In many organizations today there is one thing that almost always is true: there

are too many things done in parallel, there is too much work-in-progress,

everyone is busy but nothing gets done. If this is so ubiquitous why is no one

doing anything about it? Are people not aware or do they not know how to fix it?

This is so predominant, that it almost is too easy to just claim:

recommending less work in progress/process is almost cheating…bc so many companies are operating above optimal WIP, you’ll almost always be right.

then again, there’s theoretically optimal … and optimally meeting the desire to look (and feel) extremely busy

— John Cutler (@johncutlefish) September 14, 2020

One aspect I keep getting back to is the notion of software engineering

organizations as production lines. As engineer I certainly refused this notion

because software engineering is creative work, not repetitive moves in an

assembly line. But the analogies made in The Phoenix Project and The

Unicorn Project are way too convincing. Having gone through what in

hindsight almost feels like a text book example of a manager applying

exactly The Phoenix Project I come to believe that this is in fact the

perfect analogy. Today, I fundamentally believe that the difference between a

manager and a good manager is their level of understanding of it.

One simple blog post is surely not enough to dive into this topic. Many books

have been written on the subject by people much more experienced than I am. This

post is about an introduction to the topic, my own experience on it, and an

invitation to read more about the topic.

Why is too much WIP bad?

The first and most important question of course is to understand that having too

much WIP is in fact bad. With too many projects in flight, the communication

between individuals increases. Decision making is getting more complex with each

additional stake-holder involved. And eventually everyone ends up working on the

topic where the fire is burning most.

I want to illustrate the issue and it’s effects using systems thinking and

a little turn-based game. This is modeled using Will Larson’s Systems

library and is heavily inspired by his post on Why limiting work-in-progress

works.

The rules are simple: each round we put in effort in the form of development.

Ideas are turned into projects. We start, and finish them. Each transition, from

project, to started, to finished is done at a certain rate. The game is played

for ten rounds. In three scenarios I will demonstrate the effects of limiting

WIP.

