How to Hold Your Team Accountable – The Founder Coach

Do you wish your team took more ownership? Here’s how to get your team to the point where you trust them to get the job done without you.

As a CEO coach I’ve heard statements like these many times:

“My VP just isn’t pulling his/her weight”

“I don’t trust him/her to do the work properly”

“My team don’t act like owners”

Sound familiar?

When I first started managing people, I wanted to give as clear direction to my team as possible so they could make their own decisions. But with business assumptions changing on a daily basis, I ended up taking most of the important decisions myself, or even jumping in and doing their work for them.

It put a huge amount of stress on me. Resentment built up and I delegated less and less. With so much on my plate, I was running the risk of burnout, and as my team saw this spiral, they became demotivated . . . and the vicious spiral continued.

How do you learn to trust people and help them step up?

A Simple Definition of Accountability?

There is a simple but enlightening definition of what accountability actually is. And the clue is in the word:

- To be accountable: to provide an account of what’s happening in a particular area.

- To hold accountable: to ask questions about what’s happening in a particular area.

Ultimately, accountability boils down to ‘What happened?’ and ‘This is what happened’. The expectation is that the person holding someone accountable will ask tough questions — and the accountable person knows exactly what’s going on.

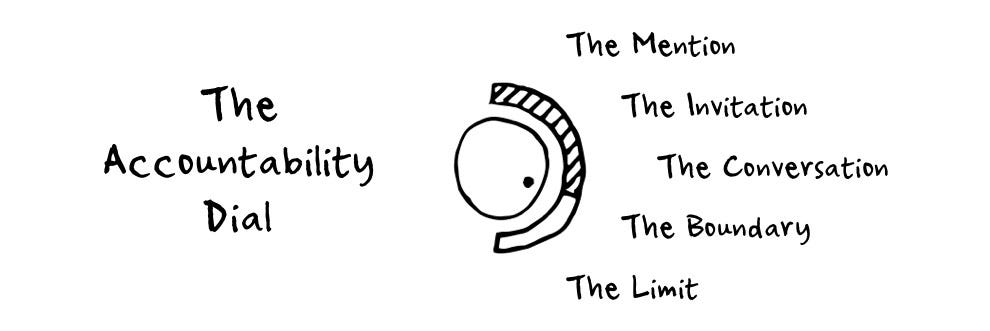

The Accountability Dial

In his book Good Authority, Jonathan Raymond presents a useful framework for holding people accountable, which he calls the ‘accountability dial’. Raymond outlines five different levels of ‘severity’, which are:

- The Mention: Short and immediate feedback where you say what you see and check in early on to make sure everything’s alright.

‘Hey I noticed [a concrete behaviour] . . . is everything okay?’ - The Invitation: An informal chat, usually in private, during which you help someone build more awareness around a particular issue.

‘I’ve mentioned [concrete behaviours] a few times now . . . what’s the pattern here?’ - The Conversation: The ‘we need to talk’ meeting, where you place some urgency around the issue and the importance of dealing with it.

‘[Concrete behaviours] are impacting the team . . . let’s discuss how to resolve this.’ - The Boundary: At some point, you will need to pull rank and outline the consequences of not following through.

‘If [concrete behaviours] don’t change, we may have to consider [possible consequences]’ - The Limit: If the situation requires it, the employee may get one last chance to improve.

‘This is your final warning. Let me lay this out for you . . . ’

Raymond stresses that this dial is not a linear process — it can be turned up and down depending on the situation. For serious issues, you may jump immediately to The Conversation, or even The Limit.

But for many things, a few focused Mentions will do the job. That’s why it’s critical to build real-time feedback into your management style. However, I’m not suggesting you criticise — the ideal Mention is short, light, and comes from a place of genuine concern for the person.

It’s What You Do with it That Counts

The accountability dial is a useful way to start a dialogue and it’s what happens during the dialogue that separates the average managers from the great leaders. The four ideas that follow are among the hardest techniques to master — but they can have a massive impact on your team over time.

1. Ask Open Questions

Asking open questions that require more than just a yes/no response is an essential leadership technique. Whether it’s during a one-on-one, a weekly update, or real-time feedback, the more questions you can ask, the more accountable your team will become.

- What are you trying to achieve?

- What’s working?

- What’s not working?

- What help do you need?

- What resources do you have available?

- What’s becoming clearer to you?

