Speed matters: Why working quickly is more important than it seems « the jsomers.net blog

The obvious benefit to working quickly is that you’ll finish more stuff per unit time. But there’s more to it than that. If you work quickly, the cost of doing something new will seem lower in your mind. So you’ll be inclined to do more.

The converse is true, too. If every time you write a blog post it takes you six months, and you’re sitting around your apartment on a Sunday afternoon thinking of stuff to do, you’re probably not going to think of starting a blog post, because it’ll feel too expensive.

What’s worse, because you blog slowly, you’re liable to continue blogging slowly—simply because the only way to learn to do something fast is by doing it lots of times.

This is true of any to-do list that gets worked off too slowly. A malaise creeps into it. You keep adding items that you never cross off. If that happens enough, you might one day stop putting stuff onto the list.

* * *

I’ve noticed that if I respond to people’s emails quickly, they send me more emails. The sender learns to expect a response, and that expectation spurs them to write. That is, speed itself draws emails out of them, because the projected cost of the exchange in their mind is low. They know they’ll get something for their effort. It’ll happen so fast they can already taste it.

It’s now well known on the web that slow server response times drive users away. A slow website feels broken. It frustrates the goer’s desire. Probably it deprives them of some dopaminergic reward.

Google famously prioritized speed as a feature. They realized that if search is fast, you’re more likely to search. The reason is that it encourages you to try stuff, get feedback, and try again. When a thought occurs to you, you know Google is already there. There is no delay between thought and action, no opportunity to lose the impulse to find something out. The projected cost of googling is nil. It comes to feel like an extension of your own mind.

It is a truism, too, in workplaces, that faster employees get assigned more work. Of course they do. Humans are lazy. They want to preserve calories. And it’s exhausting merely thinking about giving work to someone slow. When you’re thinking about giving work to someone slow, you run through the likely quagmire in your head; you visualize days of halting progress. You imagine a resource—this slow person—tied up for awhile. It’s wearisome, even in the thinking. Whereas the fast teammate—well, their time feels cheap, in the sense that you can give them something and know they’ll be available again soon. You aren’t “using them up” by giving them work. So you route as much as you can through the fast people. It’s ironic: your company’s most valuable resources—because they finish things quickly—are the easiest to consume.

The general rule seems to be: systems which eat items quickly are fed more items. Slow systems starve.

Two more quick examples. What’s true of individual people turns out also to be true of whole organizations. If customers find out that you take two months to frame photos, they’ll go to another frame shop. If contributors discover that you’re slow to merge pull requests, they’ll stop contributing. Unresponsive systems are sad. They’re like buildings grown over with moss. They’re a kind of memento mori. People would rather be reminded of life. They’ll leave for places that get back to them quickly.

Even now, I’m working in a text editor whose undo feature, for whatever reason, has suddenly become slow. It’s killing me. It disinclines me, for one thing, from undoing stuff. But it’s also probably subtly changing the way I work. I feel like I can’t rely on undo. So if I want to delete something but think I might want it later, I’m copying it to the bottom of the file, like it’s the 1980s. All this because undo is so slow that it might as well not exist. Undo, when it’s fast, is an incredible feature; at any moment, you can dip into the past, borrow something, and zip back. But now it feels like a dead end.

Part of the activation energy required to start any task comes from the picture you get in your head when you imagine doing it. It may not be that going for a run is actually costly; but if it feels costly, if the picture in your head looks like a slog, then you will need a bigger expenditure of will to lace up.

Slowness seems to make a special contribution to this picture in our heads. Time is especially valuable. So as we learn that a task is slow, an especial cost accrues to it. Whenever we think of doing the task again, we see how expensive it is, and bail.

That’s why speed matters.

* * *

The prescription must be that if there’s something you want to do a lot of and get good at—like write, or fix bugs—you should try to do it faster.

That doesn’t mean be sloppy. But it does mean, push yourself to go faster than you think is healthy. That’s because the task will come to cost less in your mind; it’ll have a lower activation energy. So you’ll do it more. And as you do it more (as long as you’re doing it deliberately), you’ll get better. Eventually you’ll be both fast and good.

Being fast is fun. If you’re a fast writer, you’ll constantly be playing with new ideas. You won’t be bogged down in a single dread effort. And because your to-do list gets worked off, you’ll always be thinking of more stuff to add to it. With more drafts in the works, more of the world will pop alive. You will feel flexible and capable and practiced so that when something demanding and long arrives on your desk, you won’t back down afraid.

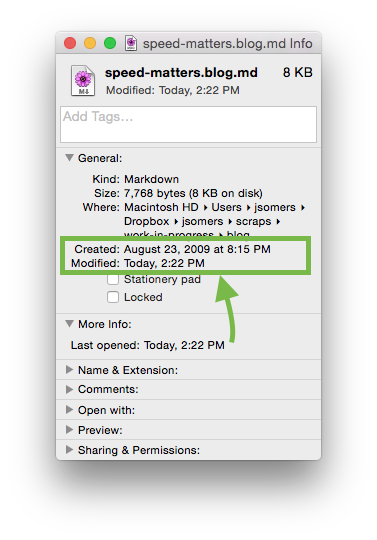

Now, as a disclaimer, I should remind you of the rule that anyone writing a blog post advising against X is himself the worst Xer there is. At work, I have a history of painful languished projects, and I usually have the most overdue assignments of anyone on the team. As for writing, well, I have been working on this little blog post, on and off, no joke, for six years.