GOOGLE MAPS’S MOAT

How far ahead of Apple Maps is Google Maps?

DECEMBER 2017

⚠️ Tap or click any image to enlarge

Over the past year, we’ve been comparing Google Maps and Apple Maps in New York, San Francisco, and London—but some of the biggest differences are outside of large cities.

Take my childhood neighborhood in rural Illinois. Here the maps are strikingly different, and Apple’s looks empty compared to Google’s:

Similar to what we saw earlier this year at Patricia’s Green in San Francisco, Apple’s parks are missing their green shapes. But perhaps the biggest difference is the building footprints: Google seems to have them all, while Apple doesn’t have any.

But it’s not just Apple—no one else seems to have them either:

Only Google has buildings here.

But if we had looked at this same area just a couple years ago, we wouldn’t have seen any buildings on Google’s map. The buildings are a new thing, and I’ve been watching Google gradually add them over the past year:

But “buildings” is the wrong word to describe what Google’s been adding; it’s more like “structures”. Because not only has Google been adding houses, it’s been adding garages and tool sheds:

And park shelters:

And even trailers:

Now if the trailers are the least architecturally sophisticated structures in my hometown, then the churches are probably the most—and here’s where things get really interesting:

Notice the detail. (Google even has the front steps.)

And it’s not just churches that are this detailed…

Here’s the post office:

And the town’s biggest house:

Again, this isn’t some big, bustling city, like San Francisco or New York or even Naperville. It’s a small, rural town.

It’s so rural, its roads are among the 1% of U.S. roads that Google hasn’t Street View’d:

Street View vehicles once drove across the main routes nine years ago—but they never returned to capture the rest. So why was Google quietly adding all of this detail to a town it had never bothered to Street View?

I started looking at other towns nearby, and Google had buildings in all of them too. Here’s one ten times smaller than mine, a town of 1,000:

And here’s one ten times smaller than that—a town of just 100:

Ten times smaller than 100 is 10—and according to the 2016 census estimates, there’s no town that small in my home state. But there are a couple with populations of just 13. Here’s one of them:

More buildings.

But while Google has buildings in my home state’s smallest towns, Apple doesn’t have them in the majority of U.S. state capitals.

Here’s Salem, Oregon:

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania:

Olympia, Washington:

And twenty-five more capitals:

In fairness to Apple, some of these capitals are pretty small. Then again, Apple doesn’t even have buildings in parts of the U.S.’s three largest cities.

Here’s the University of Chicago in Chicago:

Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles:

And Queens, New York:

And even in areas where Apple does have buildings, Google’s are generally much more detailed—such as here in downtown San Francisco:

The building centered above has a number of satellite dishes on its roof:

Now look again at Google’s map… do you see them?

A couple blocks away, another building has a row of five fans on its roof:

Now look at Google’s map… Google’s buildings are so detailed, you can discern the HVAC units:

And it’s not just the downtown skyscrapers that are detailed. Here’s one of the hotels on Nob Hill, the Mark Hopkins:

And here it is on Google and Apple:

Meanwhile, here’s a cathedral a couple blocks away:

And a high school over in the next neighborhood:

Many of the homes in San Francisco have bay windows, like these:

And Google’s buildings are so detailed, you can tell which houses have bay windows:

* * *

Google had buildings as early as 2007 in a handful of major cities—but they weren’t nearly as detailed as today’s:

Sometime between now and then, their detail and coverage dramatically increased.

But when?

Browsing through Google’s old press releases, it appears that Google added the first 1,000 of these detailed buildings back in 2012:

Most of these 1,000 buildings were landmarks, like the Florence’s Cathedral and the Sydney Opera House. But just a few months later, this initial trickle of buildings suddenly became a deluge as Google started adding whole metro areas:

Now, you can see 25 million new building footprints that have been added to Google Maps on desktop and mobile across major metropolitan regions in the United States, including Houston, Los Angeles, Chicago, Miami, and the San Francisco Bay Area.

In that same press release, Google also reveals how it’s making them:

These building footprints, complete with height detail, are algorithmically created by taking aerial imagery and using computer vision techniques to render the building shapes.

