How to Build a PaaS for 1500 Engineers

This article is based on a presentation I gave as part of

AdevintaTalks in Barcelona on November 2019.

I’m experimenting with this format: I went through the slides typing what

I’d speak over them, edited the text, and added some of the most

relevant slides inbetween paragraphs.

Let me know how it works.

–

Today’s topic is about Technical Infrastructure, a term I found first in

a great talk by Will Larson.

He defines Technical Infrastructure as “the software and systems to

create, evolve, and operate our businesses.” That includes Cloud

services, build tools, compilers, editors, source control systems, data

infrastructure (Kafka, Hadoop, Airflow…), routing and messaging

systems (Envoy, gRPC, Thrift…), Chef, Consul, Puppet, Terraform, and

so on.

Companies that reach a certain size typically create one or more teams

that take care of different subsets of those tools. They get named

something like “infrastructure”, “platform”, “foundations”… I will

use “Platform team” in this text.

If you have been part of one, you will know that life for a Platform

team is tough. I could find an actual picture that shows one of them on

the field:

Pieter Brueghel the Elder – “The Triumph of Death” (1562)

A good deal of the job is ultimately about finding the right balances

between standardization and autonomy. To make meaningful impact,

Platform teams depend on having standards in their organization. Trying

to too support every possible language ecosystem, framework, DB,

messaging system, and whatnot spreads Platforms teams too thin to be

effective.

On the other hand, it is also wise to respect every other team’s

autonomy to make their own technical decisions. Oppinionated Platform

teams risk coming across as a patronizing, ivory-tower-dwelling jerks

that impose capricious choices on other engineering teams.

Standardization and autonomy are complex factors to juggle.

What if you multiplied this problem by 20? What if you had 20 companies

to support, each with their own cocktail of technologies, cultures,

philias and phobias, genealogies of decisions… and their own Platform

team!

That’s my team’s job at Adevinta. Adevinta builds online marketplaces.

Each of them are and need to be special in their own way. At the same

time, they all share many other bits and pieces that don’t need to be

different. That are, in fact, more cost-effective if they are built once

and shared by all. Much of this falls in the category of Technical

Infrastructure. My team works on that type of plumbing.

Generating value as a Platform team

You know who these people are?

They are the way fiction represents a profit centre. Those are parts of

a company that bring money in, they generate revenue.

You know who these other people are?

They don’t smell of money, right? Fiction represents them in this way

because they belong to a cost centre. They pay AWS bills, buy

computers. In other words, money exits the company through them.

Profit centres tend to have a crisp value proposition that is easy to

see and understand. It’s the opposite for cost centres. This doesn’t

mean that they give no value to the company. On the contrary: that

Kubernetes cluster is critical for the business. What is hard is

explaining to the people in the first picture why the engineering team

should spend cycles migrating from EC2 to Kubernetes instead of just

shipping more money-generating features.

In a way, cost centres are valuable to the extent that they power-up the

profit centres. This is why Platform teams should be aware that they

live under constant scrutiny, visible or not. The business will always

wonder, why are we paying this team of expensive engineers? Can’t

Amazon, or Google, or Microsoft, or Digital Ocean, or Heroku, or whoever

else, provide whatever these people do? Can’t we make use of those

many open source projects funded by

dozens of commercial companies, and use the headcount elsewhere?

In 2020, Technical Infrastructure is a hot market. While I gave this

talk, Amazon was running Re:Invent in

Las Vegas. The first day they announced Quantum computing as a

service.

They continued for an entire week running presentations that felt like..

So when a Platform team comes with their quarterly demo the perception

is hopelessly.. small.

And those internal demos are great, don’t get me wrong, a lot of effort

and that. But when a Platform team is (intentionally or not) building

systems that have 3rd party alternatives they are competing in an uneven

playing field. A Platform team should really avoid competing against

AWS, Google, or any commercial company. It doesn’t matter if their

homegrown CI system is superior, today, to $commercial_ci_system. The

market will catch up, faster than expected, and make that team

redundant. Every Platform team should be asking themselves: what is our

differentiator? What do we offer than makes it worthwhile for our

company to invest in our team, rather than throwing those engineers

at the product?

To recap so far: because Platform teams are cost centers, they must

really focus on formulating a clear and realistic value proposition that

is relevant to the business. They must also ensure that their impact is

intelligible to the business, and visible. Finally, they must ensure

that those properties remain within a fast-moving industry.

