Lessons from Keith Rabois: How to be an Effective Executive

published February 24th, 2019

This week’s essay is on how to be an effective executive. This is inspired by a talk Keith gives to some of our portfolio companies’ executives.

Summary

- Running yourself

- Lead, don’t manage: Be proactive rather than reactive. “Lead” your team as opposed to “manage” a situation.

- Understand your output: Your output is how much your team gets done + how much neighboring teams get done divided by how many people are on your team. Only add someone if they bring up the ratio of output to people.

- Focus on inputs: Spend time on judging your team’s inputs, i.e. the quality of ideas, not on whether you can move revenue 3x this quarter, i.e. outputs.

- Spend time on high leverage activities: Do things that have the most impact. Preparing one thing that affects many, like all-hands and dashboards, or do one thing with a lot of impact on one person, like a performance review.

- Optimize your most valuable resource, your time: Actively manage your calendar and audit it by categorizing how you spend your time. Is it on top priorities? Is it on high leverage activities? Show your team real examples of great calendars. Batch tasks. Focus on the limiting step.

- Gather information: Your job as an exec is to make the 4 right calls a year. Can’t do that without all the information so spend time gathering info. Get around filtering mechanisms by wandering the office.

- Simplify the metrics and objectives: Find indicators as close to the inputs as possible. Make those and your team’s objectives as simple as clear as possible. Make sure the team understands the logical jump from achieving that objective to having a large impact.

- Meetings and Decisions: 4 types of meetings, 1:1s, staff meetings, decision meetings, operating reviews. Clarify what type of meeting you are having. Make decisions by knowledge rather than position as much as possible and at as low of a level as possible.

- Peak Performance: Identify whether it is motivation or capability hindering performance. Extend rope to junior people when the downside is low. Always increase their scope.

Part 1: Running yourself

Lead, don’t manage

You need to think of yourself as a producer and a leader driving value, not as a manager. Calling yourself a manager implies some level of reactivity. You manage unexpected situations. You lead to ideal outcomes. You want to be active versus reactive. Driving the vehicle versus a passenger observing. You are judged as a leader by your ability to drive output. Yes, unexpected situations will come up, but that should not be your primary modus operandi.

Understand your output

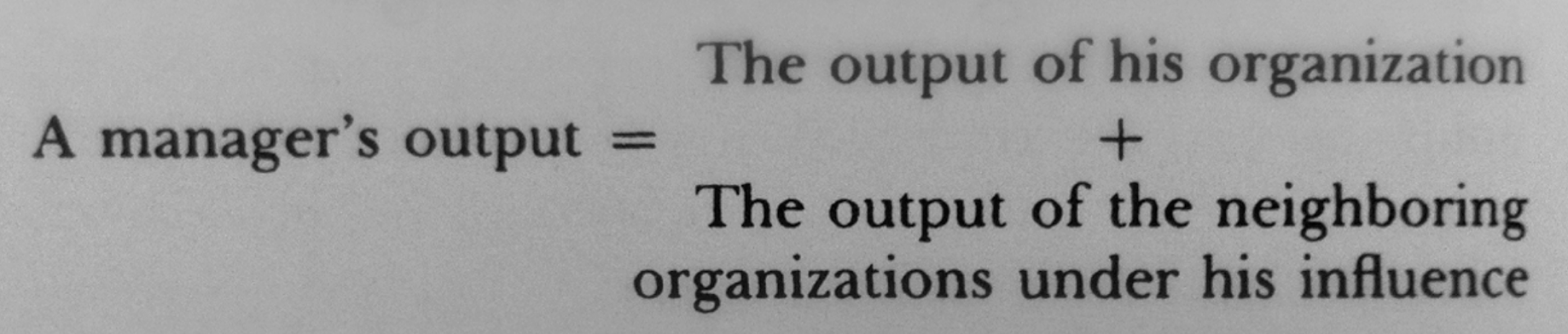

Ok so what does output mean? From Andy Grove (though unfortunate he uses “manager”):

For example, as the head of product, you are primarily responsible for the pace of product releases and updates. You also have a heavy influence on the output of customer support, most of the customers that write in, do so because of a flaw in the product. Your total output as a leader is both product releases and decreasing the number of tickets due to product flaws.

