Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History

Five Points and Whittier are adjoining Denver neighborhoods, and the first to extend beyond the bounds of Denver’s original Congressional Grant. Each neighborhood was created and initially shaped during a long period of growth from the early 1870s to the silver crash of 1893, a time when Denver was amongst the fastest growing cities in the United States and exemplified what the historian Gunter Barth describes as the “instant city.” Each has seen its fortunes wax and wane over a near one-and-a-half century history, and, in that time, has been home to numerous Denver communities, a connection recalled and honored long after people had dispersed.

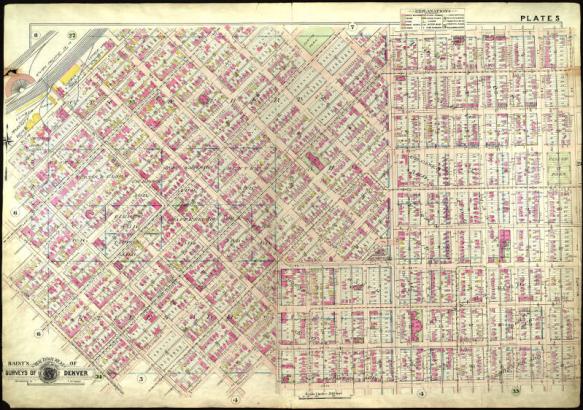

Five Points found its name in reference to the offset conjunction of Denver’s diagonal downtown grid with a rectangular suburban grid, which meet at Washington Street, 27th Street, 26th Avenue, and Welton Street. The Stout Street Herdic Coach Line popularized “Five Points” as the neighborhood’s designation in the early 1880s, but not everyone was pleased with the name. For some it brought to mind the eponymous New York City neighborhood, the most notorious slum in nineteenth-century America. Alternatives, including Welton Center, never made a sufficient impression to displace it. Whittier, a rectangular neighborhood that adjoins Five Points on its eastern edge, found its name in Whittier Elementary School, which honors the nineteenth-century American poet and abolitionist, John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892).

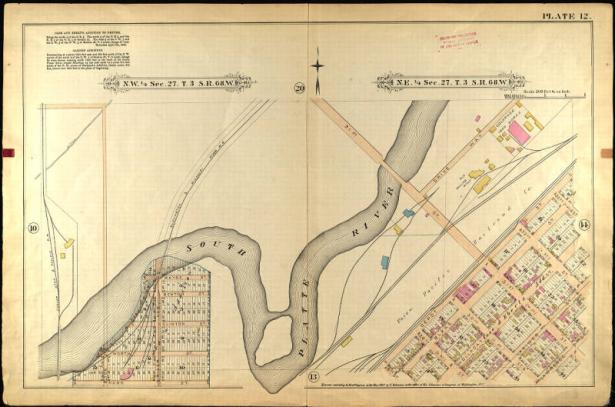

In the late 1860s, Denver was enlarged with the addition of some 1600 acres and eight new subdivisions, three later within the bounds of Five Points (i.e., Case and Ebert’s [1868]; Curtis and Clark’s [1868]; and Shaffenburg’s [1869]). Similarly, Whittier’s major subdivisions were all platted from the late 1860s through the 1870s, a process begun in 1868 with Case’s Addition. Transportation to these new neighborhoods was facilitated with the construction of urban railroads, and the city’s first street railroad, the Denver Horse Railroad Company, connected Five Points with downtown Denver in 1871. As the historian William Allen West observes, the symbolism was unmistakable: with urban railroads and streetcars, Denver was not only of a sufficient size to warrant a transportation system, but also of a permanence to warrant the requisite investment. By August 1879, the Rocky Mountain News had started describing active building and development as Denver extended north and east along the South Platte River.

In its earliest incarnation, Five Points was a mix of residential structures – some grand and stylish, others more modest – and business and industrial concerns. In time, the neighborhood would be home to such businesses as Kuner Pickle, Crescent Flour Mills, Colorado Iron Works, and the Denver Fire Clay Company, and these and other enterprises enjoyed ready access to the South Platte River and the Denver’s rail yard. Curtis Park became Denver’s first public park when a slightly less than two-and-a-half acre parcel, named for Samuel Curtis, was established in 1868. Whittier became home to Denver’s second public park, Fuller Park, with a donation by its namesake, Horace Fuller, in 1879. In contrast to the mixed use for land in Five Points, Whittier was almost entirely residential from its inception, with its most significant commercial or business enterprises found in two-story brick corner stores and shops.

The rapid development of Five Points and Whittier soon saw the establishment of the institutions that gave shape to each neighborhood’s character and community, including churches and synagogues, schools, hotels, restaurants, and drugstores, and other amenities and meeting places.