And this is even how Google is making complex structures, like Seattle’s Space Needle:

For landmarks like Seattle’s Space Needle, computer vision techniques extract detailed 3D models.

So Google is creating all of these buildings out of its aerial and satellite imagery:

And reexamining my hometown’s buildings, this makes sense. They almost perfectly match Google’s imagery:

But what’s most interesting is how fast Google is making these buildings.

Just two years after it started adding them, Google already had the majority of buildings in the U.S. And now after five years, it has my rural hometown—an area it still hasn’t Street View’d (after 10+ years of Street View).

So the satellites seem to be outpacing the Street View vehicles.

And this building-generation process seems automated to such a degree that buildings sometimes appear on Google’s map before roads do:

At the rate it’s going, how long until Google has every structure on Earth?

But these buildings are more than just a pretty detail—they appear to be the foundation for one of Google Maps’s newest features…

* * *

DATA ALCHEMY

If you asked someone to sketch a map of their city, what would they draw? And how closely would it resemble the maps we commonly use?

Rachelle Annechino and Yo-Shang Cheng explored these questions in their 2011 masters thesis, “Visualizing Mental Maps of San Francisco”:

As part of their study, they interviewed twenty-two San Francisco residents and asked each to sketch a map of the city.

Across the sketches and interviews, Annechino and Cheng observed a common theme in how the interviewees described the city:

We found that people tended to conceptualize San Francisco in terms of “main drags” and “mini cities”—commercial corridors that attract people

Many of San Francisco’s neighborhoods have a single street that commercial activity is centered around. And these “main drags” or “commercial corridors” act as destinations, attracting people from other parts of the city.

Using zoning maps and information from the interviews, Annechino and Cheng identified twenty-seven “commercial corridors” within San Francisco:

Of course, these “commercial corridors” aren’t just a San Francisco thing—almost every city has them. (Even my tiny hometown has a few.) And they’re not only relevant for residents, they’re also important to travelers:

“Which areas have a lot of restaurants and shops within walking distance?”

“I just got off the freeway, where’s the business district?”

But the map isn’t always the territory, and the locations of these corridors aren’t immediately obvious on most online maps. Up until last year, this was even true of Google Maps. Let me show you…

Patricia’s Green (the park from “A Year of Google & Apple Maps”) actually sits along one of these commercial corridors in San Francisco, the Hayes Street corridor:

Now let’s take last year’s version of Google Maps and zoom in to this corridor:

Notice that it isn’t until z18—one of Google’s very last zooms—that we begin seeing businesses clustered along Hayes Street. In other words, we can’t tell that Hayes Street is a commercial corridor until we’re already so zoomed in, it’s the only thing in view.

See the problem?

There’s no way to look at a map of a city and quickly spot the commercial corridors. Look again at San Francisco: there’s no hint that the corridors (the black lines) are actually there:

Of course, much of the problem is that we’re trying to find the corridors by looking for clusters of place labels (e.g., restaurants, shops, etc.). And place labels, like any other kind of map label, are subject to a number of design constraints:

They have to be large enough to be legible.

They can’t overlap.

They can’t be placed too close together.

And they have to coexist with other kinds of map labels, like roads and neighborhoods.

Because of these constraints, there’s a limit to the number of places that can labeled on most zooms. And this limit prevents us from seeing clusters of businesses until we’re zoomed in really far.

So how could Google solve this?

At some point, Google likely realized it already had…

If we look at Google’s Bay Area map, we see a handful of cities:

But there’s actually many more cities here than Google is labeling:

Because city labels are subject to the same design constraints as place labels (e.g., can’t overlap, can’t be too close together, etc.), Google can only fit a handful of cities here.

But even though Google can’t label every city, it’s still useful to know that there’s a density of cities here—so Google communicates this with a special shading:

At some point, Google realized that just as it uses shadings to convey densities of cities, it could also use shadings to convey densities of businesses. And it shipped these copper-colored shadings last year as part its Summer redesign, calling them “Areas of Interest”:

What’s more, these “Areas of Interest” managed to capture all of Annechino’s and Cheng’s commercial corridors:

Annechino and Cheng spent months researching one city. But not only did Google capture all of their commerical corridors (and several more), it somehow came up with them for thousands of cities across the world. (Even my tiny hometown got a few.)

