How Much To Manage (“Management Energy Units”)

How Much To Manage (“Management Energy Units”)

Scaling the management structure of startup or scaling yourself as you progress in your career requires a careful balance of where time is spent. One of the most common discussions I have with managers and CEOs is how much time to spend and with whom when it comes to managing.

Most time management approaches focus on categorizing time by audiences such as customers, e-staff, partners, press, investors or by function such as sales, marketing, engineering. And much of the advice is rather dogmatic — spend every minute building a great product, if you’re not selling you’re not winning, etc. I think this approach tends to be too granular and much harder to manage day to day.

I have found it helpful to think about managing in terms of direction — managing up to those you are accountable/responsible to, down to those you formally manage/responsible for, or sideways to your peers across functions/teams.

Management Energy Units

Everyone from an individual contributor, first line manager, manager of managers, to big boss should spend time thinking about how management energies — or Management Energy Units, MEUs — are used and allocated. There’s a finite amount of effort one can and should put into management. How we do that depends on the role we each play on the team and also the way people we work with choose to spend their time. Correctly utilizing MEUs is critical to the smooth running of an organization. What’s a good strategy?

Most of the time when people get frustrated, either as a leader or as part of the team, it is because there is frustration with getting things done — as companies scale things slow down, decisions get gummed up, or nothing happens. Since management is literally the use of means to accomplish an end, the fix for those symptoms is in better management.

Up, Down, Sideways

Management is often thought of as an employee working for a boss, being “told” what to do and getting feedback. Boss to/from individual is one direction of management. In practice, management is at least a three dimensional effort. As Spock cautioned of one leader in ST:WOK:

He is intelligent, but not experienced. His pattern indicates two-dimensional thinking.

It is important to understand that every expenditure of MEUs can be viewed through both a positive and negative lens. This is because (a) there are good and not so good ways of getting things done and (b) there are always at least two parties involved in management and so how things are perceived depends on the direction of the MEU arrow.

So how can we think about the 3-D aspects of management:

- Up. Everyone manages up, whether CEO or the last person in the org chart. CEOs have boards, customers, partners, and more. Individuals have their direct manager of course.

- Sideways. Everyone manages sideways. Sideways is a way to express collaboration, dependencies, or just a team. Even as an individual in a 5 person startup where everyone reports to the CEO, each person needs to do their part to manage the efforts across peers. In a complex organization, your peers share a manager but might also have their own complex teams and likely totally different responsibility (sales, marketing, engineering, product,…). My experience is that great leaders tend to work with senior execs more as sideways management than boss management.

- Down. For the most part, only those who are formally managers manage down and for the most part the best organizations work to reduce the number of managers overall (balancing that with product line complexity, types of job functions, and geography). Still even as an individual you can think of managing down as it relates to how you interact with customers, early adopters, or external partners you might be tasked with working with.

Let’s look at each direction specifically, then in the next section consider how to allocate time.

Managing Down

This is the most commonly talked about form of management. MEUs in this situation are spent moving people/teams in a specific direction. At its best, this is a nuanced and elegant effort that essentially goes unnoticed.

A person who is strong at managing down often follows the pattern of the right thing happening but no one being sure who told whom to do what and when. The best execution of this type of management is generally 1×1 and based on discussion and a two-way dialog about what needs to be done and why.

A person who is strong at managing down often follows the pattern of the right thing happening but no one being sure who told whom to do what and when.

On the other hand, simply ordering (or “tasking”) someone to do something without nuance or subtlety probably isn’t the best practice for an information based organization (though it might work in a traditional command and control setting). This is because in an information based organization different information is brought to the table by each employee. So if you want to make a decision on incomplete information, just tell someone to do something — there’s a good chance you are telling someone to do something you don’t have full knowledge about.

One should be cautious of our modern tools and distributed workforce and how the written tone in email, Slack, or Jira can sound more like ordering or tasking rather than soliciting input on if something is a problem and what if any solution is needed.

There’s another dysfunction of managing down which is just asking someone to do something they are not expecting, might not agree with, or doesn’t benefit them. If you’re asking someone to do something in front of other people, then you need to be very very certain that the person will react well to being asked for that. Saying to yourself “I’m the manager and they have to react well to being asked to do this” is not likely to yield a good response. It really squeezes a person to be cornered like this. In some circles this type of “jamming” is known as spending political capital. Spend those MEUs wisely as you don’t have a lot of them.

