When delivery is free, will ownership survive? – NewCo Shift

Cheap distribution already changed the world once. It most likely will happen again.

In the late 1990s, my father became a thief.

He would stay up late into the night in his office upstairs, his desk perched where my bed used to be. The green glow of the CRT reflecting off his forehead in the dark, he would sit nearly motionless, hour after hour watching the progress bar fill as he pirated old radio shows, books on tape, and music from the golden age of rock and roll.

Back in the early 1990s, it was not obvious that the internet would launch a global army of greying men into the world’s most tedious crime spree. It was not obvious college students and housewives and kids obsessed with Jamiroquai would join them to take down the record industry. And journalism. And video stores, encyclopedias, and travel agents.

In retrospect, we misunderstood what the internet was. In the mid 1990s, we saw the internet as communications technology, a way to send notes for work or update family about the kids. But as the internet grew and download speeds increased, it turned into something far more profound: History’s cheapest distribution technology.

Self-driving cars will bring the next great disruption in distribution. Like the internet, they will restructure not just their intended market — transportation — but every single thing they touch.

This post describes how.

Distribution is hard to write about because it is deliberately hidden from sight, buried as pipes and quietly routed through the backs of buildings. But distribution systems bring us every shirt we wear, every meal we eat, every plank of lumber that supports the houses we live in. It was a change in the technology of distribution that allowed my father to engage in petty larceny from a bedroom. It was a change in distribution that brought the record industry to its knees.

Self-driving cars will launch in 3–4 years, and immediately drop the cost of distributing objects to just a fraction of today. Distribution-by-robot has already started in China, and has the potential to herald as profound a change in society as the introduction of the car, train, or airplane — changes not seen in living memory.

And although it has been over a century since the last disruption in transport, we have a light to guide our understanding of what’s coming: The deployment of the internet. The turmoil that followed the roll-out of digital distribution — the demise of print journalism, the growth of sharing, and the end of music ownership, to name a few[1] — gives us a roadmap for understanding what may soon unfold in the world of things.

In a very short time, cheap physical distribution could carry our newly-acquired digital habits to the physical world. We could share objects. We could subscribe to stuff. We could go through life accessing every thing we desire from a mechanized, Lysol-misted cloud.

Disruption from the internet blindsided us. But this time, we have a chance to learn from history, to have a conversation about what world we’d like to build next. Prediction carries risks — and predictions involving people are the riskiest of all. Yet there is much to gain from reflecting on the disruption we just experienced, so we are not surprised to see, for example, the very concept of owning things recede into the rear-view mirror.

But we’ll return to ownership. To begin, the best way to glimpse what our future may bring is to dial back the clock a couple decades, and consider what my father and his friends did to the world of music.

In the mid-1990s, when I was living in Pasadena, California, I would walk from my student apartment through neighborhoods of stately Tudor homes to buy music at Tower Records. Tower didn’t have the best prices, but it was well-lit, with friendly staff, and stocked a copy of almost anything I needed.

It is, of course, gone now.

We did not fully respect it at the time, but Tower’s reason for existence was its selection — it was built to hold inventory. And in a world where music distribution was expensive, this was a sensible and economic thing to do.

Inventory let a customer browse for music. Inventory assured that sales closed. Inventory served lovers of pop, classical, or punk rock with equal facility.

And this is the primary function of retail today: House product, and wait for customers to arrive. Implicit in this business model is the assumption that a good’s lowest cost path to the home is for a consumer to drive, park, fetch, and return.

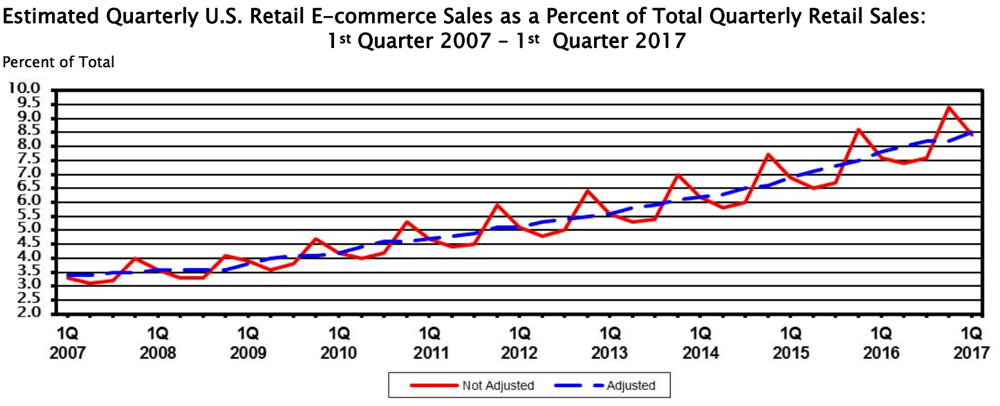

The internet created a cheaper solution. Optical fiber was the instrument of Tower’s demise, but any cheaper and faster distribution path would have sufficed; Amazon, FedEx, and UPS have steadily whittled away at the cost of distribution, and in doing so have ever so slowly chipped away at brick and mortar’s dominance.

A gallon of milk or a bag of frozen French fries can’t fit through a fiber, and even today, with Amazon’s average delivery cost of about $8,[2] makes little sense to ship from warehouse to door. But what happens when self-driving cars cut the cost of home delivery all at once to $2, or $0.50?

In a world where an electric self-driving vehicle costs less than $0.20 per mile to operate, a customer would be happy to step outside and pick produce from a market that pulls up to the door. At that price, a consumer could afford to take just a single apple, and consign the store to its next destination. Can retail survive that kind of discontinuity in distribution?

