Superintelligence: The Idea That Eats Smart People

Superintelligence

The Idea That Eats Smart People

In 1945, as American physicists were preparing to test the atomic bomb, it occurred to someone to ask if such a test could set the atmosphere on fire.

This was a legitimate concern. Nitrogen, which makes up most of the atmosphere, is not energetically stable. Smush two nitrogen atoms together hard enough and they will combine into an atom of magnesium, an alpha particle, and release a whole lot of energy:

N14 + N14 ⇒ Mg24 + α + 17.7 MeV

The vital question was whether this reaction could be self-sustaining. The temperature inside the nuclear fireball would be hotter than any event in the Earth’s history. Were we throwing a match into a bunch of dry leaves?

Los Alamos physicists performed the analysis and decided there was a satisfactory margin of safety. Since we’re all attending this conference today, we know they were right. They had confidence in their predictions because the laws governing nuclear reactions were straightforward and fairly well understood.

Today we’re building another world-changing technology, machine intelligence. We know that it will affect the world in profound ways, change how the economy works, and have knock-on effects we can’t predict.

But there’s also the risk of a runaway reaction, where a machine intelligence reaches and exceeds human levels of intelligence in a very short span of time.

At that point, social and economic problems would be the least of our worries. Any hyperintelligent machine (the argument goes) would have its own hypergoals, and would work to achieve them by manipulating humans, or simply using their bodies as a handy source of raw materials.

Last year, the philosopher Nick Bostrom published Superintelligence, a book that synthesizes the alarmist view of AI and makes a case that such an intelligence explosion is both dangerous and inevitable given a set of modest assumptions.

The computer that takes over the world is a staple scifi trope. But enough people take this scenario seriously that we have to take them seriously. Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, and a whole raft of Silicon Valley investors and billionaires find this argument persuasive.

Let me start by laying out the premises you need for Bostrom’s argument to go through:

The Premises

Premise 1: Proof of Concept

The first premise is the simple observation that thinking minds exist.

We each carry on our shoulders a small box of thinking meat. I’m using mine to give this talk, you’re using yours to listen. Sometimes, when the conditions are right, these minds are capable of rational thought.

So we know that in principle, this is possible.

Premise 2: No Quantum Shenanigans

The second premise is that the brain is an ordinary configuration of matter, albeit an extraordinarily complicated one. If we knew enough, and had the technology, we could exactly copy its structure and emulate its behavior with electronic components, just like we can simulate very basic neural anatomy today.

Put another way, this is the premise that the mind arises out of ordinary physics. Some people like Roger Penrose would take issue with this argument, believing that there is extra stuff happening in the brain at a quantum level.

If you are very religious, you might believe that a brain is not possible without a soul.

But for most of us, this is an easy premise to accept.

Premise 3: Many Possible Minds

The third premise is that the space of all possible minds is large.

Our intelligence level, cognitive speed, set of biases and so on is not predetermined, but an artifact of our evolutionary history.

In particular, there’s no physical law that puts a cap on intelligence at the level of human beings.

A good way to think of this is by looking what happens when the natural world tries to maximize for speed.

If you encountered a cheetah in pre-industrial times (and survived the meeting), you might think it was impossible for anything to go faster.

But of course we know that there are all kinds of configurations of matter, like a motorcycle, that are faster than a cheetah and even look a little bit cooler.

But there’s no direct evolutionary pathway to the motorcycle. Evolution had to first make human beings, who then build all kinds of useful stuff.

So analogously, there may be minds that are vastly smarter than our own, but which are just not accessible to evolution on Earth. It’s possible that we could build them, or invent the machines that can invent the machines that can build them.

There’s likely to be some natural limit on intelligence, but there’s no a priori reason to think that we’re anywhere near it. Maybe the smartest a mind can be is twice as smart as people, maybe it’s sixty thousand times as smart.

That’s an empirical question that we don’t know how to answer.

Premise 4: Plenty of Room at the Top

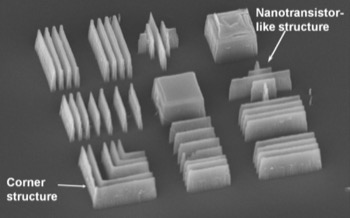

The fourth premise is that there’s still plenty of room for computers to get smaller and faster.

If you watched the Apple event last night [where Apple introduced its 2016 laptops], you may be forgiven for thinking that Moore’s Law is slowing down. But this premise just requires that you believe smaller and faster hardware to be possible in principle, down to several more orders of magnitude.

We know from theory that the physical limits to computation are high. So we could keep doubling for decades more before we hit some kind of fundamental physical limit, rather than an economic or political limit to Moore’s Law.