For managers, it is a good idea to think hard about how you spend MEUs in terms of managing down and the process you use to manage down.

Managing Up

It is hard to say managing up without this being immediately viewed as a negative by everyone. As the person managing up this feels like something you have to do to please your boss, to provide them with something, or most negatively to do something you don’t think is important but your boss is asking for.

When viewed by your peer group, managing up can also be synonymous with sucking up. Managing up can also be viewed as manipulating your boss — trying to be sneaking about setting expectations in a way that allows accountability to be moved. That is if you are managing up you are doing things that don’t make sense but are specifically motivated to make your boss look good or to avoid looking bad.

There’s a time and a place for bad news (as soon as possible) and that is often the most important thing to communicate — good news travels fast, bad news needs to travel faster. The more you casually inform your manager about your work the easier all this becomes.

All of these are pretty yucky no one wants them on a team — reminds me of the famous Almost Live sketch, Ineffective Middle Management Suckups.

However, there is an important and necessary aspect of managing up which is keeping your boss informed about what you are doing and how it is going. As basic as this sounds, everyone benefits from their manager knowing what they are doing and how things are going.

Being a strong member of the team means making it easy for your manager to know what is going on. Managers do things too and it is helpful to be proactive in terms of informing your manager. There’s a time and a place for bad news (as soon as possible) and that is often the most important thing to communicate — good news travels fast, bad news needs to travel faster. The more you casually inform your manager about your work the easier all this becomes.

The dysfunction of managing up is when you are pushed to do things that you do not think are relevant to your job — in other words being asked to spend time managing up. The dreaded status report or “compiling a report for your manager”. There’s an obvious rule of thumb to follow here which is if you can’t see the benefit for work you do then you should be able to discuss why you are being asked to do it.

It is a good idea for everyone to think about managing up and how to be effective.

Managing Sideways

We don’t often think of collaboration as management, but in practice the techniques used for collaborating with others (whether across peers, function, or organizations) are essentially the same as managing. That is also why the path to being a manager is demonstrated by showing strong results in cross-team collaboration. No matter what role you have in the organization, it is pretty important to get skilled at managing sideways.

Managing sideways is all about getting alignment on the work needing to get done without the ability to make a person do something. It turns out that in practice most everything that happens in a company is managing sideways. In fact, one could argue that even if you manage someone the techniques used to make forward progress look a lot like the techniques used to manage sideways.

Managing sideways is all about communication. Managing sideways is all about an open, honest, and complete dialog. There are many ways to do a great job at managing sideways, almost all of them start from a plan — a documented plan for what to do and an execution plan for getting it done. And then build on that communication in a non-confrontational manner and transparency.

Budgeting MEU

What’s the right amount of time and energy to spend on each of these management directions?

We all need to think about this because there are only so many hours in the week. Time is the scarce resource. All the while the primary focus of an company or team are work products (code, programs, content, etc.). How much time to spend on each depends on your role in the organization. Let’s look at this through the lens of individual, first line manager, and manager of managers.

