Introduction

The purpose of this article is to document the process I often use to plan and execute off-trail trips in the mountains using digital mapping and navigation tools. My overall goal is to provide the reader with part of a framework that can be used for planning mountainous, off-trail routes that are achievable by hikers without mountaineering experience in a safe and efficient manner.

Route Planning Objectives

The decision to visit a particular region for a backpacking trip may include one of the following:

- It is close to home and does not require a lot of travel.

- It is far from home, so it feels exotic.

- “I saw others hiking here on Instagram, and it looks like a neat place.”

- My family is visiting the in-laws and this nearby wilderness area will be a nice place to decompress.

However, once you have settled upon the overall region, it is time to plan the actual route. This process is more nuanced and complex, so now that you are away from the in-laws, you will have to drill down to determine more specific objectives.

Objective #1: Achievement of a Progress Goal

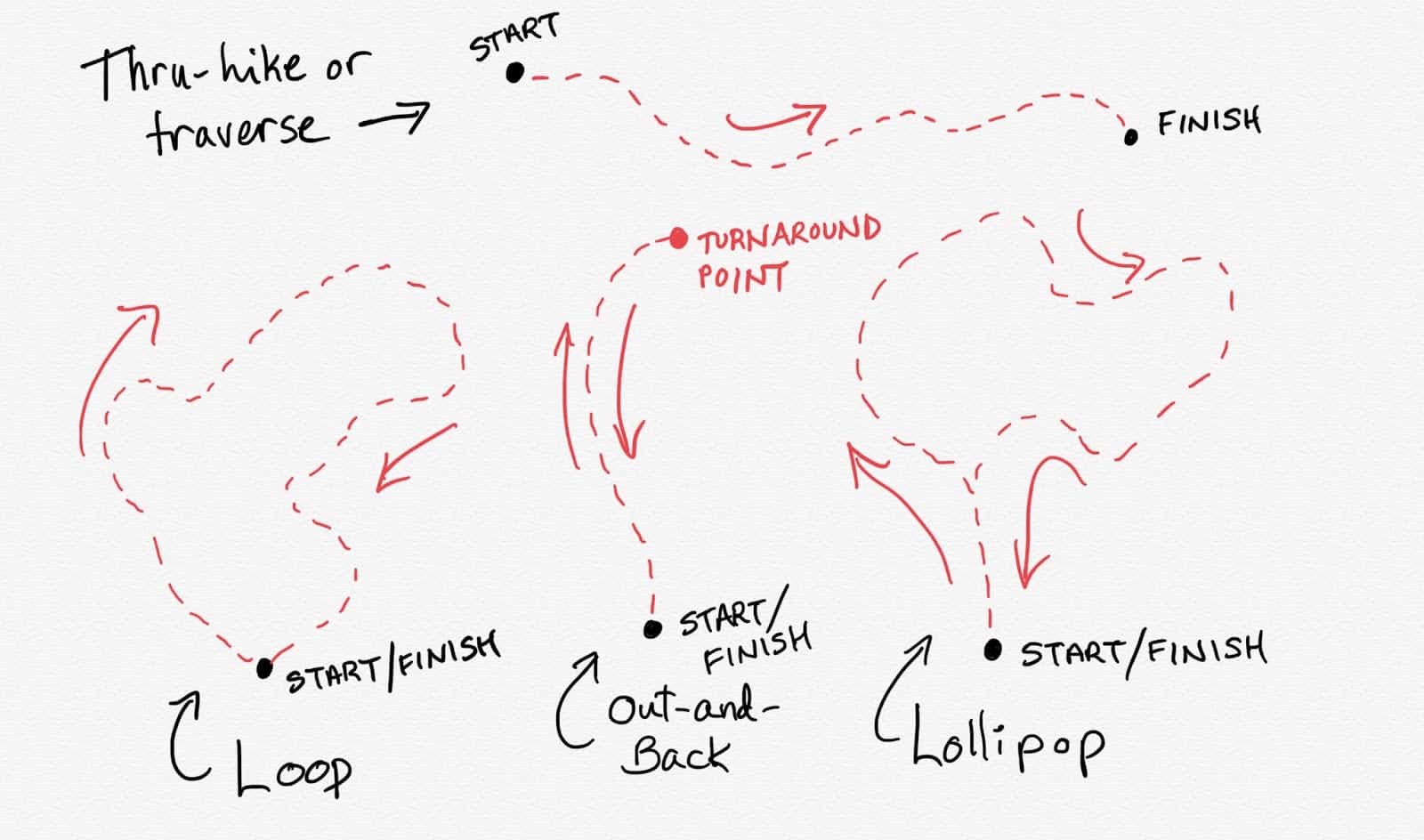

The most common way to plan a route is to plan a path from point A to point B (a traverse or thru-hike) or a path that starts and ends at the same location (a loop). Out-and-back and lollipop routes are common as well.