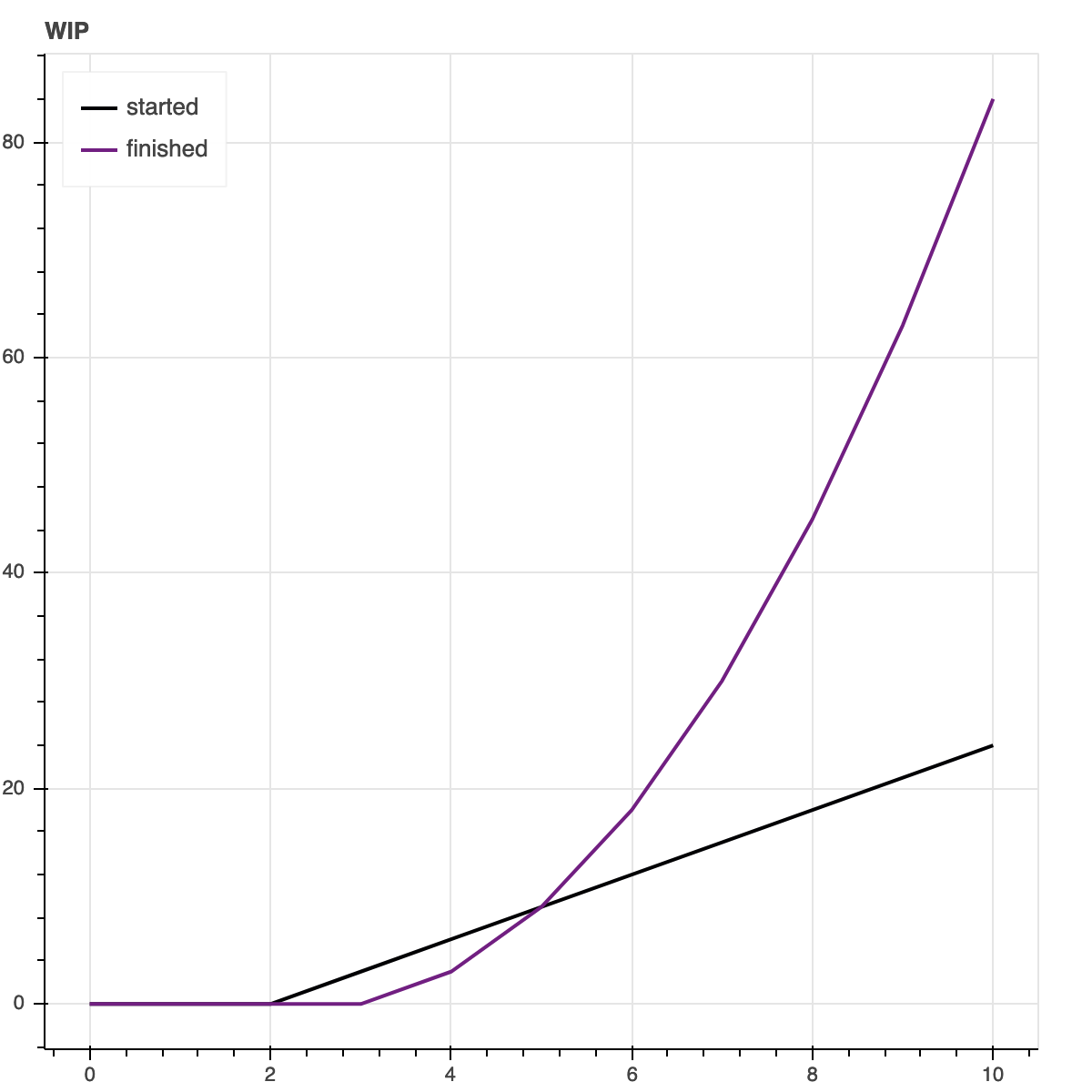

An ideal world

In the first scenario we play the game in an ideal world. Each project can be

started and stopped within one round respectively. The rate by which we start

and finish projects are determined by the development effort we put in.

[] > Development @ 3

[Ideas] > Projects @ Development

Projects > Started @ Development

Started > Finished @ Development

The result can be seen here. In just ten rounds we are able to finish 84

projects. Quite remarkable.

