Why our engineering leaders focus on product over process

Who was the best manager you ever had?

Even though all of us have different people in mind, those people probably have a lot in common. Maybe he really cared about you as a person. Maybe she was a brilliant visionary who always knew how to push you to be better. Maybe their leadership styles were different — but I’d wager that their philosophies were the same.

I’m sure it’s even easier to recall the worst manager you’ve ever had — the ones who were driven by ego, or who worshipped a process at the expense of the people, or who didn’t have the context to guide you effectively. It’s not always that people themselves are bad leaders; leadership is a skill, and few are talented leaders without working hard at it.

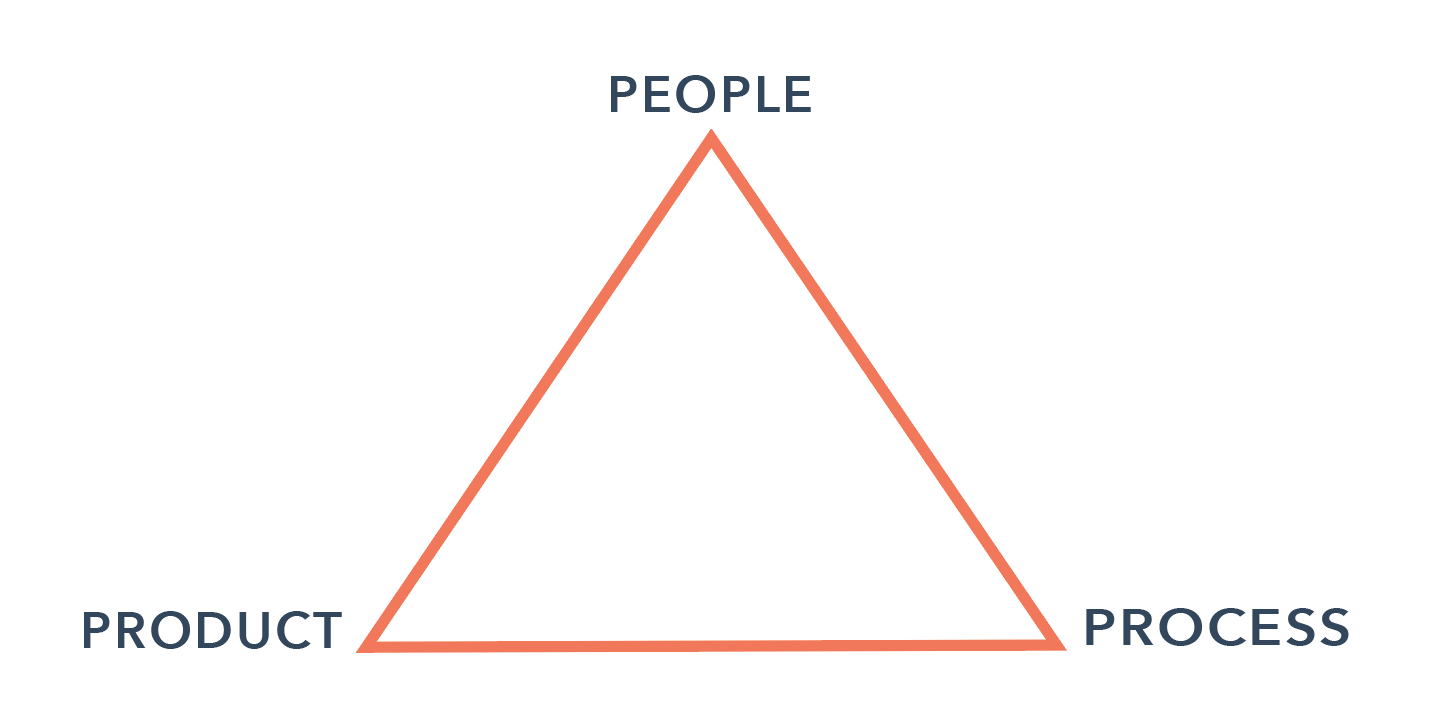

Engineering leadership usually has three things in scope: process, people, and product (that includes technology and architecture). Most leaders can fully focus on only one or two of these; it’s nearly impossible to do all three of them well.

