Software Architecture Patterns

Chapter 3. Microkernel Architecture

The microkernel architecture pattern (sometimes referred to as the plug-in architecture pattern) is a natural pattern for implementing product-based applications. A product-based application is one that is packaged and made available for download in versions as a typical third-party product. However, many companies also develop and release their internal business applications like software products, complete with versions, release notes, and pluggable features. These are also a natural fit for this pattern. The microkernel architecture pattern allows you to add additional application features as plug-ins to the core application, providing extensibility as well as feature separation and isolation.

Pattern Description

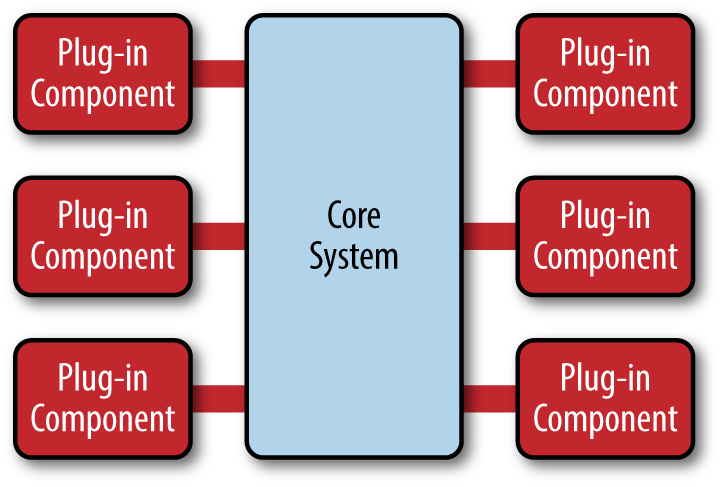

The microkernel architecture pattern consists of two types of architecture components: a core system and plug-in modules. Application logic is divided between independent plug-in modules and the basic core system, providing extensibility, flexibility, and isolation of application features and custom processing logic. Figure 3-1 illustrates the basic microkernel architecture pattern.

The core system of the microkernel architecture pattern traditionally contains only the minimal functionality required to make the system operational. Many operating systems implement the microkernel architecture pattern, hence the origin of this pattern’s name. From a business-application perspective, the core system is often defined as the general business logic sans custom code for special cases, special rules, or complex conditional processing.

Figure 3-1. Microkernel architecture pattern

The plug-in modules are stand-alone, independent components that contain specialized processing, additional features, and custom code that is meant to enhance or extend the core system to produce additional business capabilities. Generally, plug-in modules should be independent of other plug-in modules, but you can certainly design plug-ins that require other plug-ins to be present. Either way, it is important to keep the communication between plug-ins to a minimum to avoid dependency issues.

The core system needs to know about which plug-in modules are available and how to get to them. One common way of implementing this is through some sort of plug-in registry. This registry contains information about each plug-in module, including things like its name, data contract, and remote access protocol details (depending on how the plug-in is connected to the core system). For example, a plug-in for tax software that flags high-risk tax audit items might have a registry entry that contains the name of the service (AuditChecker), the data contract (input data and output data), and the contract format (XML). It might also contain a WSDL (Web Services Definition Language) if the plug-in is accessed through SOAP.

Plug-in modules can be connected to the core system through a variety of ways, including OSGi (open service gateway initiative), messaging, web services, or even direct point-to-point binding (i.e., object instantiation). The type of connection you use depends on the type of application you are building (small product or large business application) and your specific needs (e.g., single deploy or distributed deployment). The architecture pattern itself does not specify any of these implementation details, only that the plug-in modules must remain independent from one another.

The contracts between the plug-in modules and the core system can range anywhere from standard contracts to custom ones. Custom contracts are typically found in situations where plug-in components are developed by a third party where you have no control over the contract used by the plug-in. In such cases, it is common to create an adapter between the plug-in contact and your standard contract so that the core system doesn’t need specialized code for each plug-in. When creating standard contracts (usually implemented through XML or a Java Map), it is important to remember to create a versioning strategy right from the start.

Pattern Examples

Perhaps the best example of the microkernel architecture is the Eclipse IDE. Downloading the basic Eclipse product provides you little more than a fancy editor. However, once you start adding plug-ins, it becomes a highly customizable and useful product. Internet browsers are another common product example using the microkernel architecture: viewers and other plug-ins add additional capabilities that are not otherwise found in the basic browser (i.e., core system).

The examples are endless for product-based software, but what about large business applications? The microkernel architecture applies to these situations as well. To illustrate this point, let’s use another insurance company example, but this time one involving insurance claims processing.

Claims processing is a very complicated process. Each state has different rules and regulations for what is and isn’t allowed in an insurance claim. For example, some states allow free windshield replacement if your windshield is damaged by a rock, whereas other states do not. This creates an almost infinite set of conditions for a standard claims process.

Not surprisingly, most insurance claims applications leverage large and complex rules engines to handle much of this complexity. However, these rules engines can grow into a complex big ball of mud where changing one rule impacts other rules, or making a simple rule change requires an army of analysts, developers, and testers. Using the microkernel architecture pattern can solve many of these issues.