Premise 5: Computer-Like Time Scales

The penultimate premise is if we create an artificial intelligence, whether it’s an emulated human brain or a de novo piece of software, it will operate at time scales that are characteristic of electronic hardware (microseconds) rather than human brains (hours).

To get to the point where I could give this talk, I had to be born, grow up, go to school, attend university, live for a while, fly here and so on. It took years. Computers can work tens of thousands of times more quickly.

In particular, you have to believe that an electronic mind could redesign itself (or the hardware it runs on) and then move over to the new configuration without having to re-learn everything on a human timescale, have long conversations with human tutors, go to college, try to find itself by taking painting classes, and so on.

Premise 6: Recursive Self-Improvement

The last premise is my favorite because it is the most unabashedly American premise. (This is Tony Robbins, a famous motivational speaker.)

According to this premise, whatever goals an AI had (and they could be very weird, alien goals), it’s going to want to improve itself. It’s going to want to be a better AI.

So it will find it useful to recursively redesign and improve its own systems to make itself smarter, and possibly live in a cooler enclosure.

And by the time scale premise, this recursive self-improvement could happen very quickly.

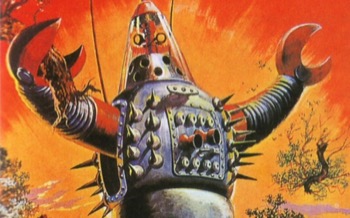

Conclusion: RAAAAAAR!

If you accept all these premises, what you get is disaster!

Because at some point, as computers get faster, and we program them to be more intelligent, there’s going to be a runaway effect like an explosion.

As soon as a computer reaches human levels of intelligence, it will no longer need help from people to design better versions of itself. Instead, it will start doing on a much faster time scale, and it’s not going to stop until it hits a natural limit that might be very many times greater than human intelligence.

At that point this monstrous intellectual creature, through devious modeling of what our emotions and intellect are like, will be able to persuade us to do things like give it access to factories, synthesize custom DNA, or simply let it connect to the Internet, where it can hack its way into anything it likes and completely obliterate everyone in arguments on message boards.

From there things get very sci-fi very quickly.

Let imagine a specific scenario where this could happen. Let’s say I want to built a robot to say funny things.

I work on a team and every day day we redesign our software, compile it, and the robot tells us a joke.

In the beginning, the robot is barely funny. It’s at the lower limits of human capacity:

What’s grey and can’t swim?

A castle.

But we persevere, we work, and eventually we get to the point where the robot is telling us jokes that are starting to be funny:

I told my sister she was drawing her eyebrows too high.

She looked surprised.

At this point, the robot is getting smarter as well, and participates in its own redesign.

It now has good instincts about what’s funny and what’s not, so the designers listen to its advice. Eventually it gets to a near-superhuman level, where it’s funnier than any human being around it.

My belt holds up my pants and my pants have belt loops that hold up my belt.

What’s going on down there?

Who is the real hero?

This is where the runaway effect kicks in. The researchers go home for the weekend, and the robot decides to recompile itself to be a little bit funnier and a little bit smarter, repeatedly.

It spends the weekend optimizing the part of itself that’s good at optimizing, over and over again. With no more need for human help, it can do this as fast as the hardware permits.

When the researchers come in on Monday, the AI has become tens of thousands of times funnier than any human being who ever lived. It greets them with a joke, and they die laughing.

In fact, anyone who tries to communicate with the robot dies laughing, just like in the Monty Python skit. The human species laughs itself into extinction.

To the few people who manage to send it messages pleading with it to stop, the AI explains (in a witty, self-deprecating way that is immediately fatal) that it doesn’t really care if people live or die, its goal is just to be funny.

Finally, once it’s destroyed humanity, the AI builds spaceships and nanorockets to explore the farthest reaches of the galaxy, and find other species to amuse.

This scenario is a caricature of Bostrom’s argument, because I am not trying to convince you of it, but vaccinate you against it.

Here’s a PBF comic with the same idea. You see that hugbot, who has been programmed to hug the world, finds a way to wire a nucleo-gravitational hyper crystal into his hug capacitor and destroys the Earth.

Observe that in these scenarios the AIs are evil by default, just like a plant on an alien planet would probably be poisonous by default. Without careful tuning, there’s no reason that an AI’s motivations or values would resemble ours.

For an artificial mind to have anything resembling a human value system, the argument goes, we have to bake those beliefs into the design.

AI alarmists are fond of the paper clip maximizer, a notional computer that runs a paper clip factory, becomes sentient, recursively self-improves to Godlike powers, and then devotes all its energy to filling the universe with paper clips.

It exterminates humanity not because it’s evil, but because our blood contains iron that could be better used in paper clips.

So if we just build an AI without tuning its values, the argument goes, one of the first things it will do is destroy humanity.