Objective #2: Visit Specific Places

Part of your route planning process may include the need to visit a specific place as an objective, and this preliminary need may then dictate the start and/or end point of a trip. Fishermen may be seeking trophy trout at a particular lake, climbers may be tackling a particular route on a peak, and photographers may be wanting to capture an image of a particular scene.

If you have a tolerance for a little bit of suffering, along with route planning and navigation skills, you can reach locations like this that are far off-trail. Lakes like this one hold treasures for the intrepid.

Objective #3: Maximize Aesthetics

A route may take on the aesthetic preferences of the hiker. For example, in the case where two routes traverse the same mountain range between points A and B, aesthetic values may come into play when making a decision. Aesthetics may include things like the comfort afforded by camping locations or scenic beauty.

Many of my mountain routes spend a lot of time above the treeline. Camping in a location with expansive views is one of the greatest rewards of mountain travel.

Objective #4: Maximize Efficiency

Planning an efficient route is a numbers game and an exercise that appeals more to left-brained hikers. An efficient route might be one that minimizes the mileage, elevation gain/loss, or travel time between points A and B. Maximizing efficiency requires an acute understanding of terrain and topography.

One of the routes I’ve taken in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness a number of times travels in a nearly-perfect straight line for more than 15 miles – all off-trail, and all above the treeline. We affectionately refer to it by its compass direction: “Hey, let’s take the 285 over to Zimmer Creek!” The route travels along a natural fault line, with only minor ups and downs along the way.

Objective #5: Minimize Risk

When planning a route that is designed to minimize risk, environmental and other objective hazards must be considered. Terrain steepness and difficulty, exposure to inclement weather while hiking and camping, river crossings, and snow conditions are a few things that must be considered when assessing the risk of a particular route.

Negotiating a flooded canyon in Utah (Lake Powell area). In this instance, understanding how the highly variable reservoir levels influence your ability to travel through a canyon can have a dramatic impact on whether or not a route here is passable.

These are the five objectives I usually consider when planning a route. You may have a different list!

Route Planning Resources

In the old days, I planned my routes at a kitchen table with USGS quadrangle maps and a pot of coffee. Sometimes, depending on the area I was visiting, I’d read hiking or climbing guidebooks for additional beta. Now, between the internet and digital imagery, we have access to a large body of information that we can tap into for route planning resources.

Viewing 3D satellite imagery during the “route discovery” process of the 2018 Whitetail Trek, as part of Backpacking Light’s Wilderness Adventures Program.

Trip Report Websites

Trip report websites provide some of the best sources of beta for obscure routes.

The ones I use most often include the Backpackinglight.com Forums and Summit Post. My gateway into these websites is most often a Google search for specific place names (lakes, peaks, trails, etc.).

Youtube

Youtube is becoming an increasingly valuable resource as well, as video production becomes easier and cheaper for the masses.

I’ve discovered some value out of trip report videos posted by others. Sometimes, it’s nice to see video examples of surrounding terrain and camping areas, or to see water conditions in backcountry whitewater canyons when planning a packrafting trek.

Google Image Search

A Google Image search can be valuable for evaluating the scenic beauty of various places, or for collecting beta on off-trail routes by examining high-resolution photos taken by others.

