Why a Flat Organizational Structure will Fail as You Grow

A few years ago, having a flat organizational structure was all the rage. Well-known companies like Zappos, Medium, and Buffer were singing its praises and writing detailed posts explaining their reasoning.

Tired of bad bosses, and corporate politics, the internet rejoiced.

On paper it sounded so great. Why do we need managers? Who needs structure? We’re all adults here, right?!?

Not so fast.

Since those big moments of press and praise, the luster and excitement for having a flat organizational structure has turned to failure and post mortems:

- Github gave up on it during public turmoil last fall.

- Buffer gave up on their flat structure as covered in cofounder Leo Widrich’s post, “What we got wrong.”

- Medium abandoned the holacracy model it previously touted because it “was getting in the way of the work.“

- Treehouse, the online training platform, returned to managers, calling the no-boss attempt “naive.”

- Zappos, the billion dollar shoe company, lost almost 1/3rd of their employees when they offered a severance package to anyone unhappy with the process.

These high profile failures and public mea culpas by many of these company’s founders has all but put the nails in the coffin for the idea of growing a company with a flat organizational structure.

Whether holacracy, or another form of #nomanagers, the pattern seems to be the same: the bigger you get, the harder it fails.

Today, we act as coroner, looking at the causes of death for flat orgs. We also guide you on what to do instead so you avoid some of the biggest problems conventional organizations face.

Why a Flat Organizational Structure Fails as You Grow (and what to do instead)

“Those who do not know history’s mistakes are doomed to repeat them.” – George Santayana, philosopher and novelist (1863-1952)

Buffer, Medium, Zappos, and others that have tried and failed to have various forms of a flat organizational structure learned hard lessons. If you understand why they failed, you are more likely to avoid them yourself, no matter your size or type of organization.

Looking at the press and blog posts around these companies provides telling insights we can all learn from.

Flat Organizational Structure Fail #1: You can’t manage everyone yourself

While some companies are very intentional in bringing in a flat organizational structure like holacracy, too often, companies fall into it.

One day, you look around and you have 15-20 employees that all report to you.

Many of your earliest hires in particular love the freedom and autonomy you’ve had since you started, and so you’re afraid to add structure that may upset them. Many left their corporate job to avoid structure and politics.