Our PaaS

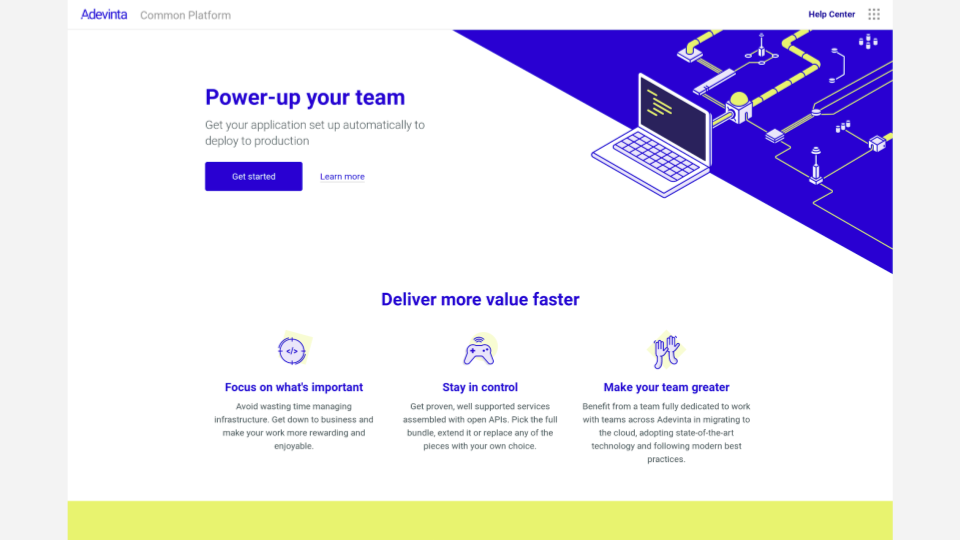

My team focuses on a PaaS that helps engineers across Adevinta build,

deploy and operate software in the cloud. We focus mainly on stateless

workloads (e.g. microservices.)

Our pitch for product engineers is simple: “look, we know you’re

fighting in a competitive market. Our mission is to help you win that

competition. You prefer to do the plumbing yourself? It’s your call, we

respect that. But if you prefer to focus your attention on your product

we have a team of domain experts that do the heavy lifing for you. We

take care of providing you with the technical infrastructure that you

need so you can focus on winning races”.

