend more time creating value.

It is this frictionless environment, and the culture that supports it by

fostering the desire and ability to constantly improve, that is the hardest

thing for companies to create when they are doing a digital

transformation.

Being productive motivates developers. Without the friction, they

have time to think creatively and apply themselves

Organizations look for ways to measure developer productivity. The common

anti-pattern is to look at lines of code, feature output or to put too much

focus on trying to spot the underperforming developers. It is better to turn the

conversation around to focus on how the organization is providing an

effective engineering environment. Being productive motivates developers.

Without the friction, they have time to think creatively and apply

themselves. If organizations do not do this, then in my experience the best

engineers will leave. There is no reason for a developer to work in an

ineffective environment when lots of great innovative digital companies are

looking to hire strong technical talent.

Let’s look at an example of a company that has optimized developer effectiveness.

Case Study: Spotify

Spotify conducted user research among their engineers to better

understand developer effectiveness. Through this research, they uncovered

two key findings:

- Fragmentation in the internal tooling. Spotify’s internal

infrastructure and tooling was built as small isolated “islands” leading

to context switching and cognitive load for engineers. - Poor discoverability. Spotify had no central place to find technical

information. As information was spread all over, engineers did not even

know where to start looking for information.

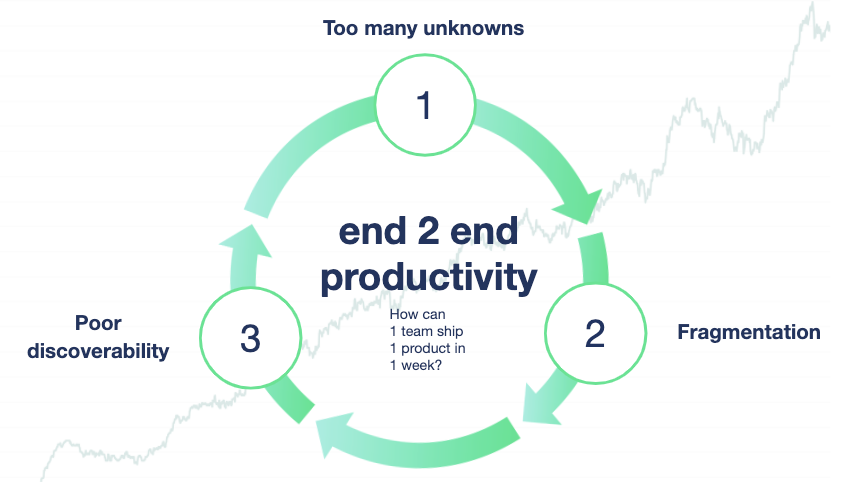

Spotify’s developer experience team describes these problems as a

negative flywheel; a vicious cycle where developers are presented with too

many unknowns, forcing them to make many decisions in isolation, which in

turn compounds fragmentation and duplication of efforts, and ultimately

erodes the end-to-end delivery time of products.

Figure 1: Spotify’s negative flywheel

To mitigate these complexities, they developed Backstage, an Open Source developer portal with a plugin

architecture to help expose all infrastructure products in one place, offering a

coherent developer experience and a starting point for engineers to find the

information they need.

How to get started?

What I am describing in the highly effective environment is what it feels

like to work in a company that has fully embraced a DevOps culture,

continuous delivery and product thinking. Very sensibly, most companies are

on a journey towards achieving this environment. They have read Accelerate

and the State of DevOps report. They

know what type of organization they are striving to build. The four key

metrics (lead time, deployment frequency, MTTR and change fail percentage)

are great measures of DevOps performance.

One way to look at the DevOps measures is that they are lagging indicators. They are useful measurements to

understand where you are, and to indicate when there is work to be done to

figure out what tangible things the company should do to get better.

Ideally, we want to identify leading lower level metrics of effectiveness

that are more actionable. There is a correlation to the higher level

metrics. It will ladder up. This should also be combined with other sources

of research such as surveys on developer satisfaction.

There is an overwhelming amount of good advice, practices, tools, and

processes that you should use to improve. It is very hard to know what to

do. My research has shown that there are a number of key developer

feedback loops. I recommend focusing on optimizing these loops, making them

fast and simple. Measure the length of the feedback loop, the constraints,

and the resulting outcome. When new tools and techniques are introduced,

these metrics can clearly show the degree to which developer effectiveness

is improved or at least isn’t worse.