Zion Baptist Church, originally established in 1865 and Colorado’s oldest African American congregation, first met for worship in a log structure located at the intersection of 20th and Arapahoe streets.

Temple Emanuel, established in 1873, constructed its synagogue at Curtis and 24th Street in 1882, before removing to 16th and Pearl in 1899.

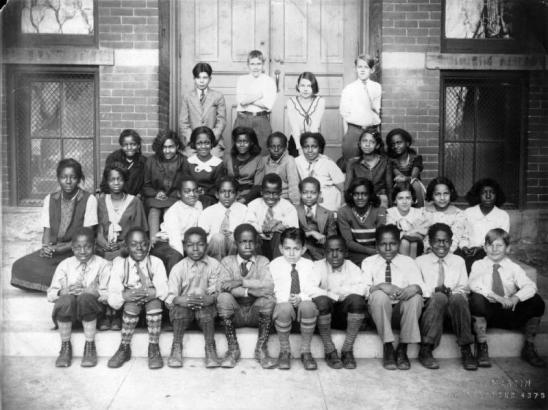

Manual High School, established in Whittier in 1894, became a central public facility for the neighborhoods, and a beloved institution for many residents long after they had departed once familiar streets.

Denver’s continued growth altered the fortunes of the city’s neighborhoods, and with it the communities of Five Points and Whittier. As Denver continued to grow, and new modes of transportation made it possible to reside at a still greater remove from places of employment and commerce, new neighborhoods were established farther from the city’s center. Five Points changed as those with wealth, aspiration, or affectation moved to other neighborhoods that had become fashionable and desirable for residences. As soon as the early 1890s, directories of Denver’s socially prominent placed a majority of residences in Capitol Hill; by the end of the same decade, almost all of the city’s elite resided there. More modest homes were built in Five Points after the economic panic of the 1890s. Such movements would occur again and again in each neighborhood’s history, and each time alter the nature of Five Points and Whittier.

Five Points had long been home to African Americans, but it was in the first few decades of the twentieth century that Five Points became the seat of Denver’s African American community. By the 1870s, African American railroad workers from Georgia had established themselves and their families on 22nd Street, a precinct known as “Deep South.” An analysis of residential patterns during the early 1890s demonstrates that a majority of Denver’s African Americans resided within the bound of Five Points. By the 1920s, more than ninety percent of Denver’s African Americans lived within the bounds of Five Points and the adjacent Whittier neighborhood. As historians Tom and Laurie Simmons observe, by the end of the same decade “black residents of Denver were confined by custom, covenant, and coercion to a fairly concentrated residential area around the Five Points intersection, in an area roughly bounded by Thirty-third Street and East Thirty-third Avenue on the north, High Street on the east, East Twentieth Avenue on the south, and Twentieth and Larimer streets on the West.”

Holly Wasinger has identified the hostile climate of the early twentieth century, symbolized and sustained by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the political life of the city of Denver and the state of Colorado, as the pivotal moment in the creation of Denver’s African American community. In 1915, Denver’s branch of the just established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was created, with George W. Gross as its first president; a little more than a decade later in 1925, the city would be host to a national meeting of the NAACP. Dr. Clarence Holmes Jr., a Denver native lately returned from his study of dentistry at Howard University in Washington, D.C., also played a role in the founding of Denver’s NAACP, and remained deeply involved in other Denver organizations seeking to redress inequality and discrimination throughout his life. Segregation and inequality also reached into the neighborhood schools, including Morey Junior High School and Manual High School, where in 1927 a group of African American students and their parents successfully sued Jessie H. Newlon, Superintendent of Public Instruction of the City and County of Denver, for establishing a separation of social functions for students based on race, contrary to the Colorado constitution.