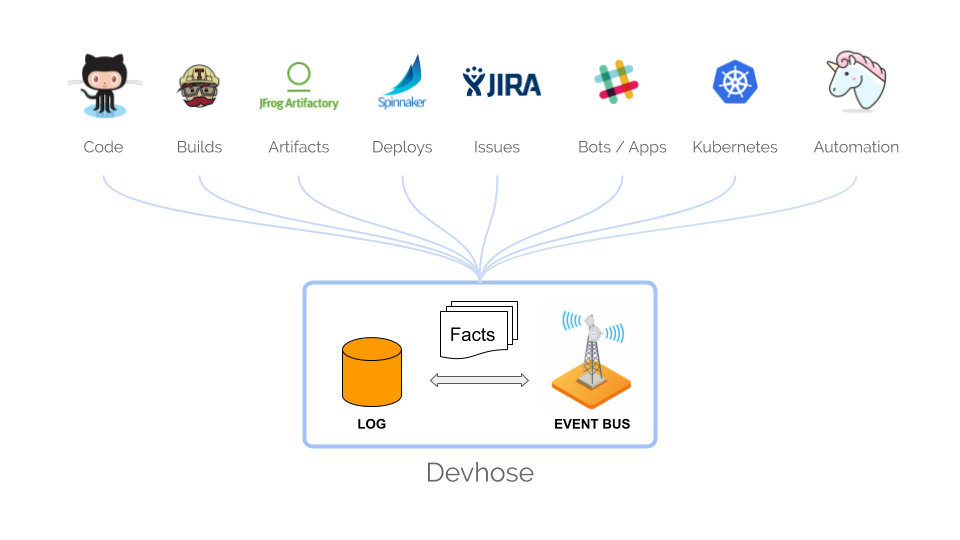

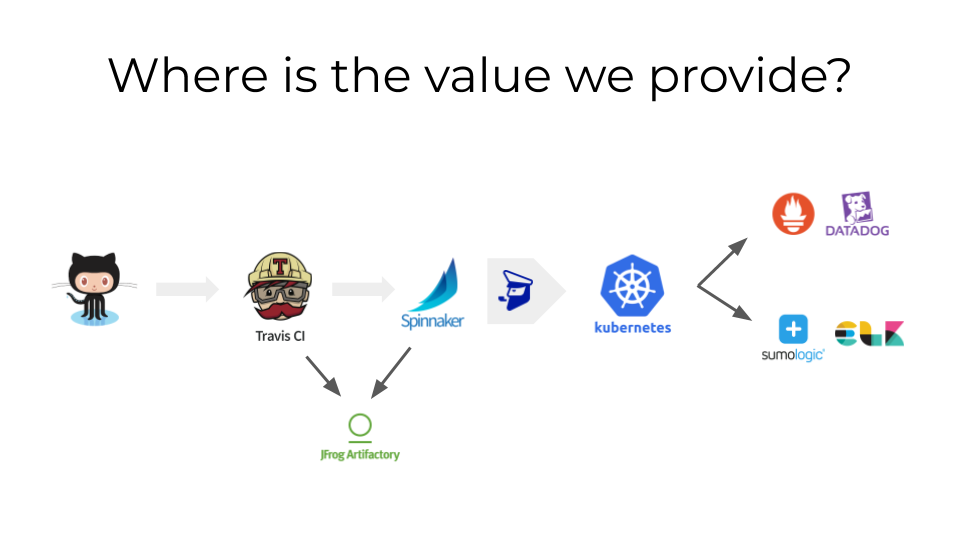

We define a Golden

Path:

a reduced set of sane, proven choices of tools that are effective to

build, deploy, and operate microservices (the core systems we support

are in the left-hand side slide below). Is each tool the best in their

category? Probably not. But we know they get the job done, are well

supported, maintained, and standardised in the industry. It’s not about

local optimums, but global maximums.

It also not about chosing a bunch of random pieces and give product

teams an Ikea-like platform that they must assemble piece by piece.

We bundle GitHub, Travis, Artifactory, Spinnaker, FIAAS, Kubernetes,

Prometheus, Datadog, Sumologic, ELK.

The main value we provide is in the joints, the articulation, the

glue. In how we integrate together all these systems. Our PaaS

favours composition of multiple modular components, trying to become a

pierceable abstraction.

The main benefits are:

- Avoid losing battles with commercial companies. Each of our

components has at least one whole company behind it. It’s hardly

realistic to expect that we can dedicate 5-7 of our engineers (1/4th

of the team!) to build in-house alternatives to a CI system, a CD

system, a metrics platform, etc. against businesses that have 20 or 50

times that capacity. Instead, we focus on what is specific for our

company, tailoring off-the-shelf solutions to our needs. Commercial

competitors are more likely to focus on what’s generic to larger

portions of the industry. - Well defined articulations become escape hatches for those teams that

can’t or won’t use the entire bundle. This is a requirement to be

able to support a highly heterogeneous population of companies and

teams as we do. But it’s also good for us as it increases adoption,

and creates low-friction “gateway drugs” to the full PaaS. We often

see how teams that adopt one tool gradually adopt more organically as

they gain trust and realize we can relieve them from doing a lot of

undifferentiated heavy lifting. - The same flexibility enables us to replace individual pieces when it

makes sense, causing minimal impact for the users. One of our current

initiatives is to ensure that upgrading or switching any of those

pieces is completely transparent to users.

Small impact, repeated many times

One of the strategies we use is to spot where we can introduce tools

that generate small impact to a wide surface. This worked quite well

applied to reducing toil on the development process.

Of most of the tasks involved in getting a new change merged to the main

tree, there may be only two that really need involving human brains:

writing the code, and reviewing it. We set out to automate lots of the

other small chores in the dev process: assigning reviewers, analyzing

coverage and static analysis reports, propagating dependency updates,

keeping branches up to date with their base, merging approved PRs…

Each of these actions may have a tiny impact. But multiplied by a

population of hundreds of engineers, month after month, you get

economies of scale.