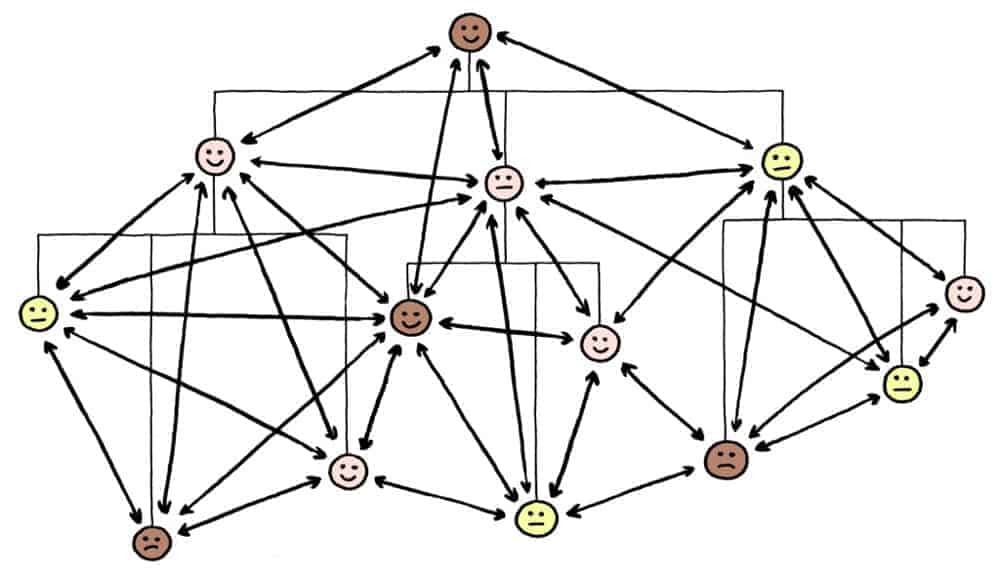

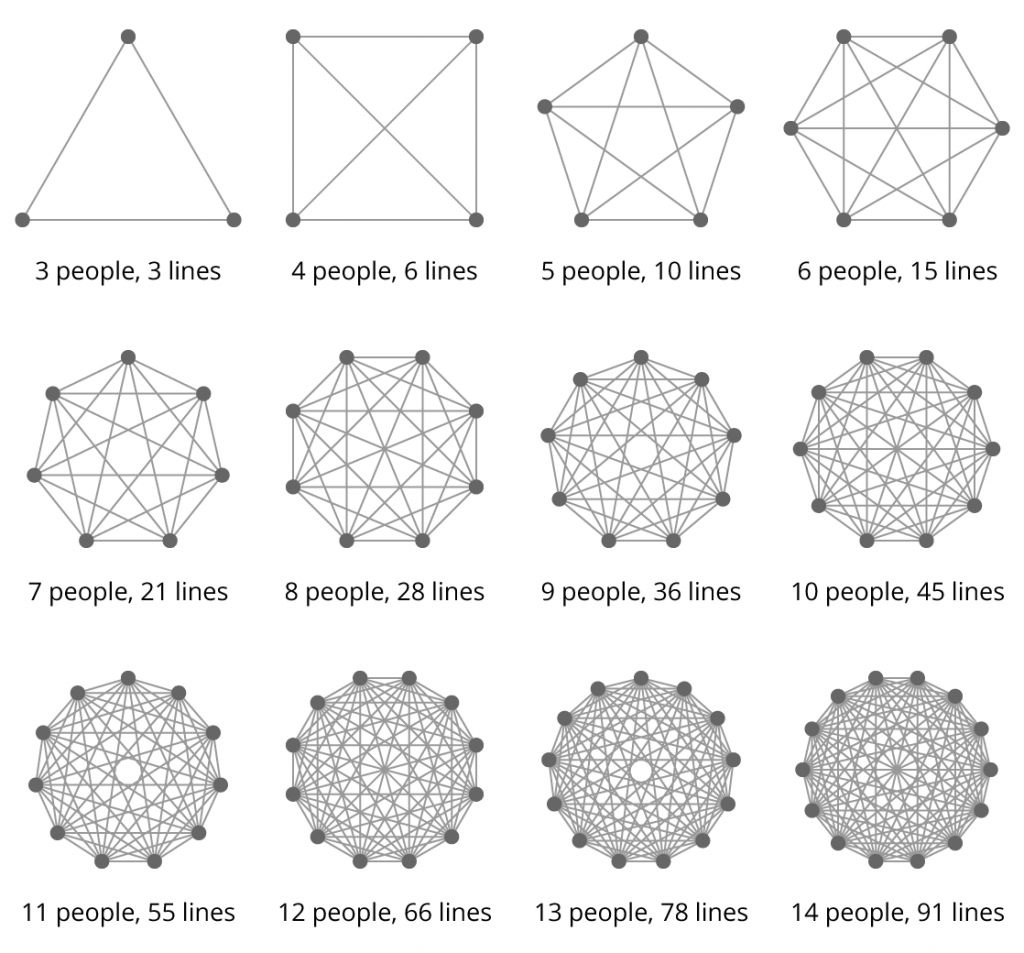

As you can see in the image above, adding more people to a group adds complexity geometrically; there is a greater tax for adding the 8th person than the 7th, 9th person versus 8th person, and so on.

Slowing yourself down.

Without structure, and managers, it is much harder to get things done, and make sure the right person has all the information they need.

When you have over 100 employees, no one knows everything going on at a level to make effective, detailed decisions. Without structure, you prevent people from specializing, and moving forward quickly.

