We’re not going back to normal

Social distancing is here to stay for much more than a few weeks. It will upend our way of life, in some ways forever.

To stop coronavirus we will need to radically change almost everything we do: how we work, exercise, socialize, shop, manage our health, educate our kids, take care of family members.

We all want things to go back to normal quickly. But what most of us have probably not yet realized—yet will soon—is that things won’t go back to normal after a few weeks, or even a few months. Some things never will.

You can read all our coverage of the coronavirus/Covid-19 outbreak for free, and also sign up for our coronavirus newsletter. But please consider subscribing to support our nonprofit journalism.

It’s now widely agreed (even by Britain, finally) that every country needs to “flatten the curve”: impose social distancing to slow the spread of the virus so that the number of people sick at once doesn’t cause the health-care system to collapse, as it is threatening to do in Italy right now. That means the pandemic needs to last, at a low level, until either enough people have had Covid-19 to leave most immune (assuming immunity lasts for years, which we don’t know) or there’s a vaccine.

How long would that take, and how draconian do social restrictions need to be? Yesterday President Donald Trump, announcing new guidelines such as a 10-person limit on gatherings, said that “with several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly.” In China, six weeks of lockdown are beginning to ease now that new cases have fallen to a trickle.

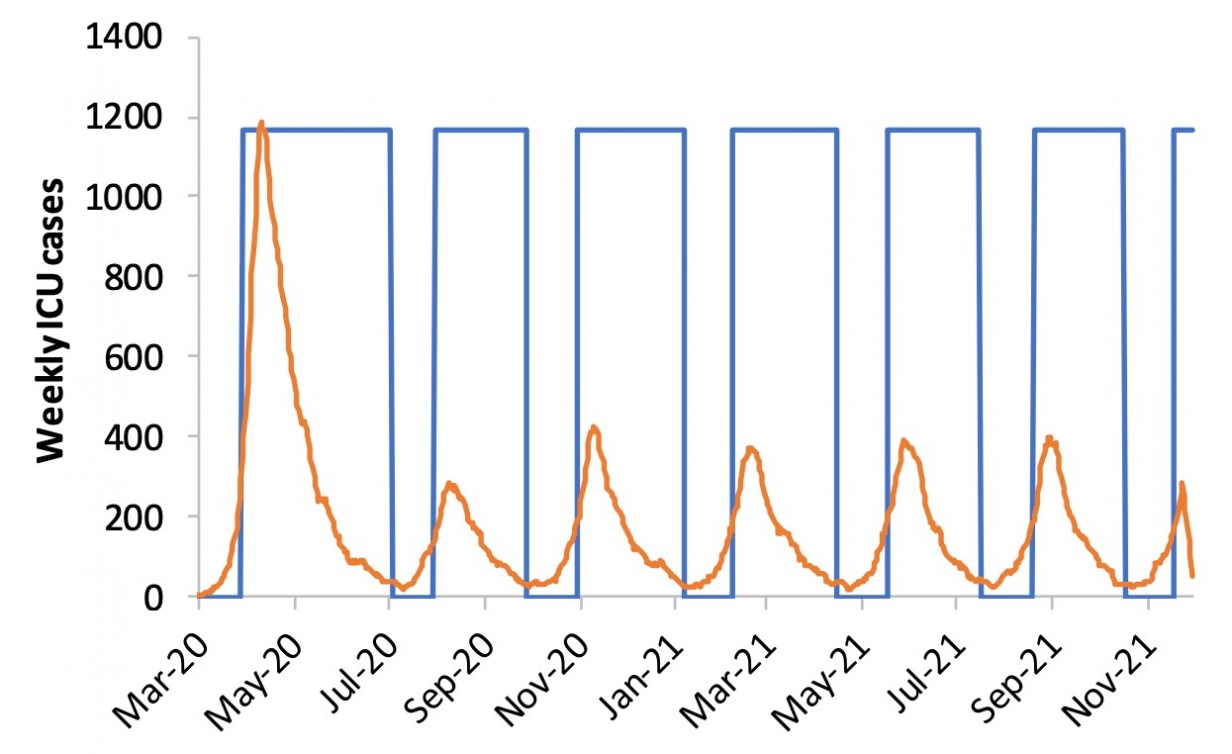

But it won’t end there. As long as someone in the world has the virus, breakouts can and will keep recurring without stringent controls to contain them. In a report yesterday (pdf), researchers at Imperial College London proposed a way of doing this: impose more extreme social distancing measures every time admissions to intensive care units (ICUs) start to spike, and relax them each time admissions fall. Here’s how that looks in a graph.

The orange line is ICU admissions. Each time they rise above a threshold—say, 100 per week—the country would close all schools and most universities and adopt social distancing. When they drop below 50, those measures would be lifted, but people with symptoms or whose family members have symptoms would still be confined at home.

What counts as “social distancing”? The researchers define it as “All households reduce contact outside household, school or workplace by 75%.” That doesn’t mean you get to go out with your friends once a week instead of four times. It means everyone does everything they can to minimize social contact, and overall, the number of contacts falls by 75%.