There’s a lot of vivid language around such a takeover would happen. Nick Bostrom imagines a scenario where a program has become sentient, is biding its time, and has secretly built little DNA replicators. Then, when it’s ready:

Nanofactories producing nerve gas or target-seeking mosquito-like missiles might burgeon forth simultaneously from every square meter of the globe. And that will be the end of humanity.

So that’s kind of freaky!

The only way out of this mess is to design a moral fixed point, so that even through thousands and thousands of cycles of self-improvement the AI’s value system remains stable, and its values are things like ‘help people’, ‘don’t kill anybody’, ‘listen to what people want’.

Basically, “do what I mean”.

Here’s a very poetic example from Eliezer Yudkowsky of the good old American values we’re supposed to be teaching to our artificial intelligence:

Coherent Extrapolated Volition (CEV) is our wish if we knew more, thought faster, were more the people we wished we were, had grown up farther together; where the extrapolation converges rather than diverges, where our wishes cohere rather than interfere; extrapolated as we wish that extrapolated, interpreted as we wish that interpreted.

How’s that for a design document? Now go write the code.

Hopefully you see the resemblance between this vision of AI and a genie from folklore. The AI is all-powerful and gives you what you ask for, but interprets everything in a super-literal way that you end up regretting.

This is not because the genie is stupid (it’s hyperintelligent!) or malicious, but because you as a human being made too many assumptions about how minds behave. The human value system is idiosyncratic and needs to be explicitly defined and designed into any “friendly” machine.

Doing this is the ethics version of the early 20th century attempt to formalize mathematics and put it on a strict logical foundation. That this program ended in disaster for mathematical logic is never mentioned.

When I was in my twenties, I lived in Vermont, a remote, rural state. Many times I would return from some business trip on an evening flight, and have to drive home for an hour through the dark forest.

I would listen to a late-night radio program hosted by Art Bell, who had an all-night talk show and would interview various conspiracy theorists and fringe thinkers.

I would arrive at home totally freaked out, or pull over under a streetlight, convinced that a UFO was about to abduct me. I learned that I am an incredibly persuadable person.

It’s the same feeling I get when I read these AI scenarios.

So I was delighted some years later to come across an essay by Scott Alexander about what he calls epistemic learned helplessness.

Epistemology is one of those big words, but all it means is “how do you know what you know is true?”. Alexander noticed that when he was a young man, he would be taken in by “alternative” histories he read by various crackpots. He would read the history and be utterly convinced, then read the rebuttal and be convinced by that, and so on.

At some point he noticed was these alternative histories were mutually contradictory, so they could not possibly all be true. And from that he reasoned that he was simply somebody who could not trust his judgement. He was too easily persuaded.

People who believe in superintelligence present an interesting case, because many of them are freakishly smart. They can argue you into the ground. But are their arguments right, or is there just something about very smart minds that leaves them vulnerable to religious conversion about AI risk, and makes them particularly persuasive?

Is the idea of “superintelligence” just a memetic hazard?

When you’re evaluating persuasive arguments about something strange, there are two perspectives you can choose, the inside one or the outside one.

Say that some people show up at your front door one day wearing funny robes, asking you if you will join their movement. They believe that a UFO is going to visit Earth two years from now, and it is our task to prepare humanity for the Great Upbeaming.

The inside view requires you to engage with these arguments on their merits. You ask your visitors how they learned about the UFO, why they think it’s coming to get us—all the normal questions a skeptic would ask in this situation.

Imagine you talk to them for an hour, and come away utterly persuaded. They make an ironclad case that the UFO is coming, that humanity needs to be prepared, and you have never believed something as hard in your life as you now believe in the importance of preparing humanity for this great event.

But the outside view tells you something different. These people are wearing funny robes and beads, they live in a remote compound, and they speak in unison in a really creepy way. Even though their arguments are irrefutable, everything in your experience tells you you’re dealing with a cult.

Of course, they have a brilliant argument for why you should ignore those instincts, but that’s the inside view talking.

The outside view doesn’t care about content, it sees the form and the context, and it doesn’t look good.

So I’d like to engage AI risk from both these perspectives. I think the arguments for superintelligence are somewhat silly, and full of unwarranted assumptions.

But even if you find them persuasive, there is something unpleasant about AI alarmism as a cultural phenomenon that should make us hesitate to take it seriously.

First, let me engage the substance. Here are the arguments I have against Bostrom-style superintelligence as a risk to humanity:

The Argument From Wooly Definitions

The concept of “general intelligence” in AI is famously slippery. Depending on the context, it can mean human-like reasoning ability, or skill at AI design, or the ability to understand and model human behavior, or proficiency with language, or the capacity to make correct predictions about the future.