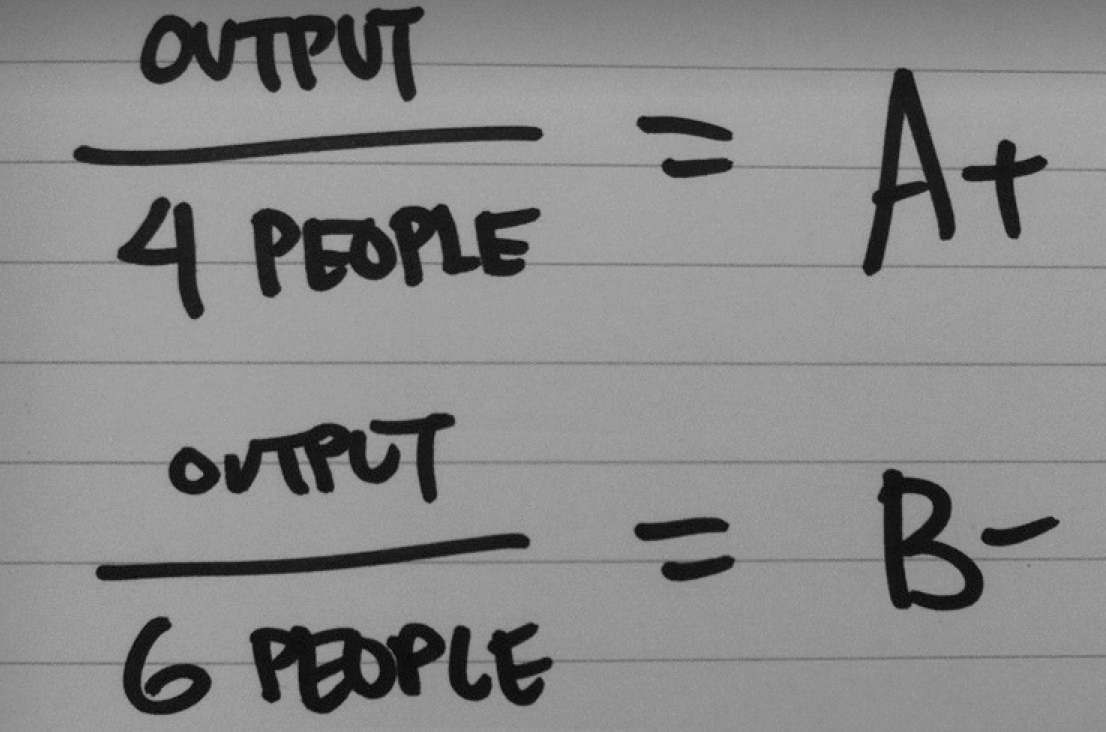

You are also judged as a leader on how many people you need on your team to achieve your output, i.e. your managerial leverage. How much are you able to do with as few people as possible?

This has implications for how you should think about hiring people to your team. People should either individually be so productive that they raise the average productivity of your team, or act as a multiplier to everyone currently on your team. In either case, make sure your overall productivity increase covers the cost of bringing them on. This prevents leaders from arbitrarily hiring into their team for sake of building up a fiefdom. Want to add someone? Sure, go ahead but remember that it raises the bar on expected total per person output.

Focus on inputs

As a leader you do not want to focus on just your outputs, rather you want to see yourself as a function of your inputs to achieve the optimal output. Jeff Bezos spoke at our CEO summit last year and articulated why this was so important to him at Amazon. If you managed people according to their outputs, then your best people will tackle the short-term conservative projects they know will drive outputs to at least some degree. Instead if you manage to their inputs and clarity of thinking, your best people will focus on projects that have the highest potential upside that is explainable, even if they are risky and totally flop. This is part of why Keith hates OKRs; setting your goal to just 3x your revenue over the year will never lead to your best people doing experiments that might lead to 10x revenue increases. Later on I’ll discuss how you can use the clarity of written reports to judge someone’s inputs.

Spend time on high leverage activities

In order to maximize your team’s output, you need to spend time on the activities that will influence that output the most. For example, at Square, Keith would spend at least 5 hours every week preparing for his presentations at the all-hands meeting on Fridays. That might seem like an inordinate time to spend on a weekly presentation, however if he was able to communicate a single idea that affected how everyone at the company made decisions, then it was absolutely worth it.