Feedback Loops

The key loops I have identified are:

Validate a local code change works2 mins5-15 seconds

(depending on tech choice)

Find root cause for defect4-7 days1 day

Validate component integrates with other components3 days – 2 weeks2 hours

Validate a change meets non-functional requirements3 months1 day – 1 week

(depending on scope of change)

Become productive on new team2 months4 weeks

Get answers to an internal technical query1-2 weeks30 mins

Launch a new service in production2-4 months3 days

Validate a change was useful to the customer6 months or never1 – 4 weeks

(depending on scope of change)

The metrics are based on what I have observed is possible. Not every

company needs every feedback loop to be in the high effectiveness bucket,

but they provide concrete goals to guide decision-making. Engineering

organizations should conduct research within their specific context to

figure out what cycles and metrics are important technology strategy.

It is useful to look at what techniques have been applied to optimize the

feedback loops and the journey that companies have taken to get there. Those

case studies can provide many ideas to apply in your own organization.

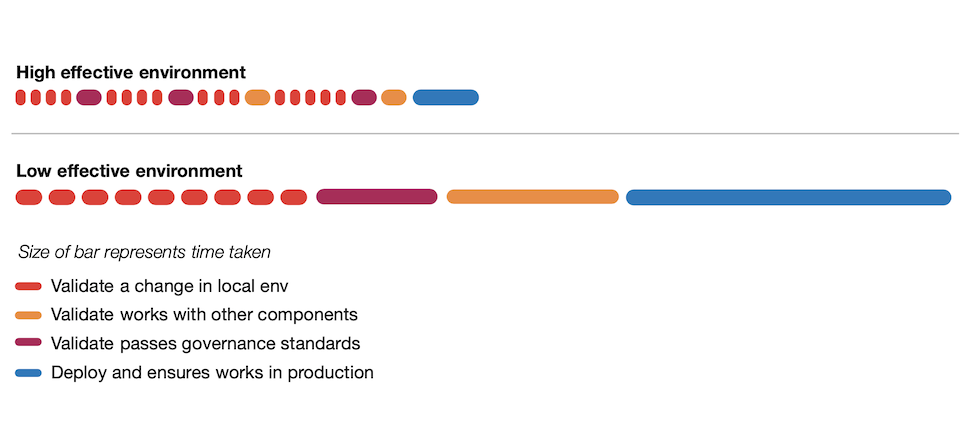

Figure 2: Feedback Loops during feature

development

The diagram above shows a simplified representation of how developers use

feedback loops during development. You can see that the developer validates

their work is meeting the specifications and expected standards at multiple

points along the way. The key observations to note are:

- Developers will run the feedback loops more often if they are

shorter. - Developers will run more often and take action on the result, if

they are seen as valuable to the developer and not purely bureaucratic

overhead. - Getting validation earlier and more often reduces the rework later

on. - Feedback loops that are simple to interpret results, reduce back and

forth communications and cognitive overhead.

When organizations fail to achieve these results, the problems are

quickly compounded. There is a great deal of wasted effort for the

developers. Embodied in the time spent waiting, searching, or trying to

understand results. It adds up, causing significant delays in product

development, which will manifest as lower scores in the four key metrics

(particularly deployment frequency and lead time).

Introducing micro feedback loops

From what I have observed, you have to nail the basics, the things that

developers do 10, 100 or 200 times a day. I call them micro-feedback loops.

This could be running a unit test while fixing a bug. It could be seeing a

code change reflected in your local environment or development environments.

It could be refreshing data in your environment. Developers, if empowered,

will naturally optimize, but often I find the micro-feedback loops have been

neglected. These loops are intentionally short, so you end up dealing with

some very small time increments.

