As organizations grow complex, they’re managed through incorporeal abstractions that drift increasingly from the reality they represent.

On the smallest teams, decision-makers might be deep in the code on a daily basis. A bit larger, and you’re talking about tasks in sprints. More growth, and you’re talking about collections of tasks, and adopting fancy words like “epics.” At a hundred-plus engineers, you’re likely talking primarily in themes of work with focus on a couple key initiatives. At thousands, you might be talking about your investment framework for resourcing decisions.

No matter the path, metrics are your final destination.

Metrics are a remarkably effective abstraction.

A well-formed metric has enough context to understand how well you’re doing, contextualize that performance against historical performance, and define a clear, gradable goal.

An example metric with a goal might be:

20% of deploys were canaried in Q4, up from 10% in Q3, but missing our goal of 25%.

This is powerful for a couple of reasons. First, the historical context describes to the vector of our progress, especially when paired with a chart showing looking further back. Second, it’s very clear whether the goal has been hit, and the historical vector informs a general sense of how difficult the goal was. Finally, and most importantly, folks can do this assessment with minimal knowledge of the underlying topic.

The folks leading complex companies are quite capable of understanding the underlying work, but they can only afford to play this card sparingly. There are so many demands on their attention, and metrics become the great filter to prioritize which areas to observe from afar, and which to drill into.

It takes some time for an organization to gain the new competencies to fulfill this insatiable need for metrics. Good metrics require a deep understanding of the data underneath, and building that familiarity is real work. The beginning of the metrics-era is characterized by churn in metric selection. Each learning inspires a refinement across your catalog of metrics, and most new metrics requires new instrumentation, pipelines, and sanitation.

This takes time, and is difficult work, but it’s predictable work. You put in more time, learn more, and your metric selection becomes a durable, useful materialization of the reality underneath.

Well, that’s how it usually works, anyway. As I’ve gotten more experienced in defining and using metrics, more and more of my time is spent dealing with areas that defy easy measurement. Areas that I’ve at times been tempted to describe as unmeasurable.

When I meet new infrastructure leaders, one of my first questions is usually one of:

- “How do you measure security at your company?”

- “How do you measure productivity on your team?”

Answers vary, but generally the state of measurement for both leaves a lot to be desired. The challenges are fairly similar for both, so I’ll drill into measuring security in particular.

Measuring security

When we talk about measuring security, it’s pretty easy to identify output metrics that describe your desired outcomes. However, it’s often the case that either the numerator or denominator for security metrics is unknowable. For example, you might want to set a goal around detecting intrusions, but definitionally you can’t know what the denominator is, because that number includes undetected intrusions.

Similarly, in cases where you do know the numerator–e.g. the number of known security breaches–it’s generally the case that the only acceptable goal is zero. These forces work together to proliferate “zero metrics”, such as setting goals of “zero breaches”, “zero internal actor events”, “zero compromised systems”, and so on.

“Zero metrics” are a specialized form of binary metrics, where the only useful data is whether you’ve succeeded (hit zero) or failed (hit more than zero). These aren’t particularly useful, because they provide very coarse grading of performance, really just a pass/fail. Worse still, they aren’t actionable. Assuming it isn’t an area of neglect, you’d likely prioritize the same work next half if you had zero breaches as you would if you had four.

If we step back from these binary metrics, there are many extremely useful metrics worth considering to measure our security, such as:

- How quickly are libraries with CVEs upgraded?

- How old is your oldest active server?

- What percent of requests go over mTLS?

- How many folks have SSH access to servers?

- How many folks have root access to servers?

The challenge is that these are all input metrics which are excellent for measuring progress against a plan, but weak at measuring the plan’s quality. Sure, we encrypted 100% of servers’ storage, but to what extent has that contributed to our security?

The other issue with relying on input metrics is that they are too numerous and too specific to easily synthesize into useful understanding. This means they fail the critical role of providing senior leadership an abstraction through which to efficiently understand an area’s performance.

Synthetic metrics

Pulling these challenges together, we find a useful definition of what makes for a good metric of organizational performance:

- It should expose enough gradations to detect changes in performance over time,

- changes across gradations should guide useful action,

- they should be evaluable with limited context, and

- they should be sufficiently broad to abstract significant complexity.

At this point, I don’t think there is a natural security metric that has these properties, but fortunately we don’t have to rely on natural metrics. My approach lately has been creating synthetic metrics, which package input metrics into a useful abstraction.

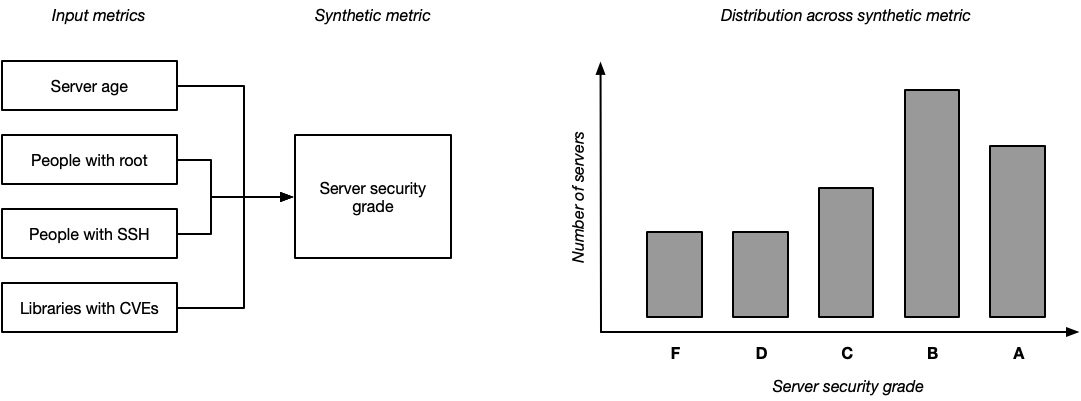

A good example of this is if you imagine creating a “server security grade”, where you assign every server a letter grade from “A” to “F” based on its input metrics. The particulars are a bit orthogonal here, but perhaps a server with an “A” security grade would be less than seven days old, running the latest operating system, and have very limited root access. Each day you’d assess a security grade to every server, and then you would be able to start tracking the distribution of servers across letter grades.

Rather than talking about each input metric in detail, instead you can start setting goals around shifting the distribution of grades. For example, your goaled metric might be:

80% of servers have a security grade of A, up from 60% in Q4, hitting our goal of 75%.

This replaces a great deal of complexity with something very concise. You can still have high leverage discussions around the definitions of each letter grade, but folks can get an understanding of the landscape without digging into those definitions. You can measure distribution shifts to evaluate long-term progress. If the distribution of grades shifts down, you can drill into which input metric caused that shift, and use that to identify corrective action.

Overall, I think this approach is surprisingly useful, but it’s not free. The main downside of this approach is the complexity in designing, instrumenting and evolving a synthetic metric. Depending on the tooling you’re using, the overhead of maintaining such metrics might be difficult to support, but I think as things get more complicated, it’s a powerful technique worth adding to your approach.

How else are folks creating metrics for the unmeasurable?

As an aside, measuring productivity is challenging for all the same reasons as measuring security. I’ve written a bit about this before, both summarizing Accelerate’s definition of productivity which focuses on using industry research to select the right input metrics, and in my introduction to systems thinking which tries to summarize input metrics into a comprehensible model.

My thinking has evolved here a bit, with a focus on internal developer surveys (but not CSAT scores, rather participation rate and the rate at which top concerns change) and a synthetic metric around workflow usability (which is based on a wide range of input metrics like build, test and deploy speed and reliability).

So much left to learn!