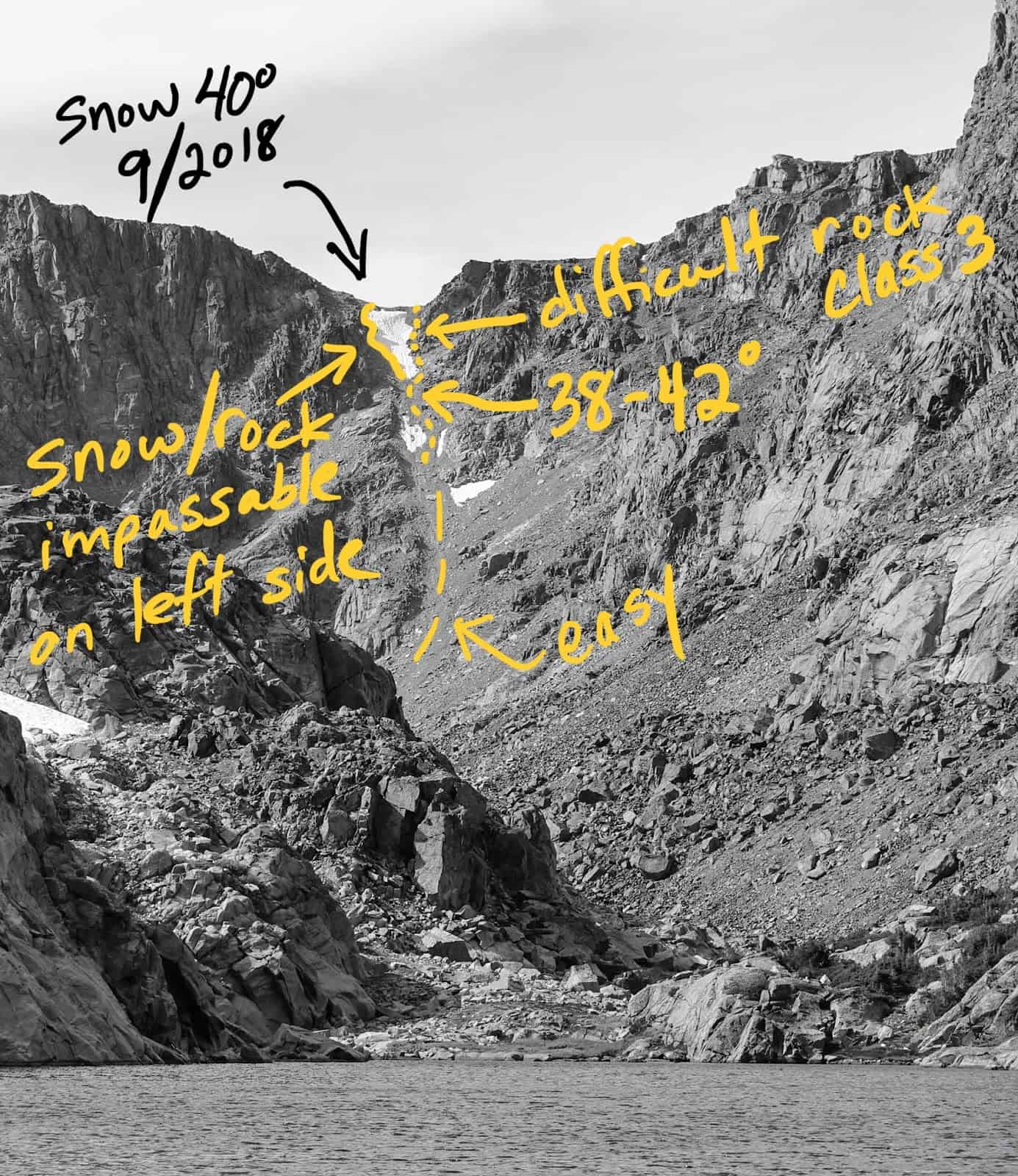

I use Google image search primarily to see what the routes over obscure mountain passes might look like, by searching for images of peak and/or lake basin names.

This image provided the beta I could use to reconcile with my notes about previous climbs of this pass.

Guidebooks

Hiking guidebooks such as those offered by Falcon Press provide valuable information for beginning and intermediate hikers looking for interesting trails that others have done.

Long distance trail guidebooks and databooks are considered all but essential for those planning thru-hikes, and provide additional information about resupply and other logistics (e.g., lodging, dining, transportation). A wealth of information is available for popular long distance trails like the Appalachian Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail.

Climbing guidebooks offer beta for off-trail travel that can be invaluable for more experienced hikers wanting to plan more creative routes. Some of my favorites include The High Sierra, Washington Scrambles, The Beckey Guides for the Cascades, and Select Peaks of Greater Yellowstone.

Fishing guidebooks aren’t just for fishermen. They often contain descriptions of obscure off-trail routes to lakes and streams found in remote wilderness areas. Marcuson’s fishing guide has given me more meaningful beta about hiking in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness than virtually any other resource. Reading the published fishing journals from old-timers like Finis Mitchell not only reveal valuable route information, but also add immensely to your understanding of the pioneers that trekked before you.

Some trusted sources.

Maps

Topo maps remain the de facto standard for both backcountry route planning and real-time navigation. Paper maps offer the advantage of being able to see larger areas at once. Spreading paper maps across a large table is a useful practice for planning longer routes.

Planning a trip across the entire Bob Marshall Wilderness requires a lot of big maps – here, tabletop mapping with paper maps is best for looking at big picture routes across vast landscapes.

USGS quadrangle maps (1:24,000 scale) provide the best detail for planning off-trail routes, but you shouldn’t rely on their outdated trail locations and property boundaries. Digital (e.g., web-based) maps like Caltopo or Hillmap offer the advantages of access to entire world-wide topographic map sets, additional layers (e.g., route shading, slope angles, satellite imagery), and route-making (and route analysis, e.g., mileage, elevation gain/loss) using integrated path and waypoint tools.

Trail maps that are up-to-date and based on the latest GIS data are valuable for identifying the exact location and status of maintained trails. My favorite trail maps are 1:100k maps from Beartooth Publishing and Trails Illustrated – they are waterproof, lightweight and compact, cover large areas, double-sided, and durable. Just as you shouldn’t rely on 1:24k USGS quads for trail navigating, you shouldn’t rely on 1:100k trail maps for complex off-trail travel.