This is the first category of high leverage activities, when you have many people affected by one thing, spending a lot of time to perfect it is high leverage. Another example in this category is creating your team’s dashboards. Obsessing over the exact layout, font choice, graph types, and colors might seem extreme. However, if it is the dashboard your team looks at every morning when they start work, and what they base their decisions off of, it is critical that it is perfect.

Another category of high leverage activities are when you can have significant impact on a single person. For example, in his first few months at PayPal, Reid Hoffman sat Keith down and told him that Peter Thiel didn’t think Keith was quantitative enough when making arguments. For the next six months, Keith made sure to include metrics in all of his arguments and still thinks about that feedback 16 years later. Being both precise and incredibly candid in your feedback to a single individual can have a massive, and long-term effect and is a very high leverage use of your time.

Optimize your most valuable resource, your time

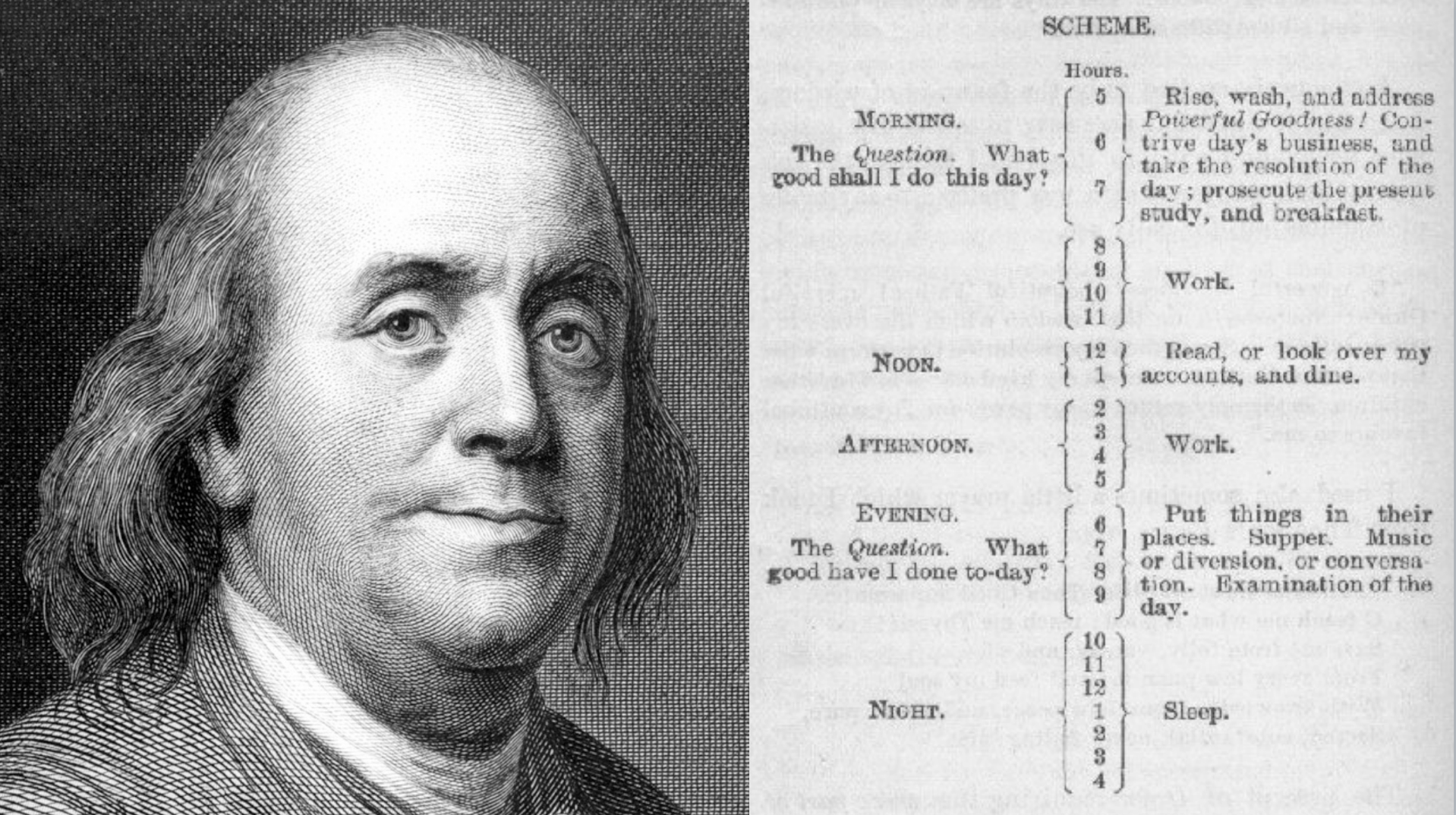

In order to make sure you are doing high leverage activities, you need to literally review exactly how you are spending your time. Even Ben Franklin, before the days of widespread usage of professional calendars, knew that his most precious resource was his time and needed to allocate it proactively.

Keith has noticed that two people with similar education, professional history, and skills can have massive long term differences in success based on how well they utilize their scarcest resource, time.

The calendar interfaces we use today actually exacerbate the problem of not optimizing your time. Most executives are entirely reactive to requests for their time and typically let anyone in the organization put meetings wherever they want on the calendar.

You should instead view your calendar as something you proactively manage and design. Each Sunday afternoon, write down your top 3 priorities for the week and design your calendar to spend 80%+ of your time on those priorities. You can leave some “leftover” time on your calendar to fill with the reactive requests.

For example, almost every CEO that we meet with lists recruiting as one of their top 3 priorities. But if we pull up their calendar, most of them have two 45-min coffees and a single 1:1 with their head of talent. If you’re only spending 2 hours on recruiting, is it really in your top 3 priorities? Managing your time proactively is very counterintuitive and not how most people operate. You need to constantly check back in every week to not let yourself slip into a reactive mode and perform calendar audits on a regular cadence. That means sitting down and going through your calendar for the past month and categorizing each event into your various priorities, as well as identifying how much of your time was spent on high leverage activities.