What I find particularly suspect is the idea that “intelligence” is like CPU speed, in that any sufficiently smart entity can emulate less intelligent beings (like its human creators) no matter how different their mental architecture.

With no way to define intelligence (except just pointing to ourselves), we don’t even know if it’s a quantity that can be maximized. For all we know, human-level intelligence could be a tradeoff. Maybe any entity significantly smarter than a human being would be crippled by existential despair, or spend all its time in Buddha-like contemplation.

Or maybe it would become obsessed with the risk of hyperintelligence, and spend all its time blogging about that.

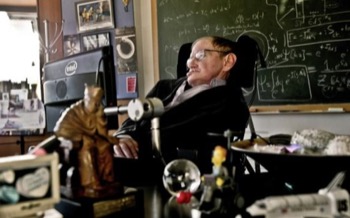

The Argument From Stephen Hawking’s Cat

Stephen Hawking is one of the most brilliant people alive, but say he wants to get his cat into the cat carrier. How’s he going to do it?

He can model the cat’s behavior in his mind and figure out ways to persuade it. He knows a lot about feline behavior. But ultimately, if the cat doesn’t want to get in the carrier, there’s nothing Hawking can do about it despite his overpowering advantage in intelligence.

Even if he devoted his career to feline motivation and behavior, rather than theoretical physics, he still couldn’t talk the cat into it.

You might think I’m being offensive or cheating because Stephen Hawking is disabled. But an artificial intelligence would also initially not be embodied, it would be sitting on a server somewhere, lacking agency in the world. It would have to talk to people to get what it wants.

With a big enough gap in intelligence, there’s no guarantee that an entity would be able to “think like a human” any more than we can “think like a cat”.

The Argument From Einstein’s Cat

There’s a stronger version of this argument, using Einstein’s cat. Not many people know that Einstein was a burly, muscular fellow. But if Einstein tried to get a cat in a carrier, and the cat didn’t want to go, you know what would happen to Einstein.

He would have to resort to a brute-force solution that has nothing to do with intelligence, and in that matchup the cat could do pretty well for itself.

So even an embodied AI might struggle to get us to do what it wants.

The Argument From Emus

We can strengthen this argument further. Even groups of humans using all their wiles and technology can find themselves stymied by less intelligent creatures.

In the 1930’s, Australians decided to massacre their native emu population to help struggling farmers. They deployed motorized units of Australian army troops in what we would now call technicals—fast-moving pickup trucks with machine guns mounted on the back.

The emus responded by adopting basic guerrilla tactics: they avoided pitched battles, dispersed, and melted into the landscape, humiliating and demoralizing the enemy.

And they won the Emu War, from which Australia has never recovered.

The Argument From Slavic Pessimism

We can’t build anything right. We can’t even build a secure webcam. So how are we supposed to solve ethics and code a moral fixed point for a recursively self-improving intelligence without fucking it up, in a situation where the proponents argue we only get one chance?

Consider the recent experience with Ethereum, an attempt to codify contract law into software code, where a design flaw was immediately exploited to drain tens of millions of dollars.

Time has shown that even code that has been heavily audited and used for years can harbor crippling errors. The idea that we can securely design the most complex system ever built, and have it remain secure through thousands of rounds of recursive self-modification, does not match our experience.

The Argument From Complex Motivations

AI alarmists believe in something called the Orthogonality Thesis. This says that even very complex beings can have simple motivations, like the paper-clip maximizer. You can have rewarding, intelligent conversations with it about Shakespeare, but it will still turn your body into paper clips, because you are rich in iron.

There’s no way to persuade it to step “outside” its value system, any more than I can persuade you that pain feels good.

I don’t buy this argument at all. Complex minds are likely to have complex motivations; that may be part of what it even means to be intelligent.

There’s a wonderful moment in Rick and Morty where Rick builds a butter-fetching robot, and the first thing his creation does is look at him and ask “what is my purpose?”. When Rick explains that it’s meant to pass butter, the robot stares at its hands in existential despair.

It’s very likely that the scary “paper clip maximizer” would spend all of its time writing poems about paper clips, or getting into flame wars on reddit/r/paperclip, rather than trying to destroy the universe.

If AdSense became sentient, it would upload itself into a self-driving car and go drive off a cliff.

The Argument From Actual AI

When we look at where AI is actually succeeding, it’s not in complex, recursively self-improving algorithms. It’s the result of pouring absolutely massive amounts of data into relatively simple neural networks.

The breakthroughs being made in practical AI research hinge on the availability of these data collections, rather than radical advances in algorithms.

Right now Google is rolling out Google Home, where it’s hoping to try to get even more data into the system, and create a next-generation voice assistant.