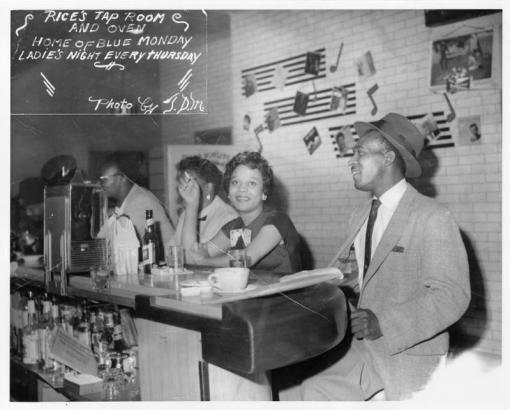

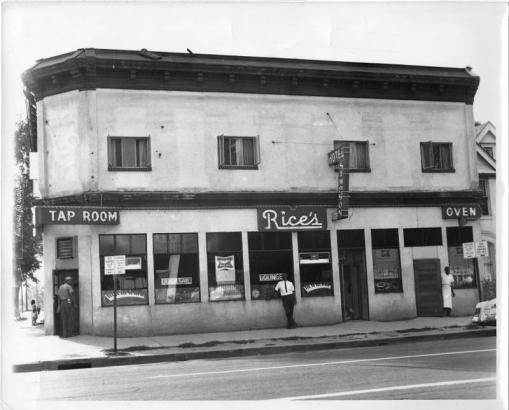

Through the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, Five Points continued as the seat of Denver’s African American community. The period was also the height of the neighborhood’s reign as a cultural and entertainment destination, with local nightspots host to jazz and blues musicians of the day. Businesses, such as the American Woodmen’s Insurance Company, the Rossonian Hotel, and Rice’s Tap Room and Oven flourished, while other neighborhood institutions, like the Phyllis Wheatley Colored YWCA and the Glenarm YMCA, served a community bound, but not defined by, segregation. The Glenarm YMCA, built in 1924 at 2800 Glenarm, has been described as the unofficial town hall of Five Points, and “included a swimming pool, gymnasium, locker rooms, clubrooms, a branch of the Denver Public Library, and dormitories.”

Yet Five Points and Whittier were never simply black neighborhoods, and others found a home, or even a haven, within its bounds. Mexican and Mexican American workers, many seasonally employed in agriculture on the Western Slope or year-round in the city’s brickyards, had established themselves in Five Points in the early twentieth century in neighborhoods around 38th Avenue and Fox Street, along the Platte River and the Burlington tracks, and Sand Street. By the time Curtis Park began its revitalization in the 1980s, some Hispanic residents were the third generation to reside in the Five Points neighborhood. Japanese American residents established themselves in the neighborhood before the entry of the United States into World War II, and during the war years the neighborhood became a home to Japanese Americans who found an alternative to internment in Denver and Colorado. For many Japanese Americans, a stay at the Burlington Hotel at 22nd and Larimer streets was a first stop in Five Points.

Ironically, the slow, bitter end to the segregation of Denver’s neighborhoods forever altered Five Points as the seat of the city’s African American community. With the opportunity to acquire homes in other neighborhoods, most notably the immediately adjacent precincts of Park Hill, residents began to move. And with that movement, the populations of Five Points and Whittier went into precipitous decline. In 1959, the population of Five Points was 32,000; by 1974, it had declined to 8,700. Similarly, Whittier’s population was more than halved between 1950 and 1990, declining from 9,160 to 4,350 people.

In a pattern repeated in other American cities, this decline was met with a succession of efforts to resurrect both the neighborhood and community. Nevertheless, revitalization brought its own challenges, and raised questions about the future character of these neighborhoods and making changes sensitive to their histories. Revitalization brought the prospect of gentrification, with its potential displacement of long-time residents of limited resources by affluent newcomers. Some in the Five Points community opposed plans to extend a new urban rail line to the neighborhood, eventually opened in 1994, seeing it as an effort to divide the community and alter the character of Welton Street. Others remained ambivalent about the prospect of return. In 2005, 81-year-old John Porter reflected on the efforts of previous decades to resurrect his former neighborhood: “When they tried to revive Five Points, people felt like, ‘I spent all this effort to get out of Five Points, why would I want to go back?'” Porter, a 40-year resident of Park Hill, concluded: “That’s how I felt.” Nevertheless, revitalization continued apace, including the 1990s renovation of the Rossonian Hotel, which dominates the Five Points intersection.