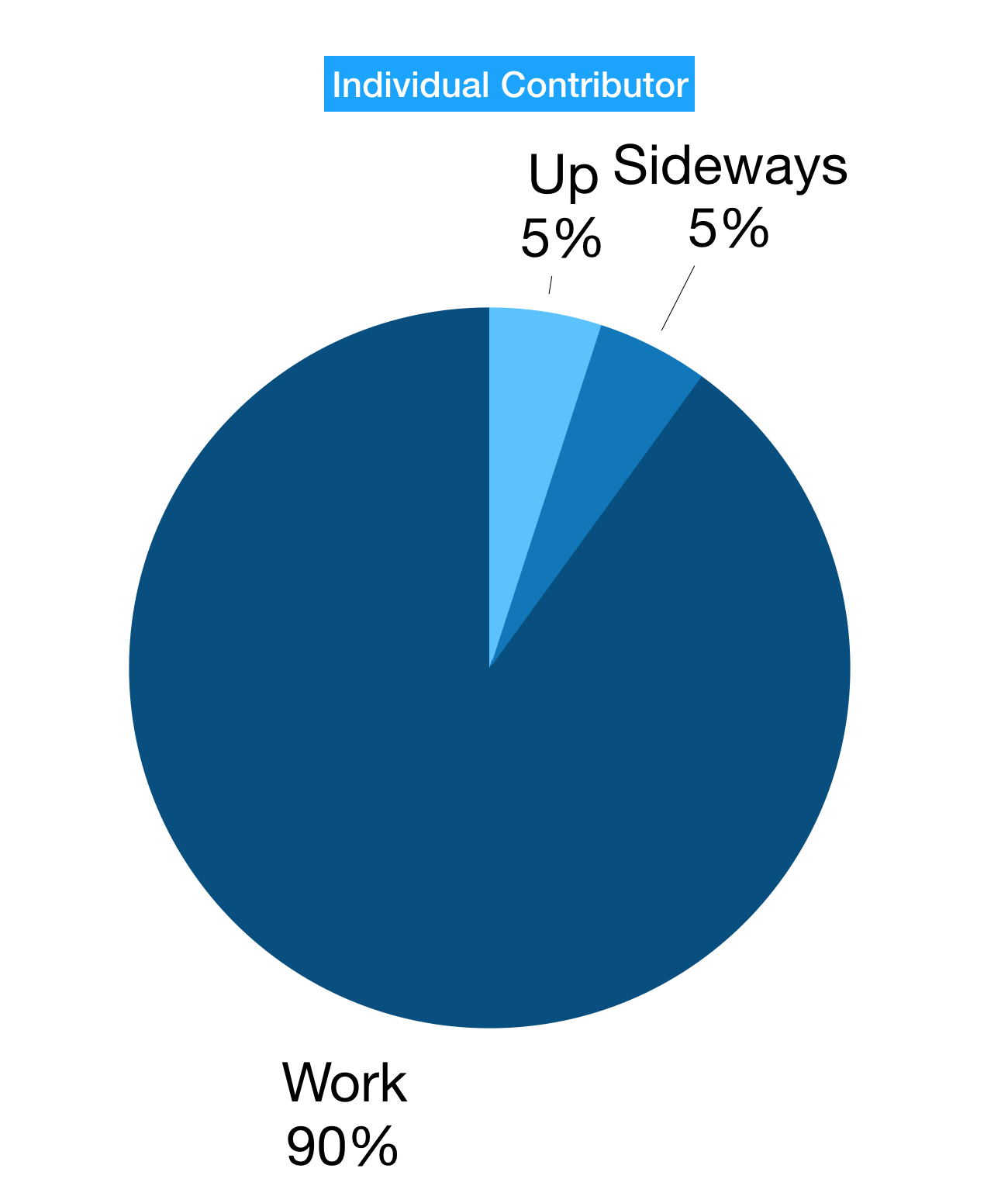

I will use conceptual pie charts — this is to illustrate the proportions of course and is not a literal time allocation tool. Keep in mind that these charts would be an aggregate over a period of time. At different times in a project you might spend a lot more time on one area than on others, but over time the average should look something like this.

Individual Contributor

The goal of any organization is for individuals to spend as much time possible doing “real” work—plain and simple and unambiguous. We tend to think of this through a blunt lens like sales people should be selling on site with customers, engineers should be writing code, and so on.

Friction and frustration occur when there are activities which distract from this.

There is, however, a very important caveat. It is possible that if you are not spending the right amount of managing time up or in peer collaboration that you are actually making counter-productive efforts. This is where there is a big difference between “getting things done” and “moving the project forward”.

As a member of the team you’re empowered to get done what the organization needs to get done. Your responsibility is to be part of deciding the overall goals for your area and the implementation of that. The management structure’s responsibility is to make sure that what we are choosing to get done makes sense — both by including people in the process and by making sure that the goals are based on bottom up planning.

The skill for an individual to master is how to effectively manage up. This is a great conversation with your manager about what is required and what works. The very best way this works is that your manager can just freely absorb the work you do without you having to package it up for your manager in some sort of status report. These are where the tools for work such as Git, Salesforce, or Hubspot are great, and managers should be looking to them rather than seeking repackaging of that information.

I wanted to share a quick anecdote on how personal style can “cross” with team culture. When I first started at Microsoft, the culture was very much the classic “testosterone based development” (which was literally what it was called). One aspect of this was that most engineers would do tons and tons of coding and do a huge commit just prior to deadline. This would frustrate a lot of people and break builds from conflicts (slowing things down!) but was viewed as the norm for star engineers. Others on the team would make more frequent incremental commits, thus sparing everyone from a giant bolus of code. That seemed like a good idea. Yet such good team behavior had a downside for that individual. To many this individual came across as making slow progress and trying to get progress credit for minor changes like new header files or refactoring files.

