How do you design an effective growth team? – Dropbox Design – Medium

Lessons learned from building the Dropbox Paper growth team

Our industry is in the perpetual pursuit of that one individual who works better or faster, who is more productive or creative. No doubt, having smart engineers, designers or product thinkers in a team is important. But the myth of the lone genius, who works in solitude, isolated in a room for months, and then emerges with the perfect solution is just that… a myth. The truth is messier. Doing great work means bringing together groups of talented people and finding ways to enable them to shine as a team.

At Dropbox, we’re always thinking of ways we can make our teams successful. And creating a growth team for Dropbox Paper was an opportunity to do just that. Not only because assembling a well performing team takes time and iteration. But also because growth teams need to develop special processes that enable them to define, test, and validate hypotheses fast.

In the process of building out the Paper team, we identified two key areas for building a highly effective growth team: (1) developing processes for collaborating with different disciplines in your team and with other teams and (2) moving fast, without breaking things.

I. Develop good collaboration with people on your team, but also build relationships with other teams

1. Doing great work with different disciplines in your team

In your team, there are probably quite a few disciplines that you work with daily as a growth designer: research, engineering, marketing, UX writing, product or analytics, to name a few. To do great work, it’s important to collaborate with all these disciplines. But, for now, let’s zoom in on two big ones for growth: engineering and product.

Working well with Engineering

(or how growth designers can get superpowers)

Working well with engineering means almost never hearing “No way am I able to implement that. Design something else!” A good way to make sure you do hear those words is operating as the “lone genius” — thinking through a problem and coming up with a design solution by yourself, or only with other designers.

As we’ve built the Paper growth team, we realized that we couldn’t afford this type of misalignment between engineering and design if we wanted to move fast. We needed to involve engineering early in the design process and be transparent about design solutions we’re considering. In our day to day work, that means that:

- When a designer starts a new project, they meet with the engineer to align on the goals of the project. They discuss the main flows in a project, and important technical constraints.