Each area of focus comes with its own pros and cons. Are you spending most of your day in Scrum meetings, or making sure the iterations are going well and teams are hitting their commitments? Are you spending most of your day managing under-performers, or coaching reports in 1:1s and talking about career paths? Or are you spending most of your day trying to ensure that your team is building a great product with a great technical foundation? There’s no correct answer, but your choice leads to very different outcomes and styles of leadership.

Most companies encourage their engineering leaders to focus primarily on process or on people, and their diagrams might look something like this:

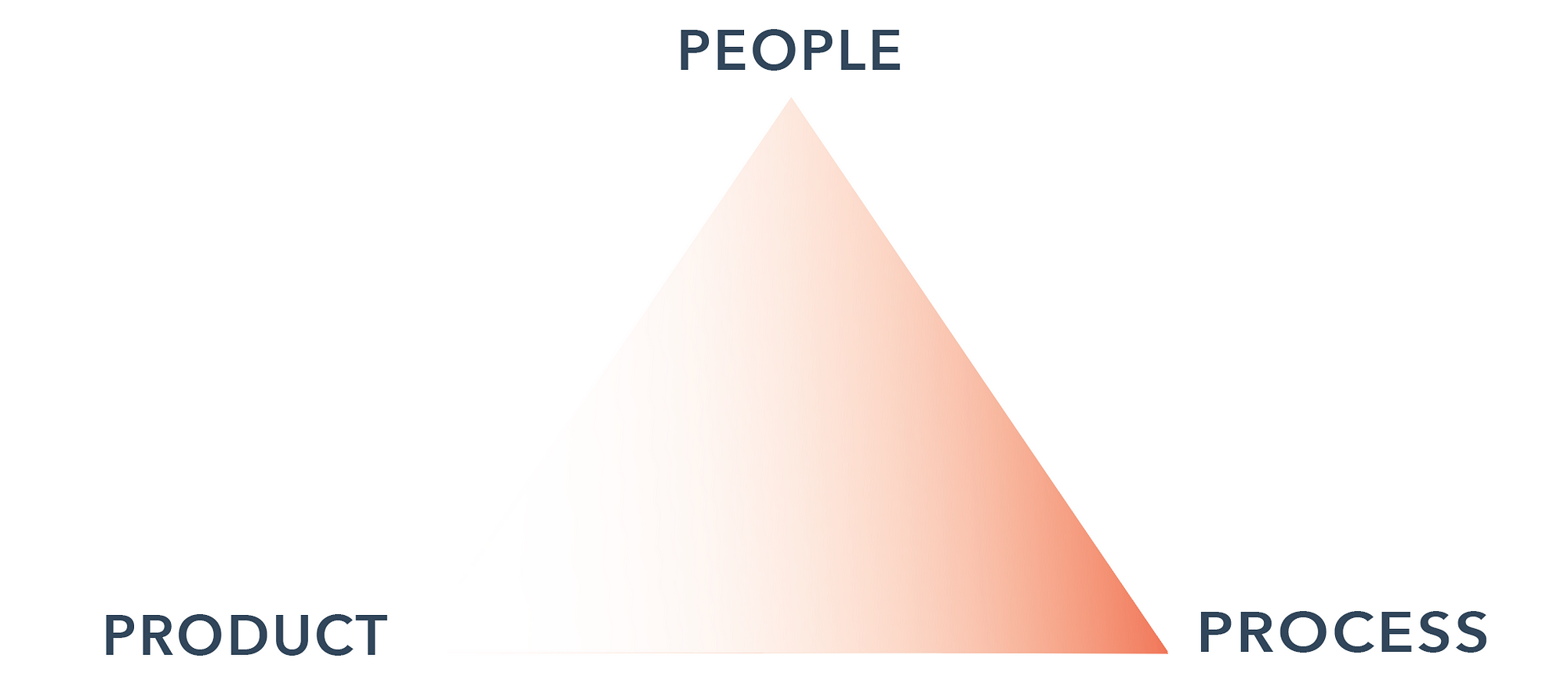

But at HubSpot, we expect HubSpot’s engineering leaders to take an active role in building great products and building great teams.