Of course over time we learned collectively that our culture was rewarding the poor choices made by the “10X” developers while penalizing the work of the thoughtful and planful engineers. New norms were established and the team evolved. Importantly, the visibility of progress, albeit “incremental”, reduced significantly the need for individuals to explain to their managers what they are up to and put manager minds at ease.

Since everyone needs to work with other people, there is time to do spend working with your peers — in other disciplines or on the partnerships you have to implement your work. Having a good plan means this should not be a burden during execution.

That’s all a long way of saying there is no goal to drive management efforts for individuals to zero. That’s not practical or desirable. But let’s say that a person should only spend 10% of their time managing as an individual — that includes 1:1s, team meetings, and sideways collaboration. That’s about a half day per week.

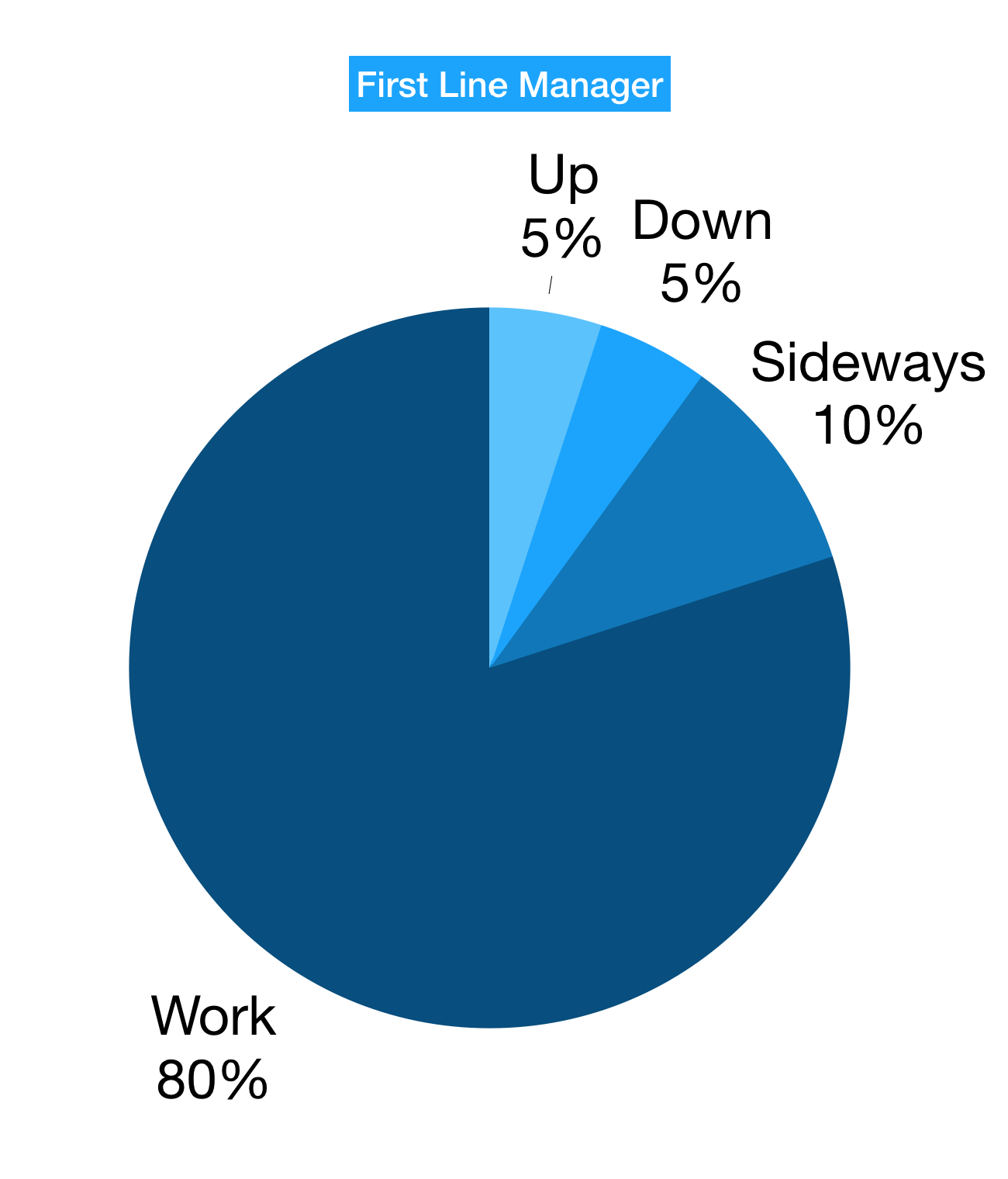

First Line Manager

Being a first line manager is a pretty special job and one of the most challenging in an organization. Generally first line managers are expected to be stellar individual contributors and to also be stellar at using a small amount of time to coordinate and amplify the work of the team they manage.