Under this model, the researchers conclude, social distancing and school closures would need to be in force some two-thirds of the time—roughly two months on and one month off—until a vaccine is available, which will take at least 18 months (if it works at all). They note that the results are “qualitatively similar for the US.”

Eighteen months!? Surely there must be other solutions. Why not just build more ICUs and treat more people at once, for example?

Well, in the researchers’ model, that didn’t solve the problem. Without social distancing of the whole population, they found, even the best mitigation strategy—which means isolation or quarantine of the sick, the old, and those who have been exposed, plus school closures—would still lead to a surge of critically ill people eight times bigger than the US or UK system can cope with. (That’s the lowest, blue curve in the graph below; the flat red line is the current number of ICU beds.) Even if you set factories to churn out beds and ventilators and all the other facilities and supplies, you’d still need far more nurses and doctors to take care of everyone.

How about imposing restrictions for just one batch of five months or so? No good—once measures are lifted, the pandemic breaks out all over again, only this time it’s in winter, the worst time for overstretched health-care systems.

And what if we decided to be brutal: set the threshold number of ICU admissions for triggering social distancing much higher, accepting that many more patients would die? Turns out it makes little difference. Even in the least restrictive of the Imperial College scenarios, we’re shut in more than half the time.

This isn’t a temporary disruption. It’s the start of a completely different way of life.

Living in a state of pandemic

In the short term, this will be hugely damaging to businesses that rely on people coming together in large numbers: restaurants, cafes, bars, nightclubs, gyms, hotels, theaters, cinemas, art galleries, shopping malls, craft fairs, museums, musicians and other performers, sporting venues (and sports teams), conference venues (and conference producers), cruise lines, airlines, public transportation, private schools, day-care centers. That’s to say nothing of the stresses on parents thrust into home-schooling their kids, people trying to care for elderly relatives without exposing them to the virus, people trapped in abusive relationships, and anyone without a financial cushion to deal with swings in income.

There’ll be some adaptation, of course: gyms could start selling home equipment and online training sessions, for example. We’ll see an explosion of new services in what’s already been dubbed the “shut-in economy.” One can also wax hopeful about the way some habits might change—less carbon-burning travel, more local supply chains, more walking and biking.

But the disruption to many, many businesses and livelihoods will be impossible to manage. And the shut-in lifestyle just isn’t sustainable for such long periods.

So how can we live in this new world? Part of the answer—hopefully—will be better health-care systems, with pandemic response units that can move quickly to identify and contain outbreaks before they start to spread, and the ability to quickly ramp up production of medical equipment, testing kits, and drugs. Those will be too late to stop Covid-19, but they’ll help with future pandemics.

In the near term, we’ll probably find awkward compromises that allow us to retain some semblance of a social life. Maybe movie theaters will take out half their seats, meetings will be held in larger rooms with spaced-out chairs, and gyms will require you to book workouts ahead of time so they don’t get crowded.

Ultimately, however, I predict that we’ll restore the ability to socialize safely by developing more sophisticated ways to identify who is a disease risk and who isn’t, and discriminating—legally—against those who are.

We can see harbingers of this in the measures some countries are taking today. Israel is going to use the cell-phone location data with which its intelligence services track terrorists to trace people who’ve been in touch with known carriers of the virus. Singapore does exhaustive contact tracing and publishes detailed data on each known case, all but identifying people by name.

We don’t know exactly what this new future looks like, of course. But one can imagine a world in which, to get on a flight, perhaps you’ll have to be signed up to a service that tracks your movements via your phone. The airline wouldn’t be able to see where you’d gone, but it would get an alert if you’d been close to known infected people or disease hot spots. There’d be similar requirements at the entrance to large venues, government buildings, or public transport hubs. There would be temperature scanners everywhere, and your workplace might demand you wear a monitor that tracks your temperature or other vital signs. Where nightclubs ask for proof of age, in future they might ask for proof of immunity—an identity card or some kind of digital verification via your phone, showing you’ve already recovered from or been vaccinated against the latest virus strains.

We’ll adapt to and accept such measures, much as we’ve adapted to increasingly stringent airport security screenings in the wake of terrorist attacks. The intrusive surveillance will be considered a small price to pay for the basic freedom to be with other people.

As usual, however, the true cost will be borne by the poorest and weakest. People with less access to health care, or who live in more disease-prone areas, will now also be more frequently shut out of places and opportunities open to everyone else. Gig workers—from drivers to plumbers to freelance yoga instructors—will see their jobs become even more precarious. Immigrants, refugees, the undocumented, and ex-convicts will face yet another obstacle to gaining a foothold in society.

Moreover, unless there are strict rules on how someone’s risk for disease is assessed, governments or companies could choose any criteria—you’re high-risk if you earn less than $50,000 a year, are in a family of more than six people, and live in certain parts of the country, for example. That creates scope for algorithmic bias and hidden discrimination, as happened last year with an algorithm used by US health insurers that turned out to inadvertently favor white people.

