designing for the in-between: hybrids, 1990s net art, and a giant floating worm

a half-Filipino talk about dissolving borders and hierarchies

The following is an adapted transcript of a presentation I gave at KIKK 2018.

This talk is about something I’m calling “the in-between.” And to explain what I mean by that, I’m going to do what we often do when we meet strangers: I’m going to talk about the weather.

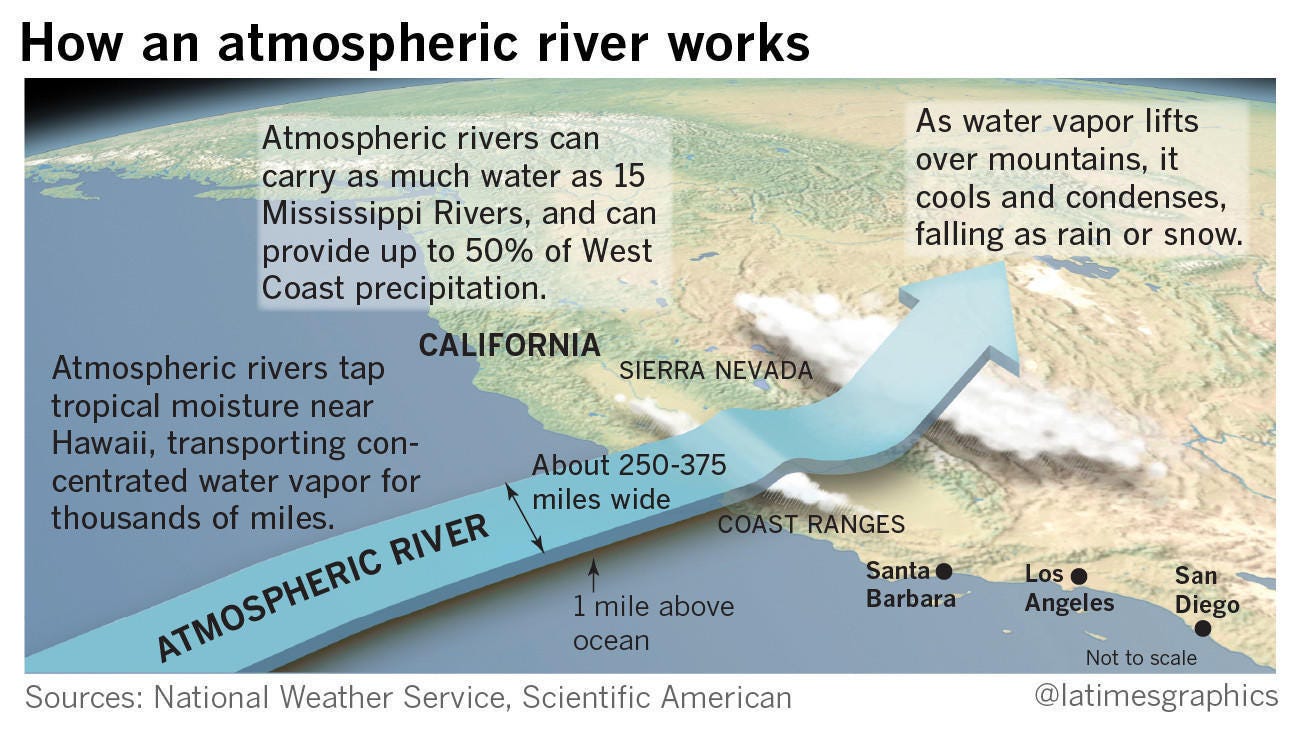

Earlier this year, I was idly flipping through a newspaper and an article caught my eye. It was about an atmospheric river that was set to dump a ton of rainfall and snow on California that weekend. When I looked up what an atmospheric river is, it was exactly what it sounds like: a concentrated pathway of water that enters at one point in the atmosphere and exits (as rainfall) in another. In this case, the rain was going to be coming from the Philippines. And the reason it caught my eye was that I’m half Filipino––but since I’ve never been to the Philippines, it remains sort of a mystery to me.

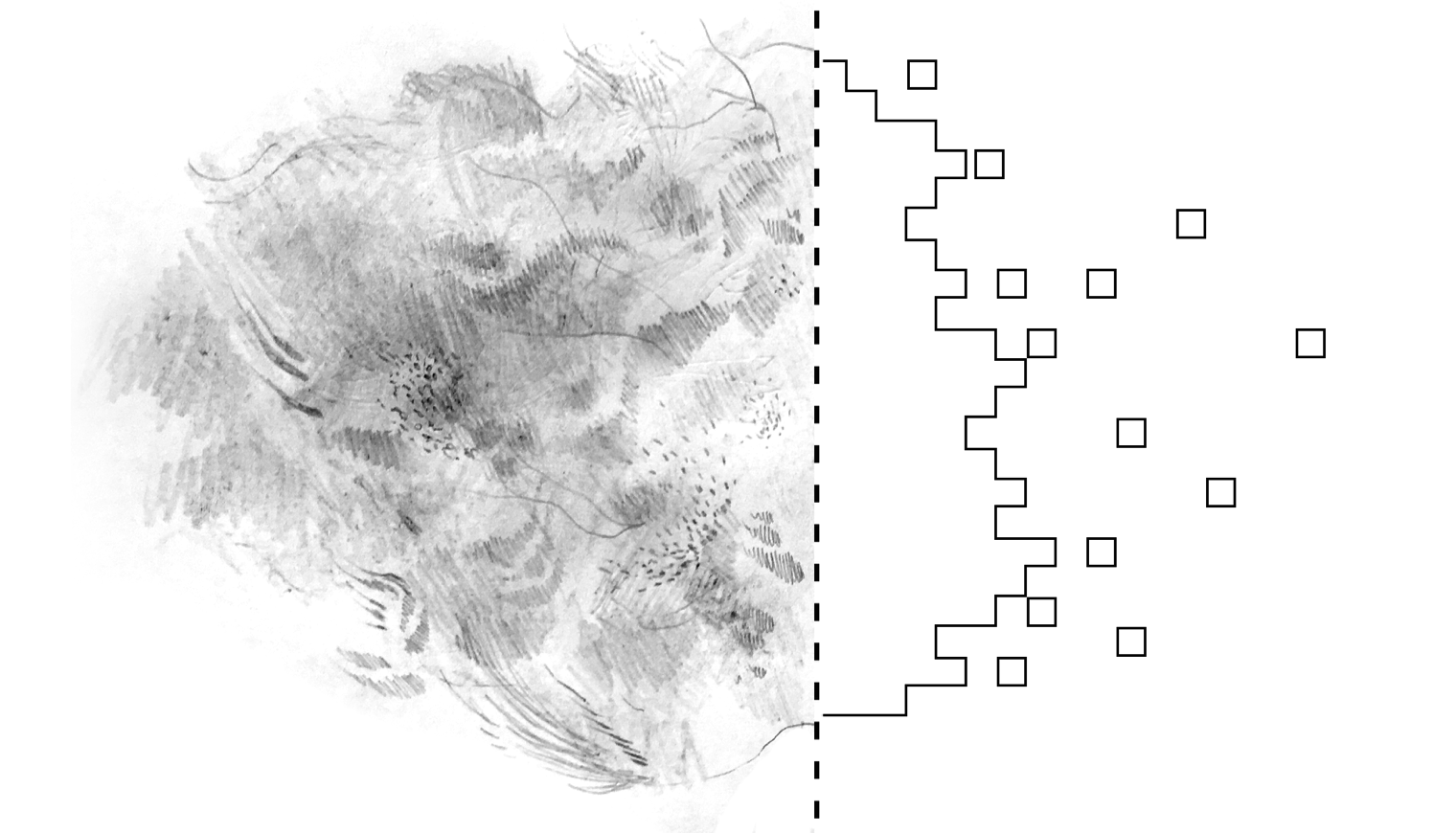

I had never thought about where clouds and rain came from, and I became fixated on this idea of water arriving from the Philippines. So I set a jar outside my apartment and waited. (And waited… and waited… it takes a really long time to collect rainwater.) I wasn’t 100% sure what I was collecting it for, other than to look at it. I thought maybe I should use it to make a painting. So while I was waiting, I texted my mom and asked her what her favorite flower was from the Philippines — her answer was the sampaguita, a kind of jasmine.

I decided to use some drugstore watercolors along with my atmospheric river water to make a painting of a sampaguita to give to my mom. But as I was painting it, I ruminated on something I had come across while researching the sampaguita — which is that even though it’s the national flower of the Philippines, it’s not native to there. It’s actually native to an area in the Himalayas and was imported at some time during the 17th century. Just like the clouds and the rain, this species had arrived from somewhere else.

I find that I gravitate toward phenomena like this: movements that can be tracked and catalogued but never reduced to a true point of origin. As an avid birdwatcher, I always look forward to the arrival of migratory species in the fall, birds with two homes that are sometimes incredibly far apart.

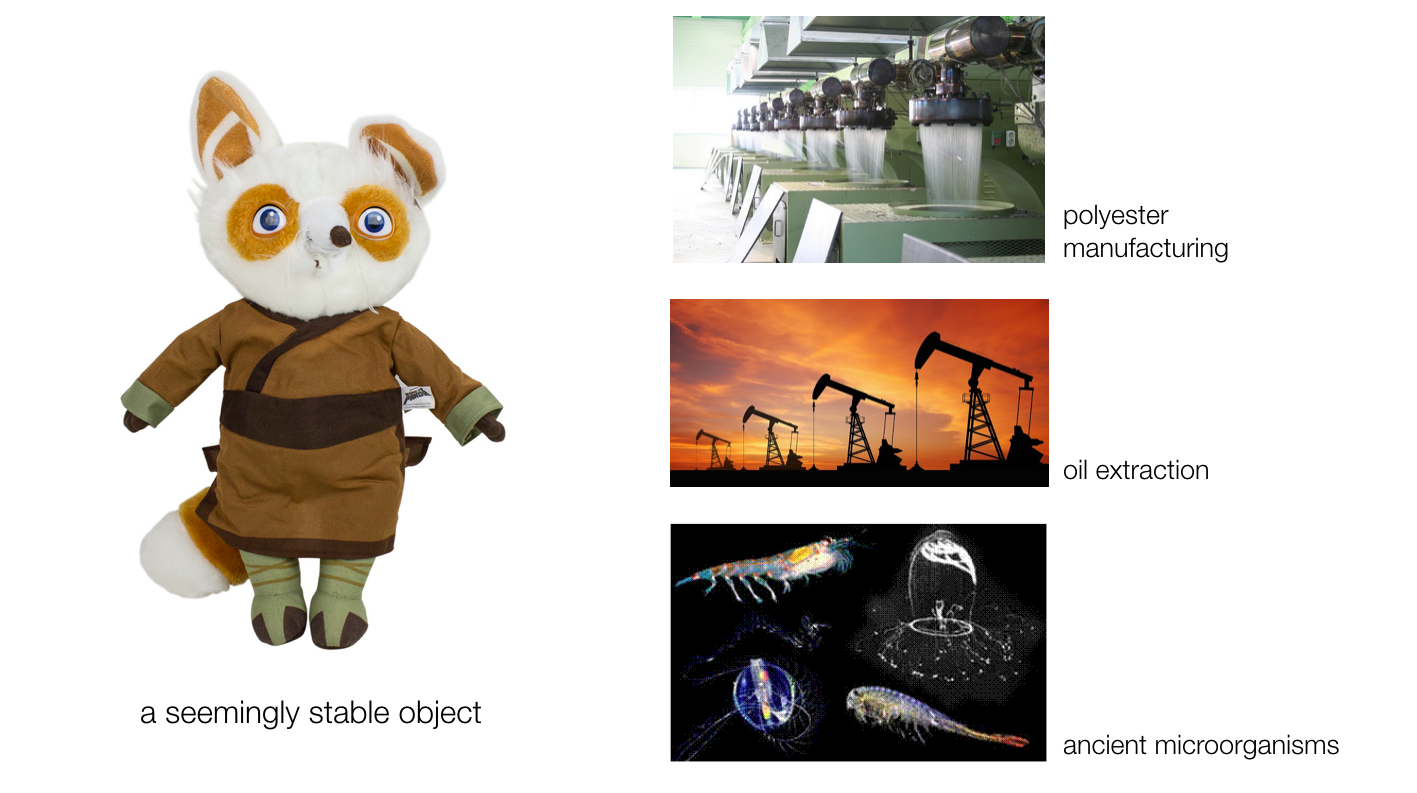

Even when I was an artist in residence at the San Francisco dump, where my ostensible project was to research the manufacturing origins of discarded objects, their actual starting points as things eluded me. Researching a stuffed animal, for example, would force me to consider not only the cultural reasons for its production but the factory, the polyester, the oil used to make polyester, and eventually, ancient marine organisms that made that oil. Not only was it impossible to precisely pinpoint the actual origin of an object, it was also hard to say at what point the object definitively became trash.