This is exactly the problem that caused Medium to move away from holacracy as they wrote:

“Our experience was that it was difficult to coordinate efforts at scale. In the purest expression of Holacracy, every team has a goal and works autonomously to deliver the best path to serve that goal. But for larger initiatives, which require coordination across functions, it can be time-consuming and divisive to gain alignment.”

As your company grows, delegating authority is essential. Being deliberate in who you choose to lead various teams is more likely to succeed than hoping it organically happens.

Flat Organizational Structure Fail #2: Unspoken lines of communication & decision making form

In theory, a flat organizational structure is great; the best person for a given problem steps up and addresses it and everyone supports them. It allows more people to take on leadership roles, and always ensures you have the best person for a given problem.

Unfortunately, that’s not how it works in practice. As Boston-based Wistia found as they grew from 2 to 30 to over 60 people, a flat structure went from an asset to a blocker. Their CEO, Chris Savage, reflected in a blog post:

“We began to realize that by building a company with a flat org structure, we had done the exact opposite of what we had intended. We had centralized all the decision-making, and we were relying on a secret implicit structure to make progress.

Every company has a structure. If you don’t explicitly define your structure, then you are left with an implicit one, and that can stifle productivity. We had hoped that being flat would let us move faster and be more creative, but as we grew, we ended up with an unspoken hierarchy that actually slowed down our ability to execute.

…

An org chart is a map of the growing organism that is your company. If you have a clear map, it makes it easier for everyone to know how to navigate communication and decision-making, and feel more comfortable that you’re headed in the right direction.”

This is a common set of problems flat orgs face as they scale, regardless of their industry or mission.

The Tyranny of Structurelessness

American feminist Jo Freeman wrote an essay called, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” based on her experience in a 1960s women’s liberation group who tried a flat organizational structure. She reflected on the root of the problem when she wrote:

“This apparent lack of structure too often disguised an informal, unacknowledged and unaccountable leadership that was all the more pernicious because its very existence was denied.”

When you don’t have a set structure, one naturally emerges. Unfortunately, this organic structure lacks the authority and accountability officially designated leaders. Navigating this shadow hierarchy creates conflict and confusion, slowing your company down.

Flat Organizational Structure Fail #3: You miss or become overwhelmed by problems

Without hierarchy, eventually, any leader will be overwhelmed. While the general best practice is no more than 10 direct reports, in some cases, leaders have tried to have as many as 100 people all reporting up to a single person.

With no structure, the quantity of problems becomes a major issue. How do you address all the problems that come up when there are too many people coming to you? They either get ignored, or you never get enough of the right things done.

Who do you go to?

This is exactly what Google faced when they tried to get rid of their managers when they had about 400 employees. As reported in HBR, Google cofounder Larry Page learned this lesson the hard way:

“That experiment lasted only a few months: They relented when too many people went directly to Page with questions about expense reports, interpersonal conflicts, and other nitty-gritty issues.

And as the company grew, the founders soon realized that managers contributed in many other, important ways—for instance, by communicating strategy, helping employees prioritize projects, facilitating collaboration, supporting career development, and ensuring that processes and systems aligned with company goals.”

This lesson was also learned by Treehouse. Moving to a no-manager approach caused major problems as they grew:

“The no-boss approach was fine when Treehouse was a small company – it employed 61 in 2013 – but Carson said it became an obstacle for the business as Treehouse grew north of 100 workers. Projects went unfinished, Carson said, and there was no one to hold accountable.”

You can only focus on so many things at once. With a flat organization, there are many things that will be missed that a good manager would focus on.

This attention of a good manager is often even welcomed by employees. As one Google manager learned, “Engineers hate being micromanaged on the technical side, but they love being closely managed on the career side.”

Flat Organizational Structure Fail #4: You waste time re-inventing the wheel

Starting a business is hard. Scaling and growing a business is really hard.

No matter what kind of business you have, there are a never ending flurry of challenges to tackle. Why add an entire second set of challenges to the ones you already have selling your product or service?

