Why Everyone Always Hates Redesigns, Even When They’re Good

The strange psychology that shapes your reactions

In Microprocessing, columnist Angela Lashbrook aims to improve your relationship with technology every week. Microprocessing goes deep on the little things that define your online life today to give you a better tomorrow.

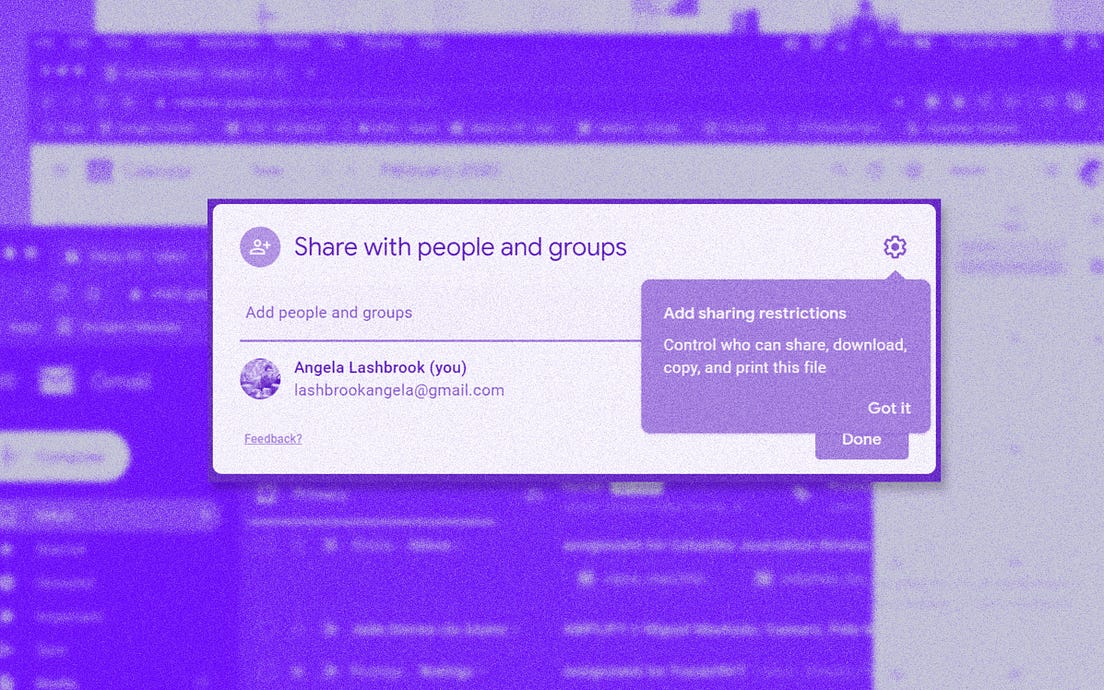

Whenever a popular web interface gets any kind of significant visual change, a lot of people react with confusion, dismay, and even anger. This month, it’s the new Google Docs sharing interface: The Next Web wrote an entire piece detailing complaints about the new sharing menu. One podcaster says she “just doesn’t like it,” and others are “completely baffled.”

Though the obvious reason people react so negatively to product redesigns and updates appears straightforward enough — people dislike change — the mechanisms behind why people get so frustrated, and what designers and companies have to do to mitigate that anger, is more complicated.

One theory, the “endowment effect,” helps explain this aversion to the new. It posits that people prefer what they already have, regardless of the benefits they may gain from adopting something new, because they are afraid of what they might lose. A 1990 study, one of the first to provide evidence for the idea, helps illustrate how it works. The study separated participants into three groups. The first group was given a choice between two objects: a mug or a chocolate bar. The group was more or less evenly split between their choices. A second group was given mugs, but they were allowed to later exchange it for a chocolate bar if they so desired. A third group was given a chocolate bar and likewise allowed to later switch it out for a mug.

The two latter groups largely refrained from switching out their original items for something new, despite the first group being evenly split on what they went with. The researchers gathered from this experiment that even though people may equally prefer two items if presented with them simultaneously, they’ll almost always prefer the item they already have when offered something new later.

Thus the “endowment effect” — people favor what they’re already “endowed” with over what they could have instead. Another, relevant theory is known as the “status quo effect,” which says people prefer what they’re already familiar with versus something new, even when there’s a strong possibility that the new thing could dramatically improve their lives. It is, quite simply, easier to stick with what you know than adapt to what you don’t; adopting a new technology means you need to disrupt your workflow and take the time and energy to learn something new. The lazy approach (which, to be clear, most people take) is to stay with the old, crappy version.