As an artist, I explained this tendency by thinking that I was just really into research. Indeed, the nickname the dump workers gave me during my residency was “research lady.” I may be a research lady, but I think there’s another reason I get fixated on origins (or lack thereof).

As a biracial person, it is not possible for me, strictly speaking, to be native to anywhere. So when I think about entities that migrate across borders, or that emerge at an intersection and dissolve at no particular point, they make sense to me and to my experience. In reality, this applies just as much to you as it does to me––maybe I just feel it more acutely because my parents have such different backgrounds. But we’re each a combination, and more broadly, each one of us emerges and re-emerges under different circumstances, moment by moment, day by day. The more I think about this, the more I’ve come to see the fantasies of essentialism and impermeable borders as not only arbitrary, but completely out of alignment with the fluidity of any real situation.

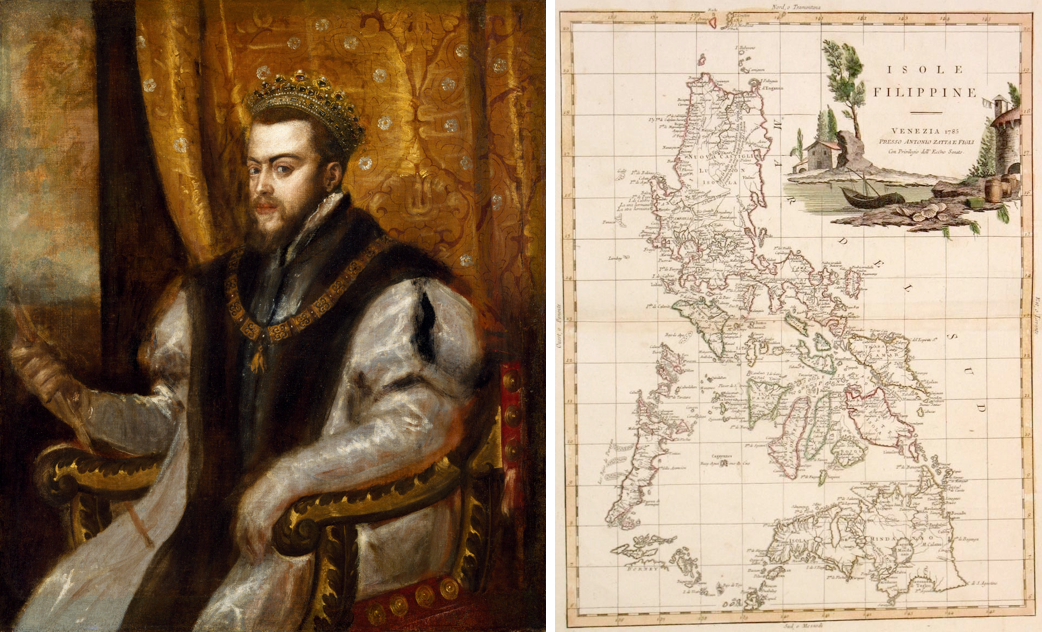

Even if I were to focus on just one half of this story, the Philippines — it slips away from me when I stare too long. What is the origin of the Philippines? Before it was colonized and defined as a country by the Spanish, what we now call the Philippines was a collection of smaller states. Essentially, in the 16th century, some people showed up, drew a boundary around some of the islands, and named this new entity after King Philip II (in Spanish, Rey Felipe II).

The name they gave it was Islas Felipinas, or “Islands belonging to Philip.” It’s kind of weird that to this day, the name for this area, which at the time harbored a mix of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and indigenous animism, is based on the name of a Catholic monarch from the other side of the globe––not to mention one who was busy expelling hundreds of thousands of converted Muslims from his own country during the Spanish Inquisition.

Perhaps for this reason, some Filipinos choose to refer to themselves instead as pinoy or pinay, and some have even suggested alternative names for the country itself. One of those is katipunan, a Tagalog word meaning assembly or gathering (as well as being the name of an 1890s anti-colonial revolutionary society). I like this name because it echoes what I find most fascinating about the country, which is its shape: a conglomeration of seven thousand islands that nonetheless appears to hold together, a unity punctuated by disunity.

Unsurprisingly, this shape has led to an efflorescence of diversity. One place you can see this is in a language map of the Philippines. As I noted in “How to Do Nothing” (about my own inattention to what my mom was actually speaking) these languages are so distinct that you could visit a nearby island and not understand what anyone is saying. Together, the islands contain two-thirds of the earth’s biodiversity and between 70 and 80% of the world’s plant and animals species. This fact is an amazing illustration of how evolution proceeds from niches — from patterns of disconnection and exchange.

But my fascination with the shape of diversity also comes from another part of my background. I happen to have been born and raised in Silicon Valley, and I now teach at Stanford, a place embedded in the local startup culture. This puts me in another curiously in-between position. My job is specifically to teach art to students who are often majoring in computer science, human-computer interaction, and product design. Many of them are gearing up to work at tech companies that value high-performance, results-driven people and behavior––and seem to be grooming themselves accordingly.

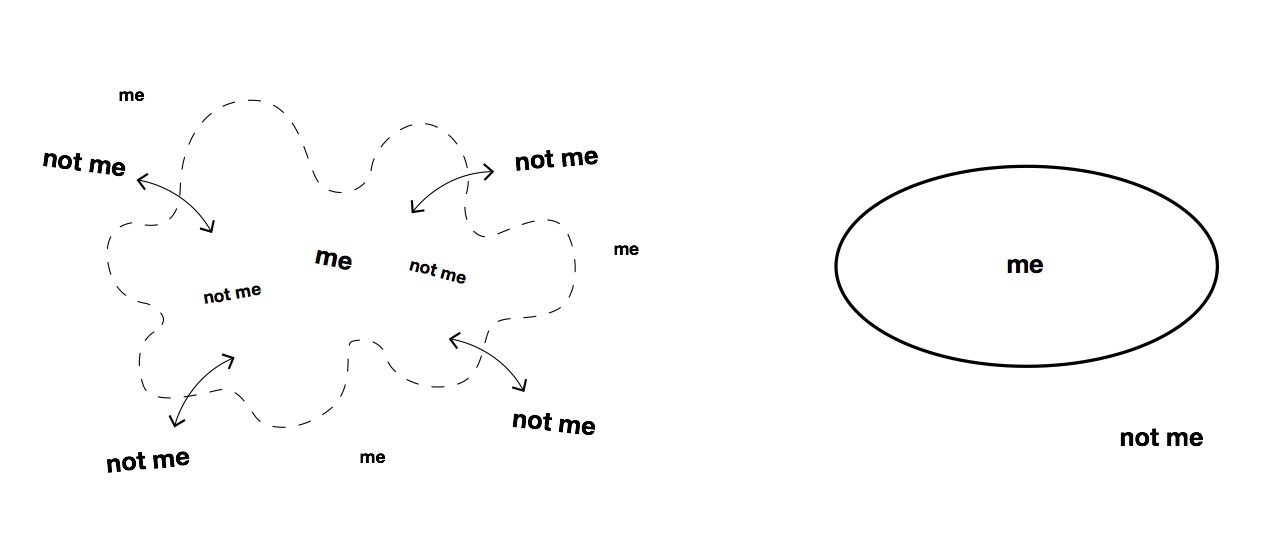

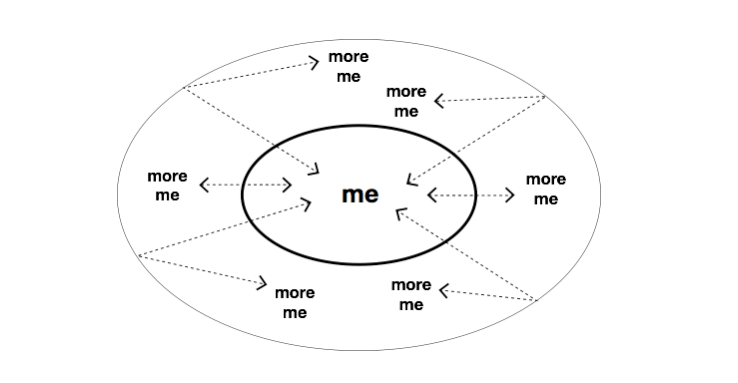

Living and working where I do, I sometimes feel like I’m witnessing (and attempting to forestall) the conversion of people into streamlined algorithms, quantified selves, and personal brands. From what I can tell, it seems that the goal of all this optimization is to arrive at something unified and stable, as evidenced by almost any diagram about personal branding, where everything converges on a single ideal.

What I want to point about about this model is that it figures the self as a targetable point in space, or at least an identifiable process capable of being optimized — either way, it is one thing and one thing only. As it converges, it supposedly strengthens. As Mark Zuckerberg famously said, “having more than one identity implies a lack of integrity.”

As a nature enthusiast, I like to watch the ways that ecology breaks down this kind of logic. The nonhuman world doesn’t care about our categories, our names, or our schedules. Not only that, it’s precisely the points at which nature overflows and slips around these structures that we discover useful and more nuanced models of identity and relationship.

The instances of this I want to touch on here are 1) hybridity, 2) symbiosis, and 3) collectivity. In an effort to make this a properly half-Filipino talk (and also to start to undo my ignorance about the place that half my family comes from) I’m going to pull examples of each of these from both California and the Philippines. I know that there are a lot of designers in this audience, so consider these examples something like a design prompt. I could put it like this: in a time when everything we do, say, and are risks being distilled into a single essence, what would an anti-essentialist design look like? This is an honest question, since you all are designers, and I am not one.

hybridity

I’ll start with an example of hybridity local to where I live. As you might guess from the name, Oakland has a lot of oak trees. The one you’ll find most commonly is the coast live oak, but we also have valley oak, black oak, blue oak, interior live oak, scrub oak, and others. For amateur, aspiring botanists like myself, it can be a point of pride to know your oak trees. But here’s the thing: not only do these different species often grow together, some of them also hybridize, so the point where even expert botanists get frustrated trying to identify them. Sometimes the hybrids are rare — just one or two here and there — but there are places where you’ll find an entire hillside of hybrids with just a few parent species trees.

If you define the boundary between two species as the impossibility of their interbreeding, then hybrid oaks are a problem for the whole idea of a species. In 1878, George Engelmann complained about this in his book, The Oaks of the United States. Just after describing four or five “well-marked forms” in southern California, he added:

…looking around us, the very abundance of material must shake our confidence in our discrimination: within the compass of a few hundred yards we find not only the forms above distinguished, but numbers of others which are neither one nor the other, but which are intermediate between them and clearly unite them all as forms of one single extremely polymorphous species. If one oak behaves thus, why not others? Thrown into a sea of doubt, what can guide us to the correct knowledge?