In a startup, the Series A stage usually brings with it the first set of managers for each discipline and is a time when culture and work norms are established.

In a large company, it is critical to the success of an organization and essential to the “resource allocation model” that first line managers not be “pure managers” and to contribute significantly in the same work that the people they manage do. Perhaps the first “warning sign” seen in potential hires or in growing organizations is if first line managers move too quickly to just managing all day.

In a startup, often there is the reverse problem in that the first managers don’t spend enough time managing and are entirely focused on their “old” job.

Thinking in terms of MEUs can help.

It is also important that first line managers do a great job at allocating time to employ the best techniques for creating a positive environment in terms of getting work done by the whole team. Since first line managers are supposed to be outstanding individuals, they are clearly well-versed in getting work done, managing up and managing sideways.

What is new for a first line manager is managing down. This is the thing that changes the most when you become a manager. One day you come to work and all of a sudden there are people you are responsible for helping. How you approach this is of course critical. If you view your team as there to make your job easier you are almost setting yourself up for a challenge. What you want to do is figure out how to use your managing down time to make the job easier for your reports. What can you not ask for—not what can you ask for.

You can see how this relationship can be symmetrical since if your reports are using their manage up time to figure out how to better inform you and keep you in the loop while you are using your time to make sure you are not asking for things that are not helpful to your reports then all is happy!

The best way to “manage” is to make managing part of routine conversations about getting work done. From a time allocation perspective, this means it falls in the 80% bucket and not the time allocated for formal 1:1s (which for first line managers can be 30 minutes per week per person). In general, the newer the employee is that you manage the more you want to talk to them daily or more.

That is why the most important thing to do with respect to managing down is to have routine conversations, 1:1’s, and to make sure you talk about what is working and not working for each of you in an open and honest fashion. As a first line manager the burden falls to you to demonstrate that what you are asking for in managing down is worth the effort in terms of moving the project forward and is not just about the manager.