HubSpot was a process-focused organization in the early days, but we abandoned it long ago for a couple of specific reasons. Companies that heavily focus on process often do so because they have rigid expectations and looming deadlines. At companies like these, an engineering manager’s job is to create a predictable, reliable engineering team that delivers on what product owners tell them to do. They may spend a lot of their time running a software prediction process, like Scrum, in order to ensure that they’re meeting their commitments. But we have few solid deadlines at HubSpot, which means that we don’t need to subscribe to any specific methodology.

But more importantly, we want to avoid a specific anti-pattern that tends to result from process-heavy organizations: a lack of ownership of their product’s success or failure. At many companies, engineering leaders are focused on building teams that can execute, but have no say at all on what they’re executing on. Setting those priorities is the job of Product and Design. There’s no co-ownership — if the team builds the wrong thing, that’s Product or Design’s fault, and in the most extreme cases, engineering leadership does not believe that the success of the product is their responsibility.

But at HubSpot, we want everyone focused on building great products. That’s why we invest so heavily in building the relationships between Engineering, Design, and Product (we call this the Triad, and triads exist from an individual team level up to an organization level). Each of these three people has a different perspective, and each of them has a voice and a vote.

We believe that a predictable, reliable engineering team that builds the wrong thing is not a success. The engineering leader (and the engineers themselves) have to feel ownership and responsibility around what they are building, not just how they are building it.

This empowers engineering leaders to focus on figuring out how to make the team more successful, more autonomous, and more bought into their mission rather than meeting the next deadline. By owning the success or failure of the products they work on, leaders are incentivized to do whatever they need to do to build something great. And by modeling that ownership for their teams, leaders can drive that ownership all the way down the stack.