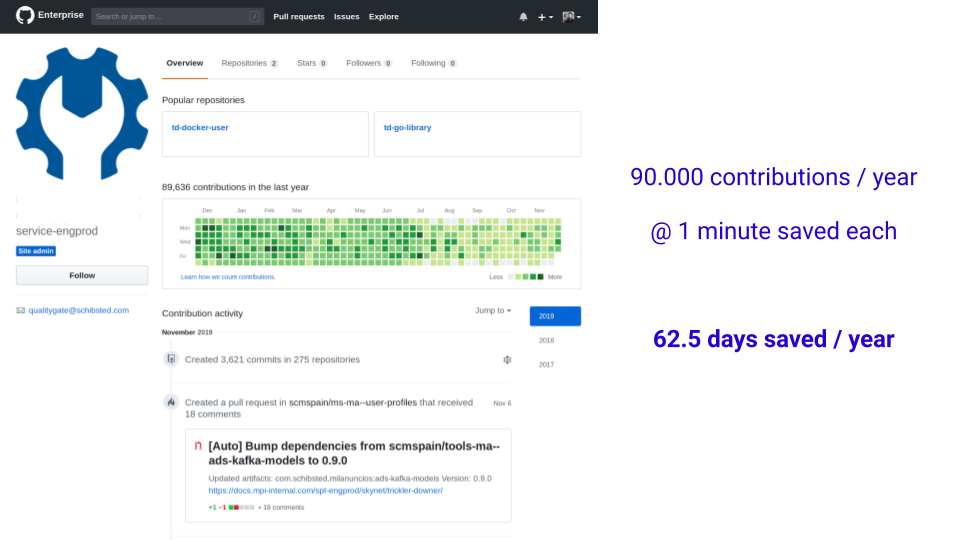

The image above is the profile for the service user that executes all

these actions in our internal GitHub Enterprise instance. Assuming each

action is worth 1 minute (many of them are actually more than that) it

adds up to 62 engineer-days per year. That’s impact that can be very

easily translated to money, to terms that the rest of the business can

understand.

At this point you should have a siren wailing in your heads. “Wait,

you said before that we should avoid competing with commercial

companies. GitHub released

Actions earlier this year, and

some of the automation you just mentioned seems very similar to what is

available in the public GitHub. Does that mean your team has just

become obsolete?”

Remember the point about creating differentiators. The core

functionality that makes the PaaS (things like “running builds” or

“store these metrics and let me query them”, or “do $something when a

PR is created”) will become commoditized sooner or later. But glue is a

different story. Our differentiator here is simple: GitHub Actions can

only react to GitHub events. Our automation can react to events in the

entire Adevinta development ecosystem. All of it.

Because we didn’t spend that much time building the core tools, we could

focus on the glue. The slide above shows Devhose, a component that

collects events from every tool in our dev ecosystem (GitHub, Travis,

Spinnaker, Artifactory, JIRA, Slack, Kubernetes… and even several

tools outside of the Golden Path), stores them in a log, and broadcasts

them in an “engineering event bus”. We also built some tooling around

it that gives us the ability to easily implement new functionalities

that interact back with the ecosystem. For example, one bot we

prototyped recently listens to events in Kubernetes, detects killed

pods, collects troubleshooting information and ships it to a Slack

channel so the team that owns the service is alerted.

Thanks to having invested in glue, when GitHub Actions reaches the

Enterprise version, it will bring value that we can leverage, rather

than an existential threat.

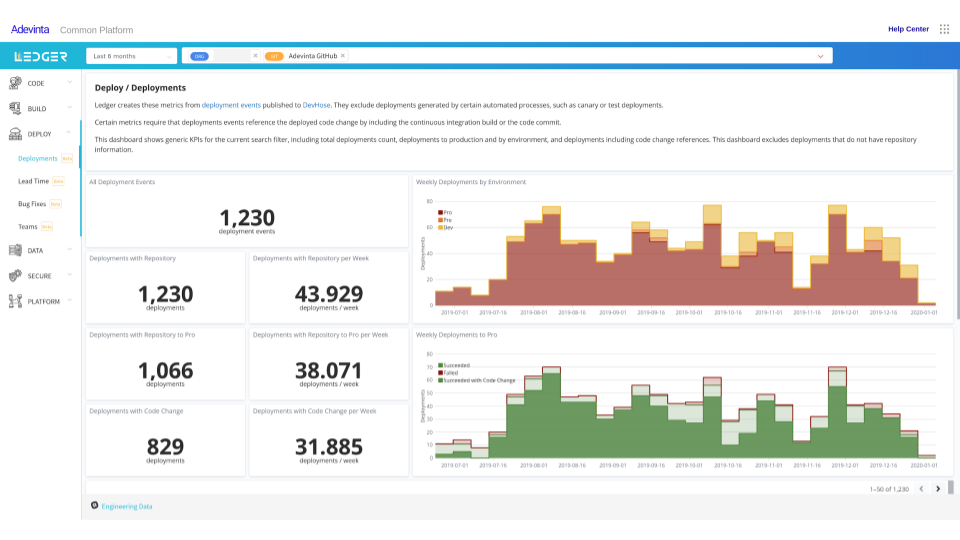

Virtuous feedback loops

Having everything that happens in our dev ecosystem registered and

broadcast in an event bus turned out to be valuable for multiple

purposes. One of them was to build insights into the development

process itself.