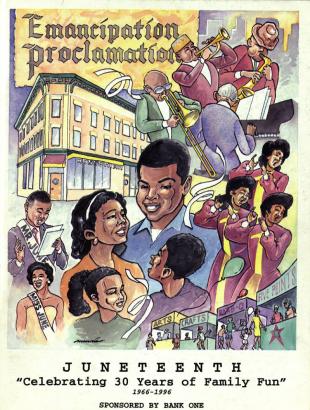

By the early twenty-first century, Five Points had undergone dramatic demographic changes. With the 2000 census, non-Hispanic whites represented 27% of the neighborhood’s population (up from 20% in 1990), blacks 26% (down from 39% in 1990), and Latinos 43% (up from 41% in 1990) of the Five Points community. Familiar businesses, such as Charlene’s House of Beauty, Kapre Chicken, and others closed, perhaps as much a result of passing generations as neighborhood change. Nevertheless, many African Americans continued to regard the Five Points neighborhood as home and to frequent its social, cultural, and religious institutions. In 2003, Reverend Frank Davis of Zion Baptist Church noted that his congregation numbered some 1800, but he estimated that fewer than 10 percent of his congregants resided in Five Points. Students at Manual High School in Whittier were a reflection of change, and their halting, and sometimes uneasy, conversations about race and changes to their neighborhood reflected the tensions of such transformations. Conversely, events on the neighborhood’s cultural calendar such as Juneteenth, a commemoration of emancipation in Texas on June 19, 1865, first organized and celebrated in Denver in 1953 through the efforts of Otha Rice, himself a transplant from Texas and proprietor of Rice’s Tap Room and Oven, also became a common celebration for a diverse community. In 2005, Jeff Fard, a community activist, noted how Five Points served as a source of renewal for a larger black community: “This is where you come to get fuel as an African American.” But Fard also acknowledged and celebrated the neighborhood’s diversity: “This community captures that multiethnic feeling. I have a love affair with Five Points. It’s what we call home.”

The Five Points and Whittier neighborhoods of Denver are located North of Downtown. The Five Points neighborhood when seen on a map does in fact appear to have five distinct points.

However, the neighborhood’s name is derived to the intersections of five different streets in the middle of the neighborhood. Starting at 17th and Downing on the east edge, the Five Points neighborhood extends north along Downing to 38th Street. The boundary continues in the northwest direction from the corner of 38th and Ringsby Court to 20th Street. At the corner of Ringsby and 20th the boundary continues southeast on 20th until it intersects Washington, at which point the boundary continues in a southeast direction until returning to the 10th and Downing intersection.

Not as extensive as the Five Points neighborhood, the Whittier neighborhood is located on the east side of Five Points. This neighborhood starts at 23rd and Downing Streets, runs east until North York Street, goes north until East Martin King, Jr. Boulevard, and runs west until it intersects with Downing, where going south it ends again at the corners of 23rd and Downing.

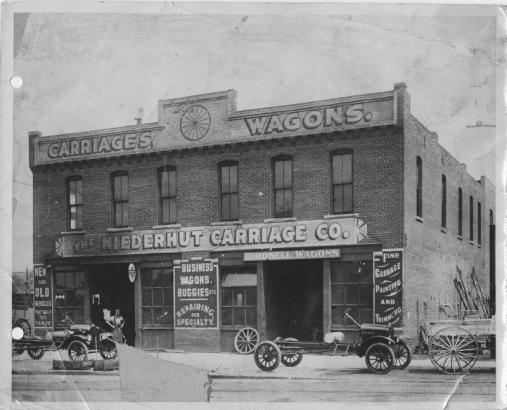

The Niederhut Carriage Company was a family run business in the Five Points Neighborhood of Denver for almost one hundred years. It is debatable when the company was originally founded. Some accounts mention 1883 and others mentions 1895. Whichever the case, brothers Henry E. and William G. Niederhut founded the company. Both brothers were born and educated in Germany and migrated to the United States not long after finishing their education there.

Upon coming to Denver the brothers worked several odd jobs and eventually started shoeing horses and making carriages and wagons for their new company, Niederhut Bros. Over time the company’s name was changed to East Denver Carriage Company in 1896 and then to the Niederhut Carriage Company in 1902. Along with name changes, the services of the company evolved as well. The company effortlessly transitioned from horse drawn vehicles during the turn of the 20th century, to automobile manufacturing in the 1920s, and eventually to creating custom truck bodies for local businesses.

Being one of the largest transportation manufacturing companies in Denver in the early 20th century, a major calamity occurred around 1964 when a fire broke out, destroying many of the business records. Not long after, the Niederhut Carriage Company closed its doors in 1972.

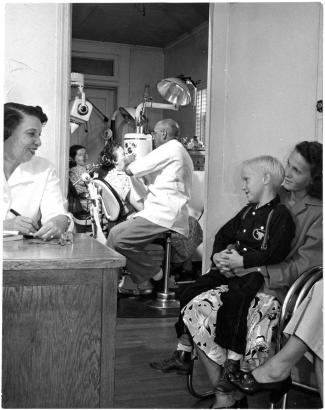

Clarence Fitzhugh Holmes was born May 21, 1892 in Denver, Colorado, after his parents moved from Washington D.C. Clarence and his older brother William grew up at 2139 Curtis Street. He attended Ebert School and graduated from Manual High School in Denver in 1913, and Howard University and Howard University College of Dentistry in Washington D.C. (B.S. 1917, D.D.S. 1920). Clarence Holmes married Fairfax Butler Richey on April 2, 1923 in Denver. They moved briefly to Pueblo, Colorado in 1926, but returned to Denver in 1931.

