Is group chat making you sweat? – Signal v. Noise

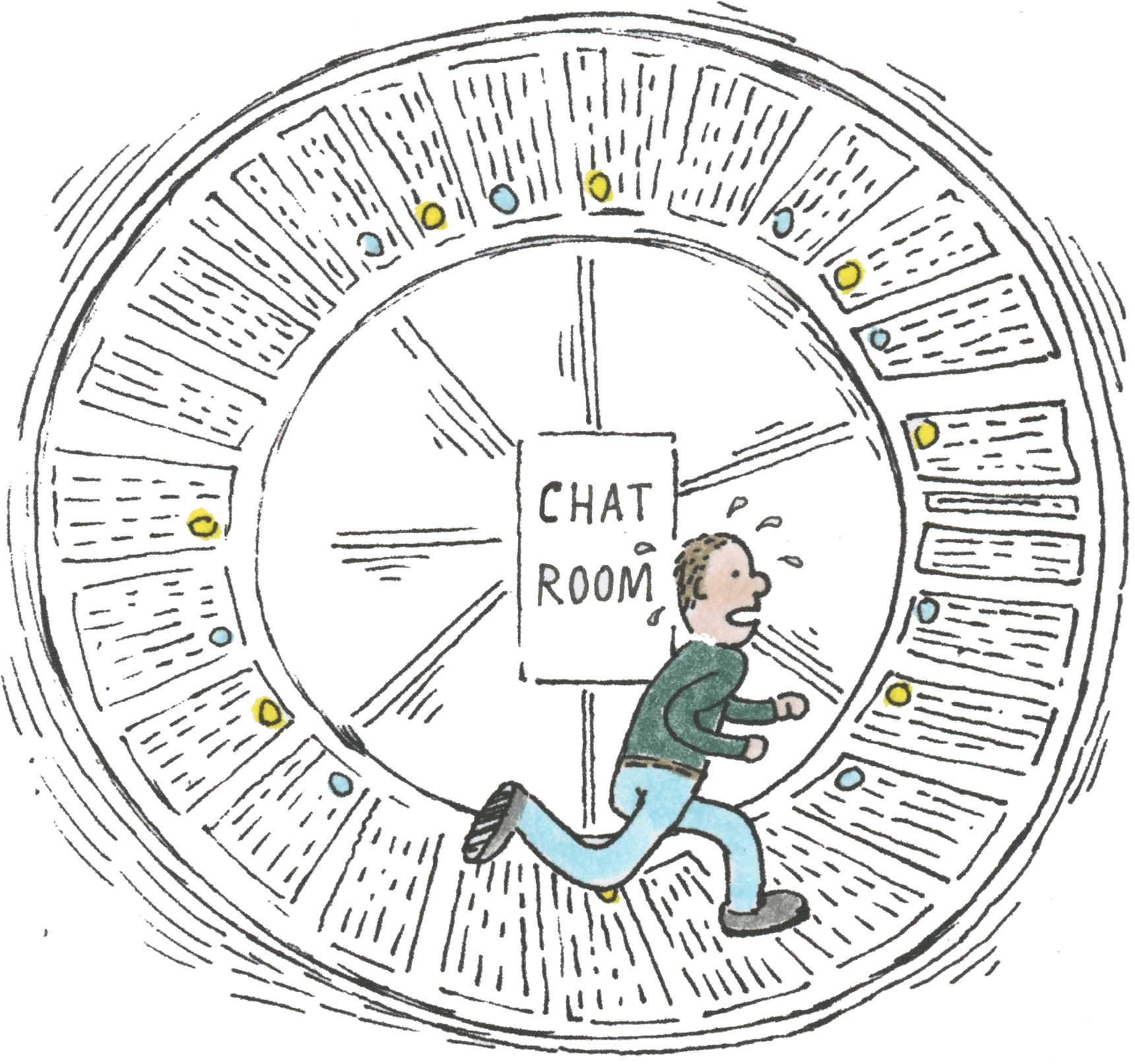

Group chat is like being in an all-day meeting with random participants and no agenda.

In 2006 we launched Campfire, the first modern SAAS group chat and messaging tool for business.

Since then, quite a few business chat and messaging tools like Hipchat, Flowdock, Slack and others have sprung up. And we’ve since rolled group chat and instant messaging (we call them “pings”) into the all new Basecamp 3.

As a company, we’ve been around group/business chat longer than just about any other company in business today. In addition to hearing from our customers for years, our own daily experiences over ten years of extensive group chatting have taught us a lot about what works and what doesn’t. All together, we’ve messaged nearly 10,000,000 lines to one another at 37signals/Basecamp since 2006.

