“The Linux of social media”—How LiveJournal pioneered (then lost) blogging

Last April, famed writer and hero-murderer George R.R. Martin announced that he was hoisting his ancient blog from his moldering LiveJournal onto his personal website. For casual Game of Thrones fans, it was a minor hiccup at best—most clicked the new link and never looked back. For a certain strata of enthusiasts, however, this was a far more momentous move. Described as “the last holdout” by longtime LiveJournal volunteer-turned-employee Janine Costanzo, Martin’s blog was perhaps the once-blogging-giant’s last bond to the world of great pop culture. So while the author may never finish his most beloved literary series, his simple act of Web hosting logistics truly marks the end of an era.

Growing up on the Web at the dawn of the social media age (circa 2007), it felt like all the connectivity-obsessed sites forming the burgeoning core of the new Internet were haunted by a faded spectre called LiveJournal. As a teen, I never actually knew anyone who had one, but I heard whispers and rumors about drama on the service all the time. And based on candid conversations with some of the figures who made LiveJournal what it was, it turns out that impression isn’t far off. LiveJournal, or LJ, as its users lovingly called it, was a different kind of social media service, one that is almost unrecognizable in a world dominated by the anonymity-shattering power of a Facebook or Twitter. But, as many of its former employees attest, LJ ultimately had the opportunity to become one of these “second-generation” social behemoths. Instead, a stubborn userbase and questionable business decisions harried those ambitions. And now, Martin’s latest figurative casualty—the severed LiveJournal—serves as a brief reminder of the platform’s ascendance and the decisions that brought this blogging icon crashing down.

Built from the dorm

Like many eventual household names in tech, LiveJournal started as a one-man project on a lark, driven by a techy teenager with too much time on his hands. As founder Brad Fitzpatrick recalls, in 1998, after getting kicked off America Online for messing with its service too much, he managed to convince a local ISP to enable his personal website to use the Common Gateway Interface protocol. The move allowed him to write custom scripts that would produce dynamic objects on his page, such as his exact age in seconds, counting ever upward with each refresh. The novelty of these dynamic objects astounded Fitzpatrick, to the point that he eventually made a one-line textbox that floated above his desktop’s Start bar so he could type in and post to his site.

“It didn’t even have a post button,” Fitzpatrick recalls. “It was just the Enter button. My early LiveJournal posts were stuff like ‘going downstairs to get a Coke,’ or ‘I’m bored.’ It was very much like early Twitter.”

After giving the script to a handful of friends, Fitzpatrick realized that every update he made meant that he’d have to hand it out all over again, so he let his friends piggyback off his server for ease of use. When Fitzpatrick soon went to college at the University of Washington, the script spread with him. He eventually got his entire floor of his dorm posting, along with friends in different states. The service grew organically from there.

These handful of early users shaped the functionality of the site with their behavior. For example, when friends started complaining about the unsheared “walls of text” that some of their peers would post, Fitzpatrick added a “post” button so they could space out their paragraphs. There was no way to respond to other people’s output initially, no matter how insipid—until, of course, Fitzpatrick decided that he wanted to make fun of one of his friend’s posts. He next added in the comment functionality just to post “a snarky-ass comment.”

“Everything was like that,” Fitzpatrick says. “Current mood, current music, profile pics—it was all screwing around and trying to add whatever new things we could do or what the Web supported at the time.”

At a certain point in his college career, around the year 2000, Fitzpatrick realized that LiveJournal had turned from a fun way to mess around with CGI scripts into something approaching an actual business. “At that point,” he recalls, “the mission became: keep the damn thing alive.” So, as he approached graduation and the popularity of the site continued to mount (plus the cost of the servers kept spiraling ever upward), he began to wonder if he needed to hire some people to help him keep the site from falling over every week.

That’s when he met Lisa Phillips, a systems administrator at a local DSL company in Seattle. She happened to make a LiveJournal post right as Fitzpatrick was trying to move his embattled servers out of his dorm room. “A bunch of us were LiveJournal users at the company,” says Phillips. “So, I just reached out to him and said, ‘I don’t know you, but we have room.’ It was literally a rack in a closet, but we had room.”

Needing to hire a full-time sysadmin, Fitzpatrick approached Phillips with the job in 2001. Because they were both 21 at the time and he had never hired anyone before, Fitzpatrick brought his dad along to help construct something approaching a formal interview process. “It was surprisingly professional,” Phillips says. “And I got the job. I was the first person paid to work at LiveJournal as a sysadmin for the entire site.”