In 1920, Clarence Holmes opened a dental practice at 2602 Welton Street in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood. While not the first licensed African American dentist in Colorado, a distinction that belongs to Dr. Ernest McClain (licensed in 1907; practiced until 1948), Holmes was the first African American dentist to join the Denver Dental Society. In later years, Holmes recalled some initial opposition to his membership, most notably a fear he might attend a dance. He wryly observed that his wife did not dance, and he had no intention of joining a dance club. During the Depression, he performed free extractions for people as part of a Community Chest program. Holmes retired from his dental practice in 1975.

Clarence Holmes helped to found the Colorado-Wyoming branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a group he joined while at Howard University. He also helped to found the Glenarm YMCA, which unlike other Denver YMCA branches was open to African Americans. Holmes was perhaps best known for his involvement with community organizations in Denver such as the Cosmopolitan Club, an organization comprised of socially progressive men and women who believed in promoting interracial and interfaith understanding. Holmes founded the club in 1931 and served as its president for over 30 years. Clarence Holmes and his wife, Fairfax, were also members of St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral.

Holmes participated in various philanthropic organizations such as the Cosmopolitan Club, Denver Chi Phi chapter of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, the Red Cross and the Salvation Army. Despite his passionate involvement in clubs, social organization, and his fraternity, Holmes had no patience for exclusivity, and once humorously derided the country club set as “a bunch of crumbs held together by their dough.” He also served on the Colorado Commission for the Aging, and on the Mayor’s Committee on Community Relations under Mayor Quigg Newton. Holmes received numerous community awards and recognitions including the Mile-Hi Sertoma Club “Outstanding Citizen” award in 1973 and the Brotherhood Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews in 1974. In 1955, Holmes lost a bid for City Council to Elvin Caldwell.

Clarence Holmes died in a Denver nursing home on March 9, 1978. Fairfax Holmes died in June 1980. They are buried with their daughter, June, at Fairmount Cemetery.

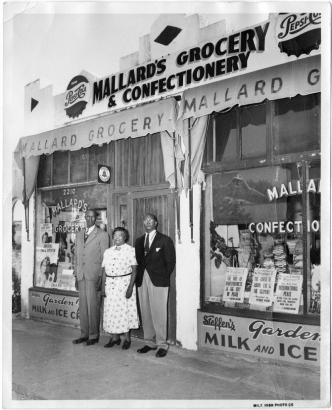

Reverend David West Mallard was born on March 21, 1887 in Rusk Cherokee County, Texas. He was a Pullman porter from August 1909 to July 1921 until he retired on disability. He was member of the Sleeping Car Porters.

After his retirement he became a Five Points entrepreneur, owning several business including a restaurant at 2628 Welton (1935), a cleaning business, and a grocery store and confectionery. Mallard’s Grocery and Confectionery opened in 1933 and was located on 22nd and Downing Street. Reverend Mallard also worked at the Midland Hotel at 17th and Arapahoe (1938), and at the Mine and Smelter Supply Company at 1422 17th Street (1937-1938). He was a member of Campbell Chapel African American Episcopal Church (A.M.E) for 53 years and was the assistant pastor. He passed away in Denver in January of 1978. His wife Virginia “Pinky,” followed him in death five days later.

Otha P. Rice, Sr. (1916-1993) was a native of Texas, and moved with his family to Chicago during childhood. He moved to Denver as a young man, where he married Irene Hazel Johnson and had four children. Otha became a beloved figure in the Five Points neighborhood of Denver, Colorado, where he was very active in civic organizations and neighborhood issues. Otha was well known, along with “Big Al” Richardson for bringing the Juneteenth celebration to Denver in the early 1950s. Otha was a 1934 graduate of Denver Manual High School, worked as a porter on the railroad, was a postal service mail carrier, and eventually became owner of Rice’s Tap Room and Oven in Five Points on 28th and Welton Streets.

The two-story Tap Room included a jazz and blues club, a bar and a restaurant on the first floor and the Simmons Hotel on the second floor. The club featured live jazz and blues every week on “Blue Monday” and every Thursday was the ever-popular “Ladies Night.” The Tap Room provided the citizens of Five Points the opportunity to relax and enjoy a wide variety of entertainment, and it was a very popular and important business in the Five Points neighborhood.