How did Google scale this?

But not only that, Google’s “Areas of Interest” (“AOIs”) are much more detailed than Annechino’s and Cheng’s corridors—notice that they have very specific and granular shapes:

Where are these shapes coming from?

Google has said surprisingly little about how it’s making AOIs—just that they’re generated using an “algorithmic process” that identifies “areas with the highest concentrations of restaurants, bars and shops”.

So it sounds as if Google is making AOIs out of certain kinds of places, like restaurants, bars, and shops:

But this still doesn’t explain the detailed shapes. Businesses are shown as circular icons, but AOIs aren’t circular. Nor are they heat maps. Rather, they’re boxy and rectangular…. almost like buildings.

Zooming in to get a closer look, the AOI shapes fade out just as buildings begin appearing on the map…

…but there’s a single zoom where, for a brief moment, AOIs and buildings appear together:

And this zoom seems to offer us a clue…

Let’s take the map above and, using Google Maps’s styling API, let’s remove everything other than the buildings and the AOIs:

With everything removed, we see that the AOI generally has a rectangular shape…

…but there are a number of places where the rectangle juts out, and these juts align with many of the buildings:

So it seems as if buildings are informing the AOI shapes.

About a mile west, there’s a different AOI centered along Haight Street. Here again, buildings seem to influence the AOI’s overall shape:

And we see the same over at another AOI along Mission Street:

But there’s a second pattern… do you see it?

The juts only happen when orange buildings go outside the rectangle. Take another look:

This “juts-at-orange-buildings” thing seems to be a pattern with every AOI.

Here’s another one in the Sunset District:

The orange buildings are clearly giving the AOI its jagged shape.

But what are these orange buildings?

All of Google Maps’s buildings were grey until the day that AOIs were introduced in July 2016. That day, some of Google Maps’s buildings turned orange:

But why did they turn orange?

Looking closer, it seems that the orange buildings are buildings with specific kinds of businesses inside of them, specifically restaurants and shops:

This suggests that Google took its buildings and crunched them against its places. In other words, Google appears to be creating these orange buildings by matching its building and place datasets together:

And Google’s “Areas of Interest” are shapes that are being algorithmically generated around high densities of these orange buildings:

So Google seems to be creating AOIs out of its building and place data. But what’s most interesting is that Google’s building and place data are themselves extracted from other Google Maps features.

As we saw earlier, Google’s buildings are created out of the imagery it gathers for its Satellite View:

And as we saw in “A Year of Google & Apple Maps”, Google has been using computer vision and machine learning to extract business names and locations from its Street View imagery:

In other words, Google’s buildings are byproducts of its Satellite/Aerial imagery. And some of Google’s places are byproducts of its Street View imagery…

…so this makes AOIs a byproduct of byproducts:

This is bonkers, isn’t it?

Google is creating data out of data.

* * *

THE MOAT

With “Areas of Interest”, Google has a feature that Apple doesn’t have. But it’s unclear if Apple could add this feature to its map in the near future.

The challenge for Apple is that AOIs aren’t collected—they’re created. And Apple appears to be missing the ingredients to create AOIs at the same quality, coverage, and scale as Google.

As we saw, buildings appear to be a crucial ingredient:

And prior to releasing AOIs, Google spent at least four years amassing a worldwide dataset of imagery-extracted buildings:

Around the same time that Google started adding these imagery-extracted buildings to its map, it also started adding 3D models of metropolitan areas to Google Earth…

And like Google’s buildings, these 3D city models are also created from Google’s aerial imagery:

Watching the video above, it seems that Google’s buildings and 3D city models are created by a very similar process. (Maybe even the same process?)

Now what’s interesting about all of this is that Apple announced its own 3D city model feature, called “Flyover”, just five days after Google did in 2012…

…so this means that Apple, like Google, has also been collecting aerial imagery—and that it’s been doing this for at least the last five years. (As of this writing, Apple has collected imagery for more than 300 cities and areas, worldwide.)