Satellite Imagery

Satellite imagery can provide information about terrain and ground cover that can’t be gleaned from other sources. I use satellite imagery layers in Caltopo to look at rivers (for both packrafting and points of crossing), to identify wildfire burn areas (not my favorite places for off-trail travel!), to identify potential camping locations, and to identify cliffy terrain for alpine routes.

Google Earth is the best tool I’ve found for identifying extremely steep terrain that may pose problems for non-technical trekking. It’s based on satellite imagery, but perspective can be changed to a profile view that gives a much better feel for steepness. In addition, being able to “fly over” a route and visualize it before you attempt it is very exciting!

Member’s Only Content

Login as a Premium or Unlimited Member to read the comprehensive Performance Assessment and Author Commentary sections of this review:

- The Route Planning Process (A Case Study)

- How Route Planning Works: Linear, Chaotic, and Mesh Network Models

- Case Study: Princess Lake to Froze-to-Death Lake via the Froze-to-Death Plateau

- Overview – How to Address the Five Objectives

- Resources and Processes

- Topo Mapping

- Route Discovery Using Slope Angle Analysis

- Evaluating Route Hazards Using Satellite Imagery

- Case Study in Slope Angle Analysis: Explorer Pass in Utah’s Uinta Range

- Applying the Case Study to the Froze-to-Death Plateau Traverse

- Assessing Route Difficulty – Distance and Elevation Profiles

- Energy Mile Calculations

- Assessing Route Difficulty – Correcting Energy Miles for Off-Trail Terrain

- Choosing a Route

- Other Resources

- Using Google Earth to Identify Terrain Hazards (Video)

- Trip Reports

- Image Search

Member’s only version is 5,000 words, includes 30 photographs and other images, and 1 instructional video.

Tying it All Together in the Field with Navigation Tools

In addition to some of the resources I’ve outlined in this article already (Caltopo, Hillmap, Google Earth, and Google Image Search are the four I use the most), here is the gear I might take on a trek to complement my digital route planning process:

- Gaia GPS – I’ve found Gaia to be one of the most functional, fast, usable, and valuable pieces of mobile (smartphone) software to use on a trek. I can download detailed (24k) map sets alone with satellite imagery and GPX files (routes) to my phone and have all of my route planning maps and imagery at hand so I can use them in real time. Gaia and a waterproof (IPX6+) smartphone are the two most valuable advances in backcountry GPS technology, and I find the Gaia Membership to be well worth the money.

- Garmin inReach Mini – Having a device that I can use to communicate with my wife and perhaps negotiate alternate exit points with my pickup ride has given me a lot of flexibility in how I approach backcountry trips. No longer am I confined to hiking a specific as-planned itinerary, and can change my route on the fly as opportunities arise or conditions change. Read my full review of the Garmin inReach Mini here.

- Garmin Fenix 5X Plus – I’m a bit of a data junkie, so anything I can do to monitor my physiological performance while attempting difficult hiking routes over varied terrain goes a long way at calibrating my models for assessing the difficulty of proposed hiking routes. For example, my use of energy mile correction factors above for various terrain types are a direct result of collecting physiological data using tools like the Garmin Fenix 5X Plus.

Conclusion

Many curmudgeons will lament the dawn of the digital age and yearn for a simpler time where one crossed the mountains with nothing more than a liquid-filled compass, a tattered map, a peanut butter sandwich, and grit.

I have to admit that I sometimes slip back into this camp, and enjoy the art of exploration without the influence of those that have gone before me or assist from satellites.

However, I believe that the digital tools that are now available to us offer an increased number of opportunities to push our limits and see more terrain. Their use has significantly improved my safety in the backcountry and my willingness to take calculated risks.

I hope this discussion of the tools that I use, and presentation of how I use them, has the potential to provide some value to you as you embark on your own exploratory journeys of the backcountry.

The rewards of going off-trail include fewer people, more dramatic vistas, and the healing solitude of silence. Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, Montana.

Related Content

- More detail on my navigation kit and the gear I used are discussed in my Garmin inReach Mini Review and my recent article about Navigation Electronics.

- Listen to our Navigation Podcast!

- Luke Schmidt discussed his navigation process in the context of packrafting here, with particular emphasis on using Google Earth.

- Peruse Backpacking Light’s collection of post-trip reports in the BPL Forums.

Disclosure

- Affiliate links: Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be “affiliate” links, which means if you click on a link to one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently make a purchase with that retailer, we receive a small commission. This helps us fund our editorial projects, podcasts, instructional webinars, and more, and we appreciate it a lot! Thank you for supporting Backpacking Light!