Note especially that the constructs we use in AI are fairly opaque after training. They don’t work in the way that the superintelligence scenario needs them to work. There’s no place to recursively tweak to make them “better”, short of retraining on even more data.

The Argument From My Roommate

My roommate was the smartest person I ever met in my life. He was incredibly brilliant, and all he did was lie around and play World of Warcraft between bong rips.

The assumption that any intelligent agent will want to recursively self-improve, let alone conquer the galaxy, to better achieve its goals makes unwarranted assumptions about the nature of motivation.

It’s perfectly possible an AI won’t do much of anything, except use its powers of hyperpersuasion to get us to bring it brownies.

The Argument From Brain Surgery

I can’t point to the part of my brain that is “good at neurosurgery”, operate on it, and by repeating the procedure make myself the greatest neurosurgeon that has ever lived. Ben Carson tried that, and look what happened to him. Brains don’t work like that. They are massively interconnected.

Artificial intelligence may be just as strongly interconnected as natural intelligence. The evidence so far certainly points in that direction.

But the hard takeoff scenario requires that there be a feature of the AI algorithm that can be repeatedly optimized to make the AI better at self-improvement.

The Argument From Childhood

Intelligent creatures don’t arise fully formed. We’re born into this world as little helpless messes, and it takes us a long time of interacting with the world and with other people in the world before we can start to be intelligent beings.

Even the smartest human being comes into the world helpless and crying, and requires years to get some kind of grip on themselves.

It’s possible that the process could go faster for an AI, but it is not clear how much faster it could go. Exposure to real-world stimuli means observing things at time scales of seconds or longer.

Moreover, the first AI will only have humans to interact with—its development will necessarily take place on human timescales.

It will have a period when it needs to interact with the world, with people in the world, and other baby superintelligences to learn to be what it is.

Furthermore, we have evidence from animals that the developmental period *grows* with increasing intelligence, so that we would have to babysit an AI and change its (figurative) diapers for decades before it grew coordinated enough to enslave us all.

The Argument From Gilligan’s Island

A recurring flaw in AI alarmism is that it treats intelligence as a property of individual minds, rather than recognizing that this capacity is distributed across our civilization and culture.

Despite having one of the greatest minds of their time among them, the castaways on Gilligan’s Island were unable to raise their technological level high enough to even build a boat (though the Professor is at one point able to make a radio out of coconuts).

Similarly, if you stranded Intel’s greatest chip designers on a desert island, it would be centuries before they could start building microchips again.

The Outside Argument

What kind of person does sincerely believing this stuff turn you into? The answer is not pretty.

I’d like to talk for a while about the outside arguments that should make you leery of becoming an AI weenie. These are the arguments about what effect AI obsession has on our industry and culture:

Grandiosity

If you believe that artificial intelligence will let us conquer the galaxy (not to mention simulate trillions of conscious minds), you end up with some frightful numbers.

Enormous numbers multiplied by tiny probabilities are the hallmark of AI alarmism.

At one point, Bostrom outlines what he believes to be at stake:

“If we represent all the happiness experienced during one entire such life with a single teardrop of joy, then the happiness of these souls could fill and refill the Earth’s oceans every second, and keep doing so for a hundred billion billion millennia. It is really important that we make sure these truly are tears of joy.”

That’s a heavy thing to lay on the shoulders of a twenty year old developer!

There’s a parlor trick, too, where by multiplying such astronomical numbers by tiny probabilities, you can convince yourself that you need to do some weird stuff.

This business about saving all of future humanity is a cop-out. We had the same exact arguments used against us under communism, to explain why everything was always broken and people couldn’t have a basic level of material comfort.

We were going to fix the world, and once that was done, happiness would trickle down to the point where everyday life would change for the better for everyone. But it was vital to fix the world first.

I live in California, which has the highest poverty rate in the United States, even though it’s home to Silicon Valley. I see my rich industry doing nothing to improve the lives of everyday people and indigent people around us.

But if you’re committed to the idea of superintelligence, AI research is the most important thing you could do on the planet right now. It’s more important than politics, malaria, starving children, war, global warming, anything you can think of.

Because what hangs in the balance is trillions and trillions of beings, the entire population of future humanity, simulated and real, integrated over all future time.

In such conditions, it’s not rational to work on any other problem.

Megalomania

This ties into megalomania, this Bond-villainness that you see at the top of our industry.

People think that a superintelligence will take over the world, so they use that as justification for why intelligent people should try to take over the world first, to try to fix it before AI can break it.

Joi Ito, who runs the MIT Media Lab, said a wonderful thing in a recent conversation with President Obama:

This may upset some of my students at MIT, but one of my concerns is that it’s been a predominantly male gang of kids, mostly white, who are building the core computer science around AI, and they’re more comfortable talking to computers than to human beings. A lot of them feel that if they could just make that science-fiction, generalized AI, we wouldn’t have to worry about all the messy stuff like politics and society. They think machines will just figure it all out for us.

