I built a Progressive Web App and published it in 3 app stores. Here’s what I learned.

One month of work, several hundred dollars, and lots of red tape.

I recently published Chavah Messianic Radio, a Pandora-like music player, as a Progressive Web App and submitted it to the 3 app stores (Google Play, iOS App Store, Windows Store).

The process was both painful and enlightening. Here’s what I learned.

Why?

First, you might wonder, “Why even put your app in the app stores? Just live on the opened web!”

The answer, in a nutshell, is because that’s where the users are. We’ve trained a generation of users to find apps in proprietary app stores, not on the free and open web.

For my web app, there were 2 big reasons to get in the app store:

- User demand

- Web app restrictions by Apple hostile mobile platforms

User demand: My users have been asking me for years, “Is there an app for Chavah? I don’t see it in the store.”

They ask that because we’ve trained users to look for apps in proprietary app stores.

My response to my users has up until now been,

“Aww, you don’t need an app — just go to the website on your phone! It works!”

But I was kind of lying.

Real web apps only kinda-sorta work on mobile. Which brings me to the 2nd reason: web app restrictions by Apple hostile mobile platforms.

Mobile platform vendors, like Apple, are totally cool with apps that use your phone to its fullest. Access your location, play background audio, get your GPS coordinates, play more than one thing at a time, and more.

Apple’s totally cool with that.

But only if you pay Apple $99/year for the privilege.

If you want to do any of those things in a regular old web app, well, goshdarnit, Apple won’t just deny you these things, it prevents you from even asking permission.

For my Pandora-like music player app, this horrible brokenness showed up in numerous ways.

From minor things like “iOS Safari won’t let you play audio without first interacting with the page” to major, show-stopping things like, “iOS Safari won’t let you play the next song if your app is in the background or if your screen is off.”

Oh, plus weird visual anomalies like typing in a textbox and seeing your text appear elsewhere on screen.

So, to make my HTML5 music app actually functional and working on people’s mobile devices, it was necessary to turn my PWA into an app in app store.

Barriers to entry

In the ideal world, publishing your web app to the app stores would look like this:

- Your Web/Cloud Host or Continuous Integration Provider

- You’ve published a Progressive Web App. Publish to app stores?

☑ iOS App Store

☑ Google Play

☑ Windows Store

(Or alternately, as Microsoft is experimenting with, your PWA will just automatically appear in the app store as Bing crawls it.)

But alas, we don’t live in this ideal world. Instead, we have to deal with all kinds of proprietary native BS to get our web apps in the stores.

Each of the app stores has a barrier to entry: how difficult it is to take an existing web app and it in the app store.

I list some of the barriers below.

Cost

- Apple: $99/year to have your app listed in the iOS app store.

- Google: One-time $25 fee to list your app in the Google Play Store.

- Microsoft: Free!

Don’t make me pay you to make my app available to your users. My app enriches your platform. Without good apps, your platform will be abandoned.

Apple used to understand this. When it first introduced the iPhone, Steve Jobs was adamant that HTML5 was the future and that apps will simply just be web apps. There was no native iPhone SDK for 3rd parties. Apple has since abandoned this vision.

Google asked for a token $25 one-time fee. Probably to avoid spammers and decrease truly junk apps from entering the store.

Microsoft seems determined to just increase the total number of apps in their app store, regardless of quality.

Winner: Microsoft. It’s hard to beat free.

Adding native capabilities

In an ideal world, I wouldn’t have to write a single extra line of code for my web app to integrate into the OS. Or, as Steve Jobs said back in 2007,

“The full Safari engine is inside of iPhone. And so, you can write amazing Web 2.0 and Ajax apps that look exactly and behave exactly like apps on the iPhone. And these apps can integrate perfectly with iPhone services. They can make a call, they can send an email, they can look up a location on Google Maps.”

-Steve Jobs, 2007

For me, that means my web app plays background audio using standard HTML5 audio; that works just fine on all OSes.

My web app declares what audio is playing, and the OSes pick up on that, show currently playing song info on the lock screen.

My app controls audio using standard HTML5 audio API; the OS picks up on that and provides play/pause/next/volume/trackbar controls on the lock screen.

But sadly, we don’t live in this ideal world. All the things listed above don’t actually work out of the box on all 3 platforms.

My web app needs to play audio in the background. And load URLs from my CDN. Sounds reasonable, right? And bonus, how about showing currently playing song info on the lock screen? And controlling the audio (play/pause/next, etc.) from the lock screen? How hard is this?

