Winners and losers of the subscription frenzy (1/2)

The internet for news is closing. In the wake of the global failure for digital advertising, publishers are putting their hopes in subscriptions.

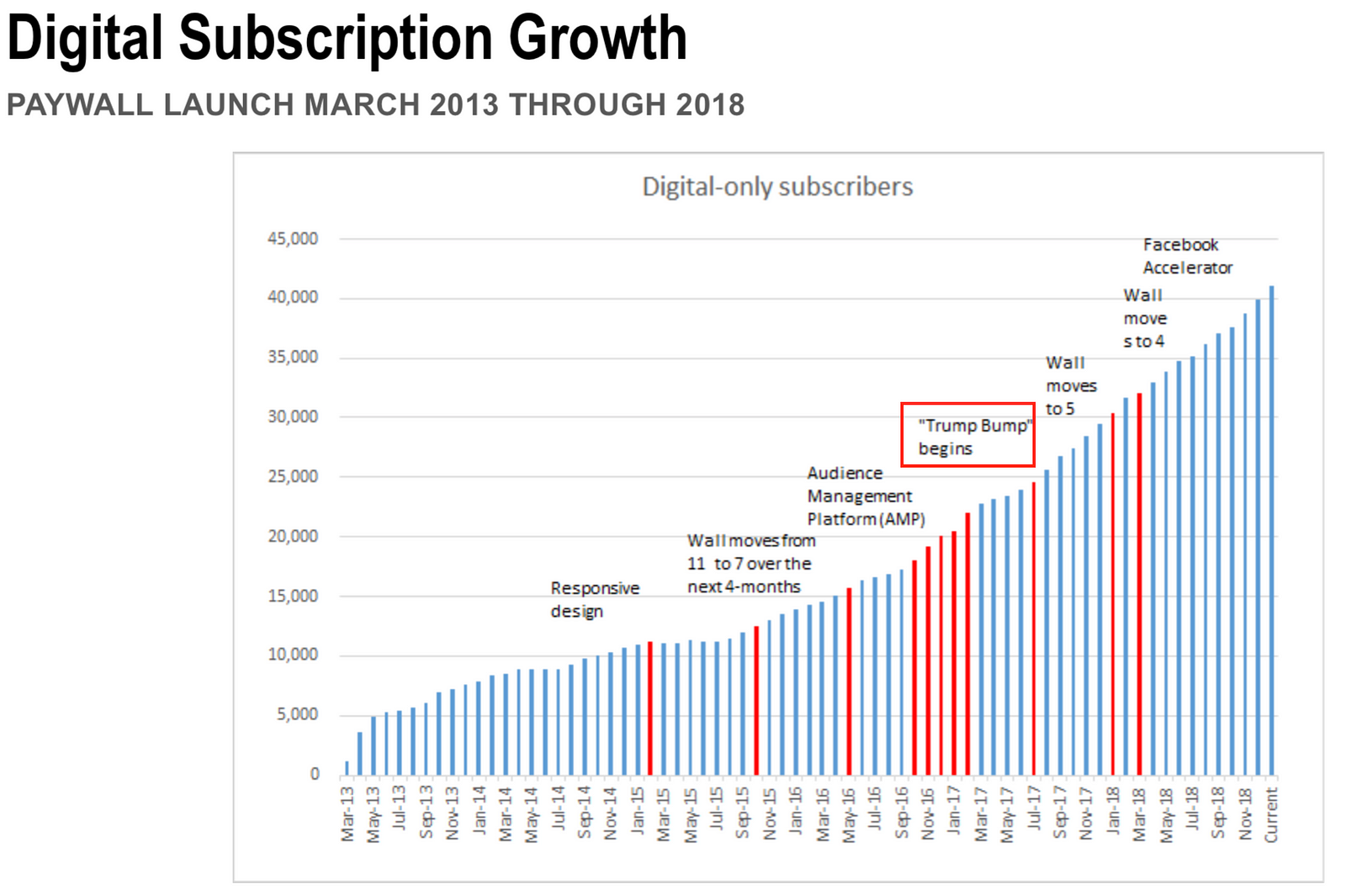

Three weeks ago, at a Digital Subscription conference hosted in Paris by WAN-IFRA, I asked Alan Fisco, president and publisher of the Seattle Times how he felt about the “Trump Bump” in the digital news business. “It is one of the things that keeps me up at night”, he replied. The Trump effect had a positive impact on The Seattle Times’ digital subscription portfolio as shown here:

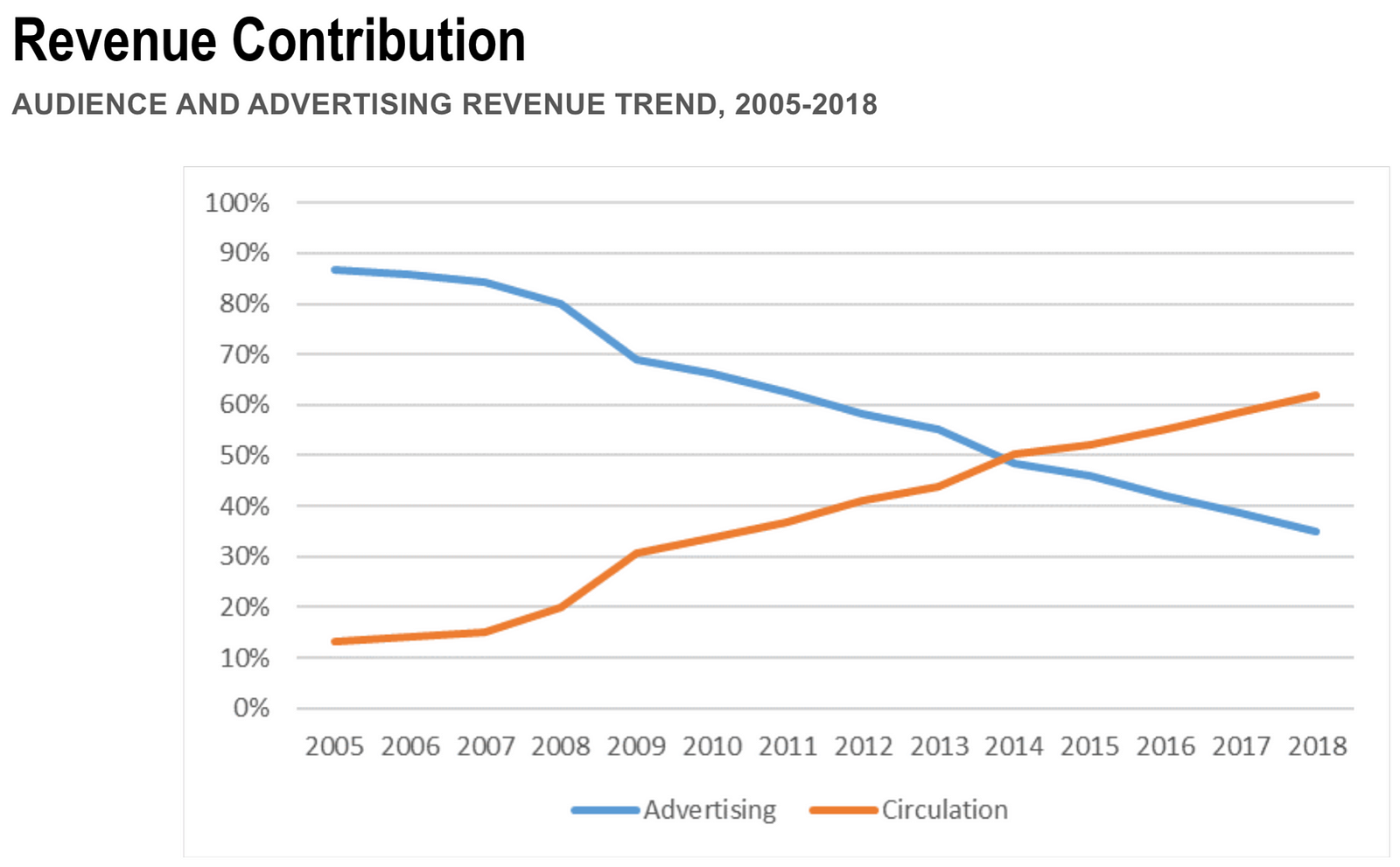

Since the 2016 election, the ST digital subscribers have grown 2.3x while the publisher took multiple steps to recruit and retain paid-for readers, investing in technology, data analysis, and Customer Relationship Management. As a result, the paper has been able to drastically change its revenue model. In 2005, the ratio of advertising revenue over circulation was 90/10 percent. Now it is 38 percent for ad and 62 percent for circulation:

Among the recent converts to a paywall, the Pacific Northwest media should not worry too much about the sustainability of its business model: it retains a firm grip on two important audience drivers — local news and sports. It also never cut corners in journalism. It collected 10 Pulitzer Prizes, recently launched an investigative fund and remains an excellent source in aerospace and tech news.

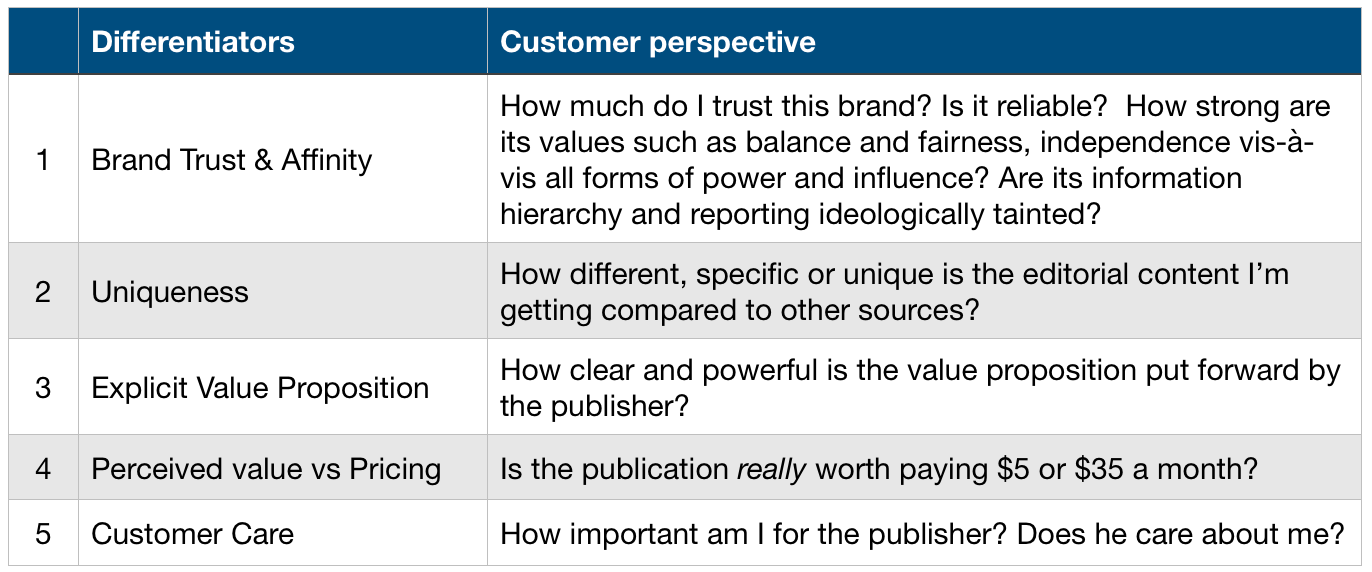

In short, the Seattle Times has preserved two key elements in modern news economics: uniqueness and value proposition.

Here are the differentiators for successful subscription models:

1. Brand Trust & Affinity. These are the primary motive for a reader to consider a subscription. Unfortunately, trends in the industry blur these notions: with nearly half of the users getting their news from social platforms, the proportion of people able to remember the name of an original source of information is dwindling. It is the worst damage inflicted by the platforms: Facebook, WhatsApp, Google News have diluted the notion of brand — as well as the notion of authorship — the two pillars for trust in the news. Apple News is better at showcasing brands in its interface but its destructive business model — and the “Spotify for News” fantasy — are killing the economics of the news business. Restoring news brands should be the first move of the industry.