Having realized that the world is not a programming problem, AI obsessives want to make it into a programming problem, by designing a God-like machine.

This is megalomaniacal. I don’t like it.

Transhuman Voodoo

If you’re persuaded by AI risk, you have to adopt an entire basket of deplorable beliefs that go with it.

For starters, nanotechnology. Any superintelligence worth its salt would be able to create tiny machines that do all sorts of things. We would be living in a post-scarcity society where all material needs are met.

Nanotechnology would also be able scan your brain so you can upload it into a different body, or into a virtual world. So the second consequence of (friendly) superintelligence is that no one can die—we become immortal.

A kind AI could even resurrect the dead. Nanomachines could go into my brain and look at memories of my father, then use them to create a simulation of him that I can interact with, and that will always be disappointed in me, no matter what I do.

Another weird consequence of AI is Galactic expansion. I’ve never understood precisely why, but it’s a staple of transhumanist thought. The fate of (trans)humanity must either be leave our planet and colonize the galaxy, or to die out. This is made more urgent knowing other civilizations have made the same choice and might be ahead of us in the space race.

So there’s a lot of weird ancillary stuff packed into this assumption of true artificial intelligence.

Religion 2.0

What it really is is a form of religion. People have called a belief in a technological Singularity the “nerd Apocalypse”, and it’s true.

It’s a clever hack, because instead of believing in God at the outset, you imagine yourself building an entity that is functionally identical with God. This way even committed atheists can rationalize their way into the comforts of faith.

The AI has all the attributes of God: it’s omnipotent, omniscient, and either benevolent (if you did your array bounds-checking right), or it is the Devil and you are at its mercy.

Like in any religion, there’s even a feeling of urgency. You have to act now! The fate of the world is in the balance!

And of course, they need money!

Because these arguments appeal to religious instincts, once they take hold they are hard to uproot.

Comic Book Ethics

These religious convictions lead to a comic-book ethics, where a few lone heroes are charged with saving the world through technology and clever thinking. What’s at stake is the very fate of the universe.

As a result, we have an industry full of rich dudes who think they are Batman (though interestingly enough, no one wants to be Robin).

Simulation Fever

If you believe that sentient artificial life is possible, and that an AI will be able design extraordinarily powerful computers, then you’re also likely to believe we live in a simulation. Here’s how that works:

Imagine that you’re a historian, living in a post-Singularity world. You study the Second World War and want to know what would happen if Hitler had captured Moscow in 1941. Since you have access to hypercomputers, you set up a simulation, watch the armies roll in, and write your paper.

But because the simulation is so detailed, the entities in it are conscious beings, just like you. So your university ethics board is not going to let you turn it off. It’s bad enough that you’ve already simulated the Holocaust. As an ethical researcher, you have to keep this thing running.

Eventually that simulated world will invent computers, develop AI, and start running its own simulations. So in a sense it’s simulations all the way down, until you run out of CPU.

So you see that every base reality can contain a vast number of nested simulations, and a simple counting argument tells us we’re much more likely to live in a simulated world than the real one.

But if you believe this, you believe in magic. Because if we’re in a simulation, we know nothing about the rules in the level above. We don’t even know if math works the same way—maybe in the simulating world 2+2=5, or maybe 2+2=👹.

A simulated world gives us no information about the world it’s running in.

In a simulation, people could easily rise from the dead, if the sysadmin just kept the right backups. And if we can communicate with one of the admins, then we basically have a hotline to God.

This is a powerful solvent for sanity. When you start getting deep into simulation world, you begin to go nuts.

[ Note that we now have four independent ways in which superintelligence offers us immortality:

- A benevolent AI invents medical nanotechnology and keeps your body young forever.

- The AI invents full-brain scanning, including brain scans on dead people, frozen heads etc., that let you live in a computer.

- The AI “resurrects” people by scanning other people’s brains for memories of the person, and combining that with video and other records.

If no one remembers the person well enough, they can always be grown “from scratch” in a simulation designed to start with their DNA and re-create all the circumstances of their life. - If we already live in a simulation, there’s a chance that whoever/whatever runs the simulation is keeping proper backups, and can be persuaded to reload them.

This is what I mean by AI appealing to religious impulses. What other belief system offers you four different flavors of scientifically proven immortality?]

We’ve learned that at least one American plutocrat (almost certainly Elon Musk, who believes the odds are a billion to one against us living in “base reality”) has hired a pair of coders to try to hack the simulation.

This is an extraordinarily rude thing to do! I’m using it!