-

LiveJournal shortly after being started in 1999.

-

LiveJournal in 2003 as the service boasted around one million users.

-

LiveJournal in 2008, post-sale. (Note the front page shoutout to ONTD.)

-

LiveJournal currently—it lives! (The site enjoys its most popularity in Russia these days.)

-

…and 2018/2019 LiveJournal kinda, sorta resembles reddit in its front page.

As Phillips recalls, keeping LiveJournal online at the time was a 24-hour-a-day job, with brutal hours and an ever-expanding nexus of responsibilities. (Within the first two years following Phillips’ hiring, LiveJournal eclipsed the one million user mark—years later, after social media had become more commonplace, that same feat took Twitter nearly two years as well). Fitzpatrick and other early LiveJournal programmers lived in Fitzpatrick’s hometown of Beaverton, Oregon, but the site’s servers were nestled in downtown Seattle with Phillips—three hours away. It naturally fell to her to perform the very physical data center work of “racking and stacking” systems and servers to make sure that the site would run well (or, at least stay online). And since Fitzpatrick was her only backup, and the site continually ran over capacity, Phillips essentially stayed in contact with him every day, to the extent that she would text him if she was going to a movie for a few hours. Despite the arduous conditions, she believed in the mission of LJ, and that kept her going through long weekends and evenings.

“All the companies I worked for were about the excitement and opportunity of what it would be like when you could form communities without the limitation of the physical,” she says. “I remember I was having a very rough week, and I was saying I should quit and go work at a pizza place, or something like that. And my sister-in-law told me with tears in her eyes that LiveJournal saved her life. She was a new mom, she had this community of new moms who are living in communities that are really homogenous, and they were a community of moms that are liberal and tattooed and have different ideas than our community. She said it can be lonely being a mom, and having access to these communities are the only things that kept them together. She said if I hadn’t been doing the work to keep it alive, she didn’t know what her life would have been like. And that kept me going.”

Growing pains

As the site grew well into the ’00s, the amount of volunteers that both educated new users and policed the site for toxicity swelled. Once again, concerns over the company’s sustainability began to dog the site, especially in regard to the founder’s ever-expanding list of duties. While he only really wanted to build features for the site, he ended up balancing as many hats on his head as he could manage: responding to user emails, negotiating hosting contracts, and trying to shore up the budding platform’s income streams, for instance. “I was bad at delegating, and I was constantly on the verge of burning out,” says Fitzpatrick. “It felt like every day I was bouncing around fighting whatever fires there were, since we were all pretty much programmers there.”

With the core dozen-or-so LiveJournal staff consumed with merely keeping the site afloat, it often fell to the volunteer support staff to set site policy. And this structure could sometimes cause the fires to flare up even more.

“The problem with the site was that we were a very young group, and nobody had any experience with project management,” says Denise Paolucci, who led the volunteer support team at LJ for several years (she later co-founded the Livejournal code fork Dreamwidth). “We were just making it up as we went along. I think Brad [Fitzpatrick] just wanted to program. We had problems in those days because what got fixed was based on who yelled the loudest at Brad most recently. Friends would tell him about a problem that they were having, and he’d try to fix it. But as it turned out, maybe the support team had been asking for that little change for a long time, and the volunteers would feel frustrated, because they wanted it done slightly differently. If we didn’t implement things in exactly the way that users had been asking for, we’d have problems.”

Eventually, Fitzpatrick tired of the pseudo-management role he had unwittingly thrust upon himself and sold his company (called Danga) to Six Apart in early 2005. At the time, Six Apart was a small software company best known for authoring the blogging software TypePad.

In retrospect, Fitzpatrick says concerns about the increasingly competitive business landscape around proto-social media sites like WordPress (established in 2003) and Blogger (around since 1999) also contributed to his decision. (For an idea of the greater landscape: Facebook was founded a year earlier in 2004; Twitter would follow in 2006.) But at his platform’s height in the mid-aughts, LiveJournal was a titan of blogging, boasting over ten million accounts. Multiple people Ars spoke with gestured to the site’s largest community, the celebrity gossip page “Oh No They Didn’t” (ONTD) as a beacon of the site’s influence. As former LiveJournaler Abe Hassan puts it, even as larger social media platforms began to outgrow them, celebrity deaths would still bring so much traffic to ONTD that the site would crash, starting with Heath Ledger’s tragic end in 2008. The page also broke several big-ticket (but now forgotten) tabloid stories of the era, including Jamie Lynn Spears’ pregnancy (news of which was later picked up by larger outlets).