We built a system called Ledger to help with this. It is an event

consumer that reads from Devhose’s event bus and crunches all types of

productivity metrics. Which ones? One of our references is

Accelerate

and their annual “State of Devops” reports

(2018,

2019).

Their main claim is that the performance of software delivery teams can

and does provide a competitive advantage to companies. This is backed

by extensive industry research that links specific practises to the most

effective and efficient ways to develop and deliver technology. This is

precisely our team’s mission.

The authors identify four key

metrics that capture the

effectiveness of the dev & delivery process: Lead Time for Changes,

Change Failure Rate, Deployment Frequency, and Time to Restore. These

can be used as high level performance indicators that reliably gauge the

ability of an organisation to achieve its goals.

Because we provide the plumbing for most engineering processes, we are

in the right place to measure them. Here is one of our dashboards about

Continuous Delivery, including Deployment Frequency, one of the

Accelerate indicators.

Teams that use our PaaS get these out of the box. Along with a lot more

metrics. Build durations, code coverage, static analysis issues,

security issues, lead time for changes, stats about the code review

process, etc.

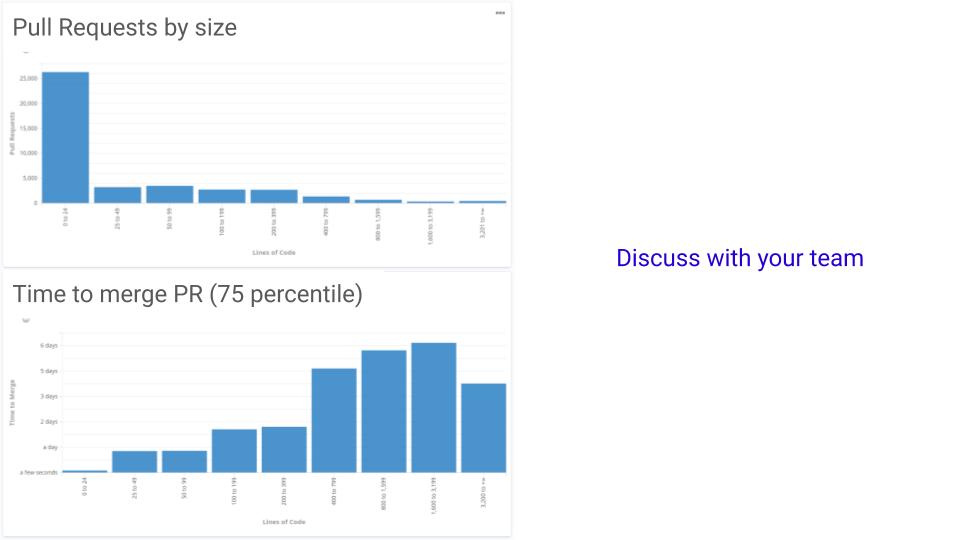

I have a certain liking to the Code tab, that shows the correlation

between Pull Request size and time to merge in their team. Here is an

example:

You have surely noticed at least two interesting details:

- It’s obvious that small PRs get merged faster. In fact, differences

of just a couple dozen lines double the time to merge from hours to

days. - Even though time to merge grows with PR size, it looks like very large

PRs (the last bucket) take a lot less to merge. You can guess why.

This example is a good way to show how Ledger helps us influence best

practises without confrontation, enforcement, or alienating engineers.

We bring no opinions to the table. We show over 2 years worth of data

that is contextualized for a whole team, a whole company, but never

exposes personally identifiable information. We care about how teams

perform, not how many points of code coverage are accountable to

$engineer. This is not a tool for managers to measure performance, but

for teams to understand and make informed decisions about their

processes.

Again, does this have some overlap with tools like

SonarQube? Definitely. But we have

differentiators. We can analyze everything in the dev process, not just

code quality. We can tailor to the deploy and release workflows most

common to our teams. We can enrich data with organisational information

specific to Adevinta’s org chart. We can correlate quality with other

phases in the process (e.g. the space we want to move into next is

answering questions like “Does high code coverage correlate to less

incidents?”). We can reprocess over 2 years of raw data on demand and

generate new stats as we develop them (or fix bugs :).

The Accelerate report notes that these indicators can be used in two

ways. Teams can inform improvements in their software delivery

performance. Organisations can learn how to support engineering

productivity with metrics that are intelligible to non-technical

stakeholders. In other words, by providing these metrics, we

facilitate a conversation between tech and business, between cost and

profit centres. And precisely because we measure the productivity of

teams, we can also measure in what degree our job delivers on our

mission: support teams to deliver at their best.