The world has changed many times, and it is changing again. All of us will have to adapt to a new way of living, working, and forging relationships. But as with all change, there will be some who lose more than most, and they will be the ones who have lost far too much already. The best we can hope for is that the depth of this crisis will finally force countries—the US, in particular—to fix the yawning social inequities that make large swaths of their populations so intensely vulnerable.

Coronavirus

Mar 17

A new app would say if you’ve crossed paths with someone who is infected

Private Kit: Safe Paths shares information about your movements in a privacy-preserving way—and could let health officials tackle coronavirus hot spots.

Amazon

6hAmazon is hiring 100,000 new workers in the US to deal with the coronavirus boom

The hiring spree is to cope with an unprecedented surge in demand for online deliveries during the outbreak.

Coronavirus

Mar 16

How bad can coronavirus get in the US? We’re about to find out.

The key question right now is how similar the US will be to Italy.

Coronavirus

Mar 16A new report issued by a group of experts advising the UK government offers a blistering assessment of the country’s previous “herd immunity” approach to coronavirus, suggesting that as many as…

The background: Last week, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that his country would adopt a different coronavirus strategy from the ones its European neighbors have followed. Most governments have sought to suppress the spread of the virus by reducing mass gatherings, imposing quarantine restrictions, and encouraging social distancing. But Johnson said the country would forgo such measures with an unusual plan to prevent the outbreak from overwhelming the health-care system and protect the most vulnerable groups during peak infection seasons. Under the strategy, at least 60% of the population were expected to contract the virus and get better—mostly younger individuals who would face only a mild form of illness. The government believed this would result in a “herd immunity” that would subsequently protect vulnerable groups from infection, while avoiding “behavioral fatigue” that would cause people to stop cooperating with safety measures over time.

Sharp realizations: That strategy was met with fierce criticism over the weekend. The Covid-19 Response Team based at Imperial College in London revealed on Monday that the government’s experts realized only over the last few days that its policy would “likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths”—potentially 250,000—and that the burden on health systems would exceed their capacities and resources by as much as eight times.

“We were expecting herd immunity to build,” Azra Ghani, head of infectious disease epidemiology at Imperial College, told reporters Monday. “We now realize it’s not possible to cope with that.” Instead, the report advocates suppressing the virus with aggressive measures that would keep case numbers consistently low, in line with what many other countries are doing.

Correcting the ship: The UK government seems to have realized its errors and is now scrambling to to do better. On Monday, Johnson asked people to avoid “non-essential contact” and refrain from going to crowded spaces and venues. A ban on mass gatherings starts Tuesday. Families were urged to stay home for 14 days should any members exhibit symptoms, not going out “even to buy food or essentials.”

“The aim now is not to slow the rate of growth of cases, but pull the epidemic in reverse,” Neil Ferguson, an epidemiologist at Imperial College, told reporters Monday. “Hopefully there will [only] be tens of thousands of deaths. Maybe just a few thousand.”

Unfortunately, the report also suggests that isolation and social distancing might have to remain in effect until a viable coronavirus vaccine is produced, which could take as long as 18 months. “The only exit strategy is really vaccination or other forms of innovative technology,” Ferguson.

This story is part of our ongoing coverage of the coronavirus/Covid-19 outbreak. You can also sign up to our dedicated newsletter.

Sponsored

Smartphone innovation in the third decade of the 21st century

Mobile devices have come a long way, building on their traditional phone function to become general-purpose communication consoles. In 2020, they’ll get better, faster, stronger yet.

Coronavirus

Mar 16Over 24,000 coronavirus research papers are now available in one place

The data set aims to accelerate scientific research that could fight the Covid-19 pandemic.

Computing

Mar 16A new computer chip mimics the neurocircuitry of our noses to smell

It draws inspiration from the structure and electrical activity of the brain to distinguish between odors.

Chinese hackers and others are exploiting coronavirus fears for cyber espionage

Smartphone innovation in the third decade of the 21st century

Our new podcast

Deep Tech

Go deeper on our best stories and ideas with this subscriber-only podcast (free for a limited time).

Artificial intelligence

March 13

Lie detectors have always been suspect. AI has made the problem worse.

An in-depth investigation into artificial-intelligence-based attempts to recognize deception.

Coronavirus

Mar 13US coronavirus testing is slowly ramping up, but way too late

Private and academic labs are rushing to fill the void left by CDC’s mistakes, hoping to slow the deadly pandemic in the US.

Coronavirus

Mar 13Worst-case coronavirus scenario: 214 million Americans infected, 1.7 million dead

The worst-case figures are what would happen if no action is taken to slow the virus, which spreads person to person.

Coronavirus

Mar 12No, coronavirus is not a good argument for quitting cash

Though it’s theoretically possible, there is no evidence that physical money—or any inanimate surface, for that matter—helps the virus spread.

Coronavirus

Mar 13