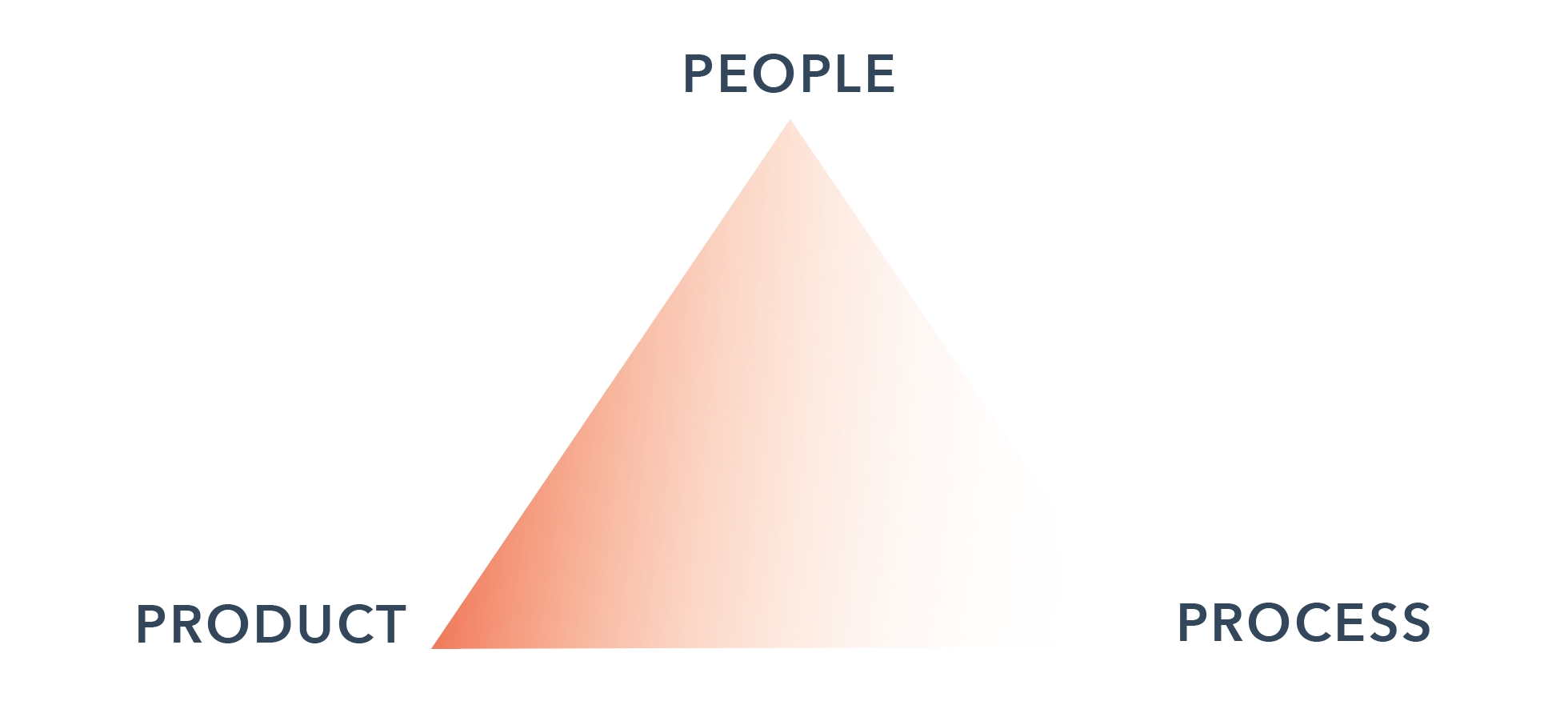

Many successful organizations fall on the people-focused side of the diagram. In fact, for a long time, that’s where HubSpot’s engineering leadership focused, too. But we started hearing feedback in our quarterly employee NPS surveys that engineers didn’t see a clear path to move up into leadership. As a growing company, that was troubling — so we decided to dig in.

We found that engineers were looking at the roles their leaders filled — roles that involved mostly people management — and saw people who were doing completely different jobs than they were. They focused on entirely different problems and had entirely different skills. Many of the engineers we talked to were already Tech Leads (which at HubSpot is a player-coach role) and they just didn’t see themselves growing into a purely people-focused leadership role.

An organizational anti-pattern can develop in engineering teams that focus too heavily on people management: a breakdown of trust between leaders and the people they lead. This most often happens when engineers feel their people managers don’t understand the technical context for their work. This lack of understanding leads to a lack of respect, and in the worst situations, engineers can start to see the people-focused work their managers do as pointless to their day-to-day jobs.

Some companies try to get around this by splitting the role of engineering leadership between two people: a people manager, and a technical leader or architect. There are obvious advantages to splitting these roles. For one, it scales better. Because each person has only one job to do, each person can specialize on one piece of the puzzle.

That approach isn’t for us. Engineering leaders at HubSpot do both jobs: they are technical leaders and they are people leaders. For one, it’s much more efficient, because when there’s just one engineering leader at the helm of a team, every conversation they have will be relevant and full of context. This means there’s less wasted time hunting for information or making decisions with incomplete data.

We care so much about having new engineering leaders understand the context for their teams that we’ve set aside the first few months of their time at HubSpot to build that context. They spend that time joining the teams they’ll eventually lead and learning from them about HubSpot’s product and stack. At the end of this time, they’re much better equipped to take the reins.

But more importantly, having two engineering leaders erases autonomy (and we really like autonomy). When responsibility is split, situations can arise where managers refuse to deal with them on the grounds that it’s “not their job”. But if you’re an engineering leader at HubSpot, it is your job — no matter what comes up. That’s because, at the end of the day, your mission is to help your team figure out how to win. If leaders are on the ground — if they’re part of the game — they’ll have an easier time coaching their teams and making plays. Teams have an easier time respecting leaders who are moving the ball; they know their leaders are on their side and their team.

We recognize that expecting our leaders to be strong technical and product leaders (while not neglecting people management) stretches them thin. To be clear, we think people management is important — every engineer at HubSpot deserves an able and engaged manager. But we try to counteract this by making people management as efficient as possible. We use automation and tools to help us do it (like 15five) and lean on our team’s HR business partners when we need to. And there’s just no substitute for talking to people, so we make sure leaders set aside some percentage of their time to make sure their employees are heard and are getting the mentorship and growth opportunities they need.

It isn’t easy finding leaders who are attuned to the hopes, fears, and needs of the people they manage, who are adept at helping a team understand and get excited about their mission, and who have a strong technical and product sense. It is aspirational. But we think it’s the model that will help us build the best products for our customers while also building teams that are happy and work well together. And we hope that by developing leaders who engineers can relate to, learn from, and grow into, we’ll be setting our organization up for success as we scale.

We’re not sure if this model will serve us well forever, but it’s the model that works for us right now.

Interested in learning more? You can read more about the culture of our product team. And if you’re an engineering leader who wants to spend more of your time helping teams build great marketing, sales, and customer success software — we’re hiring.