Three very different approaches taken here:

- Apple: We don’t give web apps a way to declare such capabilities; you’ll need to write a native wrapper (e.g. with Cordova) to interact with the OS.

- Google: Web FTW! Let’s create a new web standard that shows audio & controls from the lock screen. Background audio? Sure, go ahead!

- Microsoft: We’ll inject our proprietary API, window.Windows.*, into your JavaScript global namespace and you can use that to do the things you want to do.

Going into more details here for each store:

For iOS app store, does your web app need to play background audio? Use a Cordova plugin. Need to show currently playing song on the lock screen? Use a Cordova plugin. Need to control the currently playing song from the lock screen? Use a Cordova plugin. You get the idea. Basically, Cordova tricks Apple into thinking you’re a native app. And since you’re not a yucky web app, Apple lets you do all the things native apps can do. You just need native tricks — Cordova plugins — to let you do it.

For Google Play, it’s nice that I can just write JS code to make this work; no Cordova plugins required here. Of course, that JS won’t work anywhere except Chrome on Android…but hey, maybe one day (in an ideal world!) all the mobile browsers will implement these web APIs…and the world will live as one. I’m almost ready to bust out some John Lennon hippie utopia tunes.

For Windows Store, do you want to play background audio? Sorry! That is, unless you declare your intentions in our proprietary capabilities manifest file (easy) AND you implement this proprietary media interface using window.Windows.SystemMediaTransportControls (not so easy). Otherwise we’ll mute you when your app goes to the background.

Winner: Google. I want to be able to just write JavaScript, and let the OS pick up cues from my app.

Runner-up: Windows. I can still write plain old JavaScript, but I need to talk to a proprietary Windows JS API that was injected into my process when running on Windows. Not terrible.

Loser: Apple. They don’t care about web apps. Actually, it’s worse than that. It feels like they are actually hostile to web apps. iOS Safari is the new Internet Explorer 6. It has lagged behind in nearly every web standard, especially around Progressive Web Apps. This is probably for business reasons: web apps disrupt their $99/year + 33% in-app purchases racket. So to make my web app work on their platform, I have to basically pretend I’m a native app.

App Store Registration

Submitting your PWA to the app store requires registration, business verification, and more red tape. Here’s how the 3 app stores fared:

- Apple: You must prove that you’re a legal, registered business. This verification isn’t done by us — but by a 3rd party, which may or may not know about your business.

- Google: You want your app in our store? Cool by us.

- Microsoft: You want your app in our store? Cool by us.

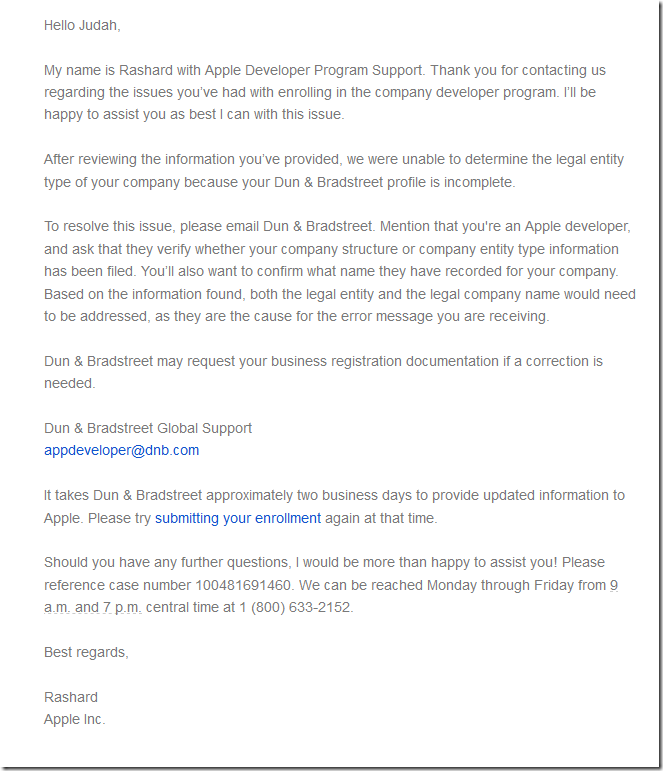

The biggest pain point for me was getting verified as a legal business by Apple.

First, I went to the site and registered for Apple’s Developer Program. I filled out my name and company information. (Aside: I guess Apple won’t let you submit an app unless you have a registered, legal company?)