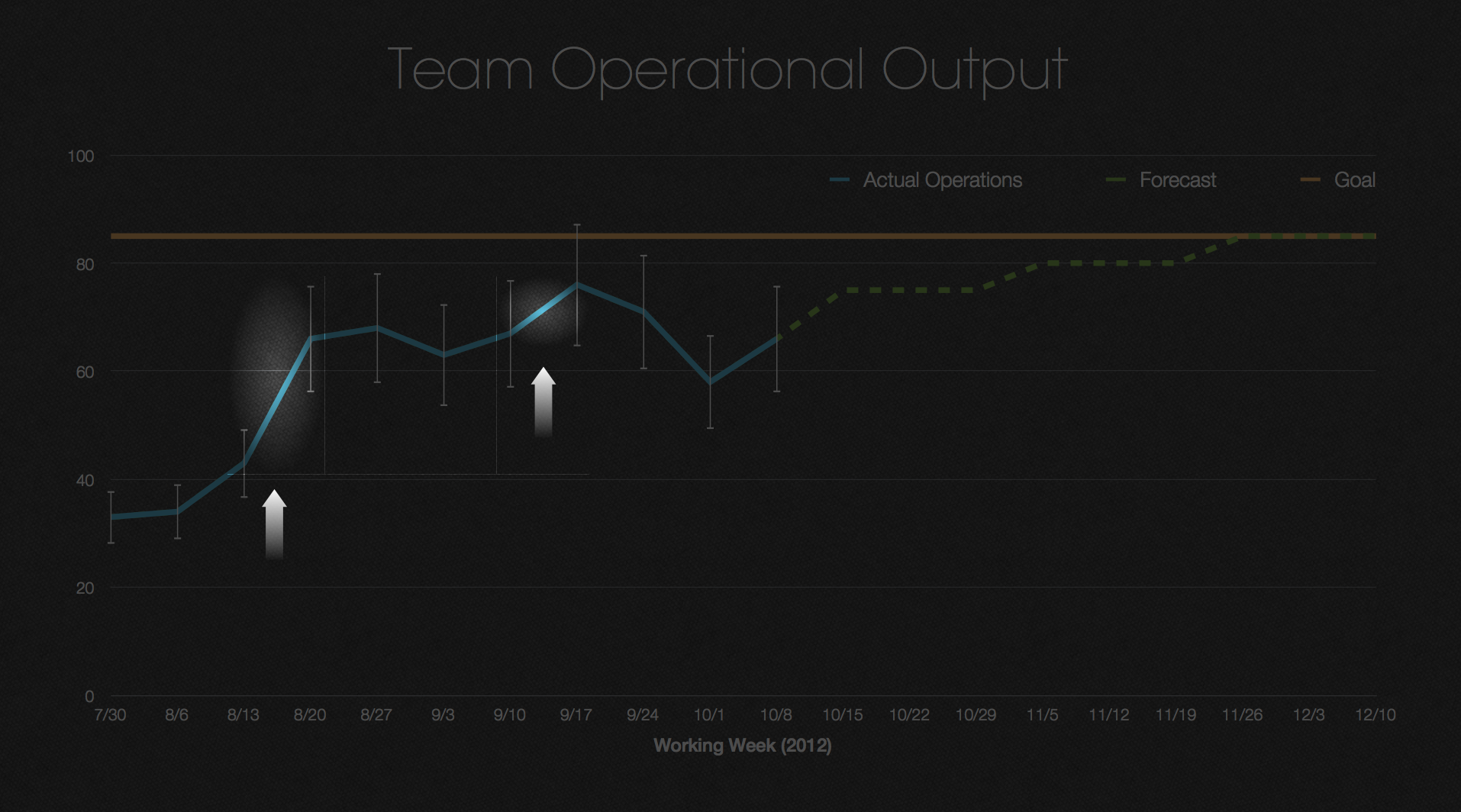

Here’s a real example from back in the days of Square, when a customer success manager did calendar audits on his team for the upcoming week and edited their calendars. Both times, the team saw an immediate jump in their metrics!

There are a few tactics from production manufacturing that you can also use to optimize your time. In any manufacturing line, each step of the process has a different total potential throughput, however the throughput of the entire line is always determined by whichever step has the least throughput, i.e. the limiting step. In order to improve the throughput of the entire line, you have to focus all your efforts on improving your limited step. Any effort dedicated to other steps on the line might help you down the line, but aren’t at all important to work on. Identify the limiting step in your top priority and make sure that 20-80% of your time is dedicated to working on it.

Another tactic from manufacturing you can use is to batch together similar tasks, for example doing all of your 1:1s back to back on the same day. Mostly because context switching is incredibly costly for most people. Paul Graham actually discusses this best in Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule.One thing to keep in mind, is that to be a great executive, you need to reserve time for making and thinking. You have to reserve long, uninterrupted time on your calendar to both think deeply about your strategy, but also for when you are preparing things that affect many people, i.e. an all-hands presentation. For example, Mathilde Collin from Front, said she blocks off 5 hours every Thursday afternoon.

