I Know the Salaries of Thousands of Tech Employees – Power Trip – Medium

I’m a software engineer with three years of experience, working at Square, a public tech company in San Francisco. I make $130,000, plus $47,500 in stock, for a total of $177,500 a year.

I didn’t negotiate my base salary. I did, however, negotiate my four-year initial stock grant from $150,000 to $190,000. I started my job on February 5. The current value of that grant, which fluctuates by the day, is $412,390.02. If this stock price stays the same until I vest my first year of stock, my “real” annual compensation will be $233,097.51.

Writing all of that terrifies me. Strangers and peers may see what I earn and think I’m vastly overpaid. (“Are you kidding? What does she even do that could justify that kind of money?”) Or they may decide I’m underpaid. (“She must not be good at her job if she’s getting paid that little.”) Inevitably, companies that wish to hire me in the future will see my previous salary and either anchor my future pay at that level, limiting me from pay increases when switching jobs, or opt out of interviewing me at all out of fear that I’ll be too expensive for them.

So why share these numbers? Because we need to talk more about how much we get paid. Fair compensation starts with greater transparency.

Today, gender, race, class, and countless other identifiers play into systemic biases in the tech industry. A 2018 Hired report found that men in tech are offered higher pay than women for the same role in the same company 63 percent of the time. Fifty-four percent of women in tech have reported that they were paid less than a peer of another gender in the same role.

But there’s reason to be optimistic that honest conversations about pay can close this gap. Sixty-six percent of people who became aware of a pay disparity only learned about it by talking to a co-worker about compensation.

The real wealth in Silicon Valley is generated through equity.

Often, when people talk about compensation—what to accept, what to reject, how to negotiate—the advice is “know your worth.” But how? Compensation is locked in a black box for most employees, while the people on the highest rungs of the ladder hold all the information. Often, they can access information about how much the market pays on average for any given role by passing their pay data to firms that gather numbers from many clients and return the aggregated analyses to them. That information asymmetry creates a power imbalance, and only one side — the side with more power — is able to make informed decisions about pay.

Here’s a typical scenario: You’ve interviewed with a company, spent hours doing phone screens, and completed an onsite. You did well and are about to get an offer. The recruiter calls and, of course, asks you for a number.

Here’s where you start to panic. What if your number’s too high? You don’t want the company to not give you an offer — you need a job and already went through the whole interview process, so you don’t want to jeopardize this opportunity. What if it’s too low? You don’t want to undersell yourself, and the compensation you negotiate now, before you take the job, will determine your compensation for years. What are other people with similar qualifications getting paid? You’re shooting in the dark.

Efforts to rectify this imbalance exist (services like Glassdoor, Comparably, and Levels), but anonymous platforms that aggregate compensation data aren’t a substitute for what we really need: a culture where talking openly about compensation is normalized.

On International Women’s Day, I posted a tweet inspired by writer Carina Hsieh and the #talkpay movement. It extended an open invitation to men in tech to share their salaries with me so that I could post them anonymously.

Even today, women and underrepresented minorities are frequently underpaid compared to their peers, and they don’t even realize it because they don’t have many points of comparison. I thought a few people might be willing to direct-message me.

To date, half a million people have seen that tweet. Thousands of people have DMed me. People sent so many salaries that I still haven’t posted anywhere near all the data that I’ve received.

We keep salaries secret because we’re afraid we’ll be penalized for sharing them.