Investing in a component

Sometimes we do invest in components of the Platform.

In the talk I didn’t have time to go over

Spinnaker, where we’ve been (and remain) active

contributors for ~4 years along with Netflix, Google, Target and many

others. Being part of the community made it easier for us to upstream

features that made sense for us, such as Cloud Formation

support or

integrations with Travis,

as well as dozens of bug fixes and other improvements.

But the best example of in-house investments are the Kubernetes clusters

we build and operate on EC2. The inevitable question is: why not use

EKS, GKE, or other managed solutions?

The “glue” strategy should already come to mind.

Below is a simplified comparison of what a raw installation of

Kubernetes provides, and what our clusters provide. A bare Kubernetes

cluster works, you can schedule containers, but that’s pretty much it.

GKE, EKS, etc. provide slightly more than the left picture: they may

autoscale nodes and handle other basic ops burden. But they are still

far from covering the typical needs of product teams that wish to run

production workloads securely, with little to no operational burden.

Some examples:

Our clusters are multi-tenant, allowing several marketplaces to share

infrastructure securely while optimizing costs through higher density.

We deal with all the cons of multitenancy. We handle network isolation

for each tenant. We provide sensible defaults, pod security policies,

etc. We added a validating webhook to the NGINX ingress controller

that we contributed

upstream, to

reduce the blast radius of ingresses that break the NGINX

configuration.

We maintain clusters in several geographical regions. This is

instrumental for some of Adevinta’s central teams that build centralised

functions like Messaging, Reputation systems, etc. that are meant to be

used in several marketplaces that serve users in distant geographical

locations (from Europe to Latin America). Our clusters offer a

homogeneous, managed runtime environments, close to all Marketplaces,

where central functions can be deployed.

In every cluster we provide integrations that work out of the box. You

get automatic certificates leveraging

cert-manager and Let’s

Encrypt. Users can use authentication tokens

generated through our company’s SSO. They get metrics automatically

scraped and sent to Datadog or our internal Prometheus, as they chose

with a simple config option. The same feature is provided for logs.

Users can avoid learning the full Kubernetes and use

FIAAS, a commodity abstraction on top of

Kubernetes. It was created in-house at one of our

marketplaces ~7 years ago and was OSS’d in early 2019.

In every cluster we run automated canary tests periodically that deploy

canonical applications and test connectivity and most integrations, we

try to detect problems earlier than our users. Our team provides

dedicated, 24/7/365 on-call.

We do full-stack aware upgrades. Because Google or AWS may upgrade your

Kubernetes version, but will not care about the integrity of everything

you’ve got running

there.

We upgrade at a slower pace than GKE/EKS, but when we do we ensure that the

entire stack bundled in our cluster works, not just the core of

Kubernetes.

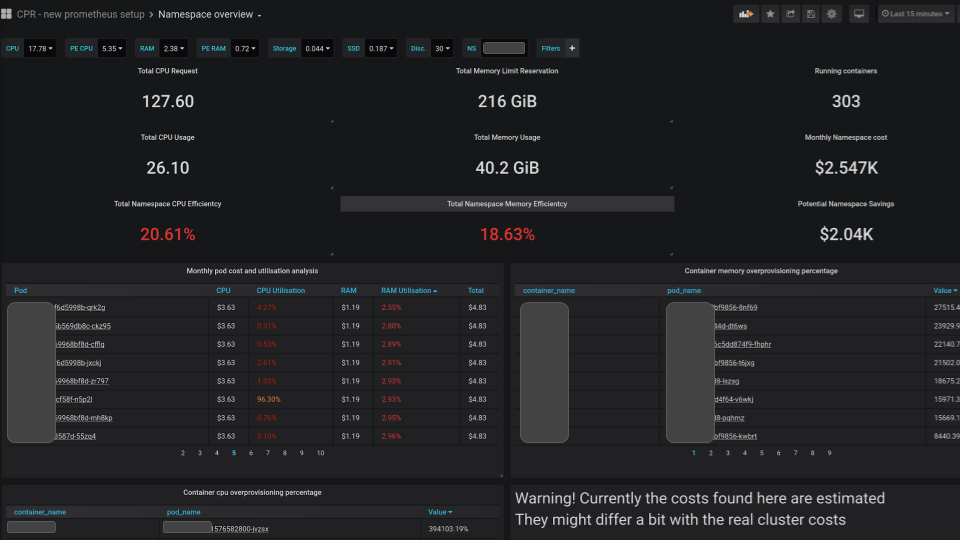

And we provide insights into your costs down to the pod level, informing

users about potential savings if they are over-provisioning. Here is a

PoC of a Grafana dashboard with this info:

I made a point before about creating articulations that facilitate

pivoting to commercial choices once they become commoditized. That’s

our strategy with EKS. We keep a close eye on its roadmap and have

given feedback about our needs to AWS. As soon as EKS is a suitable

base Kubernetes installation for us, we are ready to lift-and-shift our

integrations on top.