You also want everyone on your team to be proactive about their time management as well. One of the best ways to do this is to present a real-world example of someone on your team who does this well. Walk everyone through an example week on their calendar and point out exactly how they are spending their time. Then have everyone pull out their own calendar and have them go through the same process on their own calendar. Are they batching tasks? Which of the events are high leverage activities? Are there more efficient patterns to create? You should go through this process with your entire team at least once a quarter.

Part 2: Running your team

Gathering information

A critical part of being an effective executive is making the right decision at tough times. Peter Thiel has said that a CEO is largely judged by making the right call about 4 times a year. Doing so without having all the information you need is intellectually bankrupt. Most of your time should be spent gathering information. A lot of that will be fed to you from your direct reports, however any information reaching you is by default going through several layers of filtering. That filtering is not always properly done, so you need to spend time just wandering through your office, picking up on the hallway discussions. You should also meet with skip-levels, i.e. people that report to your direct reports, and get information directly from them. Your goal here is to occasionally tap into the raw information feed of your company, as a sanity-check to make sure no one is filtering something away that is actually very important.

One great way to consistently receive information is to have your team create weekly written reports. Bezos is famous for utilizing this at Amazon with his six page memos. By writing long-form, you are forced to clarify your exact thinking, and it always exposes any logical fallacies you have. Most of the benefit actually accrues to the writer who is forced to clarify their thoughts, as opposed to the reader. For example, when any of our founders and executives are preparing their board decks for a meeting, they almost always end up discovering something about their business in the process of digging into their metrics.