I click next.

“The information you entered did not match your D&B profile.”

My…what?

A bit of Googling showed that “D&B profile” is Dun and Bradstreet. I’ve never heard of this group before, but I find out that Apple is using them to verify you legal corporation details.

And apparently, my D&B profile didn’t match what I put in my Apple Dev registration.

I google some more and find the Apple dev forums littered with similar posts. Nobody had a good answer.

I contact Apple Dev support. 24 hours later, I’m contacted by email saying that I should contact D&B.

I decide to contact them…but Apple says it will take up to a few days for them to respond.

At this point, I’m thinking of abandoning the whole idea.

While waiting for D&B support to get back to me, I decide to go to the D&B site, verify my identity, and update my company information which, I assume, they had taken from government registration records.

Did I mention how sucky this is? I just want to list my existing web app in the store. Plz help.

I go to D&B to update my business profile. Surprise! They have a JavaScript bug in their validation logic that prevents me from updating my profile.

Thankfully, I’m a proficient developer. I click put a breakpoint in their JavaScript, click submit, change the isValid flag to true, and voila! I’ve updated my D&B profile.

Back to Apple Dev –> let’s try this again. Register my company…

“Error: The information you entered did not match your D&B profile.”

AREYOUFREAKINKIDDINGME.

Talk to Apple again. “Oh, it may take 24–48 hours for the updated D&B information to get into our system.”

You know, because digital information can take 2 days to travel from server A to server B. Sigh.

Two days later, I try to register…finally it works! Now I’m in the Apple Developer program and can submit apps for review.

Winner: Google and Microsoft; both took all of 5 minutes to register.

Loser: The Apple Developer registration was slow and painful. It took about a week to actually get registered with their developer program. It required me contacting support from 2 different freaking companies. And it required me to runtime debug the JavaScript code on a 3rd party website just so that I can get past their buggy client-side validation, so that my info will flow to Apple, so that I can submit my app to the store. Wow, just…wow.

If there is any saving grace here for Apple, it’s that they have a 501c3 non-profit program, where non-profits can have their $99 annual fee waived. I took advantage of that. And perhaps this extra step complicated matters.

App Packaging, Building, Submitting

Once you have a web app, you have to run some magic on it to turn it into something you can submit for App Store review.

- Apple: First, buy a Mac; you can’t build an iOS app without a Mac. Install XCode and these build tools and frameworks, acquire a certificate from our developer program, create a profile on a separate website called iTunes Connect, link it up with the certificate you generated on the Apple Dev center, then submit using XCode. Easy as one, two, three…thirty-seven…

- Google: Download Android Studio, generate a security certificate through it, then package it using the Studio. Upload the package to Android Developer website.

- Microsoft: Generate an .appx package using these free command line tools, or Visual Studio. Upload to the Microsoft Dev Center website.

The good news is, there’s a free tool to do the magic of turning your web app into app packages. That awesome free tool is called PWABuilder. It analyzes a URL, tells you what you need to do (e.g. maybe add some home screen icons to your PWA web manifest). And in a 3 step wizard, it lets you download packages that contain all the magic:

- For Windows, it actually generates the .appx package. You can literally take that and submit it on the Windows Dev Center site.

- For Google, it generates a wrapper Java app that contains your PWA web app. From Android Studio, you build this project, which generates the Android package that can be uploaded to the Android Dev Center site.

- For Apple, it generates an XCode project which can be built with XCode. Which requires a Mac.

Once again, Apple was the most painful of all of these. I don’t have a Mac. But you cannot build the XCode project for your PWA without a Mac.

I don’t want to pay several thousand dollars to publish my free app in Apple’s app store. I don’t want to pay for the privilege of enriching Apple’s iOS platform.

Thankfully, MacInCloud costs about $25/month, and they give you a Mac machine with XCode already installed. You can remote into it using Windows Remote Desktop, or even via a web interface.

It wasn’t enough to just build the XCode project and submit. I had to generate a security certificate on the Apple Developer site, then create a new app profile in a separate site, iTunes Connect, where you actually submit the package.

And that wasn’t all: since Apple is hostile to web apps, I had to install some special frameworks and add Cordova plugins that allow my app to do things like to play audio in the background, add the current song to the lock screen, control the song volume and play status from the lock screen, and more.

This took at least a week of finagling to get my app into a working state before I could submit it to the app store.