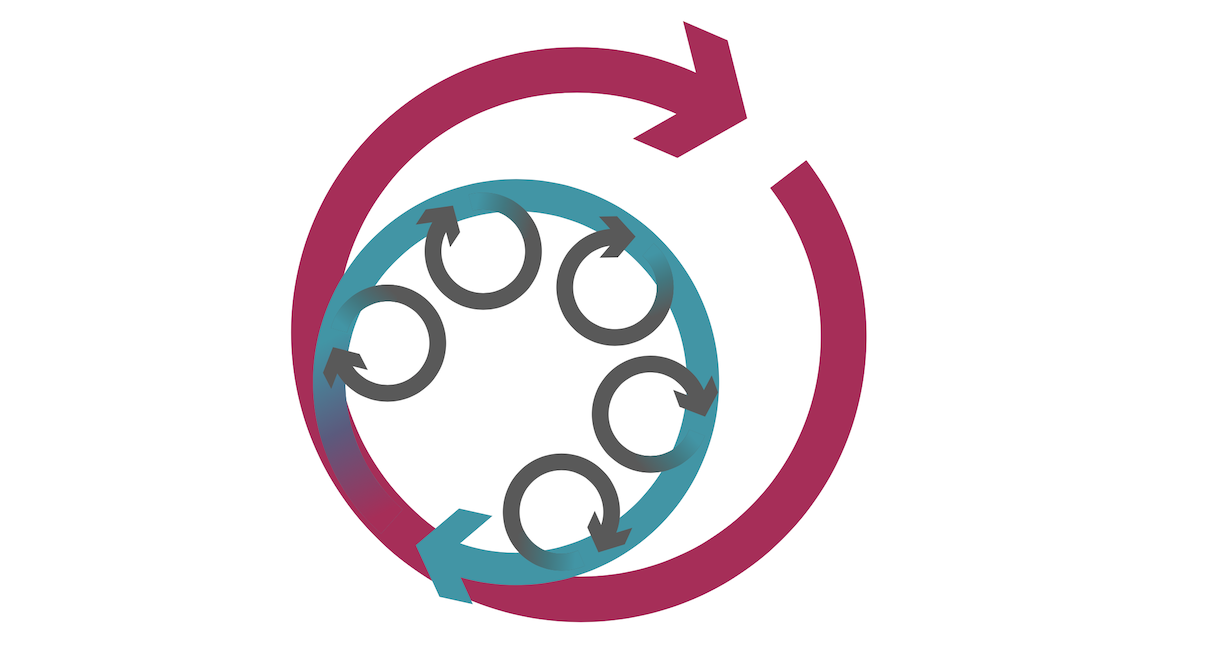

Figure 3: Micro-feedback loops compound to

affect larger feedback loops.

It is hard to explain to management why we have to focus on such small

problems. Why do we have to invest time to optimize a compile stage with a

two minute runtime to instead take only 15 seconds? This might be a lot of

work, perhaps requiring a system to be decoupled into independent

components. It is much easier to understand optimizing something that is

taking two days as something worth taking on.

Those two minutes can add up quickly, and could top 100 minutes a day.

These small pauses are opportunities to lose context and focus. They are

long enough for a developer to get distracted, decide to open an email or go

and get a coffee, so that now they are distracted and out of their state of

flow, there is research that indicates it can

take up to 23 minutes to get back into the state of flow and return to high

productivity. I am not suggesting that engineers should not take breaks and

clear their head occasionally! But they should do that intentionally, not

enforced by the environment.

In reality, developers will compensate by filling these moments of

inactivity with useful things. They might have two tasks going on and toggle

between them. They might slow their compile frequency by batching up

changes. In my research both of these will lead to a delay in integration of

code, and development time.

How far do you take optimizing? When is enough? Imagine that now we have

that change down to 15 seconds, but we think we can get it to three

seconds. Is that worth the investment? It depends on how difficult it is to

make that change and the impact it will bring. If you can develop a tool or

capability that will speed up 10 teams then it might be worth it. This is

where platform thinking, rather than optimizing for individual teams, comes

into play.

Distributed systems are a particular challenge. There are many valid

reasons for splitting systems into different deployable units (usually

microservices). However, distributed systems also make many things difficult

(see Microservice

Prerequisites), including developer effectiveness. Sometimes teams

might optimize for team autonomy or for runtime performance, but they sacrifice

developer effectiveness because they do not invest in maintaining fast

feedback loops. This is a very common situation my company runs into.

We’re releasing this article in installments. The next installment will

look at the steps to improve these feedback loops and the lessons Etsy learned from

focusing on developer effectiveness

To find out when we publish the next installment subscribe to the

site’s

RSS feed, or

Martin’s twitter stream