Martin Fowler

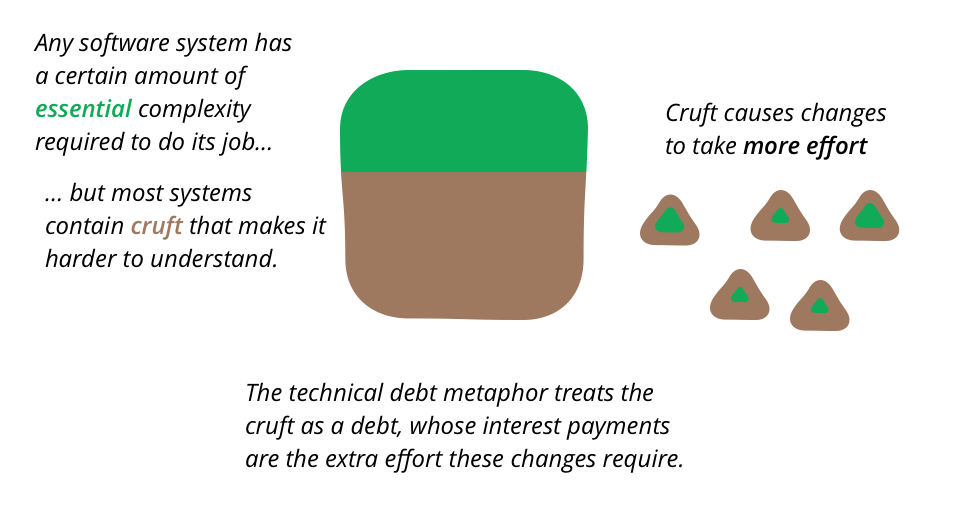

Software systems are prone to the build up of cruft – deficiencies in

internal quality that make it harder than it would ideally be to modify and

extend the system further. Technical Debt is a metaphor, coined by Ward

Cunningham, that frames how to think about dealing with this cruft, thinking

of it like a financial debt. The extra effort that it takes to add new

features is the interest paid on the debt.

Imagine I have a confusing module structure in my code base. I need to add

a new feature. If the module structure was clear, then it would take

me four days to add the feature but with this cruft, it takes me six

days. The two day difference is the interest on the debt.

What most appeals to me about the debt metaphor is how it frames how I think

about how to deal with this cruft. I could take five days to clean up the modular

structure, removing that cruft, metaphorically paying off the principal. If I

only do it for this one feature, that’s no gain, as I’d take nine days

instead of six. But if I have two more similar features coming up, then I’ll

end up faster by removing the cruft first.

Stated like that, this sounds like a simple matter of working the numbers,

and any manager with a spreadsheet should figure out the choices. Sadly since

we CannotMeasureProductivity, none of these costs are objectively

measurable. We can estimate how long it takes to do a feature,

estimate what it might be like if the cruft was removed, and

estimate the cost of removing the cruft. But our accuracy of such

estimates is pretty low.

Given this, usually the best route is to do what we usually do with

financial debts, pay the principal off gradually. On the first feature

I’ll spend an extra couple of days to remove some of the cruft. That may

be enough to reduce the interest rate on future enhancements to a single

day. That’s still going to take extra time, but by removing the cruft I’m

making it cheaper for future changes to this code. The great benefit of

gradual improvement like this is that it naturally means we spend more

time on removing cruft in those areas that we modify frequently, which are

exactly those areas of the code base where we most need the cruft to be

removed.

Thinking of this as paying interest versus paying of principal can help

decide which cruft to tackle. If I have a terrible area of the code base,

one that’s a nightmare to change, it’s not a problem if I don’t have to

modify it. I only trigger an interest payment when I have to work

with that part of the software (this is a place where the metaphor breaks down, since

financial interest payments are triggered by the passage of time). So crufty but stable areas of code can

be left alone. In contrast, areas of high activity need a

zero-tolerance attitude to cruft, because the interest payments are

cripplingly high. This is especially important since cruft

accumulates where developers make changes without paying attention to

internal quality – the more changes, the greater risk of cruft building

up.

The metaphor of debt is sometimes used to justify neglecting internal quality.

The argument is that it takes time and effort to stop cruft from building up.

If there new features that are needed urgently, then perhaps it’s best to take

on the debt, accepting that this debt will have to be managed in the future.

The danger here is that most of the time this analysis isn’t done well.

Cruft has a quick impact, slowing down the very new features that are needed

quickly. Teams who do this

end up maxing out all their credit cards, but still delivering later than they

would have done had they put the effort into higher internal quality. Here the metaphor

often leads people astray, as the dynamics don’t really match those for financial

loans. Taking on debt to speed delivery only works if you stay below the

design payoff line of the DesignStaminaHypothesis, and teams hit

that line in weeks rather than months.

There are regular debates whether different kinds of cruft should be

considered as debt or not. I found it useful to think about whether the debt

is acquired deliberately and whether it is prudent or reckless – leading me to

the TechnicalDebtQuadrant.

Further Reading

As far as I can tell, Ward first introduced this concept in an experience

report for OOPSLA 1992. It has

also been discussed on the wiki.

Ward Cunningham has a video talk where he

discusses this metaphor he created.

Dave Nicolette expands on Ward’s view of technical debt with a fine

case study of what I refer to as

Prudent Intentional debt

A couple of readers sent in some similarly good names. David

Panariti refers to ugly programming as deficit programming.

Apparently he originally started using a few years ago when it fitted

in with government policy; I suppose it’s natural again now.

Scott Wood suggested “Technical Inflation could be

viewed as the ground lost when the current level of technology

surpasses that of the foundation of your product to the extent that it

begins losing compatibility with the industry. Examples of this

would be falling behind in versions of a language to the point where

your code is no longer compatible with main stream compilers.”

Steve McConnell brings out several good points in the metaphor,

particularly how keeping your unintended debt down gives you more

room to intentionally take on debt when it’s useful to do so. I

also like his notion of minimum payments (which are very high to

fix issues with embedded systems as opposed to web sites).

Aaron Erickson talks about Enron

financing.

Henrik Kniberg argues that it’s older technical debt that

causes the greatest problem and that it’s wise to a qualitative

debt ceiling to help manage it.

Erik Dietrich discusses the human cost of technical debt: team

infighting, atrophied skills, and attrition.

Revisions

I originally published this post on October 1 2003. I gave it a thorough

rewrite in April 2019.