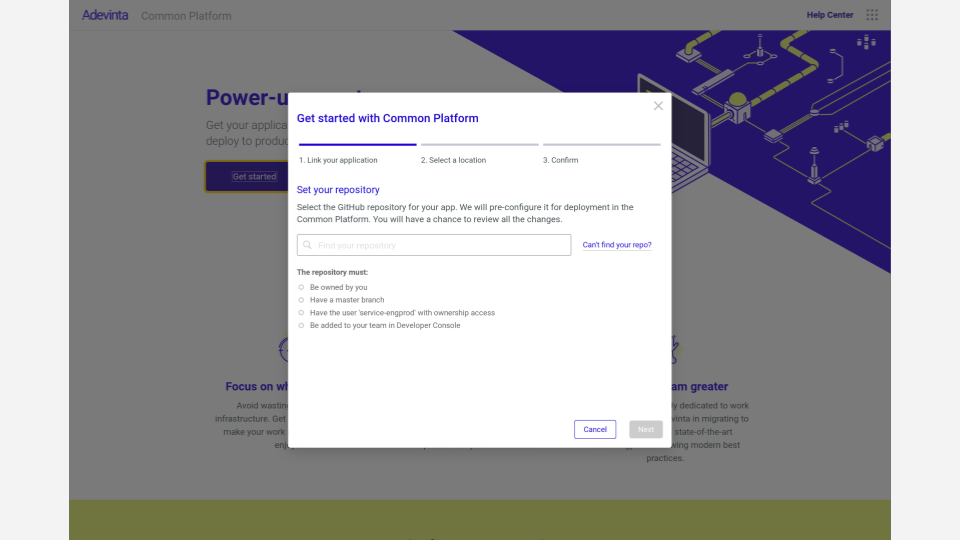

Zero-friction onboarding

All this is (possibly) quite cool, but if engineers need weeks or months

to start using it, nobody will. That was one of our top challenges a

year ago. The core components in the PaaS were mostly there, but each

team would have to spend days or weeks configuring each of them by hand

on their repositories. Throughout the last year we’ve invested heavily

in streamlining the onboarding process. We turned what was an Ikea-like

experience into an almost seamless process. Users get a web interface,

enter their repository URL, click on a button, and our automation takes

it from there. It takes ~10 minutes for their repository to be

automatically configured with CI/CD pipelines, deploying to their team’s

private namespace, and integrated with metrics and logging systems. If

something fails or manual action is required from our Platform teams,

the onboarding tool notifies, keeps track of the issue in JIRA, and

resumes the process when we’ve unblocked it.

There is a point about the importance of automation here, but I want to

stress something else. If you buy the proposition that Platform teams

have a significant degree of competing scope with commercial companies,

UX spacialists are a must-have. A team big enough to serve

hundreds of engineers must reserve headcount for a good UX designer. It

will pay off. Not only will you stop inflicting backend-made-UIs to

your engineers, but also because the Platform team will learn how to

understand the needs of their users, test their assumptions (most of

which will be wrong), the impact they make with their work, and deliver

a more professional product.

The team in charge of those automation and UIs has been using

instrumentation data collected in the onboarding process to polish the

experience, improve the failure rate and cover corner cases. Last

quarter they moved on to solving other pain points in the

platform. For example, troubleshooting a failed deploy. Right after

Christmas we plan to release a team dashboard with all applications

maintained by a given team. It summarizes status for each, and

highlights when something fails in the build, deployment pipelines, or

runtime, with relevant information collected from any system in the

PaaS. Again, glue.

Change hurts, we should feel it too

Regardless of the effort we put in to improving the onboarding experience

for our users, at the end of the day we’re moving engineers from a known

territory, their on-prem infra, EC2, or wherever they run their

services today, to an unknown one. At some point, every migration

feels like this.