As early employee Janine Costanzo remembers, staff sentiment surrounding the acquisition was high. Some hoped that Six Apart would be able to provide a robust roadmap for keeping the service alive for the long haul. Better yet, the capital infusion allowed the company to hire longtime volunteers like Costanzo and Hassan as full-time employees, which helped boost morale. But as time went on, it became apparent that the paymasters at Six Apart didn’t quite understand how to navigate the calcified core of LiveJournal users that reared back at every change that the company wanted to make, especially when it came to cash flow.

Multiple subjects point to a particular kerfuffle as an example of LiveJournal’s rowdy userbase in action: a 2006 controversy over bare breasts in user icons that the employees dubbed their “Nipplegate.” According to Paolucci, it all started when a trollish user set their default user icon to a picture of The Golden Girls’ Bea Arthur photoshopped on the head of a naked woman. Since your default icon was used in search indexing, the site-wide policy disallowed nudity on it, though it was fine elsewhere. The team asked the user to remove it—but instead of complying, the user decided to start reporting any nudity he saw on fellow user icons, many of which belonged to a pro-breastfeeding group that liked to exhibit their children breastfeeding as part of their icons. The LiveJournal team recognized this behavior as malicious reporting, but they felt handcuffed by their own rules. Soon, the breastfeeding groups were asked to remove their icons as well, resulting in a national PR nightmare for Six Apart. At least one major activist group protested outside their offices.

Hassan says it was a shock for the employees of Six Apart, especially those who weren’t devoted LJ users. “It was in our weekly company meetings, and we’re reporting on this new policy, and whether or not you can show the areola,” he says. “The rest of the company had not engaged with this. They were used to selling to businesses, not dealing with the chaos that a direct userbase can bring… Today, on Facebook or Twitter, everything is a form response, or an auto-response. But early on, we set the expectation that if you wrote in to us, you would get a personalized response. We should’ve been more severe. We didn’t have that level of nuance in our policy. It was like, are breasts OK? No, then, done. We should’ve taken more of a stance on what ‘sexualized’ meant, and moved in the direction of community standards, like what [image sharing site] Flickr had, rather than freedom of speech.”

Hassan’s response echoes a common refrain of these one-time LiveJournal employees: the inertia of user expectations could become almost impossible to overcome. For instance, soon after Six Apart bought the company, a conveyor belt of project managers were brought on to try to harness the chaos of the company into something more profitable. These new analysts took aim at the site’s freemium model, only to be stymied by the weight of past promises. “We were always saying that we were fighting for the users, that we would run everything by the community before we did anything,” says Mark Smith, a software engineer who worked on LiveJournal and became the co-creator of Dreamwidth. “Well, as it turns out, when you do that, you end up with the community telling you that they want everything to stay the same, forever. We had promised to never include ads on the site, and all of a sudden we have our new management telling us, ‘The site needs ads, the site needs ads.’ It was an impossible situation.”

Paolucci sums it up best: “Back in 2007, at the height of the burnout phase, when we were all going for the gallows humor, we joked that we would post in the news journal that we were giving everybody $100, a pony, and a latte, and the first five comments would be people objecting that they couldn’t have caffeine, somebody saying they were allergic to ponies, and somebody going to a screed about how free money is the root of all evil in society,” she recalls. “It was black humor, but it was kind of true. There was an antagonistic relationship between the ‘power user’ and the people emotionally connected to the community versus the people making decisions for the product. There was no trust in either direction. That antagonism is really what doomed it.”

A changing landscape

The tumult at LiveJournal, of course, didn’t happen in a vacuum. New entities started entering the blog wars, and competitors like Tumblr began to siphon market share from LJ into the late ‘00s. LiveJournal exodus seemed to be triggered in part by actions like the mass banning of several figures in the X-rated Harry Potter fanfiction community under pressure from religious groups (ostensibly for writing erotic stories about underage characters). And as incident gave way to incident and pressure began to mount, employees began to leave the company. Six Apart eventually sold LiveJournal to Russian company SUP Media in 2007.