2. Uniqueness. This is the prime factor to convert a regular user into a paid one — but it is still largely overlooked by publishers. A media able to convince a reader that it is the only one to provide a specific content / angle / breadth and depth in its coverage is in a much better position to ask for money than the owner of an “everything news store”. Readers who want exhaustivity go on social, look at aggregators or create their own channels.

This should lead some publishers to reconsider the very nature of their output. Right now, a large media outlet such as a national newspaper that churns out 200 stories a day will admit that only 15 to 20 percent of them can be labeled as truly value-added, resulting from decisive journalistic choices, robust journalistic legwork, profuse sourcing, etc. The rest is what is called “commodity news”, necessary for the sake of an alleged need for exhaustivity but deprived of specific news and monetary value. Very few newsrooms management, fearing internal fiefdoms feuds, are ready to revisit this principle. Asking a reader to pay for the vague claim of better quality is no longer an appealing promise. Exposing what you are the best at, is a powerful statement.

3 . Explicit Value Proposition. Statements from the most successful publishers are clear about the benefits to the readers: “We save them time”, (The Economist); “The reader gets value from the news we provide” (The FT). When looking at it, few publishers are good at summing up their differentiator in one short concept. A reader who has the choice in a flurry of $10-$15 a month offers, but the discretionary income to pick-up only two, wants more than a vague promise.

4 . Perceived Value over Pricing. In short, the question asked by the customer is: what do I get for my money? For some, a weekly newsletter about the airlines economy produced by a former industry CFO, with original analysis, and /or a clever curation, will be worth thirty bucks a month. In other instances, a subscription to a news service of good quality will lose its value as its content tends to show up elsewhere. For instance: a good story from the WSJ.com or the FT.com is likely to be picked up by countless free publications. In an era of quick decay of information, the value of the subscription lies elsewhere. For example in the early access to the original and unfiltered information; or to multiple features provided by the publisher’s interface: context, details, related stories, multimedia elements, recommendation engines, and personalization systems.

5 . Customer care. This is the least considered element to retain a customer and where the old and new world collides.

At one end of the spectrum, you have publishers like Le Monde who ask for a registered mail to unsubscribe or The Information (the tech website of the Valley) which sternly replies (in substance) “Read the fine print, moron” when you protest about an unwanted extension of your subscription at a major price hike. This kind of behavior conveys a weak message by saying: “To meet our goals and because we are not sure about the ability of our product to keep you onboard, we need to lock you at any cost”. As a customer, you bite the bullet and put a reminder in your calendar to cancel you sub in due time. When you do so, you get an automated reply asking “Would you stay in exchange for a $100 discount?”, then you wonder about the real value of the service. And quit, for good.

Fortunately, when it comes to express some consideration to the client, the tech world has reset the clock. They did so by relying on the right metrics. When I say to Amazon, “I didn’t receive this item”, I’ll get a refund, no question asked. Why? Because, I’m a long time customer, with a significant ARPU, and, more importantly, a high-reliability score (I don’t abuse the system). Other chose to let the subscription door open, like Netflix which I can leave and come back as I wish. This tactic carries several virtues:

— The customer enjoys a sentiment or trust and freedom.

— Internally, the inherent fragility associated with a come-and-go subscription system keeps everybody on edge: the people in charge of the subscription system of course, but also the product team — as long as the notion of customer percolates in every layer of the company. No one rest on their laurels.

Right now, the news industry is reluctant to consider anything beyond the lock-up-the-customer-model. But things change. According to a Guardian exec who spoke at the Perugia Journalism Festival this month, the newspaper does not rule out opting for complete freedom for its subscribers. It would be a revolution in the business and a smart move from The Guardian whose paid-for customers represent a mere 0.6 percent of its global audience.

. . .

In the next Monday Note, we will talk about best and worst practices in the subscription business, from sophisticated data miners to those who poison their business by adding subscribers that carries no value.