What we’ve learned is that group chat used sparingly in a few very specific situations makes a lot of sense. What makes a lot less sense is chat as the primary, default method of communication inside an organization. A slice, yes. The whole pie, no. All sorts of eventual bad happens when a company begins thinking one-line-at-a-time most of the time.

We’ve also seen strong evidence that the method and manner in which you choose to communicate has a major influence on how people feel at work. Frazzled, exhausted, and anxious? Or calm, cool, and collected? These aren’t just states of mind, they are conditions caused by the kinds of tools we use, and the kinds of behaviors those tools encourage.

Based on these discoveries, I’ve put together a list of the positive and negative impacts of group chat on an organization. If you’ve gone chat-first, or you’re considering heading down that path, I encourage you to review and consider these impacts on your own organization.

The Positives

Group chat is great for…

1. Hashing things out quickly. When you need to toss an idea back and forth between a few people, there’s nothing better than chat. Toss in some words, drag in a picture, get some quick feedback, and move on (just get out quick before you get sucked back in).

2. Red alerts. Sometimes it’s essential to get critical information in front of people. A server’s down, a deploy failed, there’s a crisis that truly demands a group’s immediate attention. There are a variety of ways to get this instant information to people, and piping it into a high priority chat room or channel is definitely one of those ways.

3. Having fun. Fun at work is as important as work at work. And chat really works well here. Culture develops, inside jokes flow, emoji, goofing around with sounds (in Campfire), and meme generators are perfect territory for the chat room or channel.

4. A sense of belonging. This is particularly important for people who work remotely. Having a chat room where you can just say good morning, let people know you’re out for lunch, and generally just feel part of something is a powerful counter to cabin fever.

The Negatives

Group chat as the primary method of communication across a group or organization leads to…

1. Mental fatigue and exhaustion. Following group chat all day feels like being in an all-day meeting with random participants and no agenda. And in many cases, a dozen all-day meetings! You hear it from people all the time — it’s exhausting. Constant conversation, constant chatter, no start, no end. You can decide not to pay attention, but that leads to a fear of missing out.

2. An ASAP culture. Now! At its very core, group chat and real-time communication is all about now. That’s why in some select circumstances it really shines. But chat conditions us to believe everything’s worth discussing quickly right now, except that hardly anything is. Turns out, very few things require ASAP attention. Further, ASAP is inflationary — it devalues any request that doesn’t say ASAP. Before you know it, the only way to get anything done is by throwing it in front of people and asking for their immediate feedback. It’s like you’re constantly tapping everyone’s shoulder — or pulling on everyone’s shirt — to get them to stop what they’re doing and turn around to address what’s on your mind. It’s not a sustainable practice.

3. Fear of missing out or not having a say. If you’re not paying attention all the time, you won’t be able to have your say when something comes up. And since conversations happen quick, and then scroll away on the conveyor belt, if you’re not at your station when it’s your turn to speak, you won’t get a chance later. This encourages people to watch rooms/channels all day to see if a conversation comes up that they feel like they need to dive into.

4. Thinking a line at a time rather than a thought at a time. Most things worth discussing at length are worth discussing in detail over time. Because chat is presented one line at a time, complete thoughts have to unfold one line-at-a-time. But since people can jump in any time before you’ve had a chance to fully present yourself, making a point can become really frustrating really quickly. Further, incomplete thoughts and staccato responses make it really difficult to fully consider a topic and make important decisions — especially in a group setting. Imagine being in a meeting where everyone just spoke one line at a time, and people kept interrupting you while you were trying to make your point. Would you ever get anywhere? And wouldn’t it take forever?

5. Implied consensus. “Because we talked about it in the chat room, everyone who needs to know now knows”. You know how it goes — people talk about some work in the chat room and nobody objects. That leads people to assume everyone read that discussion and agreed. Except that they weren’t, or they didn’t. Decisions get made without people’s consent because they weren’t there at the very moment it was discussed. This ties back to many of the points above — “right now” is rarely the moment to both have the discussion and come to a conclusion.

6. Knee-jerk responses. Discussing something in a chat room is like being on the shot clock. There’s a small window of time to be heard before the point you want to respond to scrolls away. So people often just yell something out just to be heard. The same phenomenon can be seen on Twitter. An accelerating conversation leads to shallow sound bytes and talking points — no different than talking heads on TV that only have 3 minutes to make their point before the segment ends.