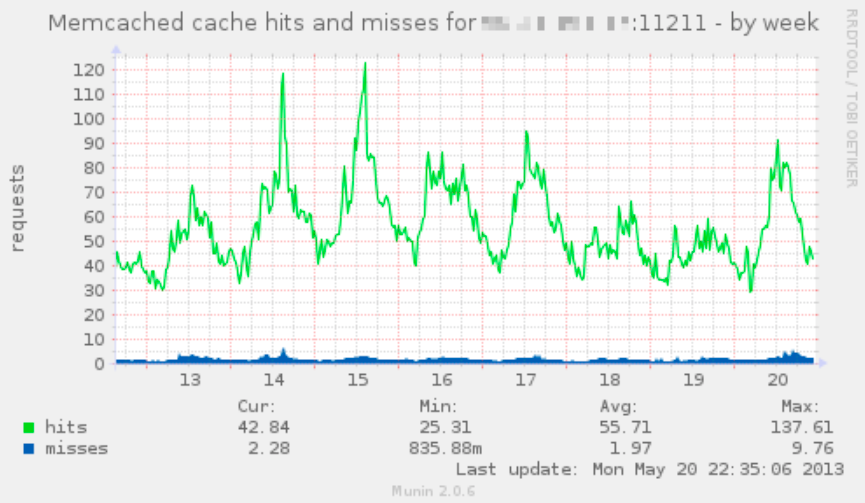

Thanks to its US-based servers, LiveJournal had proven extremely popular in Russia since the platform’s launch—so much so that it became the country’s standardized word for “blog,” similar to Kleenex or Thermos. Eventually, all US employees were laid off in January 2009, and today LiveJournal continues on as a site run by Russians, for Russians. (As Paolucci and Smith point out, however, an influx of users came to their fork Dreamwidth following SUP’s decision to move the site’s servers to Russia. Some of these users cited fears over the Russian government’s ability to subpoena digital data.)

Looking back, these former LiveJournal employees all agree that the service’s more insular nature was never going to be able to compete with the public-facing, data-aggregating might of Facebook and Twitter. Hassan recalls the day that Facebook introduced the concept of the “news feed,” which allowed users to see their friends’ updates in a more cohesive (but arguably voyeuristic) way. According to him, LiveJournal’s staff was planning to roll out a similar feature, but they feared the community backlash. “They took the heat for us, in a way, but it also changed the model of privacy in a way we didn’t expect,” he says. “These sites changed the world, but we didn’t try to adapt.”

Despite that, the LiveJournalers Ars spoke to look back at the platform as something more pure than the ubiquitous social media services of today, and it remains a professional experience that they won’t soon forget. “It really comes down to Twitter and Facebook wanting to be the Walmart of social media—everybody has one,” says Paolucci. “We wanted to be the mom-and-pop corner store of social media, but we sold to somebody who didn’t understand that. And that’s where Dreamwidth comes in.”

“We were the Linux of social media,” as Hassan puts it. “We never had the clear mental model of what the site was, but we had the features. We had the knobs and tuneables and features. Every feature that Facebook has rolled out since I left LJ, we had it first: post by photo, post by SMS, we had those a million years ago. You could call a phone number and record a message, and the audio would get posted to your journal. We had custom friend groups so you could manage where you wanted to post. We had basically all the major features you see today, like a friends page. But we didn’t quite figure out how to tell the story or keep people interested. We had every option, but nobody could get it to work. We had the robust privacy options that nobody understands how to use on Facebook. It was a less-public age of the Internet, and one that I sometimes wish we could go back to.”

Even though LiveJournal remains all but dead and gone to these ex-employees, its Russified corpse still continues to trudge along, animated by whatever die-hards continue to inhabit the community. Oh No They Didn’t still reports on the celebrity news of the day even now, though only a trickle of comments exist where there was once a flood.

But perhaps there’s no better microcosm for LiveJournal’s epic journey than the blog that belonged to the man behind Game of Thrones. Even though George R.R. Martin managed to hang out for a decade after the site’s initial downfall, nothing in particular seemed to trigger his 2018 move to a personal site. No fanfare accompanied it, just a brief message from one of the fantasist’s “minions.” Such is the nature of the erosion of our once-beloved digital spaces: there’s none of the collapsed majesty of a physical space like an abandoned castle, ivy threading its way through the crumbling latticework. Instead, LiveJournal moves forward as an aging pile of code, one day potentially rendered obsolete by something newer and better and remembered by those who lost countless hours to rigging it up in the first place.

Steven T. Wright is a writer, critic, and pedant based in the Twin Cities. He almost named a novel after a city in Final Fantasy, but his friends talked him out of it. His previous work on Ars includes “Life in (virtual) pit lane: The war stories of video game car design.”