So, even if the change to Google Docs was objectively better than what everyone had before, people were still going to be pissed off, because they’re naturally inclined to prefer what they already had. Looking at it from another angle, though, consumers aren’t the only ones with an issue: Designers tend to overestimate the value of their products, or at least how much consumers will value them. John Gourville, a professor at Harvard Business School, calls this the “9x effect”: Consumers value what they have as three times better than what they stand to gain, while designers overvalue their new creation by the same factor. “The result is a mismatch of nine to one, or 9x, between what innovators think consumers desire and what consumers really want,” Gourville wrote in a 2006 piece for the Harvard Business Review.

This disconnect between designers and consumers is a frequent contributor to innovations that don’t quite hit the mark with users, says Lars Perner, an assistant professor of clinical marketing at University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business.

“With technology-driven companies run by engineers, they may go more with values of technical excellence,” without taking into account what users truly want or need, Perner says. At these companies, designers are “surrounded by people who are more technically savvy and who will maybe be more receptive to some of those designs.”

So, if the company does limited public testing and instead relies on its employees to gauge how positively users are going to react to a new release, it’s going to get a skewed perspective. Communities built around specific industries tend to place higher demands on their product than the general customer base; compare, for example, the sort of wine a sommelier may prefer compared to your average, run-of-the mill drinker who just wants a $10 bottle of pinot noir.

This isn’t to say you can’t eventually work those $10 pinot drinkers up to, say, an unfiltered sparkling wine. It just needs to be done with a customer-first strategy that fully takes into account that people need to be eased into new features and product changes. Designers should emphasize how painless it is to level up, focusing only on the advantages of the new product in later messaging. A 2016 study investigated how study participants might be persuaded to rent electric cars instead of the diesel cars they were accustomed to. It found that users were overwhelmed by the new technology and afraid that it would inconvenience them or that they would have to change their behavior to use it. Consumers almost always prefer inaction, as it is cognitively easier, the researchers state. So, if designers want to effectively market new technology to users, they need to do so in a way that emphasizes how easy the changes are to implement instead of focusing on how amazing they are.

Of course, as with the Google Docs update, customers often aren’t given much of a choice. Allowing people to opt in to changes can potentially make them more amenable to them, even if they decide to hold off. “Sometimes just the option of ‘Do you want to use the beta now?’ or ‘Do you want to wait until this officially rolls out?’” can improve how well a new release will land with consumers, says Mark Hall, a user experience strategist and instructor at the University of California San Diego Extension. The Google Docs rollout, on the other hand, did not offer this. “Control is a big thing, especially when we have fewer things under control now,” he says.

I tend to sign up for the beta option, as I find it fun to experiment with new features before they’re released to the general public. I’m even more likely to endure any glitches and bugs if I signed on voluntarily. But when sites roll out significant product changes without warning or explanation, without any apparent input from their wider customer base, and with little prospect of going back to the old interface, it’s easy to see why people will get frustrated, especially in a time when we’re already feeling powerless and unmoored. Does a change to the Google Docs sharing interface or how Twitter displays reply threads really matter? Beyond a few moments of initial irritation and a learning curve, no, not really. We’ll acclimate eventually. Companies know that and count on our irritation fading with time, though there are exceptions. (I’m still angry at Apple’s introduction of the dongle, which I felt forced into adopting and years later don’t believe has been anything other than a nuisance.) But customers aren’t robots, and design hits us on an emotional level, even if it isn’t anything close to a life-or-death issue. And right now, everyone’s a little raw.

“Designs that advance the organization’s ego instead of solving the customer’s problem are the most frustrating and the least likely to succeed,” says Jeffrey Zeldman, a creative director at Automattic, the company behind WordPress and Tumblr, and an instructor of interaction design at the School of Visual Arts. “Folks will forgive shoddy graphic design, slow performance, and other sins if the design, for all its other failings, lets the customer feel empowered.” Smart design, he says, works with customers, rather than dictating down to them.

So, sure, maybe your brain, like nearly everyone else’s, is lazy and fearful, and that’s why you’re struggling with the new Google Docs, or Twitter threads, or whatever. But if customers are a group of rowdy, disagreeable children, designers are the adults in the room who are tasked with communicating and delegating changes sensitively. When they release new changes to people’s workflows at a time when their jobs and lives are already massively disrupted, is it any wonder people are going to be upset?