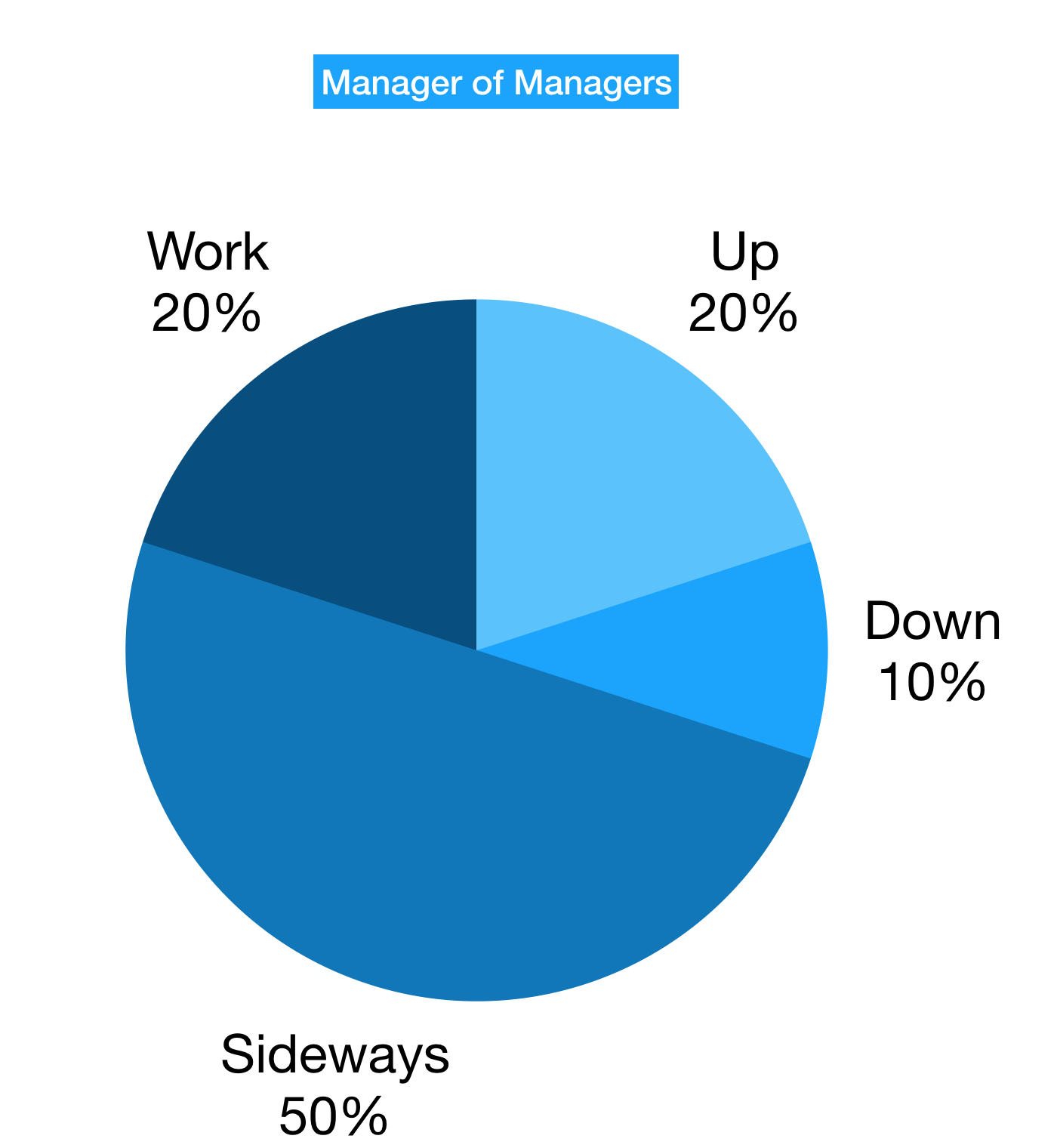

Manager of Managers / Big Boss

Most organizations should not have a lot of managers of managers. Even in the largest organizations, execs should spend a lot of energy making sure the organization is “flat”.

While this is a topic of a whole other post and a lot of other writings, it is good to keep an eye on this as a startup grows. It is quite easy to add extra management layers and not realize it. A good rule of thumb is that no more than 20% of any organization should be managers and less than 1 in 5 of those should be managers of managers. Believe it or not, at Microsoft we managed the thousands of people on both Windows and Office with these metrics.

The expectations is that managers of managers continue to do work—but the work is different though. Most of them won’t write code, marketing plans,or test plans, but they will spend a lot of energy reviewing plans.

As a manager of managers you are going to most of your time managing across the company or team. The way to think of this is that a small number of people (4%) dedicated almost entirely to managing in all directions will bring greater efficiency to a company than a larger number of people trying to do the same.

Managing in all directions effectively is difficult. The most common dysfunction in a big organization is the manager of managers acting alternatively like a router or a sieve—essentially mediating information flow.

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing a manager of managers is to make sure as one you do not panic at the feeling of “losing control” of what is going on and as a result start to push too much energy to managing down. This is really the biggest stage of growth for you as an individual and for the company.

A huge part of the work of being a manager of manager is creating the plans for the team and making sure the right people and resources are applied to those plans. Using the rhythm of execution to keep you informed, focusing on informal efforts, and 1x1s are likely to be the best tools to use to spend your down MEUs.

GTD

What does all this have to do with “getting things done”? The most iconic view of a strong employee relative to management is “get out of my way, give me the resources I need, and I will get the work done.” This always sounds great. It only works if you are a lone employee in your own company.

The reality is an organization of any size does not want to get “things” done. An organization wants to get a specific set of things done and that set of things almost always requires coordination — either the work takes more than one person or the output of one person needs to connect to the work of other people (technically, strategically, spiritually).

An organization is about multiplying your own efforts beyond what you can do on your own — mobilizing your MEUs is how you multiply your output.

So next time you are feeling down on spending effort on management (in any direction) think of how to make it more effective and fix how it is being done since that is how you get more done. A little counter-intuitive but a good way to ease your frustration and focus on the benefits of being part of a team.

Learning More

There’s a well-known and oft used training called, Power Lab, that uses “Tops, Middles, Bottoms” as roles in an organization. The concepts are very good and once you read about the power forces and dynamics you will see things differently I promise. That said, a long long time ago a bunch of Microsoft execs participated in the most extreme version of this workshop (think Survivor: Management) and together we literally broke the simulation—a long story best saved for some podcast or something.

— Steven Sinofsky (@stevesi)