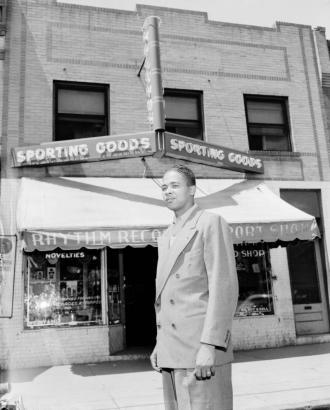

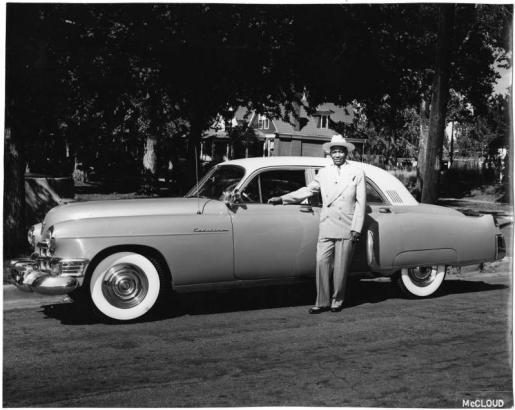

Leroy was born in Poteau, Oklahoma on July 11, 1911 and died in 1989 at the age of 77. A well-known figure in the Five Points neighborhood and the city of Denver, Leroy always strived to make his mark on society and was successful in that endeavor. After working as a young man in the cotton fields and then as a railroad Pullman Porter, Leroy settled in Denver and started The Rhythm Records Shop in 1939.

Leroy became interested in music while in Chicago which led to the opening and success of his store in the Five Points neighborhood. Leroy also had an interest in firearms and became the first African American to obtain a license to sell firearms in Colorado. He changed the name of his store to The Rhythm Records and Sporting Goods Shop as a result and it became a very successful business venture.

Leroy married Lula A. Green and raised five children. Later in life he became friends with the entertainment promoter Bill Jones and became his apprentice. He later ventured out on his own as a promoter of various bands and entertainers such as James Brown, Nat King Cole, Count Basie, Fats Domino, Lou Rawls and many other famous black entertainers and acts. He leased out the Rainbow Ballroom for 10 years for various shows and also rented out his business apartments for entertainers such as Billy Holiday during their engagements in Denver. He was also a friend of Cassius Clay, now known as Muhammad Ali.

Leroy was very active in the Five Points scene and was considered a neighborhood activist. His Rhythm Records Shop took part in many African American beauty contests by sponsoring Miss Rhythm Records and Sporting Goods beauty contestants, which were very popular in the neighborhood. As a successful businessman with The Rhythm Records and Sporting Goods Shop and other business endeavors such as the Five Points Uranium Company, he carried weight and prominence in the neighborhood. His achievements were many. He started the Colorado Negro Voters Club in the 1960s. He was the first black disc jockey on Denver’s KIMN and KFEL radio in 1948. His love of firearms and the outdoors led to his becoming a Special Game Warden in 1958. Not only was he the owner of the Rhythm Records shop, but he also became owner of the Rainbow Ballroom. For 20 years he was the Organizer of the Wild Game Feast of Colorado. He was a member of the Five Points Businessmen Association and a 33rd degree Mason of the Shriners of Syrian Temple No.49. In addition he was the first black member of the Chamber of Commerce, the first black branch president of Ducks Unlimited in Colorado and a candidate for City Councilman of District 8 in 1955. He was also one of the organizers of the Five Points Juneteenth Celebrations. A crowing achievement was an Honorary Citation by Governor Roy Romer honoring his many years of service to the Black Community.

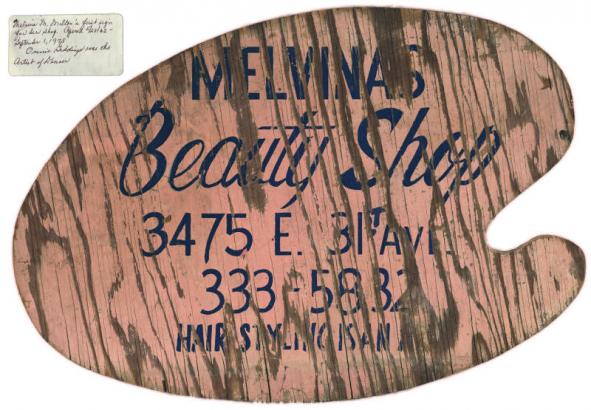

Melvina M. Williams was the owner of Melvina’s Beauty Shop at 3475 E. 31st Avenue. She worked in three beauty shops in the Five Points area. She married Reverend Chester Williams and has four daughters, three grand children, one great granddaughter, one great grandson and two great great grandsons. She lives in Topeka, Kansas and is a writer and genealogist.