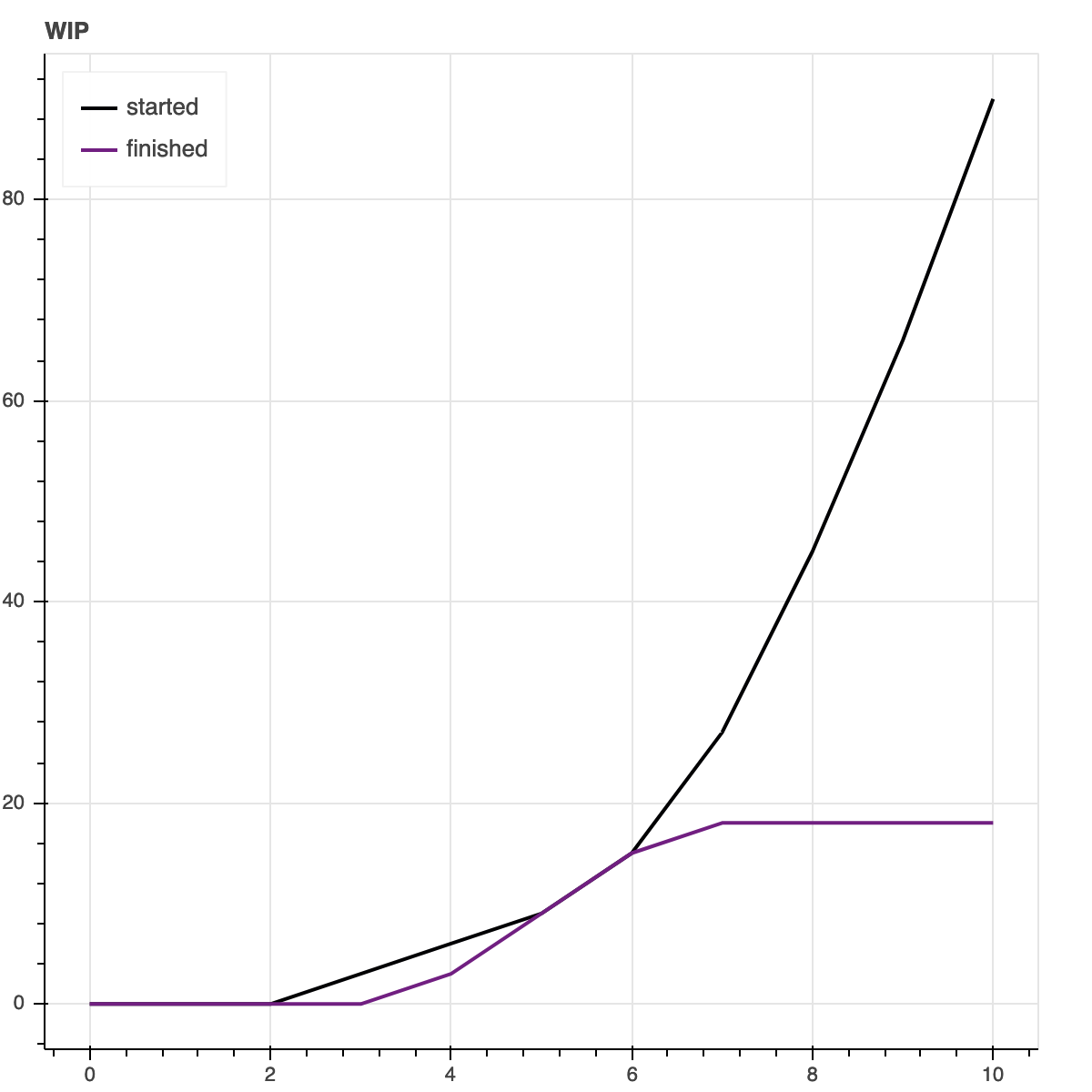

Projects that take longer

In reality we usually don’t finish all projects in each round. Instead we have

projects move over to the next round. We model this by reducing the finish

rate to the difference between the development capacity and the started

projects.

What this essentially means is that we can only finish projects, when there is

more capacity in development compared to started projects. The result is,

that we reach a ceiling of finished projects, while the number of started

projects keeps increasing. We are all busy but nothing gets done!

[] > Development @ 3

[Ideas] > Projects @ Development

Projects > Started @ Development

Started > Finished @ Development - Started

The system is so overwhelmed that it stops finishing projects. From round seven

on the system is only able to start new projects without ever finishing anything

ever after. The started projects are ever growing.