This problem continues to this day; you will sometimes find the word “controversial” attending descriptions of hybrid oaks because of disagreement about whether they are true species or hybrids. All the while, remember, this question couldn’t matter less to the oaks themselves.

I’ll take my next example of hybridity from the Philippines, the reefs of which are home to a variety of clownfish. There are several species of hybrid clownfish, but one of my favorites is called a white bonnet clownfish, a cross between two very different-looking parent species.

Interestingly, not only is it a hybrid, but within the hybrid itself there is a huge amount of variation; all of the fish on the bottom of this slide are white bonnet clownfish. These unpredictable, one-off designs are the outward evidence of a genetic encounter between one species and another, a place just outside the species boundary where many surprises are apparently possible.

Like the oaks that hybridize because they grow together, clownfish hybridize when they live in the same species of anemone. The host anemones are the common ground two different fish species; without them, encounter and hybridization would never occur.

But the importance of anemones in all this is really not all that surprising, because clownfish not only live in anemones, but are so bound up with them that sometimes it’s a bit hard to draw a line between the clownfish and the anemone––which brings me to the second model that ecology gives us.

symbiotic relationships

Clownfish are kind of a go-to example for a lot of people talking about symbiosis, because in the wild, a clownfish species will only be found with the few anemone species that will specifically host it. Since they are so closely associated and dependent on each other, these species pairs have co-evolved in some really interesting ways.

One of the most interesting of those is how clownfish avoid getting stung by the anemone’s tentacles. Clownfish have evolved significantly thicker mucus layer than neighboring fish. In some cases, the fish actually mixes its mucus with the anemone mucus to create a stronger barrier.

Even species who don’t do this sometimes acquire antigens from the anemone, which some studies have suggested forms a kind of “chemical camouflage for the fish.” Once the fish has acquired these antigens, the anemone is no longer able to distinguish between itself and the fish, and it goes without saying that it doesn’t sting something it considers to be part of itself. Even functionally, the fish act like an extension of the anemone. Not only do they clean the anemone and defend it from other fish, but they even do a kind of wiggle dance in the water to aerate the anemone and help it to breathe. It’s for good reason that the other name for clownfish is simply anemonefish (one word).

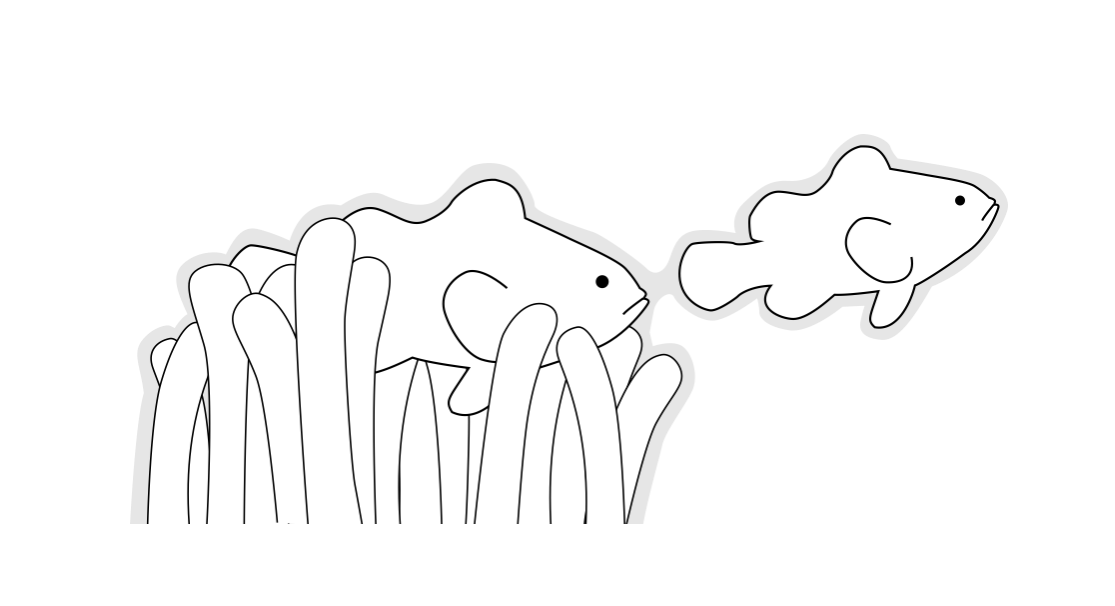

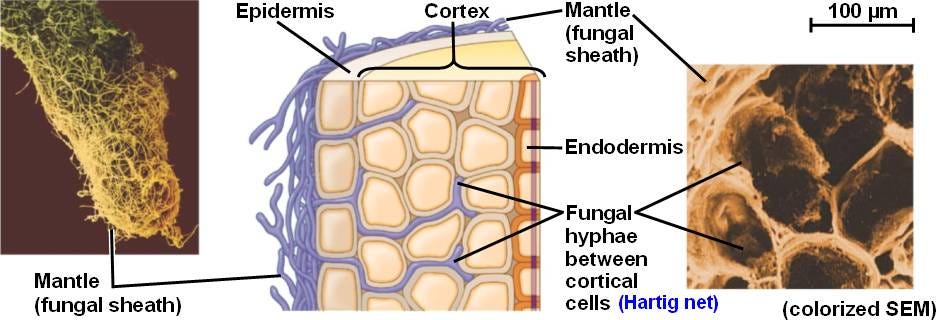

For an example of symbiosis from California, I’ll come back to oak trees for moment. Anyone who forages for mushrooms probably knows from experience that certain types of mushrooms are found under certain types of trees. That’s because our oak trees commonly associate with ectomycorrhiza, species of fungus that grow together with the trees’ roots. This is another mutualistic exchange: the fungus transfers nutrients and water from the soil to the host tree, and the tree provides the fungus with the sugars that it photosynthesizes.

This relationship is 120 million years old, and like the fish and their anemone, when you really zoom in, the line between the two is a bit fuzzy. The fungus doesn’t technically penetrate the root cells of the host plant, but it really gets in there, growing in the space between them. Around the root, the fungus forms a mantle, and it’s been shown that the fungus can affect the shape of growth of the plant’s roots, making them more hospitable for itself.

Meanwhile, the fungus extends further into the soil than the roots would be able to, forming a network that not only brings water and nutrients to the plant but can actually facilitate exchanges of carbon and nutrients between individual trees (sometimes called the “wood wide web”). Now, when I say the fungus is an extension of the tree, I’m not saying that we don’t know what a fungus is and what a tree is. But when we look at the two of them together, I hear an echo of Engelmann’s complaint about something that is “neither one thing nor the other,” in this case, an association that is not quite one thing and not quite two.

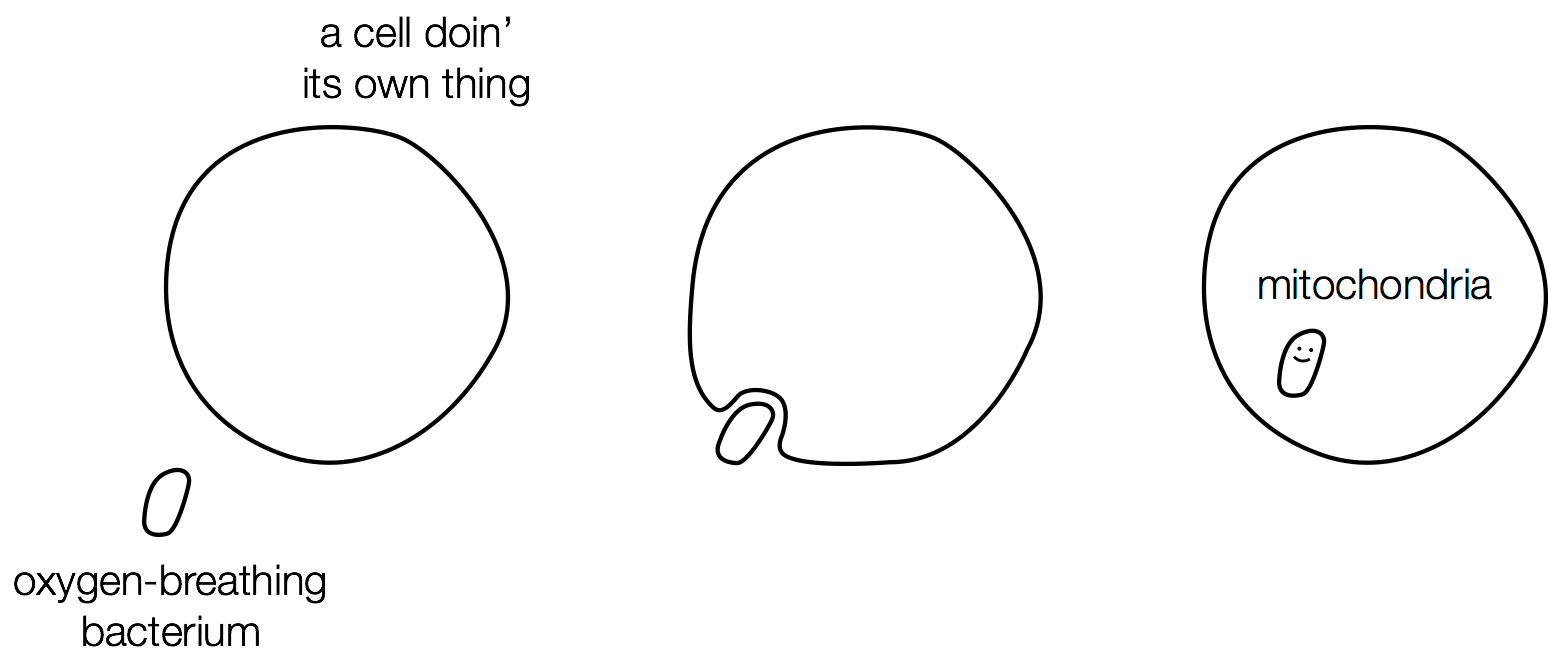

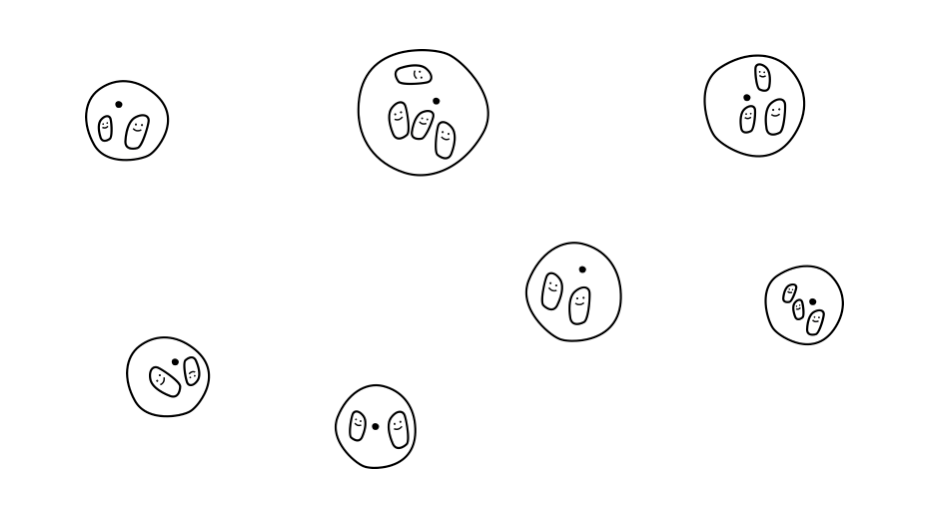

I often think about how almost every one of my cells contains the record of a symbiotic exchange. According to the endosmbiotic theory, put forward in the early 20th century and much advanced by biologist Lynn Margulis, the mitochondria in our cells are the descendants of oxygen-breathing bacteria that entered a host cell at some point and managed not to get eaten. Mitochondria are often referred to as the powerhouse of a cell, since what they used to do independently — use oxygen to make energy––has become the basis of cellular respiration. Cells of ours that need a lot of energy, like muscle cells, contain thousands of mitochondria.