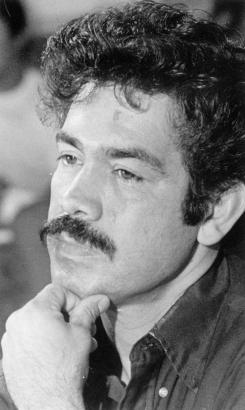

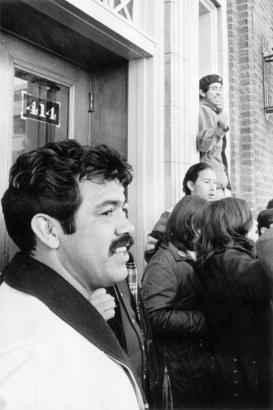

Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales was born on June 18,1928 at Denver General Hospital in Denver, Colorado. His father, Federico Gonzales, was from Buena Ventura, Chihuahua, Mexico. His mother, Indalesia Lucero, was born in Colorado on June 30,1889. Corky Gonzales was the youngest of four brothers, one half-brother and three half-sisters. His mother died when he was two years old. He attended public elementary schools in Denver, and briefly in New Mexico. From the time he was ten years old, he worked in his spare time as a farm hand, a pin setter in bowling alleys and a hide gang laborer. Gonzales graduated from Manual High School in 1944 when he was 16 years old. He attended the University of Denver briefly, but the tuition became more than he could afford.

In 1944, Gonzales became an amateur boxer, fighting first at a Veteran’s Athletic Club Smoker. While he belonged to the Epworth Boxing Club in Denver, he won both the Golden Gloves and Diamond Gloves Tournaments. In 1946, Gonzales was the Colorado Regional Amateur Flyweight Champion and in 1947 he was the National Amateur Athletic Union Bantamweight Champion.

Turning professional in 1947, Gonzales fought 75 times as a featherweight. During his professional fight career, he made his home for awhile in Omaha, Nebraska and St. Paul, Minnesota. He fought the best fighters of his day including Willie Pep, Charley Riley, Gene Smith, The Flanagan brothers, Harold Dade, Lulu Perez, and others. His last professional bout was for a 1952 benefit bout in Denver for the Latin American Education Fund. Overall, Gonzales’ professional record was 65-9-1. The National Boxing Association and Ring Magazine had him rated as high as the number three featherweight in the world.

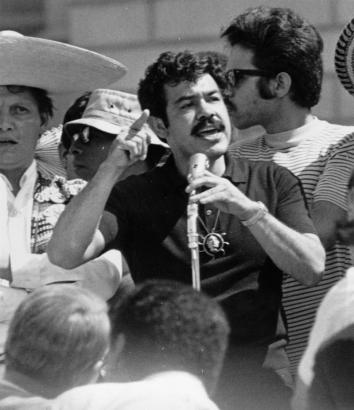

After boxing, Gonzales opened what was arguably Denver’s first sports bar: Corky’s Corner on the corner of 38th and Walnut Street. Later on Corky sold his tavern and embarked on a new business: Corky’s Bail Bonds in Denver. He also became a general agent for Summit Fidelity and Surety Company of Colorado in 1963. In 1965, Mayor Thomas Currigan appointed Gonzales as Director of Denver Neighborhood Youth Corps. Gonzales also acted as the Director of the War on Poverty. In 1966, Gonzales objected to a Rocky Mountain News story he felt was libelous toward him in particular and the Mexican American community in general. He was visibly angry in a news conference and led a protest at the newspaper building. Objecting to these behaviors, Currigan fired him from his Youth Corps position. Gonzales resigned his position as Director of the War on Poverty soon afterward. Gonzales was quoted as saying, “I’m an agitator and a trouble maker. That’s my reputation and that’s what I’m going to be. They didn’t buy me when they put me into this job.”

The first time Gonzales ran for political office was in 1955 in an unsuccessful bid for the Five Points City Council position that Elvin Caldwell eventually won. In 1960 he campaigned for John F. Kennedy, coordinating the “Viva Kennedy” campaign in Colorado. In this campaign, Gonzales registered more Mexican Americans than at any other time in Colorado’s political history allowing Kennedy to carry the State of Colorado. During this time, he was also serving as Colorado’s first Mexican American democratic District Captain. At the same time, he made an unsuccessful bid for State Representative in the Colorado Legislature. His final political effort was in 1967 when he ran for Denver mayor against Thomas Currigan. Again defeated, Gonzales sued Currigan for violating an old Denver campaign law.

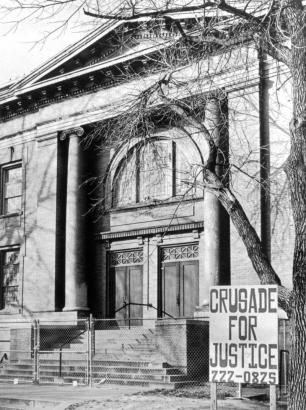

In 1965, due to a complete and unbroken history of racism, bigotry and discrimination practiced by the dominant society against Mexican Americans in Denver, Colorado and the Southwest United States, Gonzales founded Crusade for Justice as a social movement to empower the Chicano population. In 1969, Gonzales opened a summer Liberation School, and in 1970, the Escuela Tlatelolco was born as a school for Chicano children. The Ballet Chicano de Aztlan, a Chicano dance troupe, and El Teatro Pachuco was a part of Escuela Tlatelolco and was made up of elementary, middle, and secondary school students. The Crusade for Justice building was at 1567 Downing Street.