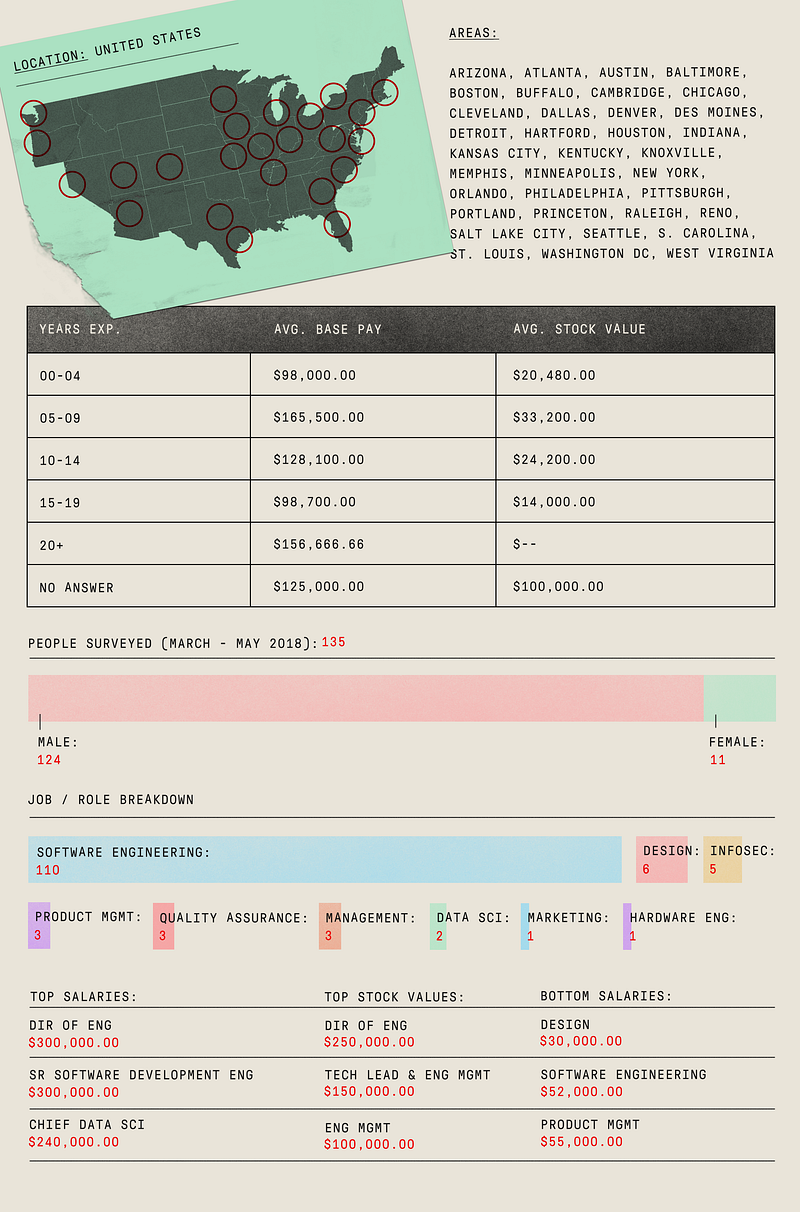

Tech employees from around the world, in all kinds of roles, sent me their salaries. But because I’m a software engineer in the Bay Area, that’s the biggest data set I have. So, how much do men in software engineering in the Bay Area get paid? Here’s my contribution to the pay discussion:

Software engineers build all the websites and apps you use every day. Software engineering roles in the Bay Area often start at six figures: $120,000 is a typical base salary for a computer science major who just graduated from a four-year college, a standard set by the big public tech companies. That new-grad pay might be lower at a small startup, but often even startups will pay six figures. Early stage startups pay the least, and the really mind-boggling compensation numbers begin to appear only at the biggest “startups,” like Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb.

One big differentiating factor between startups and public companies is equity. Often, startup equity isn’t worth anything in the end, but at public companies, equity represents a huge part of compensation. Base salaries rarely rise above $400,000 — in fact, I haven’t seen it yet — but stock can double or even triple an engineer’s overall compensation. And unlike salary, stock can grow dramatically in value, which can be true if you’re a Google employee who’s watched the stock price skyrocket or if you’re the first engineer at a startup that’s been acquired for a big price tag. The real wealth in Silicon Valley is generated through equity.

Facebook and Google, in particular, pay the most aggressively for in-demand talent. Despite a competitive market, if you hear about an engineer with a total annual compensation of $750,000, that’s far from typical. Odds are they work at Facebook or Google and are one of a select few people in the world with the industry experience and expertise to do their jobs. They’re the people in “golden handcuffs”: They could get a job anywhere, in theory, but they can’t leave (or, at least, they think they can’t leave) because no competitor could match their pay.

Often, people worried they could be fired for sharing how much they get paid.

If I were to guess the average total compensation (base salary, equity, and bonuses) for a software engineer in the Bay Area, it’d be between $150,000 and $200,000. That estimate is supported by the data I’ve received through Twitter, where the median total compensation is $183,750. According to Glassdoor, the average engineer’s base salary is $137,000, with a $11,000 bonus, and that doesn’t include stock compensation.

It’s a lot of money, so it’s no wonder that it’s a sensitive topic of conversation. Still, I wasn’t prepared for how afraid of repercussions the people who sent me their compensation numbers would be. Many people who responded to my thread repeated again and again that this information needed to be anonymous. Several even asked to redact details as vague as their city or job title, just in case they were identifiable to someone, somewhere. Often, people worried they could be fired for sharing how much they get paid.

Attitudes around pay transparency are a sign of a seriously broken culture. How we’re compensated shapes everything about our day-to-day lives: where we can live, what we can do, how much freedom we have. It’s entirely in our interest to be more informed about where we stand when it comes to our pay, and yet we keep that information secret because we’re afraid we’ll be penalized for sharing it. In an industry that’s supposed to value transparency so deeply, we’re falling short where it matters most.

Let’s change the power dynamic. Talk to your co-workers, your industry peers, and your friends about how much you get paid. Talk to the women and underrepresented minorities on your team. Don’t just talk about salary; talk about your total compensation, including equity and bonuses. Talk about the process, like how your pay has changed over the course of your career and what it was like to negotiate the end offer you got. Invite them to do the same.

A common perception is that companies have all the power in the job market because they have the jobs. But employees are the ones who provide the skills and experience companies need. Knowing how much you should get paid gives you some power in a system that often doesn’t favor you — and you should use it.