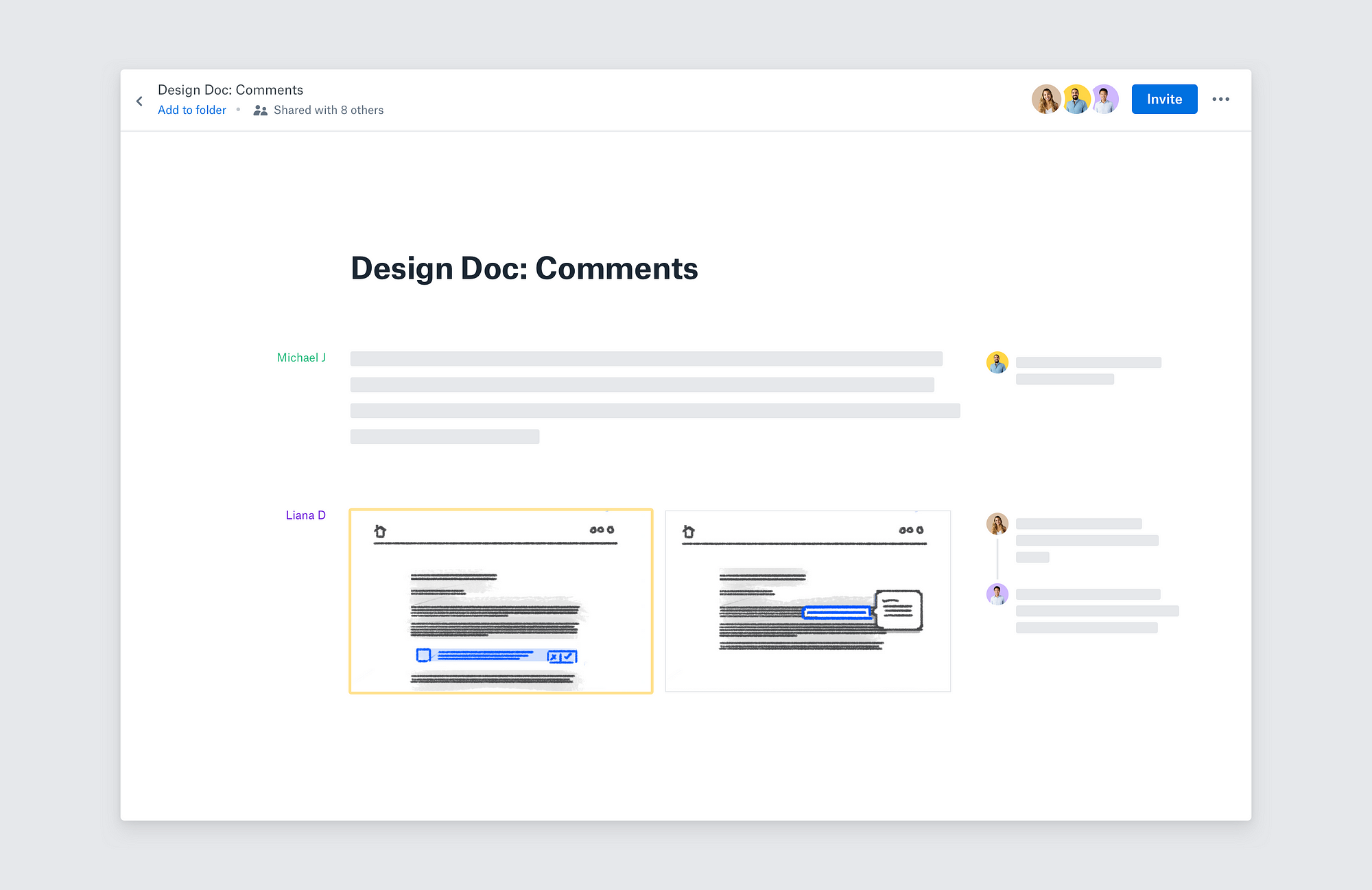

- As the designer starts wireframing different options, they share them with the engineer. Designers usually add their work to design docs that outline pros and cons for each option.

- The designer also invites their engineer to design critiques, to get their thoughts on ideas they’re exploring for the project.

Over-communicating with engineering throughout the process definitely helps reduce misalignment. But it also helps us do better work. That’s because:

- Engineers bring unique technical expertise to product thinking. They point out edge cases that impact the design and they help shape a feasible design solution.

- Having an open dialogue with the engineer helps us align on experimental quality. By talking with engineers, we can make sure that design tradeoffs we make don’t impact learnings we want to have with an experiment.

- Working on a design problem and shaping a solution together with the engineer gets them invested in the project and excited about building it.

Working with Product

(or how to maximize your impact as a designer)

Just as we keep communication open between design and engineering, we also make sure that design contributes to product planning. There are two main areas where designers support product. First, designers participate in high-level product thinking. Second, we help plan individual experiments.

For high-level product thinking, designers suggest new surfaces or areas where we can run experiments. Based on projects we worked on in the past, we propose new or follow-up experiments. And this makes the work better. Designers empathize with users, so we can advocate for running experiments that address user problems, in addition to moving metrics.

When it comes to individual experiments, designers help set goals for our experiments. We do this by working with product managers to define hypotheses and predictions for each project. Once we start design work, we share process-generated artifacts with our product managers: research, wireframes, or high fidelity work. Sharing work early and often is super important, because design work can influence or even change the goals we have for a certain project.

So, designers working closely with product helps ensure that:

- Experiments we’re running are targeted at solving real user problems.

- Designers are never handed off product specs without having understood the rationale behind experiments we’re working on.

- When we start work on a project and we gather new information in the design process, we adapt our experimental goals accordingly.

2. Building relationships with other teams

As a growth designer, working well with other disciplines on your team is important, but it’s not enough. A unique challenge that growth teams face is that they don’t own surfaces, they own experiences. That means that growth teams need to cultivate relationships with those other teams on whose surfaces they’re running experiments.