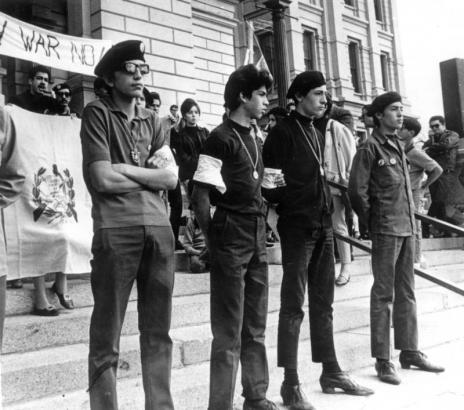

Besides his writings, Gonzales was perhaps best known for his leadership and involvement in the Chicano Movement. He organized and led protests as well as spoke at rallies and university campuses throughout the country. In 1968, he led a Chicano contingent in the Poor People’s March on Washington. In 1969, after racist remarks by a teacher, West High School students approached Gonzales to help the students by hosting meetings with adults, parents and students. The Crusade also provided support and guidance to student organizers who inspired the walkout at West High School. The Chicano Youth Conference of 1969 led to the writing of El Plan de Aztlan, a document that articulated Chicano political, social, economic, and educational issues and demands.

Violence was at times associated with Crusade activities. In March 1973, the police provoked shootings between the Denver Police and Crusade members which led to the bombing of an apartment building owned by the Crusade for Justice and adjacent to the Crusade building. Luis Junior Martinez, a young teacher and dance director of the Crusade, was gunned down by police. In 1981, La Raza Park (otherwise known as Columbus Park) in Northwest Denver was cleared of people by Denver police during summer festivity event. In 1971, Gonzales was arrested at an anti-war rally in Los Angeles. He was convicted of allegedly carrying a loaded weapon and served four months in jail.

Gonzales married Geraldine Romero, born in Brighton, Colorado in 1931, in 1949. They had eight children, six daughters and two sons. Gonzales died on April 12, 2005 of congestive heart failure. He was 76 years old. He is aptly remembered as “the fist” of the Chicano Movement. In 2009, the 3rd Annual Corky Gonzales Symposium: 40 Years of Activism in Denver took place in the Tivoli Student Union at the Auraria Campus in Downtown Denver.

His legacy is multifold: he is honored as a founder of Chicano literature, a creator and promulgator of today’s Hispanic cultural identity, and a voice against inequality in all forms. His efforts to fight police violence, to end poverty, and to stop educational discrimination were the precursors to contemporary struggles in the same arenas. As the website for the Rodolfo ‘Corky’ Gonzales Annual Symposium notes, “Even today, Chicanos are confronted with the same issues that were raised in 1969: voting rights, immigration, institutional racism in the criminal and juvenile justice systems, racial profiling, health care reform, and the list goes on…

He believed the key to liberation for the Chicano community is to develop a strong power base with heavy reliance on nationalism among Chicanos. His contributions as a community organizer, youth leader, political activist, and civil rights advocate have helped to create a new spirit of Chicano unity.”

Learn more on our Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales Exhibit page.

Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration of the ending of slavery in the United States. On September 22, 1862, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued by Abraham Lincoln declaring that that in January 1863 all persons held in slavery within any state would forever be set free. On June 19th, 1865, two and a half years after the proclamation, the news reached Galveston, Texas, where slavery was still practiced. The news of this historic document was greeted with celebration and joy.

Otha P. Rice, a native of Texas, brought the Juneteenth celebration to 28th and Welton Streets in the Five Point Neighborhood in the early 1950s. In 1966, Al Richardson, also a native of Texas, picked up the celebration for the Five Points Business Association (FPBA) and the community. Thereafter, the FPBA has held a colorful annual 4-day family oriented festival and celebration in honor of the historic document delivered at Galveston, Texas in June of 1865.

The celebration is important to Denver’s African American community because it is a time for community members to celebrate and connect with each other, as well as to become educated about the purpose of the celebration. It is also a time to express pride in the history and culture of the Five Points neighborhood. Vendor booths, ethnic foods and a parade are also part of the Juneteenth celebration. The Juneteenth celebration has ebbed and flowed over the years, but organizer efforts to improve the Five Points area, as well as the community’s support, has brought the Five Points neighborhood and its citizens together to help celebrate common interests.