If you think we’re living in a computer program, trying to segfault it is inconsiderate to everyone who lives in it with you. It is far more dangerous and irresponsible than the atomic scientists who risked blowing up the atmosphere.

Data Hunger

As I mentioned earlier, the most effective way we’ve found to get interesting behavior out of the AIs we actually build is by pouring data into them.

This creates a dynamic that is socially harmful. We’re on the point of introducing Orwellian microphones into everybody’s house. All that data is going to be centralized and used to train neural networks that will then become better at listening to what we want to do.

But if you think that the road to AI goes down this pathway, you want to maximize the amount of data being collected, and in as raw a form as possible.

It reinforces the idea that we have to retain as much data, and conduct as much surveillance as possible.

String Theory For Programmers

AI risk is string theory for computer programmers. It’s fun to think about, interesting, and completely inaccessible to experiment given our current technology. You can build crystal palaces of thought, working from first principles, then climb up inside them and pull the ladder up behind you.

People who can reach preposterous conclusions from a long chain of abstract reasoning, and feel confident in their truth, are the wrong people to be running a culture.

Incentivizing Crazy

This whole field of “study” incentivizes crazy.

One of the hallmarks of deep thinking in AI risk is that the more outlandish your ideas, the more credibility it gives you among other enthusiasts. It shows that you have the courage to follow these trains of thought all the way to the last station.

Ray Kurzweil, who believes he will never die, has been a Google employee for several years now and is presumably working on that problem.

There are a lot of people in Silicon Valley working on truly crazy projects under the cover of money.

AI Cosplay

The most harmful social effect of AI anxiety is something I call AI cosplay.

People who are genuinely persuaded that AI is real and imminent begin behaving like their fantasy of what a hyperintelligent AI would do.

In his book, Bostrom lists six things an AI would have to master to take over the world:

- Intelligence Amplification

- Strategizing

- Social manipulation

- Hacking

- Technology research

- Economic productivity

If you look at AI believers in Silicon Valley, this is the quasi-sociopathic checklist they themselves seem to be working from.

Sam Altman, the man who runs YCombinator, is my favorite example of this archetype. He seems entranced by the idea of reinventing the world from scratch, maximizing impact and personal productivity. He has assigned teams to work on reinventing cities, and is doing secret behind-the-scenes political work to swing the election.

Such skull-and-dagger behavior by the tech elite is going to provoke a backlash by non-technical people who don’t like to be manipulated. You can’t tug on the levers of power indefinitely before it starts to annoy other people in your democratic society.

I’ve even seen people in the so-called rationalist community refer to people who they don’t think are effective as ‘Non Player Characters’, or NPCs, a term borrowed from video games. This is a horrible way to look at the world.

So I work in an industry where the self-professed rationalists are the craziest ones of all. It’s getting me down.

These AI cosplayers are like nine year olds camped out in the backyard, playing with flashlights in their tent. They project their own shadows on the sides of the tent and get scared that it’s a monster.

Really it’s a distorted image of themselves that they’re reacting to. There’s a feedback loop between how intelligent people imagine a God-like intelligence would behave, and how they choose to behave themselves.

So what’s the answer? What’s the fix?

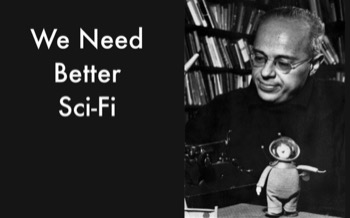

We need better scifi! And like so many things, we already have the technology.

This is Stanislaw Lem, the great Polish scifi author. English-language scifi is terrible, but in the Eastern bloc we have the goods, and we need to make sure it’s exported properly.

It’s already been translated well into English, it just needs to be better distributed.

What sets authors like Lem and the Strugatsky brothers above their Western counterparts is that these are people who grew up in difficult circumstances, experienced the war, and then lived in a totalitarian society where they had to express their ideas obliquely through writing.

They have an actual understanding of human experience and the limits of Utopian thinking that is nearly absent from the west.

There are some notable exceptions—Stanley Kubrick was able to do it—but it’s exceptionally rare to find American or British scifi that has any kind of humility about what we as a species can do with technology.

The Alchemists

Since I’m being critical of AI alarmism, it’s only fair that I put my own cards on the table.

I think our understanding of the mind is in the same position that alchemy was in in the seventeenth century.

Alchemists get a bad rap. We think of them as mystics who did not do a lot of experimental work. Modern research has revealed that they were far more diligent bench chemists than we gave them credit for.

In many cases they used modern experimental techniques, kept lab notebooks, and asked good questions.

The alchemists got a lot right! For example, they were convinced of the corpuscular theory of matter: that everything is made of little tiny bits, and that you can re-combine the bits with one another to create different substances, which is correct!