For example, on Paper growth, we recently ran an experiment where we added education about Paper in Dropbox onboarding. To do that, it was important to have a good relationship with the team working on Dropbox onboarding.

Communicating the value of a certain experiment to other teams can be tricky. One way we approach this on Paper growth is that we try to find common ground based on shared goals that our teams have. And the way to do that is to focus on the business and on the user.

- On the business side, to find shared goals, we try to align on high level goals that our organization or company has.

- On the user side, we focus on user problems. If our experiment is addressing a user problem on the surface owned by another team, that team will be very happy to work with us to solve that problem.

II. Move fast, don’t break things

Having great processes for working cross-functionally gets you halfway there in creating an effective growth team. Working well is important, but you also need to work fast.

A growth team that takes a very long time to launch experiments is unlikely to have a good fate, for two reasons:

- First, growth teams have very clear metrics they try to improve. If those metrics don’t move, it’s obvious quickly that something isn’t working.

- Furthermore, product growth is, almost always, an immediate priority for the business. If a growth team doesn’t deliver on that, there’s something wrong either with the product / the target market, or with the growth team bringing that product to market.

So, there is another important dimension to consider in building a growth team. And that is how you enable the team to move at high velocity, while maintaining a high bar for shipping designs of great quality.

1. How to move fast

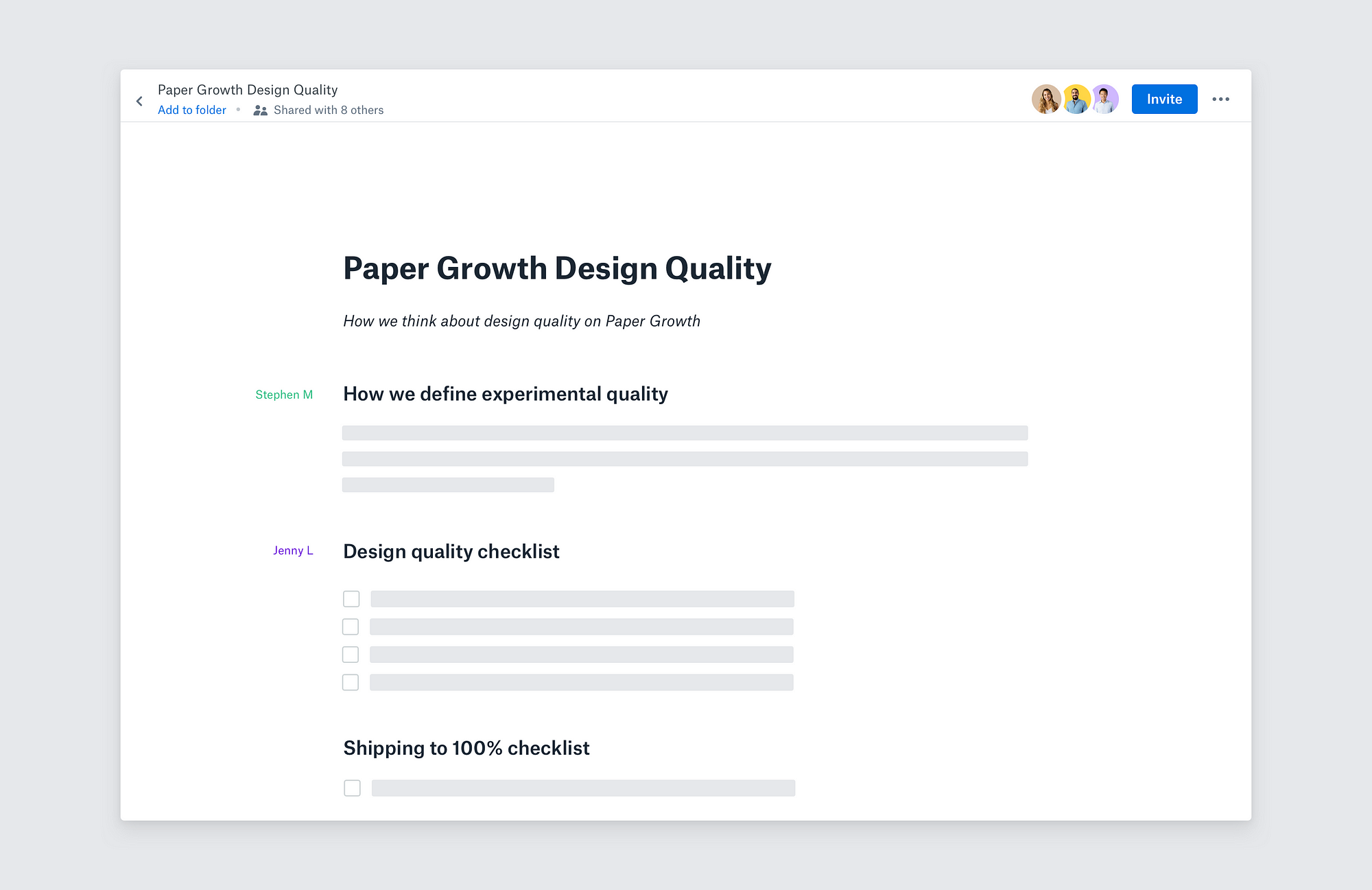

On Paper, we realized that if we wanted to learn from our users through experimentation, we needed to speed up our iteration cycles. Since we wanted to move fast, but also ship great experiences, that raised the question of how much polish we should put in each experiment. To answer that, we decided that instead of the MVP — the minimally viable product, we wanted to build the MPP — the minimally proud product. That means that we try to move as fast as possible to ship; but, when we launch something, we want to be able to answer with “Yes!” to two questions:

- Am I, as a growth designer, proud of the user experience that was shipped?

- On the engineering side: is the engineer proud of what she/he shipped?