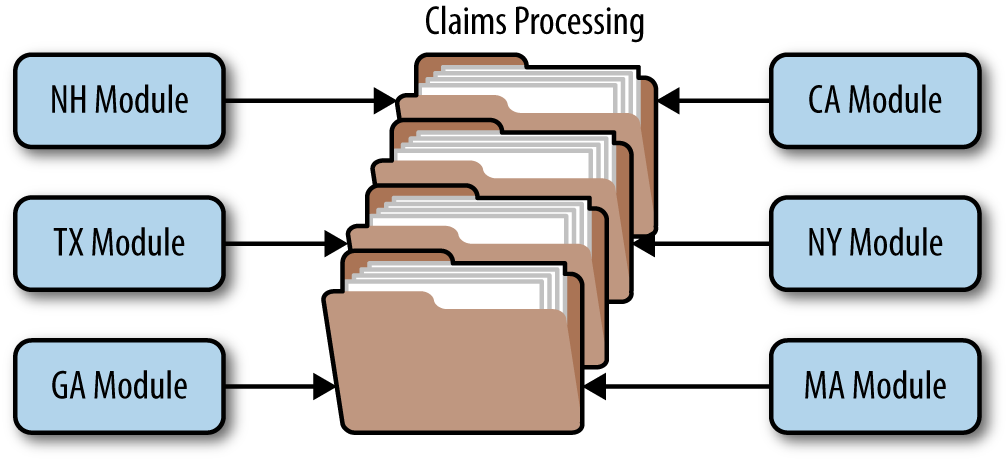

The stack of folders you see in Figure 3-2 represents the core system for claims processing. It contains the basic business logic required by the insurance company to process a claim, except without any custom processing. Each plug-in module contains the specific rules for that state. In this example, the plug-in modules can be implemented using custom source code or separate rules engine instances. Regardless of the implementation, the key point is that state-specific rules and processing is separate from the core claims system and can be added, removed, and changed with little or no effect on the rest of the core system or other plug-in modules.

Figure 3-2. Microkernel architecture example

Considerations

One great thing about the microkernel architecture pattern is that it can be embedded or used as part of another architecture pattern. For example, if this pattern solves a particular problem you have with a specific volatile area of the application, you might find that you can’t implement the entire architecture using this pattern. In this case, you can embed the microservices architecture pattern in another pattern you are using (e.g., layered architecture). Similarly, the event-processor components described in the previous section on event-driven architecture could be implemented using the microservices architecture pattern.

The microservices architecture pattern provides great support for evolutionary design and incremental development. You can first produce a solid core system, and as the application evolves incrementally, add features and functionality without having to make significant changes to the core system.

For product-based applications, the microkernel architecture pattern should always be your first choice as a starting architecture, particularly for those products where you will be releasing additional features over time and want control over which users get which features. If you find over time that the pattern doesn’t satisfy all of your requirements, you can always refactor your application to another architecture pattern better suited for your specific requirements.

Pattern Analysis

The following table contains a rating and analysis of the common architecture characteristics for the microkernel architecture pattern. The rating for each characteristic is based on the natural tendency for that characteristic as a capability based on a typical implementation of the pattern, as well as what the pattern is generally known for. For a side-by-side comparison of how this pattern relates to other patterns in this report, please refer to Appendix A at the end of this report.

- Overall agility

- Rating: High

- Analysis: Overall agility is the ability to respond quickly to a constantly changing environment. Changes can largely be isolated and implemented quickly through loosely coupled plug-in modules. In general, the core system of most microkernel architectures tends to become stable quickly, and as such is fairly robust and requires few changes over time.

- Ease of deployment

- Rating: High

- Analysis: Depending on how the pattern is implemented, the plug-in modules can be dynamically added to the core system at runtime (e.g., hot-deployed), minimizing downtime during deployment.

- Testability

- Rating: High

- Analysis: Plug-in modules can be tested in isolation and can be easily mocked by the core system to demonstrate or prototype a particular feature with little or no change to the core system.

- Performance

- Rating: High

- Analysis: While the microkernel pattern does not naturally lend itself to high-performance applications, in general, most applications built using the microkernel architecture pattern perform well because you can customize and streamline applications to only include those features you need. The JBoss Application Server is a good example of this: with its plug-in architecture, you can trim down the application server to only those features you need, removing expensive non-used features such as remote access, messaging, and caching that consume memory, CPU, and threads and slow down the app server.

- Scalability

- Rating: Low

- Analysis: Because most microkernel architecture implementations are product based and are generally smaller in size, they are implemented as single units and hence not highly scalable. Depending on how you implement the plug-in modules, you can sometimes provide scalability at the plug-in feature level, but overall this pattern is not known for producing highly scalable applications.

- Ease of development

- Rating: Low

- Analysis: The microkernel architecture requires thoughtful design and contract governance, making it rather complex to implement. Contract versioning, internal plug-in registries, plug-in granularity, and the wide choices available for plug-in connectivity all contribute to the complexity involved with implementing this pattern.