7. Pile-ons and devolving conversations. A few people start talking about something. They’re doing great. But then another person tosses in a drive-by one-liner comment that takes the conversation in a new direction — and often not a good one. Then someone else comes in and tosses their 2 cents in. The original folks begin to lose control of the conversation. Something that was being discussed by just a few people ends up being a 6+ person conversation. Things devolve quickly. The medium encourages this breakdown since anyone can pop in and step right into any conversation without having the opportunity to get up to speed on the back-story. They may start strong, but conversations rarely get better over chat.

8. Rambling and repetition. Conversations that should take a few minutes often go on for 20+ when they happen over group chat. Continuous conversations among a group of people are very difficult to end — especially when new people can pop in to drop in their quick 2 cents at any time. Just when you feel like the conversation is almost over, they can start right up again — often rehashing what’s already been discussed before. “We’ve already talked about this!” is a common refrain heard in chat rooms around the world.

9. Over-informing everyone in real-time. I was talking to a guy a few days ago who was fired up about piping in sales data into a popular chat room whenever they made a sale. I asked him how many times that was a day. He said “dozens”. I said, so that’s dozen incremented unread counters in this one room throughout the day? He said yes. Then he said, “Is that bad?”. I said, do you think everyone need to know that sale happened right now? Might it be better to summarize sales once a day so you don’t interrupt people by incrementing an unread counter on everyone in the company a dozen times a day? He hadn’t even considered the impact, but now he’s seen the light. Be careful — it’s fun to hook things up and pipe stuff in, but what are the costs to people’s attention? Is it worth potentially pulling them away from their work a dozen times a day (you know how people love checking unreads) just to tell them something that could have waited until later?

10. Chat reminds you that you’re behind. Group chat feels like you’re chasing something all day long. What’s worse, group chat often causes “return anxiety” — a feeling of dread when you’re away for a while and you come back to dozens (hundreds?) of unread lines. Are you supposed to read each one? If you don’t, you might miss something important. So you read up or skip out at your own risk. All the while you’re trying to piece together interleaving conversations that may refer to other things you haven’t seen yet. And just when you’re caught up, you’re behind again. It’s like your working two jobs — the work you’re supposed to do, and the work of catching up on what you missed that probably didn’t matter (but you won’t know until you read back).

11. 25 used to mean 1. If you have one unread email, you see a “1” in your inbox. That one unread may be a complete thought, a dozen lines, or maybe even longer. But it’s a “1”. 1 unit to absorb. Compare that with the number of lines it takes to communicate the same thing in chat. Since chat is mostly one-line-at-a-time — even long lines — it’s an unread multiplier. A conversation that used to be a 1 or a 2 in email, is now a 25 or 40 or 100+. Plus all the other replies that come in as someone’s talking. Group chat breeds big numbers. The bigger the numbers, the more you’re missing. And the vicious cycle continues. This takes a mental toll.

12. Unread what? When conversations are represented by numbers in badges next to broad category/room/channel names, you have to enter to see what’s new and worth your attention. The number doesn’t communicate what something is about, only that there’s something new to see. This makes it hard to judge what’s behind the number, so you have to enter the conversation already in progress just to find out what’s being discussed. This often pulls you into conversations that you don’t need to be part of right now. Contrast this with email’s tightly scoped subject headers and a readable list of participants that help you decide if you need to deal with it now, later, or not at all.

13. Manic context-shifting and continuous partial attention. Most teams keep a chat window open all day on the side of their screen or on a second monitor. This invites you to keep one eye on the chat window, and the other on your work. Problem is that chat window is a black hole for your attention — constantly pulling your gaze, constantly chipping away at your focus. Playing whack-a-mole with unread indicators across dozens of rooms/channels causes manic context-shifting. Context-shifting robs you of uninterrupted stretches of time to concentrate on the work you’re supposed to be doing. Further, like your muscles remember repetitive tasks (muscle memory), your mind does too — and jumping around rapidly between conversations all day creates “attention residue” that makes it hard to clear your mind of the previous conversation before starting the next conversation. This makes it difficult to fully consider the conversation you’re about to enter. More on this in this wonderful Economist article.

14. An inability to review and reference later. Ever try to go back and find an important conversation in a chat room or channel? Maybe you find a chunk, but how do you know if it’s the whole thing? Maybe the same thing was discussed with a different outcome a week before. Or 230 scrolls before. An endless conveyor belt of conversation turns everything into a series of fragmented moments where the big picture and full record is never clear. Where does it start? Where does it end? How do you know who’s seen some of it, all of it, none of it?