Since there’s obvious subjectivity in what makes one proud, we also decided on some objective things that are needed to ship an experiment — a set of shared principles for experimental quality. We all agree that experiments don’t have to be 100% polished. But they should be an experience that with a little bit more polish would be something ready to ship to all users.

Experiments should be good enough to test our hypotheses and learn, and almost good enough to ship to everyone.

2. Don’t break things… or break as little things as possible

When you move fast, things will inevitably break. On the Paper growth team, we try to fix them as soon as possible.

We all acknowledge that in most cases we made tradeoffs, to move fast and ship the experiment to a subset of our users. So, when an experiment is successful, we set aside time to fix bugs and polish the user experience, before we turn it on to 100%.

Even when we set aside time to fix things, it’s likely we’ll omit or overlook bugs or inconsistencies. That’s why we also setup time to periodically audit surfaces where we run a lot of experiments. We all get in a room — engineers, product managers, writers, designers, researchers — and we try out and stress test our own product. This allows us to make sure that: (1) our experiments don’t collide and, even more, that (2) experiments that we launched on a specific surface make sense together, as an end-to-end user experience.

III. Conclusion

Dealing with growth in anything, anywhere, is hard. When you’ve set out to grow a product you really love, it can be both incredibly exhilarating, when it works, and deeply challenging, when it doesn’t.

That’s why developing a great team to take on this challenge is super important. We think that cultivating close relationships with the people you work with and increasing your learning speed are two key ingredients for that. And, as a true growth team, we’ve tried and tested hypotheses on how we work, and tweaked our processes until we got to where we are today.

If anything is certain, it’s that we’ll build on top of what we know today, to challenge and change our processes in search of better ones. If you have any ideas about how to empower growth teams to perform well, reach out! We’d love to hear your thoughts!

Thanks to Justin Tran for the illustration, John Saito and Angela Gorden for feedback, and everyone on the Dropbox Paper growth team for input for this article.

Want more from the Dropbox Design team? Follow our publication, Twitter, and Dribbble. Want to make magic together? We’re hiring!