Tod Sacerdoti, co-founder of Brightroll (acquired by Yahoo for $640 million), captures this lesson well in his post on “Non-Obvious Lessons Learned”:

“Employee management is another area where startups overthink, overwork and often fail in their attempts to be innovative.

…if you think it’s a good use of your time to try to innovate in employee on-boarding, performance feedback, quarterly reviews, promotions or weekly all hands meetings, you are mistaken at best and destroying your company at worst.

Call ten friends who work at great companies and crowd source the best practices. These best practices are widely understood and broadly implemented, and the differences are minimal or arguably irrelevant.“

When you try to create your own innovative organizational structure, you’re exposing yourself to great risk. Everything your business does is driven by it.

And when you get stuck and need advice, do you want a few small companies around the world to try to ask for help, or the wisdom of millions of companies over the last 50+ years?

There’s a reason Andy Grove’s 1980 classic High Output Management is still highly recommended; the right organizational structure with managers is a highly effective, battle tested approach.

Flat Organizational Structure Fail #5: Important decisions can become a mess

When work and decisions are self-organized, many unintended consequences can strike. One of the hardest is accountability for tough decisions that must be made like discipline, firing, and promotions.

Oculus game designer Katie Chironis has a great tweet storm that captures this challenge well:

i remember asking a Valve person once – “who fires someone at Valve?” he said, “oh, anyone has that power, it’s flat.” (c)

— 🎃 Katie Chironis 🎃 (@katiechironis) October 26, 2017

then said, ‘well, a committee would be formed and we’d discuss the firing.’ ‘who forms the committee?’ ‘well, it’s a bunch of people.’

— 🎃 Katie Chironis 🎃 (@katiechironis) October 26, 2017

the tl;dr: there is always a power heirarchy and if a company tries to sleight-of-hand you into thinking there isn’t one, be all the warier

— 🎃 Katie Chironis 🎃 (@katiechironis) October 26, 2017

Should everyone have an opinion on everything? Can they really?

Do you want to have to form a committee for every decision that needs made?

“In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.” – Yogi Berra

Yogi was right. In theory, flat organizations sound great. It’s in practice all these problems emerge.

Quartz has an excellent deep dive into the problems at Zappos, which includes this particular issue:

“Ironically, as it seeks efficiency and attempts to eliminate human emotion, Holacracy imposes layers of bureaucracy and adds unnecessary psychological weight on to employees.

Appelo quotes Bud Caddell, a management consultant who spent time inside Zappos to advise [the CEO] on how to improve the Holacracy roll out: “The average employee is already overworked and under trained; asking them to learn the management equivalent of Dungeons and Dragons on top of their workload is foolish, if not inhumane.”

Extra bureaucracy, and uncertainty on key decisions is costly overhead for every team member in a flat organizational structure. It also creates a variety of problems as described in this great Hacker News comment in the thread about Github’s move away from a flat org:

“It’s naive because good ideas are not always received well by self-interested actors, especially when you’re dealing with people of mixed experienced levels and backgrounds, as any company with more than a few employees is.

The manager’s role is to make a critical analysis of the proposal and make what is frequently a difficult choice about what will be in the organization’s long-term interest.“

Do you want to leave critical decisions to chance? Are you confident a self-organized committee will arrive at the right decision? How do you hold such a group accountable?

A flat organizational structure sounds so romantic, until it’s in use and your company is growing.

Unfortunately, the problems it causes hurts everyone’s jobs and puts your business at risk. This is exactly why you see all these founders writing about why they stopped; they had no choice and don’t want you to make the same mistakes they did.

What to do instead: Build and reward your leaders

As Robert Sutton, Stanford professor and best-selling leadership author has found in his work:

“It is impossible to find groups or organizations where all members have roughly equal status and power. Whether researchers study people, dogs, or baboons, hierarchies are evident after just minutes of observation.”

Rather than fighting this, embrace it.