Théodore Géricault – The Raft of the Medusa. (1819)

When this happens, someone from our team should sail in that raft with

them.

Specially for mid/large sized migration projects, we allocate at least

1-2 of our engineers to support teams on-site. To give an example, we

now have an ongoing migration project for ~200 microservices from all

the Spanish sites. For several

months we’ve had engineers from our team, as well as the local Platform

team inside Adevinta Spain sitting together in a shared seating area.

Both share OKRs, regular plannings, weekly syncs, etc. In our previous

engagement with the Subito.it team, three of

our engineers travelled to Italy for several weeks during the quarter.

We are also creating different workshops that we reuse and adapt for

newly onboarded teams, including Kubernetes basics, hands-on exercises,

etc.

There are two key outcomes to working closely to our users:

- Trust: engineers in the product teams stop perceiving those in the

Platform teams as a Slack handle, but actual people with faces that

they can confidently ask questions to. The local Platform teams in

the marketplaces start seeing us as partners rather than an

existential threat. - Engineers in our Platform team learn the needs of product engineers,

and gain experience on how it feels to use the tools we build. They

also leverage the expertise of local Platform teams that have been

working in this space for years in their respective marketplaces.

While it’s hard to leave your team for weeks or months, the experience

is an eye-opener and everyone brings invaluable insights back to our

teams.

Is it working?

It’s a bumpy ride by nature, but yes. How do we measure it?

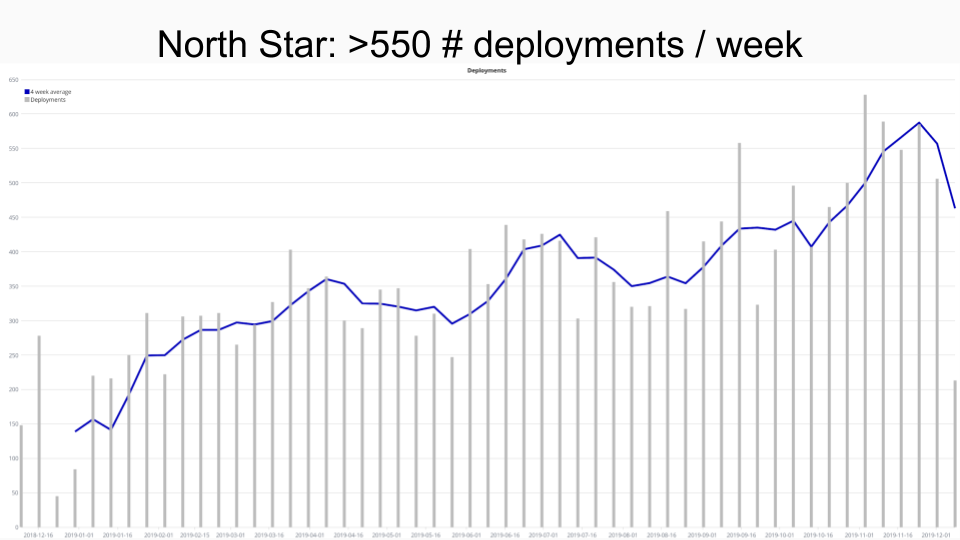

As I mentioned above, metrics like those proposed by Accelerate seemed

relevant as they measure precisely the properties we wish to improve.

After getting some help from a Itamar

Gilad, a professional product

management consultant, we settled for Successful Deployments per

week as our North

Star.

We believe it is a good proxy for productive habits that we want to

incentivise: deployments are easy and automated, work reaches users

early, and defects can be repaired quickly. For us, more frequent

deployments have two positive implications: more services use our PaaS,

and those that use it behave productively by deploying more often. We

only count “Successful” deployments to ensure that our tools help and

incentivise pushing healthy code out.

Here is our North Star tracking dashboard for the past year (the dip at

the right is just the last incomplete period.)

This quarter we’ve spent time collecting a whole set of other metrics

that influence the North Star (e.g. number of active repos, build

durations, etc.) and are fundamental to defining good OKRs.

Harder to quantify, but easier to appreciate, is feedback from our

users. A couple of days before the talk we found this in Twitter from

an engineer in one of the Spanish marketplaces that were onboarding the

Platform in those days.

Translation: “The transition to Kubernetes is going so well that I’m

not feeling it. Basically everything works perfectly. Hat tip to everyone who

made it.”

We have lots of rough edges and potential for improvement, but it feels

we are in the right track. My +10 for that hat tip to all the excellent

colleagues that have contributed to making this possible, from

infrastructure to UX and everything inbetween.