Winner: Microsoft. Imagine this: you can go to a website that generates an app package for your web app. And if that’s not your thing, you can download command line tools that will do the job. GUI person? The free Visual Studio will work.

Runner-up: Google. Requires Android Studio, but it’s free, runs everyone, and was simple enough.

Loser: Apple. I shouldn’t have to buy a proprietary computer — a several thousand dollar Mac — in order to build my app. The Apple Dev Center –> iTunes Connect tangling seems like an out-of-touch manager’s attempt to push iTunes onto developers. It should simply be part of Apple Developer Center site.

App Testing

Once you finally did all the magic incantations to turn your existing web app into a mobile app package, you probably want to send it out to testers before releasing your app on the unwashed masses.

- Apple: For testing, you have your testers install Test Flight on their iOS device. Then you add the tester’s email in iTunes Connect. The tester will get a notification and can test your app before it’s available in the app store.

- Google: In Android Dev Center, you add email addresses of testers. Once added, they can see your alpha/beta version in the App Store.

- Microsoft: I didn’t actually use this, so I won’t comment on it.

Winner: Toss up. Apple’s Test Flight app is simple and streamlined. You can control alpha/beta expiration simply on the admin side. Google wasn’t far behind; it was quite painless, not even requiring a separate app.

App Review

Once your app is ready for prime time, you submit your app for review. The review is done using both a programmatic checklist (e.g. do you have a launch icon?) and by real people (“your app is a clone of X, we reject it”)

- Apple: Prior to submission, XCode warns you about potential problems during build. The human app review takes about 24–48 hours.

- Google: Anybody home? Android Studio didn’t tell me about any potential problems, and my app was approved within minutes of submission. I don’t think a real human being looked at my app.

- Microsoft: Upon submission, a fast programmatic review caught an issue pertaining to wrong icon formats. After passing, a human reviewed my app within 4 days.

Winner: Apple.

Sure, as a developer, I like the fact that my app was instantly in the Google Play store. But that’s only because, I suspect, it wasn’t actually reviewed by a human.

Apple had the quickest turnaround time for actual human review. Updates also passed review within 24 hours.

Microsoft was hit or miss here. The initial review took 3 or 4 days. An later update took 24 hours. Then another update, where I added XBox platform, took another 3–4 days.

Conclusion

It’s painful, and costs money, to take an existing PWA and get them functional on mobile platforms and listed in the App Store.

Winner: Google. They made it the easiest to get into the app store. The made it the easiest to integrate into the native platform, by attempting to standardize web APIs that OS platforms can pick up on (hello, lovely navigator.mediaSession)

Runner-up: Microsoft. They made it the easiest to sprinkle your web app with magic, turning it into a package that can be submitted to their store. (Can be done for free using the PWABuilder site!) Integrating with their platform means using the auto-injected window.Windows.* JavaScript namespace. Not bad.

Loser: Apple. Don’t require me to buy a Mac to build an iOS app. Don’t force me to use native wrappers to integrate with your platform. Don’t require me to screw around with security certificates; let your build tools make them for me, and store them automatically in my Dev Center account. Don’t make me use 2 different sites: Apple Dev Center and iTunes Connect.

Final thoughts: The web always wins. It defeated Flash. It killed Silverlight. It destroyed native apps on desktop. The browser is the rich client platform. The OS is merely a browser-launcher and hardware-communicator.

The web will win, too, on mobile. Developers don’t want to build 3 separate apps for the major platforms. Companies don’t want to pay for development of 3 apps.

The answer to all this is the web. We can build rich web apps — Progressive Web Apps — and package them for all the app stores.

Apple in particular has a perverse incentive to stop the progress of the web. It’s the same incentive that Microsoft had in the late ’90s and early 2000s: it wants to be the platform for good apps. PWAs undermine that; they run everywhere.

My software wisdom is this: PWAs will eventually win and overtake native mobile apps. In 5–10 years, native iOS apps will be as common as Win32 C apps. Apple will go kicking and screaming, keeping iOS Safari behind the curve, blocking PWA progress where they can. (Even their recent “support” for PWAs in iOS Safari 11.1 actually cripple PWAs.)

My suggestion to mobile app platforms is embrace the inevitable and either automatically add quality PWAs to your app store, or allow developers to easily (e.g. free, and with 3 clicks or less) submit a PWA to your store.

Readers, I hope this has been helpful glance at PWAs in App Stores in 2018.

Have you submitted a PWA to an app store? I’d love to hear your experience in the comments section. And you can read more of my blog posts on my blog.