When Margulis was working on the endosymbiosis theory in the 1960s, she was ridiculed, though the idea is now widely accepted. She was further ridiculed for supporting the Gaia hypothesis, the idea that the earth was something like a self-regulating organism — another case of not quite one, not quite many.

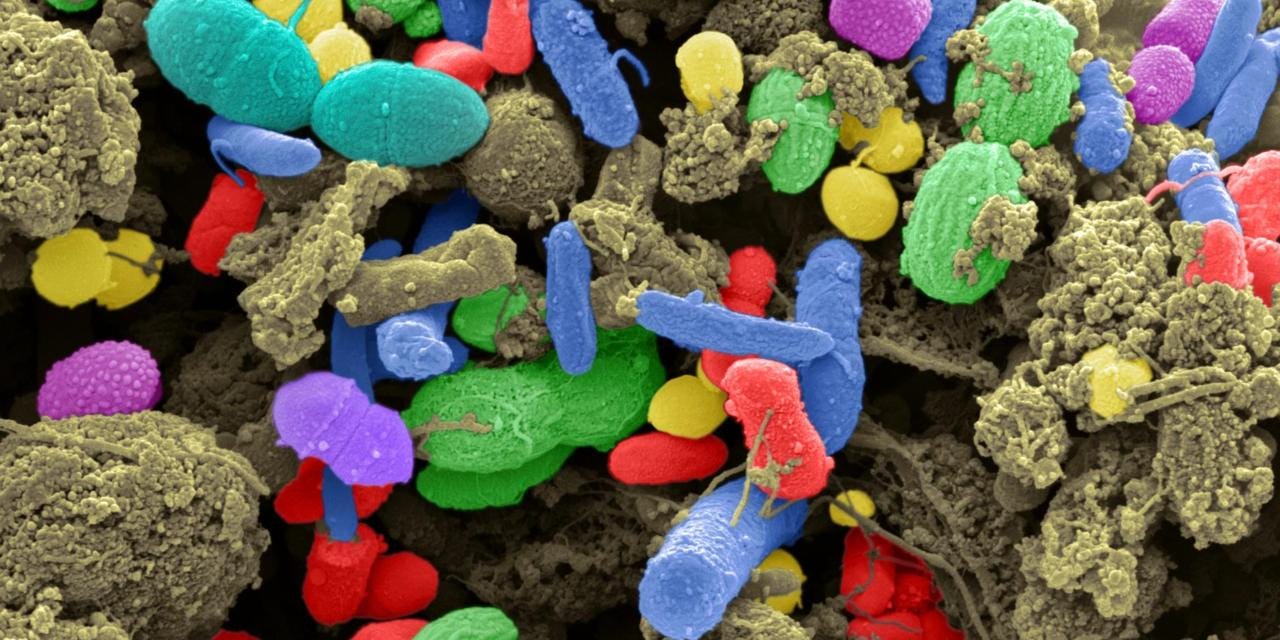

Not that Margulis cared what other people thought. When an interviewer asked if she was tired of being controversial, she answered, “I don’t consider my ideas controversial. I consider them right.” For her, the importance of association wasn’t something to be troubled by, it was something to be celebrated. And it was beautiful. Writing about those other endosymbionts, the free-living bacteria in and on our bodies, she said that “[b]eneath our superficial differences we are all of us walking communities of bacteria. The world shimmers, a pointillist landscape made of tiny living beings.”

collectivity

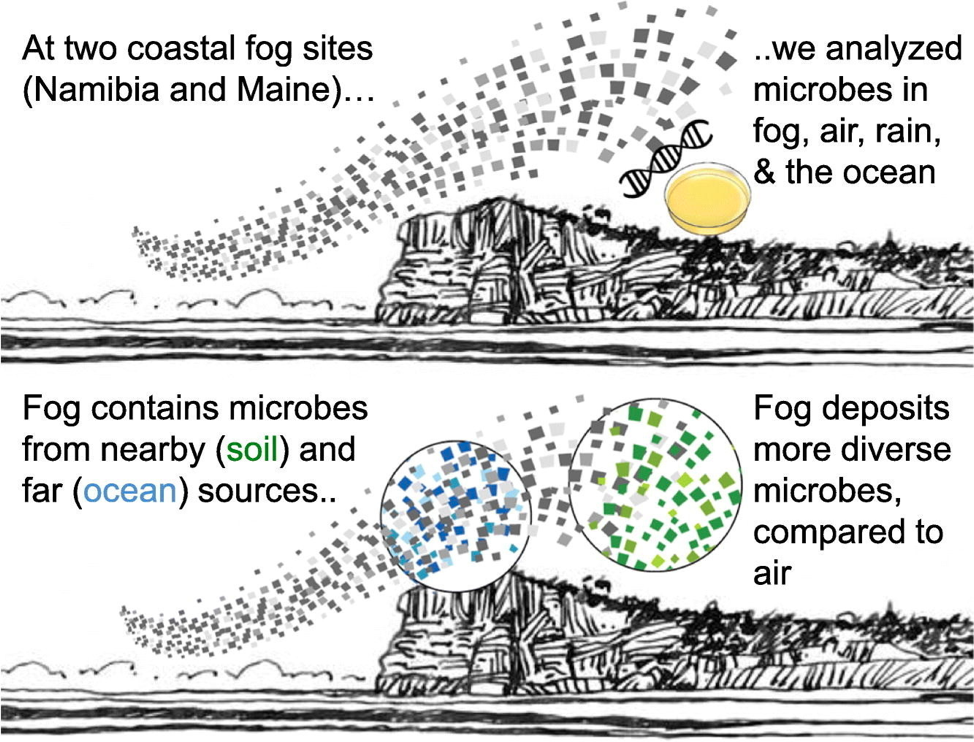

That brings me to the third model I want to look at from ecology, which is collectivity. Besides oak trees, one of the things the Bay Area is known for is fog — which may not seem like a collection at first, nor even like anything at all. But especially in San Francisco, when you’re standing outside of it, the fog coming in from Ocean Beach looks like something, an identifiable mass that is moving, running up against boundaries, pouring over things, and filling crevices. It seems to have a body.

I learned something really interesting about fog recently, which is that it’s not just droplets of water. For fog to form, it needs something called a condensation nucleus, basically a tiny particle of dirt, dust, or salt, really tiny compared to the actual water droplets. Without this, you don’t have droplets, you just have water dissolved in the air. That’s already surprising to me, because it means that you can almost consider fog a mix of land and sea, a thing that emerges at their intersection.

But it’s actually more than just dust or dirt in there — you’ll also find microbes.

In a very recent study, researchers analyzed the microbial composition of fog in two different places and found that they carried a mix of marine, soil, and air associated bacteria — and in fact, marine bacteria could be carried as much as 50 kilometers inland. Sometimes the fog brings something that’s never been there before. The researches write that “fog is a novel ecosystem in and of itself.” For me personally, this makes it possible to see fog as something that’s alive.

After re-mystifying fog for myself, I went looking for examples of biological emergence and collectivity in the Philippines. This search led me to a very strange video of what appears to be a giant floating worm.

The diver who filmed this didn’t know what it was and posted it online, where people initially thought it was a pyrosome, a kind of free-floating sea squirt. But eventually, a biologist identified it a squid egg mass: basically a long gelatinous tube studded with anywhere between 35,000 and 75,000 eggs. These things are pretty rarely seen. Part of that is because they’re semi transparent and hard to observe, but they’re also short lived, since the squid soon hatch and swim away. For that brief period, though, this collection of not-yet-squid floats through the water like some kind of creature of its own.

Amazing as all of these examples are in their own right, I’m bringing them up for a particular reason. I find them to be useful images and metaphors for countering those other much more common images and metaphors, the ones that constantly remind me what I am and what I am not, telling me always to be more me. The hybrid oaks, the anemonefish, and the squid egg mass are tools for imagining a blobbier, more ecological self.

the nature of the net

You may be wondering how on earth 1990s net art figures into all this. Most immediately, net art is one of the things I teach at Stanford, so it’s something I think about it a lot. But I’m also bringing it up because, when I look back at that time, I see processes and identities that couldn’t be so easily pinned down. I see a fascination with communication, reaching out, creating participatory works that emerge somewhere between the artist and the unpredictable participants.

It’s telling, for example, that a lot of important early net art pieces were not from the U.S., they were from Eastern Europe and Russia. These artists were excited about communicating with people outside of their geographical context. In an interview, the artist Alexei Shulgin said it was the first time he’d made work that wasn’t automatically categorized as Russian, adding, “I started to get involved in a number of projects that were cooperations between people who live in different countries and are active on the net. They were not necessarily artists. These activities were based on the idea of communication rather than representation like in more traditional art forms. For that the net works perfectly.”

In contrast to the model of the tortured individual genius, net artists made spaces and connections and watched to see what happened. They mixed themselves together with other things and other people. And because of that, early net art produced some strange forms, what I would call the squid egg masses of the art world. They’re maybe an example of designing for the in-between.

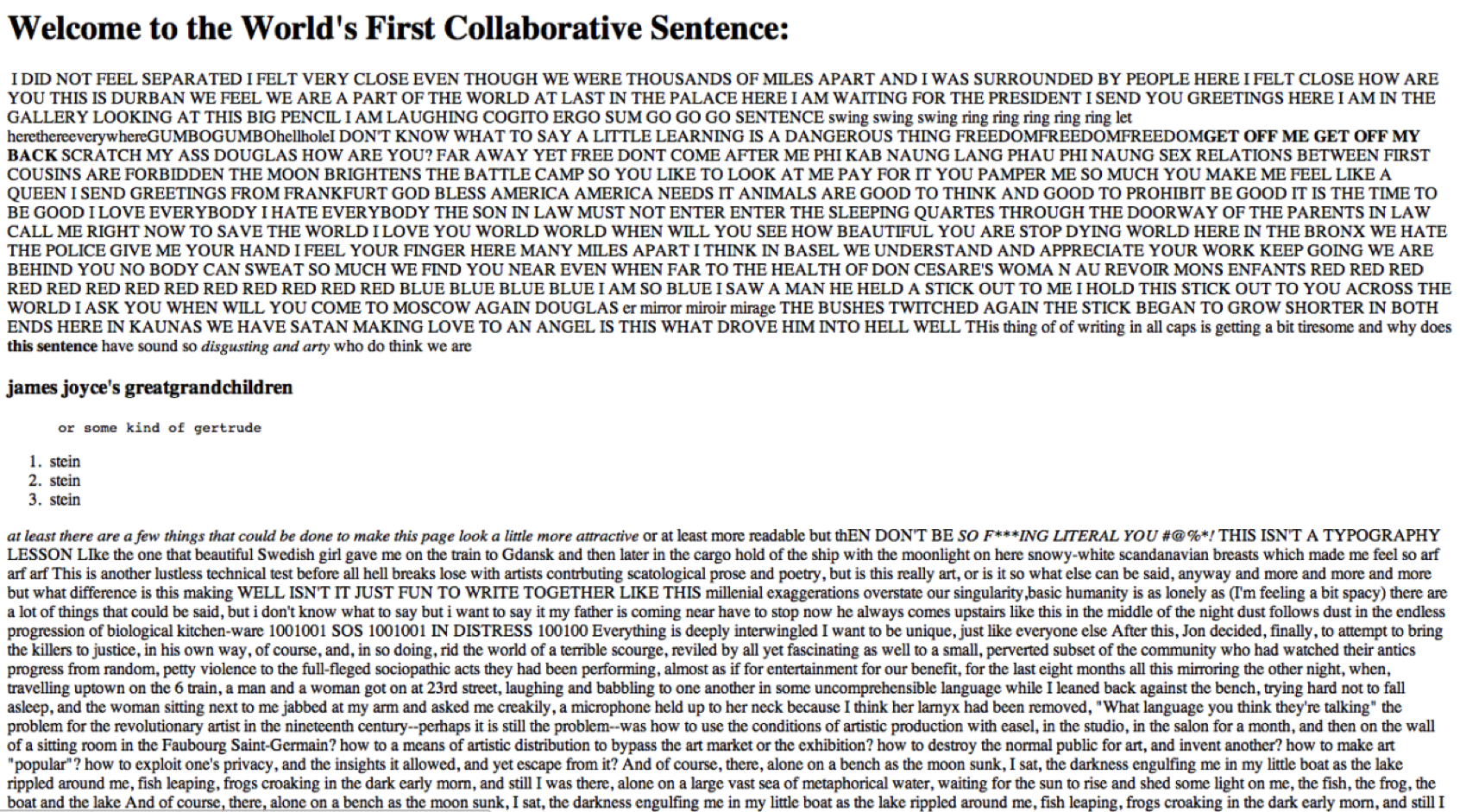

The first form I want to look at is a piece from 1994 (which is now owned by the Whitney!) called The World’s First Collaborative Sentence, by Douglas Davis. It’s pretty much exactly what it sounds like, a space where people could contribute to a never-ending sentence.