But unlike Google, Apple doesn’t appear to be extracting buildings out of its imagery. For example, both Google and Apple have 3D models of the University of Chicago campus:

But as we saw earlier, only Google’s map has buildings here:

Meanwhile, Google and Apple both also have 3D models of Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles:

But as we saw, only Google’s map has buildings here:

And Google and Apple both have 3D models of Queens:

But again, only Google has buildings here:

So Apple doesn’t appear to be extracting buildings from its imagery.

And in areas where Apple does have buildings, it appears that they’re being sourced from third-parties, such as TomTom (Apple’s primary data provider).

In Chicago, for instance, Apple’s building coverage abruptly stops in the middle of the same blocks as TomTom’s:

And we see the same in other U.S. cities where Apple has buildings:

So Apple is either using TomTom’s building data, or TomTom and Apple are both getting buildings from the same third-party.

But this just further shows that Apple hasn’t been extracting buildings out its imagery. And because Apple hasn’t been doing this, it hasn’t amassed the global dataset of buildings it needs to make AOIs at the same scale as Google.

* * *

Another crucial ingredient for AOIs is place data.

And as we saw earlier, Google has scanned more than 80 billion of its Street View images for place and business information.

In 2015, Apple deployed its own mysterious fleet of data collection vehicles in cities around the world:

Many have speculated that Apple is collecting its own Street View imagery. But given what we saw a few months ago at Patricia’s Green, it doesn’t appear that Apple is extracting place data from whatever these vans are collecting.

If you remember from “A Year of Google & Apple Maps”, there was a group of three auto service-related businesses (Domport Auto Body Service, Fell Street Auto Service, and California Detailing) near the southeast corner of Patricia’s Green:

Google had distinct locations for each; but Apple plotted them all at the same location:

And we saw the same on the park’s northwest corner: Timbuk2 and La Boulangerie occupy the ground floor of the same building:

Google plotted them in separate locations, showing both. But Apple plotted them in the same location:

So if Apple had been extracting place data from street-level imagery since 2015, wouldn’t these businesses have been better placed?

Even today, there are similar situations across San Francisco. For example, as of this writing, Apple labels San Francisco’s tallest building, Salesforce Tower, across the street from it’s actual location:

So it doesn’t appear as if Apple is extracting place data from whatever its vehicles are collecting. And if this is true, then Apple is still a couple stages behind Google in map-making:

Google has repeatedly told journalists that it started extracting data from Street View imagery in 2008, as part of its “Ground Truth” project. So this suggests that Google may have a 6+ year lead over Apple in data collection:

And as we saw with AOIs, Google has gathered so much data, in so many areas, that it’s now crunching it together and creating features that Apple can’t make—surrounding Google Maps with a moat of time., ,

It makes you wonder how long back Google was planning all of this—and what it’s planning next…

As we saw earlier, Google seems to have associated its building and place datasets together:

So Google likely knows what’s inside all of the buildings it has extracted. And as Google gets closer and closer to capturing every building in the world, it’s likely that Google will start highlighting / lighting up buildings related to queries and search results.

This will be really cool when Google’s/Waymo’s self-driving cars have AR displays. One can imagine pointing out the window at a building and being able to see what’s inside. Or having destinations highlighted, like in Microsoft’s 2012 “Future Vision” video:

Speaking of Google’s self-driving cars, there was recent news that Google was using them to start its own Uber-style ride-hailing service.

That sounds great—but living in San Francisco, it’s hard to imagine this working smoothly. That’s because half the time I request a ride, I have to text/call the driver to coordinate my pickup spot. And I’m not alone—here’s Nilay Patel, writing in The Verge:

I call an Uber to my apartment building, and the driver gets lost because they can’t find the door.

See, the address of my building is on a main street, but the actual entrances are on the sides of the building—and when I drop a pin at those locations, Uber maps them to nonexistent addresses. So the drivers either pull up to the correct building address and don’t see a door, or they pull up to a door that has a wildly different address on it.

For the moment, it’s a pretty minor issue—the easiest solution is just for the drivers to call the rider, and it works itself out. But you can’t call a self-driving car and say “oh, I live in the white building and the door is around the corner”.

Address issues like these aren’t unique to cities. In rural areas, addresses often correspond to mailboxes that aren’t anywhere near their respective houses:

So how will Google solve this?