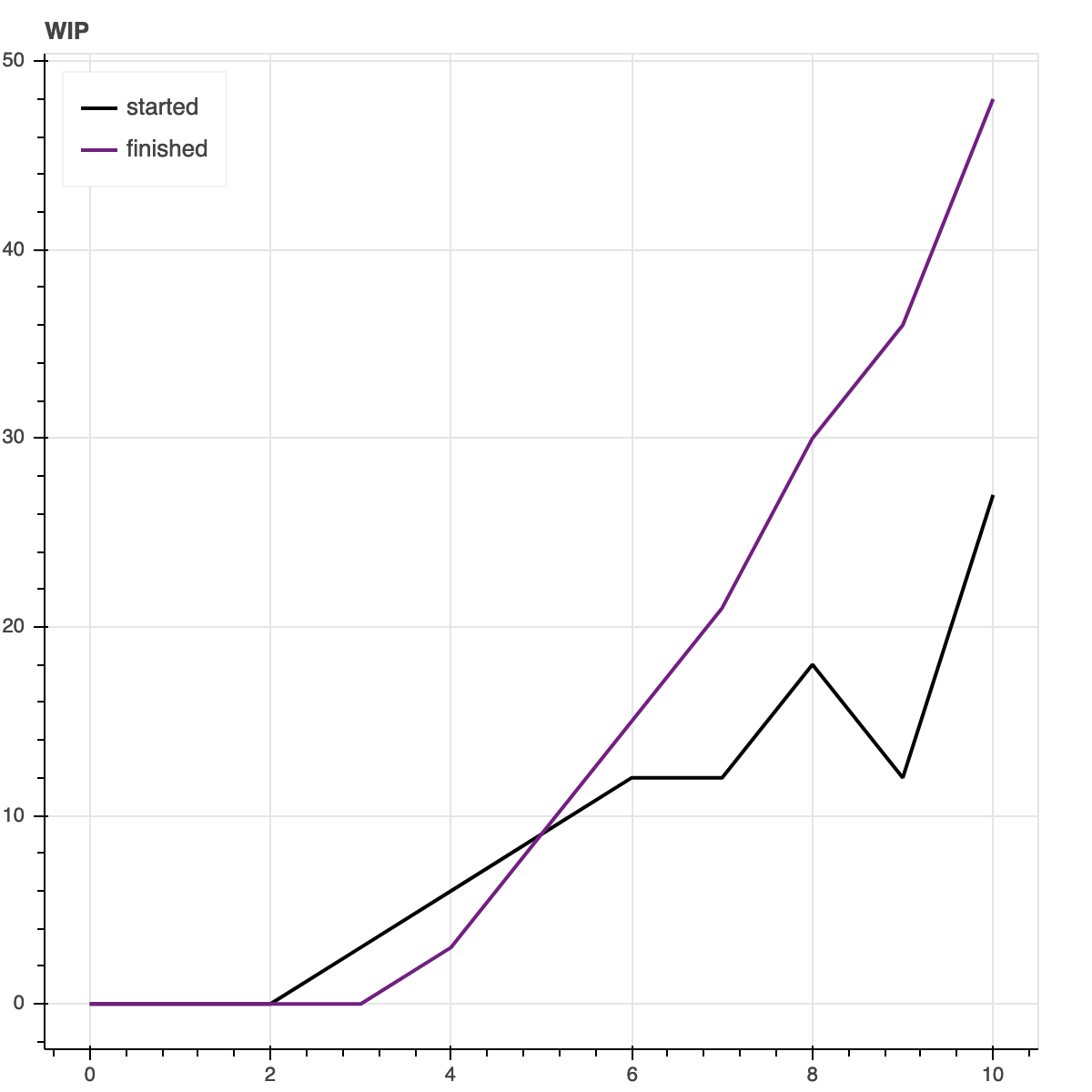

Limiting WIP

The fix for this is of course to limit the number of projects we start! To do

this, we adjust the rate of started projects similarly to the finish rate.

This improves the amount of finished projects to 27 after ten rounds.

[] > Development @ 3

[Ideas] > Projects @ Development

Projects > Started @ Development - Started

Started > Finished @ Development - Started

We can create an even better outcome by reducing the rate of started projects

even more:

[] > Development @ 3

[Ideas] > Projects @ Development

Projects > Started @ Development - (2 * Started)

Started > Finished @ Development - Started

This time we are finishing 48 projects!

Reducing the number of projects started even more does not have any effect at

this point. The only way to improve the system’s output is by adding more

development effort.

Key Insights

I want to highlight two key insights here. The first one is that we can improve

the output of a team or an organization by limiting work in progress.

Fundamentally this means that we need to find the sweet spot between starting

and finishing projects. A system that rewards starting projects will inherently

fall into the trap of having too much WIP and eventually not be able to finish

anything meaningful.

The role of management and leadership is to introduce barriers into when and how

to start a new project. Additionally, celebrating finished projects that meet

the quality bar is also important. Finishing a project and handing over the

technical debt to another team means it is not finished.

The second insight is that having small batches is favorable compared to large

projects that are taken over into the next rounds. If the projects are of a size

that can be finished within an iteration, the system is able to get a lot more

done.

The larger an organization is, the more likely large projects become. More

people and teams need to align on a solution and more sign-offs are required

from different departments. Limiting the number of those large projects in

flight will have two effects: there will inherently be a higher quality bar on

the projects started and there will be more room for small batches to occur

within teams.

Symptoms of too much WIP

In the context of a team the first indicator of too much WIP usually is that

everyone in the team is working on something different. For every engineer in

the team there is a separate task or even project. Daily stand ups are centered

around people not work. There are also very few interactions between people

during the stand up, so everyone just pushes their current status to the group.

The next obvious symptom is that everyone is busy but nothing gets done. In

Scrum or Kanban you can easily visualize this by introducing a Waiting for

Review state for example. Watch how it will grow over time as people are

starting new tasks before reviewing other’s work.

Usually starting the next task is more important that finishing what is

basically already finished but just needs a quick looks good to me (LGTM).

Another side effect of having too much WIP is a decline in the quality of work

produced. If everyone just quickly adds a LGTM to a PR, we miss things and

certainly do not have the code in the best possible way. Only one person has

worked on it in an opinionated way.

Fixing WIP in real life

The practical fixes are of course not as simple as described in the models

above. How can I find out what the ideal WIP limit is for the system I am in? So

far I have started working with teams suffering from too much WIP. In those

circumstances I found it best to start radical and limit the WIP to one. This

can be one project or one main priority or the one thing we really need to

get done in the next round.

Usually it takes a team a few iterations to learn. Before they were all busy

and all working on many things. Now they might sometimes feel there is nothing

to do and wonder what they should do with their free time. It only takes a few

iterations though until collaboration within the team increases. This means

earlier feedback loops on work-in-progress. The quality of finished projects

increases which leads to a smaller number of incidents, fewer bugs, and less

re-work.

After a few iterations and having recorded the learnings in retrospectives, we

collectively decided to increase the WIP. This was an important step for me and

the team: we were slowly learning to work on more than one topic in parallel

while not sacrificing quality. From there on: rinse and repeat.

Conclusion

Limiting work-in-progress is the tool every manager and leader needs to have

in their tool belt. This is the one super power that over time will allow moving

faster to the desired goal.

Unfortunately, most managers today are not aware of this and just keep pushing

their teams to work faster. And fast usually means working on many topics at

the same time.

It just feels good to always be busy.