Simplify the metrics and objectives

Your goal is to simplify the information you gathered down to only a few key important indicators. These indicators should act as early predictors to your team’s eventual output. Ideally early enough that you have time to adjust course when they start to veer off, and fix the problem before it affects your output. You almost always want a pairing indicator to prevent your team from overly optimizing to a single goal. For example if you tell your engineering team that they need to ship an update every two weeks, then you need a pairing indicator that measures the number of features they are actually shipping. Otherwise they will definitely ship every two weeks, but the updates to the product will not be a meaningful. A classic example of paired indicators Keith used at Square were fraud loss rate vs false-positive rate. It’s very easy to make sure that you don’t lose any money to fraud if you treat everyone like a fraudster and subject them to tons of hoops and hurdles to send any money. However this is not a good user experience, as any recent user of PayPal can tell you. PayPal would be well served by optimizing a pairing indicator that measures how often they accuse an innocent person of being a suspect.

Beyond just the indicators, you also need to simplify your team’s objective down to a singular goal. If your team tries to focus on everything, they will by default focus on nothing. You also need to have as simple of a logical explanation about why accomplishing this goal will make the biggest difference to the business. High Output Management even has some data which shows that for each step you have to add to this logic, you lose approximately 20-40% of your team’s performance.

This is why it is such a high leverage activity to spend countless hours optimizing the dashboards your team looks at every day. If you can make the logical equation in their head as simple and easy to understand as possible, it can lead to massive performance gains in moving the input indicators and, eventually, your team’s output.

Simplifying both your indicators and your objectives is incredibly difficult. By default you are ignoring indicators and metrics that are true, and other potential objectives which could also be effective. As part of deciding on which to focus on, you should ask yourself, if I could only move one metric, which would it be and why?

Meetings and Decisions

There are a few different types of meetings, and you should explicitly decide which type of meeting you are having ahead of time. Agendas across all these meetings should be set and sent ahead of time.

The first is 1:1s, which Andy Grove originally pioneered through High Output Management. It might sound basic now, but when he introduced the idea of doing regular 1:1s with your direct reports, it was a very radical idea. 1:1s are done for the sake of the junior person, they should be the ones setting the agenda and should ideally focus on giving guidance on performance. Most importantly the junior person should be flagging potential problems as soon as possible. The earlier you know about a problem, the more degrees of freedom you have to implement a solution. One week before launch, there’s not much you can really change.

The second is staff meetings, meaning you meet with all of your most senior leaders. Claire Hughes Johnson has given the defining talk on this topic and I would highly recommend listening to it here. Your staff meeting should have a predefined agenda that covers a range of topics, each of which should affect at least two people. You should also decide ahead of time how you and your staff will make decisions, for example you can be democratic (majority vote rules), consensus (everyone has to agree), or autocratic (most senior person makes the call).

The third is decision meetings, which is a subset of what should happen regularly in your staff meetings. When a particularly major decision needs to be made, you can gather your team to discuss what the final call should be. Even if you do democratic or consensus, you should always stick to the “Peers Plus One” model, meaning that there is always one person in the room that is the most senior. This can make sure there is someone responsible for things not getting “stuck” if everyone has equal power. That person doesn’t necessarily have to drive the conversation or even participate as long as things are moving along.

The fourth is operational reviews. In this meeting a functional unit should be presenting their progress, and their peers across other groups should provide feedback and suggestions. These should act as mini-board meetings for particular groups and should occur at least once a quarter for major teams.

There are fundamentally two different ways to make a decision between two people. “Position”, meaning I am the most senior person, so I make the call and “Knowledge”, meaning I am the person with the most knowledge about the situation. It’s perfectly reasonable to overrule a junior person who is closer to the metal on something, but if you do so, you need to be responsible for understanding all of the inputs into that decision. Recognize though that you burn a certain amount of social capital each time you overrule a more junior person purely through position. If you do this over and over, instead of explaining the underlying why and shifting to a knowledge-based decision, you will eventually burn your best people out.

Ideally all the decisions being made in your organization should be made at the lowest necessary competence level, and are only bubbling up to you if your expertise is needed.

Peak performance

If you still feel like you aren’t getting the peak performance from a team member that you expect, here’s a final framework that can help. First, ask yourself whether this person is capable of doing the work you want them to do if their life depended on it. Is it a question of motivation or a question of capability.