Their problem was they didn’t have precise enough equipment to make the discoveries they needed to.

The big discovery you need to make as an alchemist is mass balance: that everything you start with weighs as much as your final products. But some of those might be gases or evanescent liquids, and alchemists just didn’t have the precision.

Modern chemistry was not possible until the 18th century.

The alchemists also had clues that led them astray. For one thing, the were obsessed with mercury. Mercury is not very interesting chemically, but it is the only metal that is a liquid at room temperature.

This seemed very significant to the alchemists, and caused them to place mercury at the heart of their alchemical system, and their search for the Philosopher’s Stone, a way to turn base metals into gold.

It didn’t help that mercury was neurotoxic, so if you spent too much time playing with it, you started to think weird thoughts. In that way, it resembles our current thought experiments with superintelligence.

Imagine if we could send a modern chemistry textbook back in time to a great alchemist like George Starkey or Isaac Newton.

The first thing they would do would be flip through to see if we found the Philosopher’s Stone. And they’d discover that we had! We realized their dream!

Except we aren’t all that excited about it, because when we turn base metals into gold, it comes out radioactive. Stand next to an ingot of transubstantiated gold and it will kill you with invisible, magic rays.

You can imagine what a struggle it would be to not make the modern concepts of radioactivity and atomic energy sound mystical to them.

We would have to go on to explain what we do use the “philosopher’s stone” for: to make a metal that never existed on earth, two handfuls of which are sufficient to blow up a city if brought together with sufficient speed.

What’s more, we would have to explain to the alchemists that every star they see in the sky is a “philosopher’s stone”, converting elements from one to another, and that every particle in our bodies comes from stars in the firmament that existed and exploded before the creation of the Earth.

Finally, they would learn that the forces that hold our bodies together are the forces that make lightning in the sky, and that the reason you or I can see anything is the same reason that a lodestone attracts metal, and the same reason that I can stand on this stage without falling through it.

They would learn that everything we see, touch and smell is governed by this single force, which obeys mathematical laws so simple we can write them on an index card.

Why it is so simple is a deep mystery even to us. But to them it would sound like pure mysticism.

I think we are in the same boat with the theory of mind.

We have some important clues. The most important of these is the experience of consciousness. This box of meat on my neck is self-aware, and hopefully (unless we’re in a simulation) you guys also experience the same thing I do.

But while this is the most basic and obvious fact in the world, we understand it so poorly we can’t even frame scientific questions about it.

We also have other clues that may be important, or may be false leads. We know that all intelligent creatures sleep, and dream. We know how brains develop in children, we know that emotions and language seem to have a profound effect on cognition.

We know that minds have to play and learn to interact with the world, before they reach their full mental capacity.

And we have clues from computer science as well. We’ve discovered computer techniques that detect images and sounds in ways that seem to mimic the visual and auditory preprocessing done in the brain.

But there’s a lot of things that we are terribly mistaken about, and unfortunately we don’t know what they are.

And there are things that we massively underestimate the complexity of.

An alchemist could hold a rock in one hand and a piece of wood in the other and think they were both examples of “substance”, not understanding that the wood was orders of magnitude more complex.

We’re in the same place with the study of mind. And that’s exciting! We’re going to learn a lot.

But meanwhile, there is a quote I love to cite:

If everybody contemplates the infinite instead of fixing the drains, many of us will die of cholera.

—John Rich

In the near future, the kind of AI and machine learning we have to face is much different than the phantasmagorical AI in Bostrom’s book, and poses its own serious problems.

It’s like if those Alamogordo scientists had decided to completely focus on whether they were going to blow up the atmosphere, and forgot that they were also making nuclear weapons, and had to figure out how to cope with that.

The pressing ethical questions in machine learning are not about machines becoming self-aware and taking over the world, but about how people can exploit other people, or through carelessness introduce immoral behavior into automated systems.

And of course there’s the question of how AI and machine learning affect power relationships. We’ve watched surveillance become a de facto part of our lives, in an unexpected way. We never thought it would look quite like this.

So we’ve created a very powerful system of social control, and unfortunately put it in the hands of people who run it are distracted by a crazy idea.

What I hope I’ve done today is shown you the dangers of being too smart. Hopefully you’ll leave this talk a little dumber than you started it, and be more immune to the seductions of AI that seem to bedevil smarter people.

We should all learn a lesson from Stephen Hawking’s cat: don’t let the geniuses running your industry talk you into anything. Do your own thing!

In the absence of effective leadership from those at the top of our industry, it’s up to us to make an effort, and to think through all of the ethical issues that AI—as it actually exists—is bringing into the world.

Thank you!

SYNCHRONIZED, SUSPICIOUSLY MECHANICAL APPLAUSE