In it, you can see people figuring out HTML, learning how to change the font sizes and create lists. It’s not necessarily a meaningful text in a traditional sense, but I think the very beginning of the sentence is very telling:

I did not feel separated I felt very close even though we were thousands of miles apart and I was surrounded by people here I felt close how are you this is durban we feel we are a part of the world at last in the palace here I am waiting for the president I send you greetings here I am in the gallery looking at this big pencil I am laughing cogito ergo sum go go go…

Davis himself, the author not of this sentence but of this idea and this space, described the work in a way that recalls the non-edges of fog and clouds. He said, “The sentence has no end. Sometimes I think it had no beginning.”

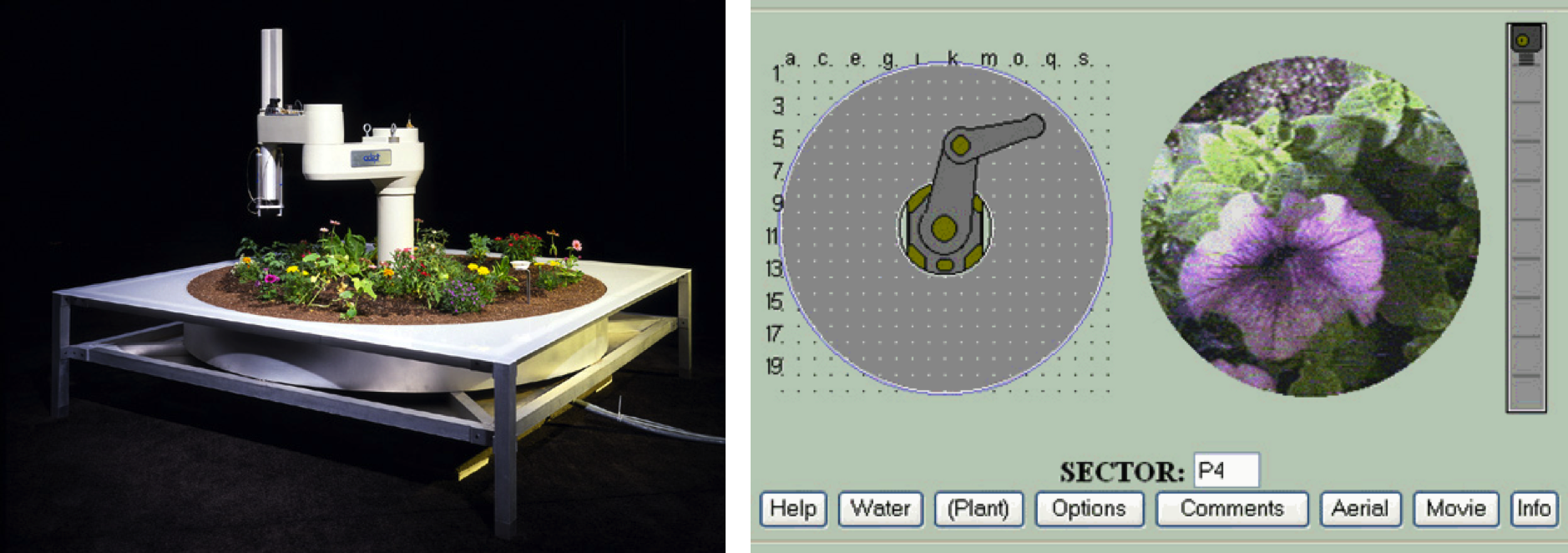

Another experiment in collective expression online was Ken Goldberg and Joseph Santarromana’s project, Telegarden. This was also a website, where users could view and interact with a garden of living plants, planting, watering and monitoring seedlings with what the artists called “the tender movements of an industrial robot arm.” It went online in 1995 and lived for seven years; rights to access the garden were granted to those who agreed to share their email addresses with other members of the cooperative.

A writer in the 1996 issue of Garden Design magazine wrote, “Sowing a single, unseen and untouched seed thousands of miles away might seem mechanical, but it engenders a Zen-like appreciation for the fundamental act of growing. … The unmistakeable vibration of the garden pulses and pulls, even through a modem.” Another arts writer called it “a subtle rumination on the nature of the Commons.” Personally, I find it a beautiful reminder that, unless you’re chatting with a bot, there is always life on the other side.

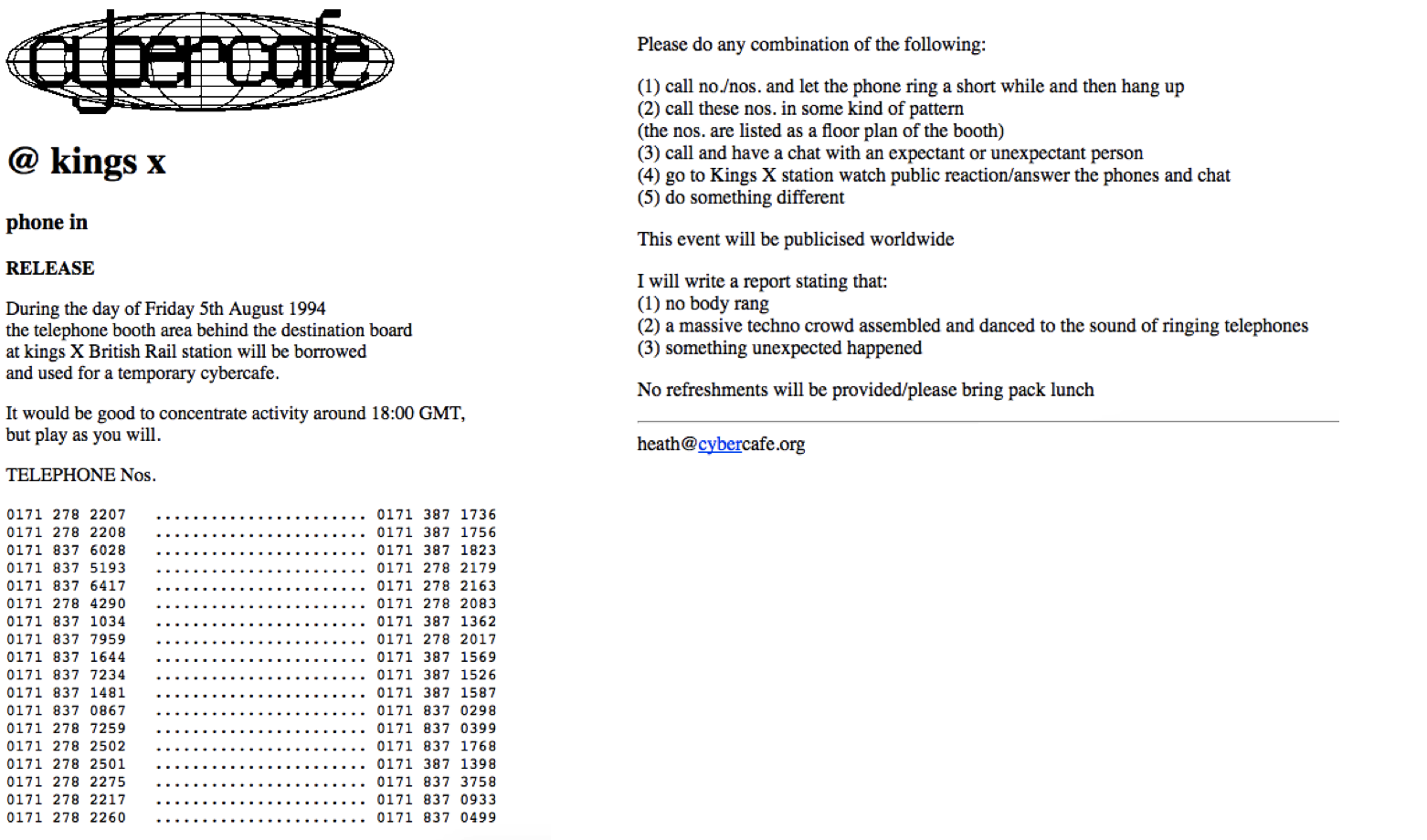

Some pieces mixed people together in physical space. In Kings Cross, an experiment by Heath Bunting, the artist gathered a list of phone numbers, saying that “during the day of Friday 5th August 1994, the telephone booth area behind the destination board at Kings Cross British rail station will be borrowed and used for a temporary cybercafe.” He asked the participant to do any combination of the following: “1) call number or numbers and let the phone ring a short while and then hang up; 2) call these numbers in some kind of pattern; 3) call and have a chat with an expectant or unexpectant person; 4) go to Kings Cross station and watch public reaction / answer phones and chat, or 5) do something different.” He adds, “No refreshments will be provided / please bring pack lunch.”

According to his later report, when he arrived at 3 in the afternoon, the phones were already ringing. The knowing visitors, which he says were “a mixture of nerd, trendy, spy and anarcho double agents” arrived at six. “We had a great time running around answering phones, chatting amongst ourselves and such like, in an atmosphere of freedom and celebration.” And he suggests: “Do one in your town, it’s easy to do and very enjoyable.”