Mark Templeton, CEO of Citrix, captures what’s really at the heart of the issue:

“You have to make sure you never confuse the hierarchy that you need for managing complexity with the respect that people deserve.

Because that’s where a lot of organizations go off track, confusing respect and hierarchy, and thinking that low on hierarchy means low respect; high on the hierarchy means high respect. So hierarchy is a necessary evil of managing complexity, but it in no way has anything to do with respect that is owed an individual.”

The best way to avoid the pitfalls of flat organizations, and ensure all your employees are respected, is to focus on your leaders. When you’re designing and growing your organization, be very intentional about what you want your leaders to do and not do.

Here’s a few places to start.

1) Get buy in from your skeptics

Your early employees are clearly very valuable to your company. They have experience from the beginning of the company, helped define the culture, and often receive a great deal of respect from others in your company.

Unfortunately, they’re often the ones who are also most skeptical of organizational structure. They may groan, roll their eyes, and resist setting up any form of hierarchy.

This is why you need to put in effort to get their buy in to these changes as you grow.

Camille Fournier has an excellent section in her book The Manager’s Path about exactly this.

Her advice boils down to taking the time to engage them in the problems you’re trying to solve. When you help them understand the issues you’re trying to address and can bring data, they’re more likely to accept it.

This is also exactly what Google did when they found how valuable managers are to their success:

“High-scoring managers saw less turnover on their teams than the others did—and retention was related more strongly to manager quality than to seniority, performance, tenure, or promotions. The data also showed a tight connection between managers’ quality and workers’ happiness.”

Showing this data to their engineering-driven organization helped get their buy in.

Rather than making major changes on your own, consider involving key influencers and skeptics in your company to ensure broad support.

2) Start developing leaders

If you want great leaders in your company you have to develop them. You have to set a standard that you expect your managers to reach, and teach them how to do it.

One of the biggest mistakes we see leaders make is assuming that because someone is good at their current job, that they’ll be good at a completely new job.

Going from individual contributor to manager is a huge leap for any employee you promote. Their task relevant maturity quickly goes from excellent to poor.

If you don’t coach and develop them at that moment, you’ll be setting them up to be exactly the kind of bad managers that cause people to think that a flat organizational structure is a good idea.

Teach your managers the fundamentals and choose people in your company who want to do the habits of good managers. Here’s a few places to start:

- Here are 5 qualities to look for in employees you may want to promote to management roles.

- These are the most common reasons companies fail at promoting from within.

- Here’s step by step how to help new managers at your company succeed in their new role.

Short on time to invest in developing your leaders? Then sign up for a free trial of Lighthouse, which can help your managers learn and build key habits to be great leaders.

3) Value and reward the right habits for leaders

Teaching your leaders the right habits is only the first step. Training is quickly forgotten if not put into practice.

We are all busy, so most of your employees are only going to do what’s required. If you do not measure and reward your leaders for doing the right things (like growing their people, coaching and giving feedback, having 1 on 1s, and focusing on the right things), do not expect to have great managers.

What’s measured tends to improve, and what’s ignored, is unlikely to improve on its own. This is why Google, and now many other companies, are running surveys like the Google Upward Feedback survey and ensuring all their managers are having 1 on 1s.

Also, think about the example you’re setting. Nothing signals more to your team what matters than your actions. Do you have good habits?

As an extension of that, what you measure, recognize, and reward, signals to your team what’s important. If you reward and promote good leaders, you’ll see more of them. However, if you are a poor leader that doesn’t invest in developing leaders, it’s likely your leaders will be poor as well.

Conclusion:

Scaling an organization is hard no matter how you do it. Adding the uncertainty and hidden complexity of a flat organizational structure only makes it harder.

While it may be tempting to try a wild, new org structure, don’t fall for the siren song. Your efforts are much better invested in making the best conventional organization you can.

As many of the companies and leaders we covered today revealed, you’re going to end up having to switch after a flat organizational structure has failed for you anyways.

Why not get a head start in the right direction instead?