15. Lack of context. When things are discussed in the same space, and the only separator is time, discussions lack context. It’s very hard to say “This conversation is about this document” because that document ultimately lives somewhere else, and the conversation is detached from the original source material. When you look at the document later, it’s unclear if there was a conversation about this document because the conversation lives elsewhere. This is a subtle point, but an extremely important one.

16. Presence, assumptions, and expectations. Many chat platforms put a little green dot next to people telling you they are online/available. That’s called presence, and it’s worse than you might expect. It’s professional pressure to stay logged into chat. It’s saying “if you aren’t green, you aren’t at work”. Quitting chat suggests you aren’t part of the group. And that pressure forces you to keep a chat room open all day. Which forces you to absorb the blows of all-day distractions while you’re trying to actually get the work done you’re supposed to be doing. It’s just a modern version of the outdated butts in seats. Sure you can say do not disturb, but the true version of do not disturb is quitting the app.

17. Communication across time-zones. Chat is often hailed as the essential tool for working remotely. And it is an important tool in the remote workers toolbox, but it’s a particularly bad one when you’re trying to work with people across time zones. Since chat is perpetually pointed towards now, and everyone’s now is different (your 9am is my 11am is her 3pm is his 8pm), real-time is the wrong time. Asynchronous communication is far better when working with teams spread across the world or even just a few time zones apart.

Wow, jeez? You must really have something against persistent group chat as a primary method of communication? Yes, in most cases I do. And it’s only because we’ve been using it at 37signals/Basecamp for 10 years. I’ve seen the distraction, anxiety, stress, and misunderstanding it can cause, and those are things that can really damage people and an organization.

I believe attention is one of your most precious resources. If something else controls my attention, that something else controls what I’m capable of. I also believe your full attention is required to do great work. So when something like a pile of group chats, and the expectations that come along with them, systematically steals that resource from me, I consider it a potential enemy. “Right now” is a resource worth conserving, not wasting.

That said, I still think group chat is an important tool in the communications toolbox. I just don’t think it’s the go-to tool. I think it’s the exception tool. It’s far more useful for special cases than general cases. When used appropriately, sparingly, and in the right context at the right time, it’s great. You just really have to contain it, know when not to use it, and watch behavior and mood otherwise it can take over and mess up a really good thing.

And to be fair, these problems aren’t exclusive to group chat. However, the fundamentals of group chat (many people right now, one line at a time incomplete thoughts, fear of missing out (FOMO), low barriers to participation which leads to over-participation, incessant notifications, etc) tends to amplify the unintended negative consequences. You can’t separate effect from the cause.

What’s even more interesting is that 1-on-1, direct messaging/texting is a lot like email — it’s often used asynchronously. You leave something for someone else and you can be pretty sure they’ll see it when they get back to it. But in a group chat setting you can’t be sure because other people can carry on the conversation and push stuff out of the way. There are remedies for this like @mentions and starring and all that, but those are crutches and band-aids that try to mask the fatal flaw of communication on a conveyor belt that moves at different speeds depending on the number of participants. Great group communication is predictable — group chat is anything but predictable.

As Osmo Wiio said, Communication usually fails, except by accident. And that’s why I think it’s so important to really think through the impact chat as the primary method of communication can have on an organization.

So here’s what we’re trying to do

Real-time sometimes, asynchronous most of the time.

At Basecamp our perfect-world rule of thumb is “real-time sometimes, asynchronous most of the time”. Admittedly, we have some work to do there to live up to this ideal. We still lean on chat too much, and I’d like to see us make a major effort to cut back.

Basically, right now should be the exception, not the rule. That creates space and attention for the things that really do have to be discussed right now, and allows everything else to be thoroughly discussed asynchronously and thoughtfully over time.

For example, in Basecamp 3 (which is obviously what we use to run all our projects, work, and company-wide communication), we use the built-in campfire chat for occasional real-time communication while important asynchronous communication happens on message boards and comment threads that are attached to every object in Basecamp (to-do lists, individual to-dos, documents, announcements, check-ins, etc). Comment threads also keep things in-context since discussions about a to-do (or document or file or announcement or…) are permanently attached to that to-d0 (or document or file or announcement or…). This way you can easily refer back to any conversation about something you’re working on and be absolutely confident you have the whole story and the complete conversation in one place.

Even if you use something other than Basecamp, here’s some general advice on how to make the real-time/asynchronous split work in your organization:

- Stop expecting everyone to be in chat all day long. Don’t set an expectation that people should have a chat window open all day. Make chat something you bounce into and out of purposefully, not stick around all day.