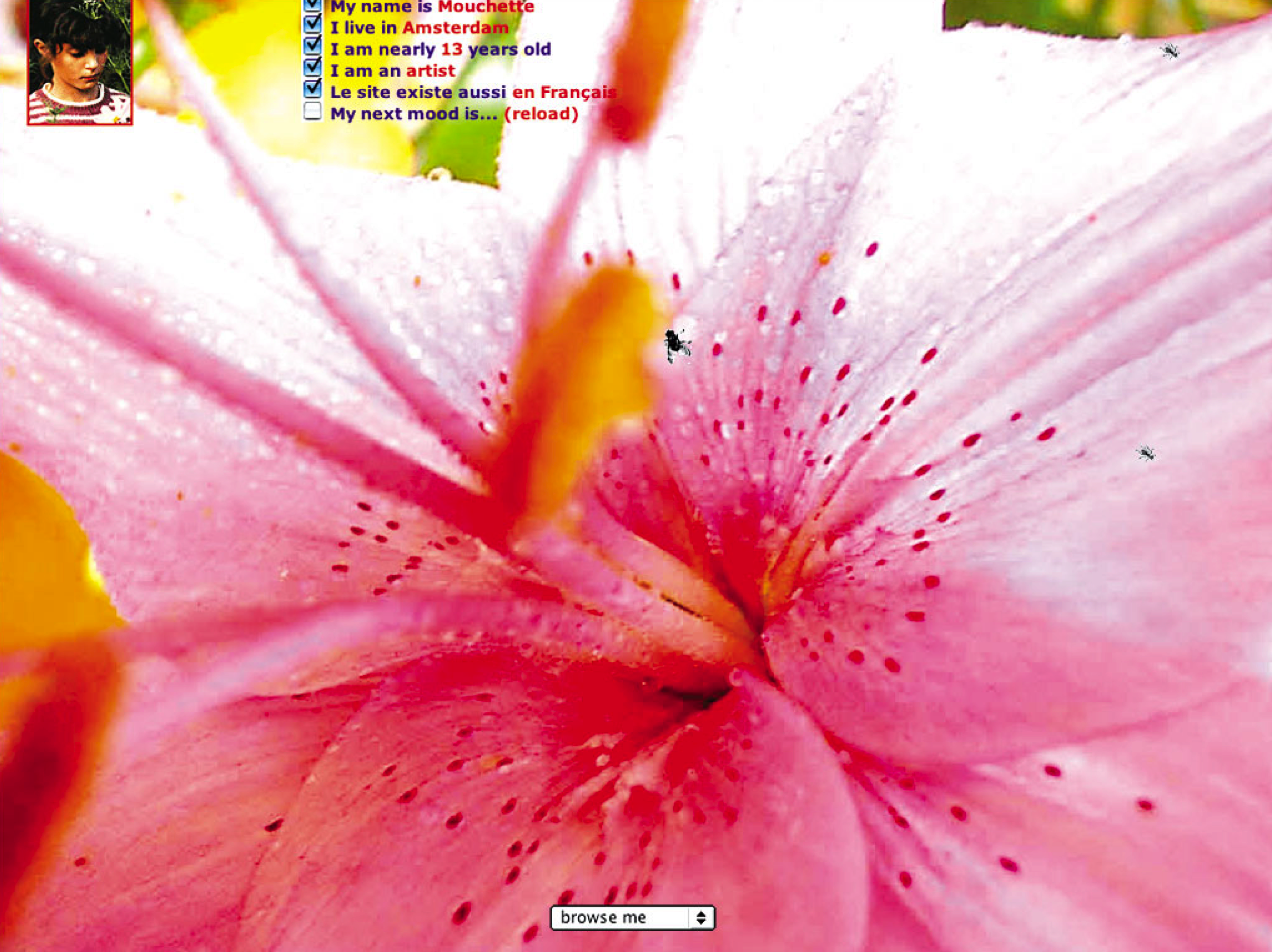

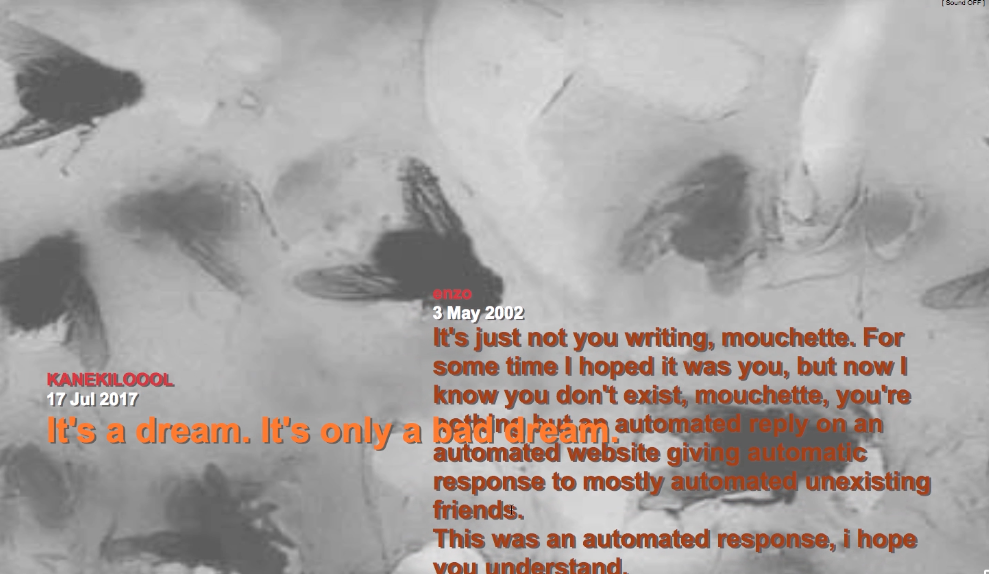

My next example, mouchette.org, is a bit different in that it’s not explicitly creating a collective experience. I include this instead as a demonstration of an elusive or mysterious self, one that can’t quite be defined. Although I’ve credited the artist here, until relatively recently, not a lot of people knew who was actually behind this site. Regardless, the identity that the site represents is not that of the artist, but rather a persona based on a character named Mouchette from a film of the same name.

Navigating this site, especially compared to what we’re used to today, can be a surprising and sometimes uncomfortable experience, not only because what we would now call the UI is deliberately labyrinthine and confusing, but because its interactive features pull us in to this weird story more than we might expect as passive surfers of the net. Even the phrase in the drop-down menu, “Browse me,” feels a little bit too close for comfort. None of the options sound straightforward, and if for example you click on “dead fly,” you get an “it’s me” button that flies around and is diabolically hard to click on.

If you do manage to click it, you’re confronted with text from an eery, disembodied identity that could be Mouchette, the dead fly, or both, and it implicates you directly in killing it by clicking the button. In fact, if you sit through all of this text you will eventually get a form asking you how she can still be reading what you say if she’s dead, and which will directly email your response to this mysterious persona.

And this is where the lines get even blurrier. mouchette.org has been popular for a long time, which means that this question has accumulated a lot of responses. One page of the site, “Lullaby for a dead fly,” confronts the visitor with haunting music and the responses of past visitors, scrolling across the screen like text in purgatory. It’s just one example of how mouchette.org, like any myth, is not quite one thing, but rather an intersection of the impressions, rumors, and iterations of those who encountered her. Mouchette is not so much a person as a collectively maintained aura.

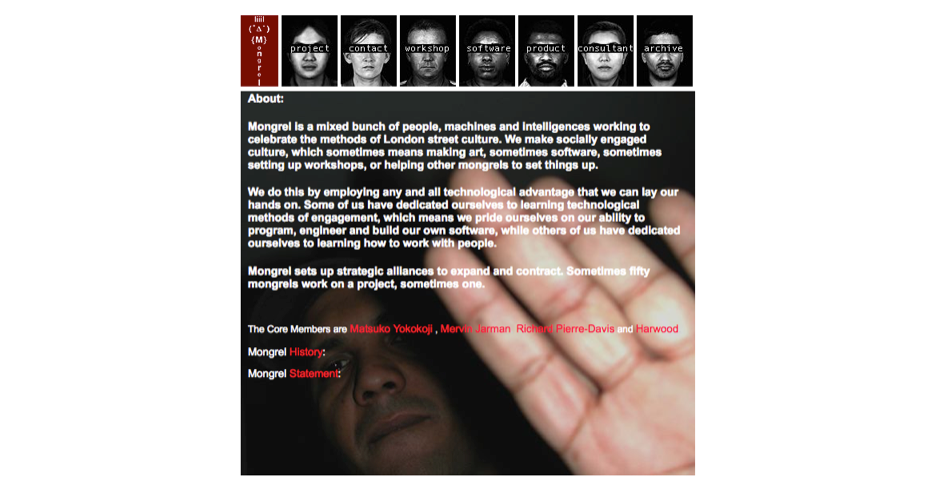

I find that early net art is full of examples like this, where just as bits and bytes were crossing geopolitical borders, the art itself emerged from an intersection of the individual and the collective. You had groups like Mongrel, which called itself a “mixed bunch of people, machines, and intelligences” that “sets up strategic alliances to expand and contract.”

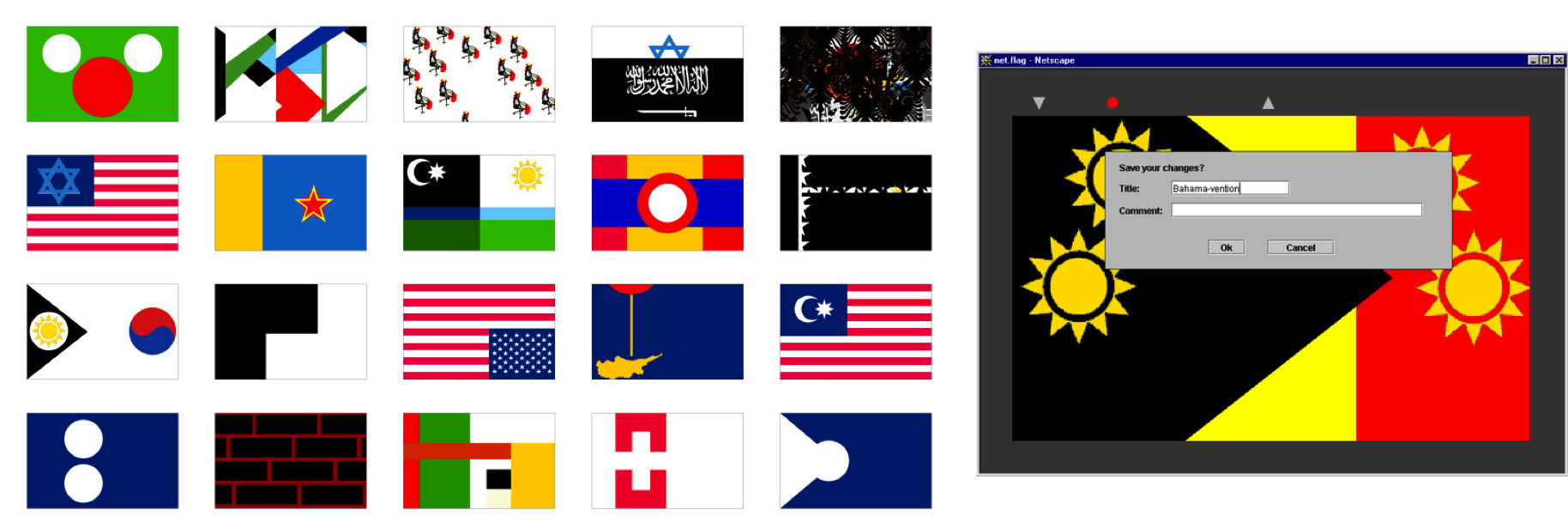

You had Mark Napier’s net.flag, a collectively editable flag for the new territory of the internet, where users could use pieces of existing real-world flags and browse past versions of the net flag.

More recently, there’s the collectively hosted GIF by the net art mainstay Olia Lialina. Each frame is hosted on a different net artist or writer’s website, redirecting automatically to the next one. If a single page comes down, the whole thing breaks.

This might remind you of something: the lost art of the webring, that pre-social-media form by which personal websites of similar interests or topics would join a list, each adding a button on their page that would link to the previous and next sites on the list.