If their life depended on it and they could do it, then that’s on you as a leader not providing the proper motivation. Most of the time that’s due to you not providing the larger story as to why their work is meaningful and the impact they will have. Per Goethe – “Dream no small dreams for these have no power to move the hearts of men.”

If however, they would be unable to do it even if their life depended on it, then that is your mistake as a manager for expecting them to be able to. Someone’s ability to do a particular task is called “task-relevant maturity” which essentially means how much experience does someone have doing this task.

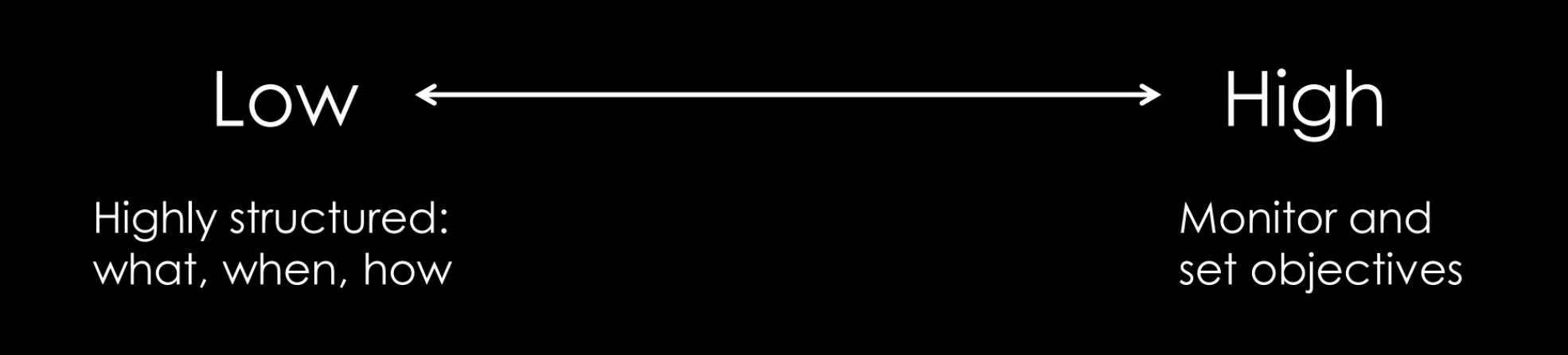

If it is low, then you need to be incredibly structured and micromanage the employee as they accomplish a task. If they have done this task many times, then you can be far more laissez faire and just check in occasionally. This implies that your method of management is determined by the employee you’re managing, not by your particular preference or style. This is also a great way to interview an executive, if you do reference checks on prior direct reports that they’ve had, ideally half of them will say she was a micro-manager, and half will say she’s very laid back.