Probably just like it solved AOIs: by making data out of data.

As we saw, Google’s aerial imagery gives it the shape of every building. And Google’s Street View imagery gives it the location of every door:

I think you can probably see where this is going…,

AOIs are just a taste of what’s coming.

__

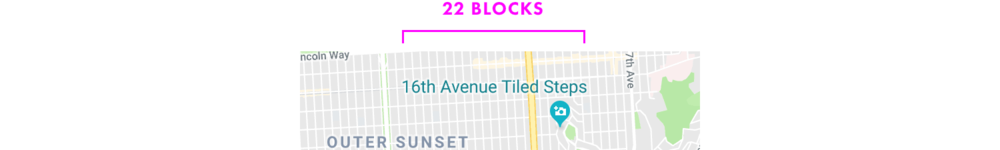

1 “It’s so rural, its roads are among the 1% of U.S. roads that Google hasn’t Street View’d.”

In 2014, Google told Wired that its Street View vehicles had driven “more than 7 million miles, including 99 percent of the public roads in the U.S.”

(Given that Google started Street View in 2007, this also tells us that it took Google’s Street View vehicles seven years to drive 99% of the U.S.)

2 In downtown Los Angeles, Google’s buildings are so detailed that you can sometimes see the blades inside the rooftop fans.

3 “They have to be large enough to be legible…” Because of this, it’s not uncommon for some labels to occupy dozens of city blocks.

4 “Google has said surprisingly little about how it’s making AOIs…” Google’s secretiveness in how it’s making AOIs has been somewhat to its detriment, as bloggers and journalists have drawn their own (sometimes unflattering) conclusions.

5 AOIs also say a lot about Google’s confidence in the accuracy of its place data and its ability to keep AOIs up-to-date. (I.e., Google feels its place data is accurate enough to build new features off of it.)

6 This whole “byproduct” thing reminds of Kingsford Charcoal’s origin story. From Rework by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson:

Henry Ford learned of a process for turning wood scraps from the production of Model T’s into charcoal briquets. He built a charcoal plant and Ford Charcoal was created (later renamed Kingsford Charcoal). Today, Kingsford is still the leading manufacturer of charcoal in America.

It’s cool to see how cleverly Google is using its own byproducts.

7 There’s a small number of buildings, such as Apple’s Cupertino campuses, that Apple is making itself. But these buildings are handmade by artists rather than by algorithms.

8 Given how many Apple employees live in and around San Francisco, you’d expect that San Francisco would be one of the first places where Apple would be extracting place data from imagery. (I.e., San Francisco would seem to be the perfect test ground, given its high density of businesses and year-round good weather, minus Karl.)

9 It’s interesting to ponder what this means for Google’s competitors. It’s no longer enough to simply collect data. Now to compete with Google, you also have to process that data and make new features out of it. Hence, the “moat”.

It’s also interesting to ponder what this means for OpenStreetMap.

10 Another advantage of Google collecting its own data is that it owns everything it collects. And because of this, it can do things with its data that Apple might be restricted from doing (because Apple seems to license most of its data from third-parties).

(Often in map licensing agreements, if you stop licensing the data, you lose the right to anything that was derived from it.)

11 Assuming Google’s efforts don’t slow (and they show no sign of slowing), is it even possible for Apple to catch up to Google?

Google’s lead in data is reminiscent of Apple’s lead in smartphones in 2007.

12 “It makes you wonder how long back Google was planning all of this…” Did Google see its Street View and aerial/satellite imagery as MVPs for the later features, like the buildings and the AOIs?

How far back was the product roadmap planned? And did the roadmap deliberately prioritize difficult-to-replicate features?

13 Here, I’m assuming that there will be cameras inside of Google’s/Waymo’s self-driving cars that will detect when you’re pointing at something.

14 This is a bigger problem than it seems. Of the approximately 150 million addresses in the U.S., nearly 40 million are rural and the majority of these have mail delivered to a box in a row of mailboxes not co-located with its residence. (Source: Mike Dobson / Telemapics.)

15 Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Lyft recently hired Google’s Street View VP.

16 This will be even more useful when Google starts extracting wheelchair entrance locations from Street View imagery.