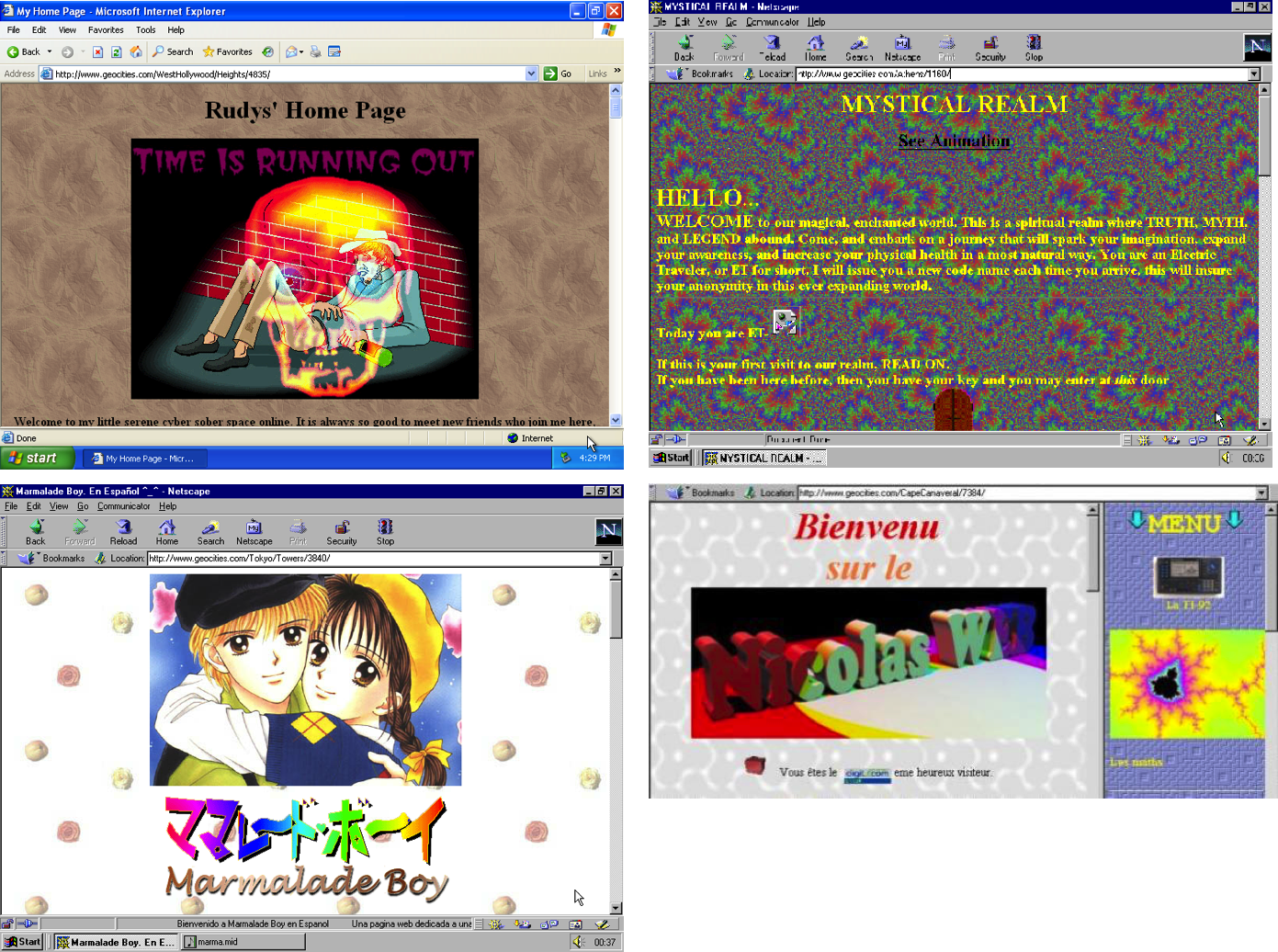

Webrings are interesting to me as nonhierarchical, collectively functioning entities made up of pieces that were, after all, highly individualized. Anyone who remembers Geocities knows that both in aesthetics and content, personal home pages could really be all over the place. (If you don’t remember, just visit One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age, an archive of Geocities pages managed by Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied.)

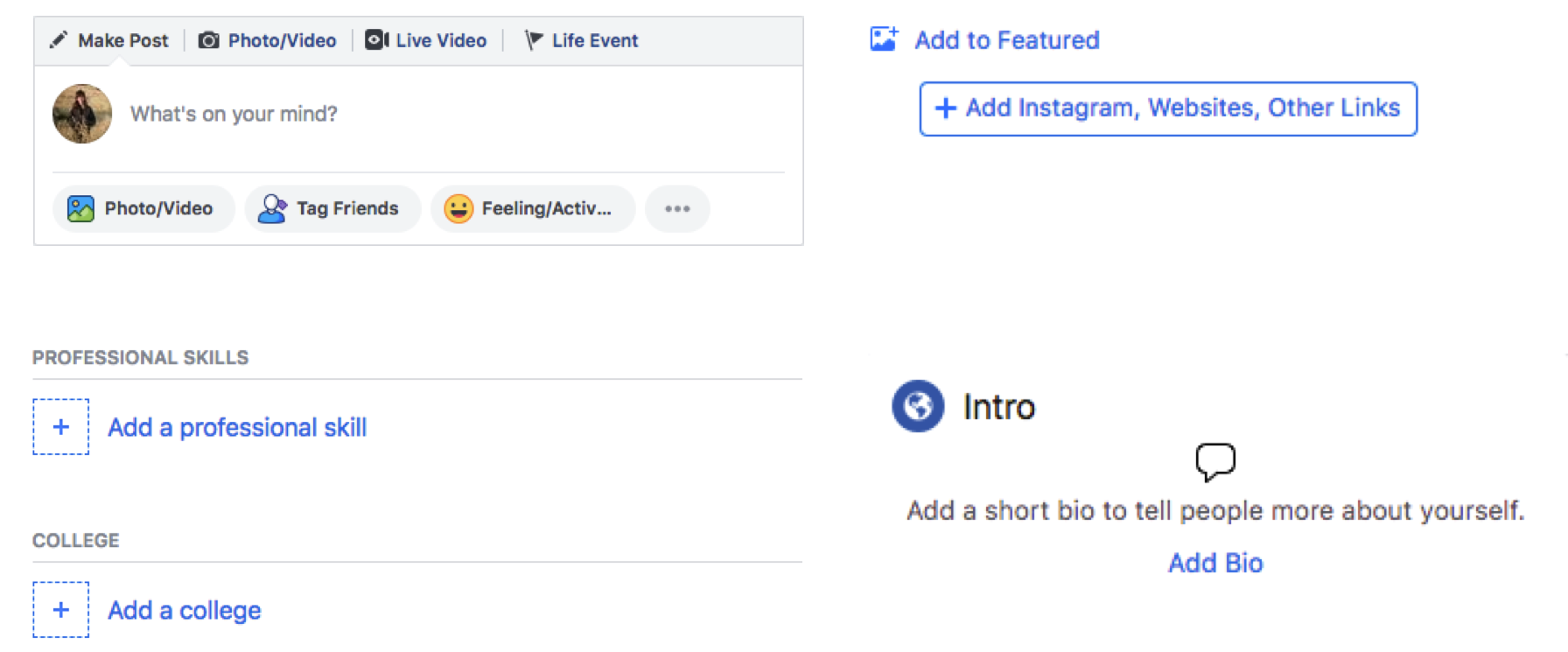

From what I remember as a child of the ‘90s, the surface of this internet was bumpy, inconsistent and surprising. Looking at Geocities pages now, I can’t help but contrast them with a Facebook profile page. With its necessarily cookie-cutter, one size fits all design, a blank Facebook page asks you to provide certain types of information in certain types of frames, both literally and figuratively.

building the beehive

Of course, you can argue that there are practical advantages to this, but any cookie-cutter approach is going to create some problems for that which cannot fit into the cookie cutter. A super obvious example of this happened with Facebook’s former policy that one use their real family name. This policy created problems not only for those who needed to use different names, like transgender folks, drag performers, and victims of domestic abuse, but also for Native American users, whose names are so unlike the norm that they triggered the site’s fake name detection, which would shut down their accounts.

In response to protests in 2015, Facebook changed its policy. That’s certainly a victory, but for me, this instance pointed to something larger, something that’s a problem even for those of us who don’t explicitly find ourselves caught between categories. A one-size-fits-all system means we are only going to see one size, both in others and in ourselves. There is so much that stands to be rendered invisible by any system of knowledge or identity, simply because it doesn’t fall squarely into one bucket or another. The real tragedy happens when, in an effort to be visible, we flee from the less legible realms of the in-between to those ends of the spectrum where we know we will be seen.

If we don’t do this ourselves, the system does it for us. I recently saw a talk by Elizabeth Dwoskin, the Washington Post’s Silicon Valley correspondent. She suggested that the problem isn’t that algorithms are too complicated, but that they’re too simple. She described the way someone who clicks on something out of casual interest will be shown more and more things like that, a process that can quickly lead, among other things, to political extremism. You can try and think of your social media profile as a space of exchange, but really, I would liken it more to a hall of mirrors that eventually pushes you to one end of the spectrum or the other.

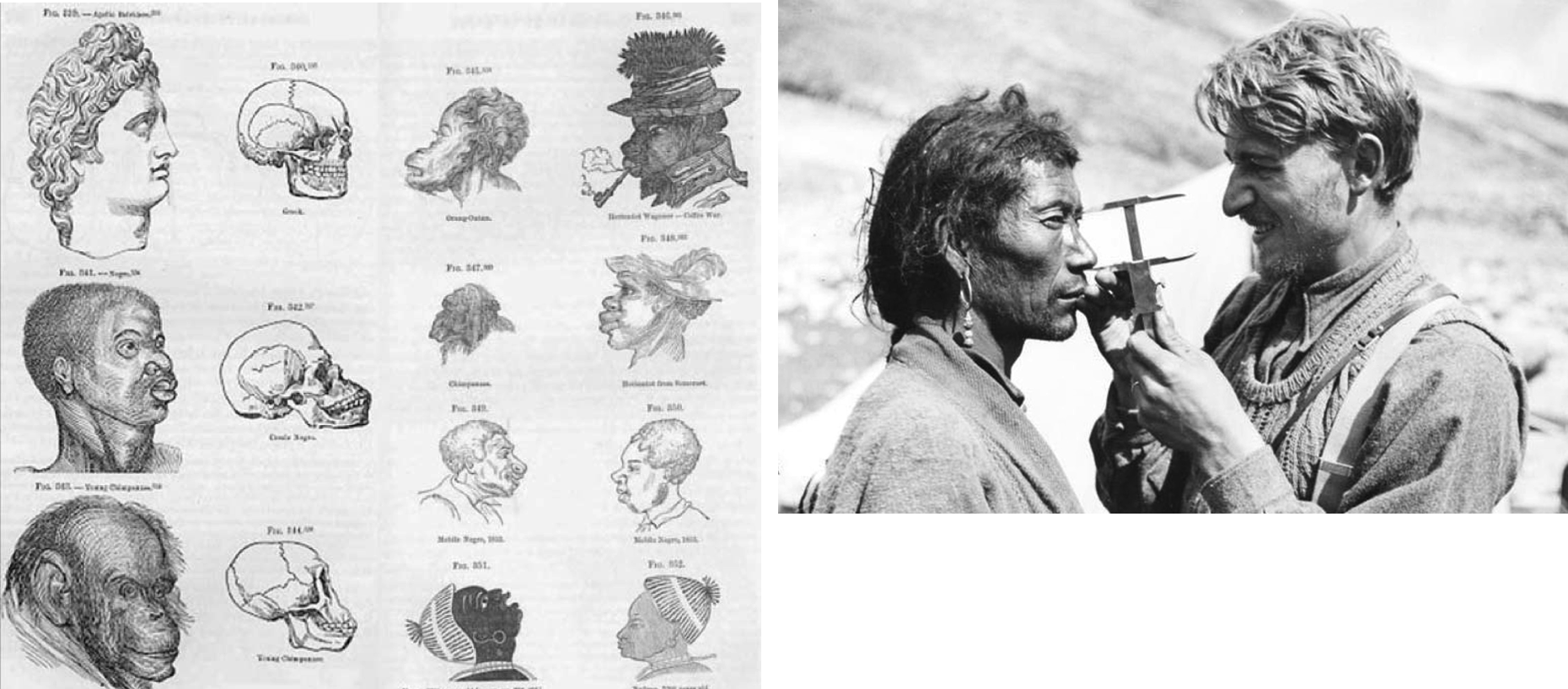

Every cataloguing and monitoring system has its motives. To illustrate this, I’ll turn to another moment in history when names were changed to a fit a mold. In Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott writes about how in one part of the Philippines in the 1800s, Spanish colonial leaders began assigning Spanish names to Filipino residents, using a system called the catalogo, or catalogue, a list of personal names as well as adjectives and nouns. The name assignments were arbitrary, having as little to do with their subjects as King Philip II had to do with the Philippines.