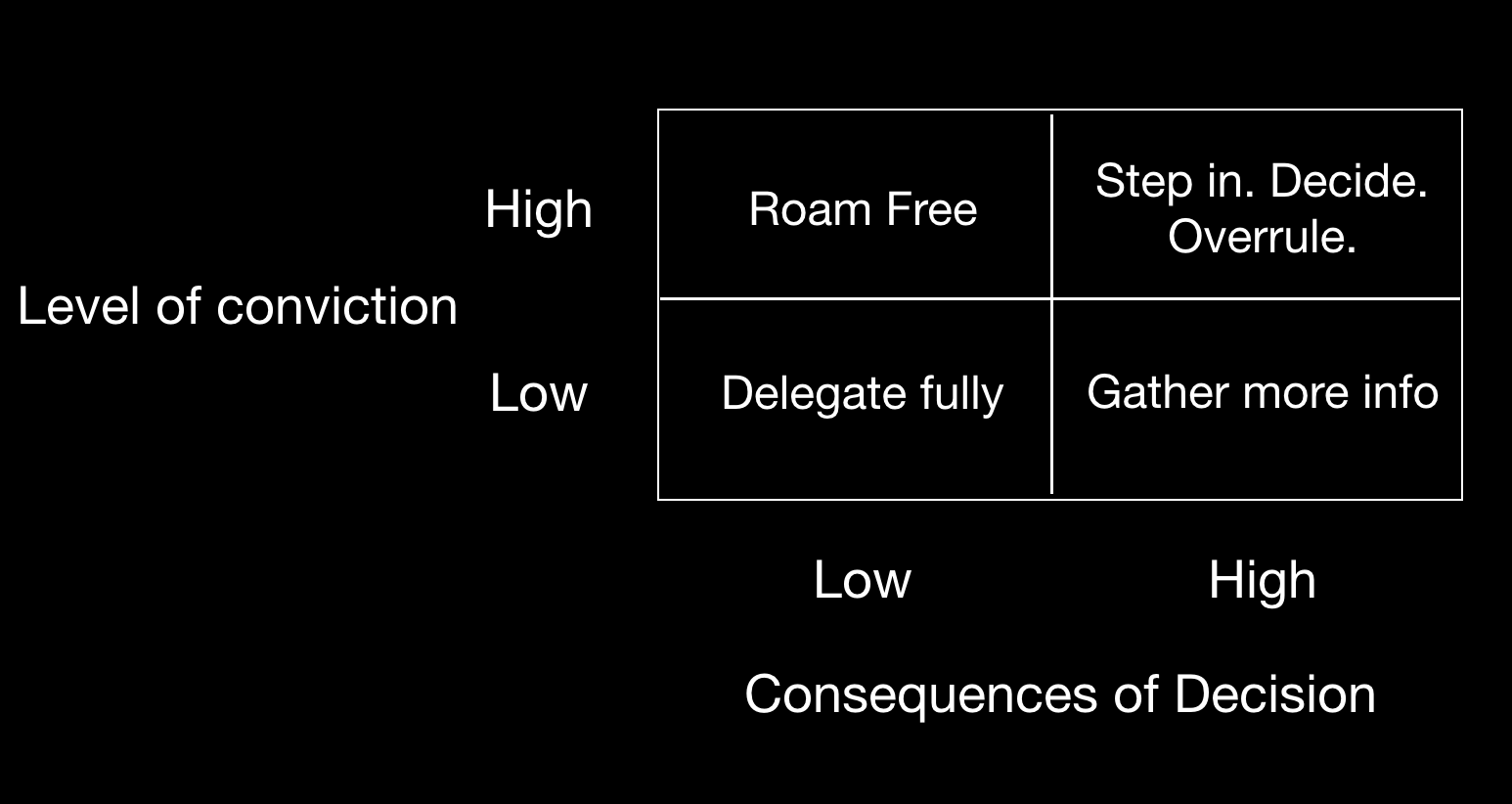

Ideally, over time you are teaching your direct reports and extending them enough rope on decisions such that they are learning to make their own judgments over time. On any particular project or decision, you can sort it by the following variables: Your conviction, i.e. do you think you know the ideal right answer or best final product, and the consequence, i.e. if you make the wrong decision or ship an imperfect product, are there catastrophic downside.

If both are low, then just delegate the project fully. If your conviction is high that you know the perfect solution, but your junior person disagrees, it’s much better to let them go off and ship what they want to ship, as long as the consequences are low. You want to extend them rope to implement their own ideas and learn judgment on their own. On the other hand, if the consequences of a decision are high, you need to either have high conviction and overrule your junior teammate, or you need to ask them to go out and gather more information until you have high conviction about a decision. You can’t wait until you get to 100% confidence on these types of decisions or else you will move too slowly, the ideal level is around 70%.

By extending junior people’s rope when the downside is low, they will gain task maturity and be able to handle more complex situations in the future. For example, one of my high potential seed investments was going out for a Series A last year. Keith let me handle the negotiation for the round, which was the first time I was doing so on my own for that large of a round (I had only done seeds on my own to date). However, the consequence was relatively low here since we already had decent ownership in the company, so even if I botched it, it wasn’t like we were going to end up entirely missing the company. In the end, I did totally botch the deal and we lost the A to another highly qualified firm for a variety of reasons. Keith extending me that rope taught me a lot and just a few months later I was able to close a promising Series A on my own.

You should be constantly expanding every team members scope until they reach their breaking point. Everyone has one, no one can run the whole world. Your job is to discover everyone’s individual breaking point. Then pare back and teach them how to handle more.

Thanks to Lachy Groom, Evan Moore, JD Ross, Owen, Matteo Franceschetti and Ryan Orbuch for helping with this one

Here is the presentation Keith uses