Even requests are more powerful when they’re made as open questions. Consider the difference between these two sentences:

- ‘Please try and arrive on time.’ (a request)

- ‘What will you do to make sure you arrive on time?’ (an open question)

Notice how the second version goes further in helping someone really think through the issue at hand.

2. Weed Out the Excuses

Holding someone accountable can be uncomfortable for both sides. After asking a difficult question, it’s tempting to accept the first answer you get, to ease the tension. However, you must weed out excuses when you spot them.

So what’s the difference between an ‘excuse’ and a ‘reason’? An excuse is a statement of cause that assumes no responsibility. Imagine giving this feedback to a teammate arriving late to the office:

‘Hey John, it’s 10:30 a.m. and you missed the standup — is everything okay?’

John might give one of two responses:

- ‘Sorry, the weather was awful and I got stuck in traffic.’

- ‘Sorry, I didn’t take the weather into account, and I should have sent a message on Slack when I realised I was running late.’

Notice that in the second response, he assumes far more responsibility than in the first. He was aware of his own role in the outcome.

When people realise that there is more they could have — and should have — done to get a better outcome, it can be uncomfortable and they can start to sweat. But as a manager, you can’t shy away from it. Every failure is a learning opportunity.

3. Don’t Solve, Empathise

Resisting the urge to solve the problem will feel unnatural, sometimes even unfair. But it’s important that you get used to it. Not all problems are your problems.

One of the reasons why so many managers jump to the answer is because it can feel really good to solve other people’s problems, especially when they seem easy to solve. But if you’re always playing the hero, you steal the glory from your team.

In the film White Men Can’t Jump, Gloria asks Billy for a glass of water. Billy promptly gives Gloria the water . . . only for Gloria to explain that really, she’s looking for some empathy.

Despite the parody, Gloria has a point. When your team come to you with a problem, it’s a powerful approach to say, ‘Uff, that sounds tough — are you okay?’ rather than jumping immediately to the solution.

Perhaps the most useful question a leader can ask is:

“What will you do about it?”

4. Disagree and Commit

Jeff Bezos coined the expression ‘disagree and commit’ to formalise a manager’s responsibilities to allow teammates to make their own decisions — and be held accountable for them.

Bezos isn’t the only CEO that thinks this way. In his 2018 TED Talk, How Netflix Changed Entertainment, CEO Reed Hastings said:

“I pride myself on making as few decisions as possible in a quarter . . . There are some times I can go a whole quarter without making any decisions.”

This statement got a standing ovation from the TED audience. Every leader knows just how hard it is to allow your team to take decisions that you might not agree with — or that you suspect may fail.

You should even be careful in making suggestions, in the world of accountability. As a CEO, I learned the frustrating fact that what I meant as a suggestion often sounded like a decision to my team. This always came back to haunt me when I held them accountable later and they said, ‘But I was just doing what you suggested.’

5. Outline the Consequences

Holding people accountable and asking tough questions can expose performance issues in an individual. We are all accountable for our own performance. But what happens if, despite regular feedback and conversations, someone’s performance doesn’t improve?

Setting boundaries requires you to define the consequences of overstepping them. It’s helpful to distinguish between two types of consequences: punitive and protective. A punitive consequence is one whose objective is to punish certain behaviours, whereas a protective consequence is one that protects your needs as a business and as a team.

To illustrate, let’s look at the example of someone whose continued lateness to meetings is leaving the team frustrated and inefficient. Which of the following consequences are protective and which are punitive?

- ‘If you keep arriving late for meetings, we won’t be inviting you on the company trip to Barcelona next month.’

- ‘If you keep arriving late for meetings, we won’t be able to afford you the flexibility of working remotely.’

In the first example, following through on the consequence won’t resolve the real issues for the team — those of reliability and punctuality. In the second example, removing the flexibility of work-hours will help protect the team’s needs.

The term consequences can be scary because it’s often associated with firing someone. In reality, there is a wide spectrum of possible consequences, for example:

- Reducing flexibility of work hours

- Switching around roles and responsibility

- A formal warning

- Extra training

- Terminating employment

Where Do You Sit

As the boss, it’s your job to hold your team accountable — even when it feels uncomfortable. It takes regular feedback, coaching, and probing questions to bring out your team’s inner ownership.

Where would you put yourself on the accountability dial? Are you giving real-time feedback and asking enough open questions? Are you empowering and empathising with your team to help them solve their own problems? I invite you to connect the dots. Now . . . what will you do about it?