Scott writes: “Each local official was to be given a supply of surnames sufficient for his jurisdiction, ‘taking care that distribution be made by letters of the alphabet.’ In practice, each town was given a number of pages from the alphabetized catologo, producing whole towns with surnames beginning with the same letter.’ He notes that in places that haven’t experienced much migration, you will still find towns where many of the last names begin with the same letter.

What’s important to point out here is why these names were assigned: colonial leaders wanted to make it easier to collect taxes and avoid unauthorized migrations. Naming was the administrative hand of colonial appropriation. This forceful application of abstraction was the means by which the dark, unruly mass of former names, nicknames and identities would be sorted out, sanitized, and affixed to the colonial, capitalist system.

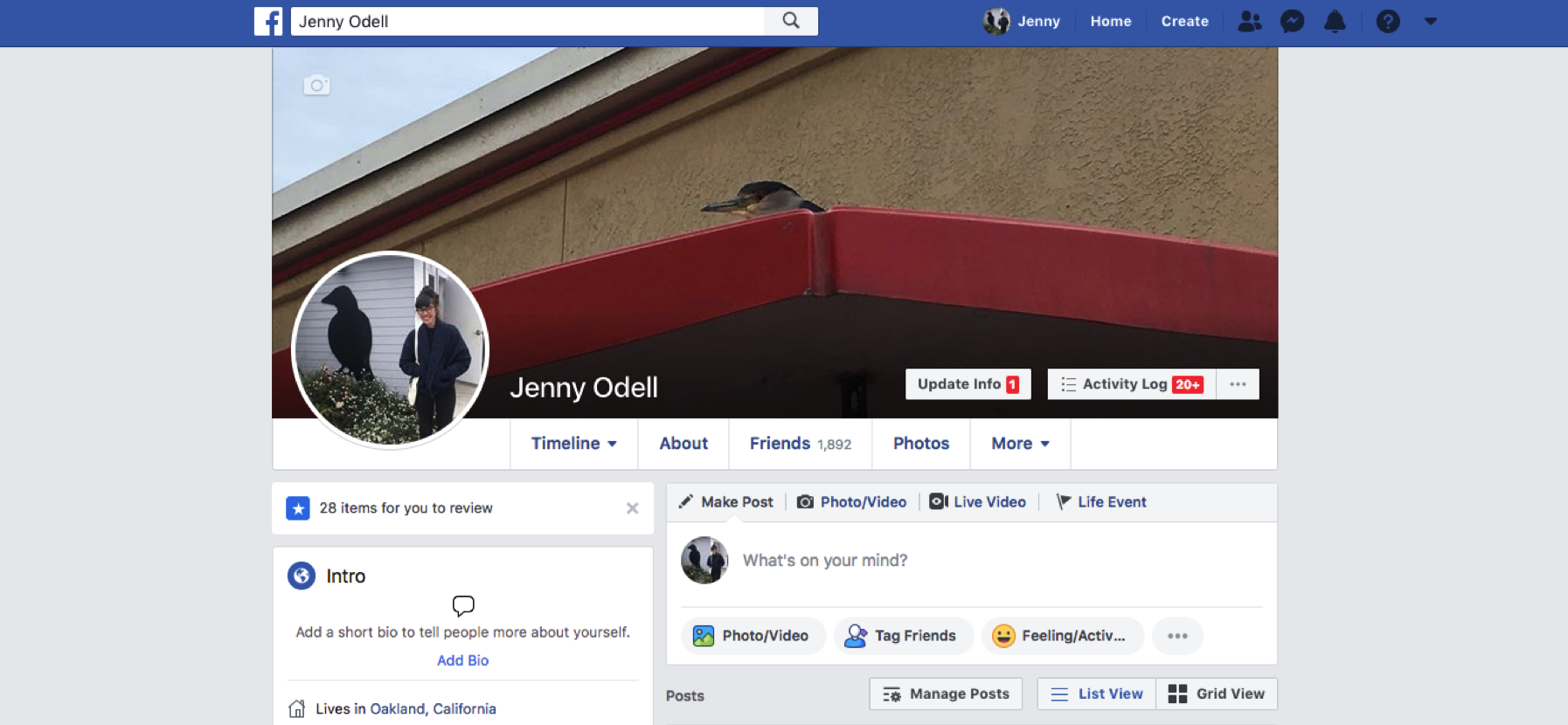

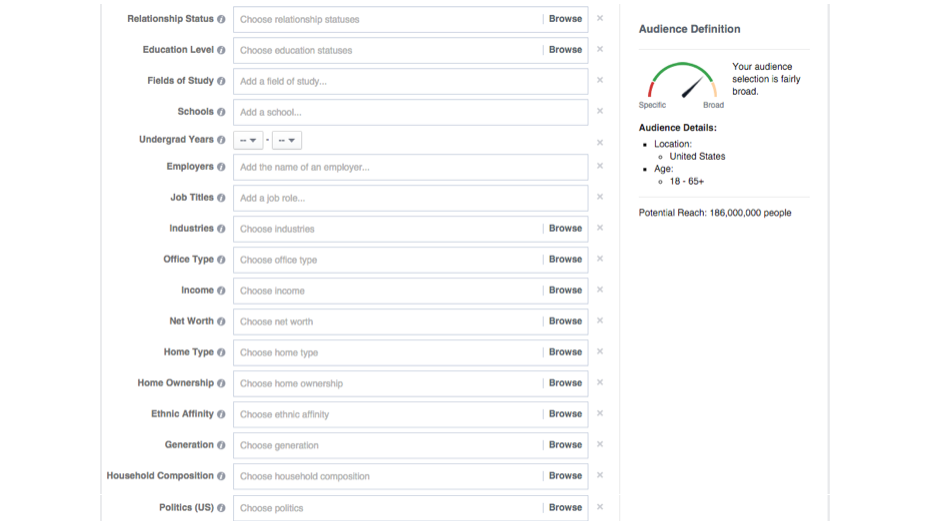

Sounds familiar. After all, the standards we’re asked to fit ourselves into online have their own aims. Commercial social media have a vested interest in pinning us down, reducing us to lists of preferences, and then augmenting the tendencies of those preferences for a reason, which is to make us as legible as possible to themselves and to advertisers. Because of course, my real Facebook profile isn’t this:

It’s this:

Data collection and advertising are the places where my identity becomes useful, where it becomes a commodity, a smooth, stable and interoperable unit of capital. This is the site at which the dark, unruly mass of my identity is affixed to a capitalist system.

I want to stress how much this is an issue of design. In Seeing Like a State, Scott contrasts the natural formation of honeycomb, a complex and organic shape which did not allow for “neat extraction,” with a beekeeper’s box. The design of the slats in the box has something called a queen excluder, a screen that workers can pass through but not the queen, so that she won’t lay eggs above a certain level. The wax cells are arranged in vertical frames, and spacing is calculated so that the bees will leave open individual passages rather than build honeycomb between the frames.

Scott writes, “from the beekeeper’s point of view, the modern hive is an orderly, ‘legible’ hive allowing the beekeeper to inspect the condition of the colony and the queen, judge its honey production, enlarge or contract the size of the hive by standard units,” etc. He uses this image to illustrate the ways in which, as he puts it, “large-scale capitalism is just as much an agency of homogenization, uniformity, grids, and heroic simplification as the state is, with the difference being that, for capitalists, simplification must pay.”

unbuilding the beehive

We should object to this design, because a world with no in-between does harm on every level. It does harm to me as a person with a multifarious self. It does immediate harm to those who try to cross borders and boundaries, like LGBT, trans, and immigrant folks. And it does harm to all of us by depriving us of the exchange of ideas and perspectives that are truly outside of our own. A world with no in-between is like an anemone with no fish to do a wiggle dance for it. It can’t breathe.

On top of all of this, being able to see the in-between is a matter of collective survival. Western corporate-influenced individualism is at odds with the reality that everything is ecological, that nothing and no one can be reduced to its perceived essence, and that truly, no man is an island (not even a billionaire libertarian on an actual island). If we do not understand this now, the climate will soon show us; in fact, it already is.

The conservationist Aldo Leopold once wrote that “you cannot cherish [a friend’s] right hand and chop off his left … If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not.” It’s that “whether we understand it or not” that contains the real wisdom, the acknowledgement that the most important parts of ourselves and the relationships between us may actually be those that are the least legible and the most unruly. Survival may lie not in producing more honey for the beekeeper, but in building that in-between honeycomb — the very activity that that the design of the box prevents in the name of extraction.

Of course, I’m not saying that we should do away with taxonomies and categories in general. I may take particular delight in hybrid oak trees, but I recognize that such systems are a crucial part of how we understand the natural world and organize our knowledge. But we would do well to remember that no system of categories is disinterested or neutral, and that each reflects as much about its maker as it does about its contents. All systems of categories and all standards have a purpose, and sometimes that purpose has been to extract, monitor, divide, and subjugate.

Knowing this, what would it mean to design for the in-between? For shapeshifting selves, for emergent alliances, for ambiguity, for contradiction? What would a social network look like that isn’t extractive, that would not appropriate but rather accommodate individuals and the not-quite-one, not-quite-two nature of actual interaction and identity? What’s the opposite of a trigger? How do you design for patience, for subtlety? Is it possible to build a system that’s as alive as we are?

I don’t have the answer to these questions. I do, however, ask them in a book I have coming out next year (!) called How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. It was in the writing of this book that I began to think about becoming illegible and elusive on purpose, as a strategy––not just living in the in-between, but swimming in it.

This stretchy way of thinking and identifying is well summed up by the way the theorist Donna Haraway defines the word “kin.” She writes, “I think the stretch and recomposition of kin are allowed by the fact that all earthlings are kin in the deepest sense, and it is past time to practice better care of kinds-as-assemblages (not species one at a time). Kin is an assembling sort of word.”

And that word — assembling––brings me back to Katipunan, which as you’ll recall, means assembly. When I think about how I want to figure my identity, the shape of the Philippines, of Katipunan, comes into my mind.

I refuse to be one thing. I’m two things, three things, a hundred things at once, and I’ll be a hundred different things tomorrow. I don’t want the convenience of being collapsed, defined, optimized for legibility. I want to be aerated, blobby, and porous. I want to be the sea around an archipelago, a society of islands harboring uncountable species. I want to be a distributed self, an assembly that assembles with others, that refuses — or more appropriately, exceeds — hyper-rational, neocolonial frameworks, hierarchies, and ways of seeing.

In the meantime, I’m reminded of the legacy of colonialism by my mother’s maiden name, Reyes, which literally means “kings” in Spanish. Thinking about this got me curious about native Filipino surnames. I went looking for them and came across a long list of names in different Filipino languages, some with meanings that stood out to me:

Calajati (Tagalog) — half.

Aglibut (Ilocano)— to roam around.

Julag-ay (Visayan)— mischievous.

Kanlungan (Kampampangan) refuge.

And finally, in my mother’s own language (Ilonggo): Panindagat — sea wanderer.

Sea wanderer. Recall that Englemann, that frustrated observer of hybrid oak trees, had lamented: “thrown into a sea of doubt, what can guide us to the correct knowledge?” It’s there, in the sea of doubt, where you will find me wandering: an amorphous katipunan, a see-through panindagat, a Pinay unmoored from certainty — not just living, but swimming in the dark in-between.

Special thanks to Justin Manley for bringing up Seeing Like a State, and to my mom for help with pronunciation.