- If it’s important, slow down. If it’s an important conversation, it shouldn’t happen in the chat room. Chat should be about quick, ephemeral things. Important topics need time, traction, and separation from the rest of the chatter.

- Announcements aren’t chats. Related to the point above, if you have to make a company/group-wide announcement you need to make sure everyone sees, don’t post it in the chat room. Send it asynchronously (via something like Basecamp or email or whatever you use that provides asynchronous communication options).

- Give everyone a chance to consider and have a say on a reasonable schedule. Thoughtful feedback isn’t just an answer, it’s time + an answer. Time is a key component to formulating a complete thought. So create some time for people by asking for feedback asynchronously — let people respond on their own time. You can set a limit like “I need feedback by tomorrow” or “We’ll keep this topic open until the end of the day Wednesday” to set boundaries and limits.

- Treat chat like a sauna — stay a while but then get out. Find yourself staying in a room/channel too long? Think about it like a sauna or a hot tub. It feels good for a while, but it’s unhealthy to stay too long.

- Treat group chats like conference calls — don’t get everyone on the line. The smaller the chat the better the chat. Think of it like a conference call. A conference call with 3 people is perfect. A call with 6 or 7 is chaotic and woefully inefficient. Group chats are no different. Be careful inviting the whole gang when you only need a few.

- Tell people to “write it up” instead. Stuck in a chat that’s going on way too long? Talking a lot but not making progress? Stop the conversation and ask someone to “write it up” — take it to long-form, make it asynchronous. Let someone make a complete point all at once and then give people time to absorb it and respond in kind, over time.

- Summarize rather than drip information. Rather than pipe in every single occurrence of something the moment it happens, consider summarizing once or twice a day. It’ll help cut down on distractions.

- Give people long uninterrupted stretches to get work done. Interruptions are the enemy of productivity, and group chat has become the greatest interruption factory at work. If you want people to do great work, you have to give them the appropriate time and space to get into the zone. Chunks of time — 15 minutes here, 30 minutes there, 7 minutes here — aren’t going to do it. People need hours of interrupted time. Every time that unread indicator appears, it’s temptation for people to break away from what they’re doing to check in. Be mindful of the cost of those interruptions. Are they worth it? Think about it like sleep. If someone was interrupted every 15 minutes while they were trying to sleep, you wouldn’t think they’d be getting a good night’s sleep. So how can getting interrupted all day long lead to a good day’s work?

- Set expectations that it’s OK to be unavailable. If you can turn off presence, turn it off. If you can’t, make sure people understand that it’s OK to be unavailable. That turning off chat — quitting, closing, snoozing, whatever — should be perfectly acceptable. If someone’s not available it should signal that they’re working, not taking a break.

In the end, this isn’t about a specific tool or specific product. It’s about a method of communication — one that rides a-line-at-a-time on a variable speed conveyor belt where no one is in control of how fast or slow it goes. Where things can stick around stationary for hours or days, or things can blast by you in seconds.

Understanding the positives and negatives, and how they play off one another, is central to getting the most out of something. Knowing the tradeoffs helps you assign value. Ignoring the cons because the pros are so good, or dismissing the pros because the cons are so bad, leaves you with a false sense of comfort and a cloudy picture of the reality on the ground.

There are lots of managers out there who love group chat because they can pop-in-and-out quickly and speak to many people at once, but there are a lot of employees out there sweating all day long trying to keep up appearances of being involved but knowing they have actual work to do. They can’t stop thinking about how they’re going to have to work late. They can’t stop thinking about how the constant distractions during the week days means that Sunday night now belongs to their job. It’s absolutely a real problem.

It’s common in the software industry to blame the users. It’s the user’s fault. They don’t know how to use it. They’re using it wrong. They need to do this or do that. But the reality is that tools encourage specific behaviors. A product is a series of design decisions with a specific outcome in mind. Yes, you can use tools as they weren’t intended, but most people follow the patterns suggested by the design. And so in the end, if people are exhausted and feeling unable to keep up, it’s the tool’s fault, not the user’s fault. If the design leads to stress, it’s a bad design.

So, whichever side you’re on, whatever tools you use, keep in mind how they affect other people, not just what they appear to help you get done. Done doesn’t matter if people are wrecked along the way.

I’d love for this post to start a broader industry-wide discussion about the impact tools have on people, not just on work. I’d love to speak on it at conferences, events, workshops, etc. Please get in touch with me via email if you have something to say, or want me to say more. Thanks for reading.