Should it?

When distribution costs fall, the advantages of inventory can be duplicated by multiple quick, small deliveries. There is no requirement to design retail around a loading bay; with cheap self-driving distribution, grocery stores could be made smaller, nestled deeper into neighborhoods (and closer to customers) without sacrificing selection. Retail could focus more on its other roles: providing a place to meet, a place to gawk (like the Apple Store), or a place for inspiration and community (like a farmer’s market). And for some goods, retail could shrink into the delivery truck itself; compress into a kiosk; or vanish entirely.

But most interestingly, the conversion to digital distribution in music didn’t just snuff out the inventory at the retail store: It dispersed the inventory at home as well.

We never really wanted to own music.

For my entire childhood, our basement held shelf after shelf of reel-to-reel tapes, recordings of a crooning Bobby Darin or Fats Domino to remind my dad of the thrill of his teenage years. But the tapes were artifacts; they were clutter that got in the way of the real goal.

What mattered was music. And when music arrived on demand, the shelves in the basement could move on.

Our apartments and houses are full of clutter, closets and cupboards full of goods sitting silently in the dark, waiting like my dad’s tapes for their shimmering moment of service. My pantry spills over with cans of tomatoes and boxes of trendy grains; yet ingredients provide no joy until I cook. My pantry exists to save myself future trips to the store. My pantry exists because distribution is expensive, and slow.

A pantry is inventory. In a world where distribution to my door is cheap, fast, and reliable, why would I need it? Why not shrink my own storage, and receive small shipments on demand instead?

It’s not just our pantries; our lives are choked with inventory. Find any collection of things, at home or at work — it almost certainly piles up because the cost of distribution is high.

A shed? Your garden tools are used only a few times per year, and if properly cared for will outlive you. Why do you store them?

Your closet? Your winter sweater is inventory, and earns no interest. Every suit or pair of shoes you own represents your savings, slowly dying.

When you follow this simple logic — when distribution costs fall, goods disperse — the conclusions surprise us, in exactly the same way that music surprised us.

The average renter has $20,000 to $30,000 in possessions. An affluent homeowner has likely spent hundreds of thousands of dollars[3] to stock his home with things which sit unused for 99.9% of their lives.

While a favorite T-shirt or a collection of shoes might inspire passion, most ownership provides no joy: We do not fondly reminisce about the extension cord in the garage, or develop an emotional connection to our colander. We carve out spaces in our homes — shelves and cabinets and closets — at a cost of over $1000 per square foot in a city like London or San Francisco, simply because there is no distribution system that could deliver a thing at the moment we need it.

So what would happen if we spent thousands of dollars not buying stuff, but grasping it only during use, and releasing it when we are done? What if distribution was cheap enough that the cost of summoning and returning things was economically sustainable? What if it was widespread enough to be quick and reliable?

The answers can be found in music. For this is, of course, the basis of Spotify’s business.

There are already startups seeking to make the closet obsolete, offering to ship you new clothing once a month, or more. There is no need to do laundry; dirty clothes are simply packed for return. This is, simply put, Spotify For Clothes.

It’s possible to build a Spotify to distribute garden tools, or wine glasses for parties, or single-purpose kitchen equipment. When we use a thing so sparingly why, exactly, do we own it? Why not subscribe to stuff instead, trying out a fun gizmo, but not make the commitment to house and care for it for the rest of our days?

There are plenty of motivations to subscribe, storing stuff ‘in the cloud’, and summoning it only when required. Just as with Spotify, we would benefit from access to a greater variety of supply, the ability to try something new, and freedom from clutter. The logic of subscription does not end with bits; the benefits of sharing do not stop in kindergarten.

Ownership is not a law of nature. It’s an artifact of distribution.

We learned with music that you don’t have to own a thing to benefit from it. You could, for instance, share.

The sharing of music surprised everyone, because upper middle class people — by which I mean most everyone who works in technology — do precious little sharing (at least in the US). Our friends, the people we feel most comfortable asking for a favor, are scattered miles across town. And getting the stuff from them — distribution — is expensive. So we buy things ourselves, perhaps borrowing a serving platter from the neighbors when visitors arrive.

But when digital distribution became cheap, behaviors changed sharply. People swapped music with strangers. We gave up ownership (full disclosure: It took a year of lobbying by my children to convince me to let go). And we found three new ways to engage with this modern concept, music and information-on-demand, that could map directly to stuff if distribution gets cheap enough.

The first was to share.

Western society has produced at least an order of magnitude more things than it actually needs; we could sustain ourselves for years, if not decades, by temporarily checking out items and returning them when we are done. This is, in its extreme form, a radical socialism of stuff, powered by cheap technology.

Of course, unlike music, physical things chip, scratch, and wear; it is not clear whether it is in the best interest of ourselves or society to release our precious possessions to the wild. But we can do great service by distributing that which we treasure least. The things we exile to the top cabinet in the kitchen or to a table at Goodwill could instead be assimilated into the world’s largest thrift shop, invoked from the cloud. The death of the estate sale could be celebrated, not mourned.

The second path we followed was to subscribe, to pursue a corporate sponsor to ensure quality, ease of use, and reliability.

It is hard for us, as individuals, to make a guess as to how many times we will use an egg slicer or a guest room towel over the course of our lives. It is even harder to estimate how long a product will last. So a logical response is to buy cheap crap, cross your fingers, and hope it doesn’t break.

But a business can integrate use over thousands of customers; they can understand which zippers are built to withstand a tug from a toddler, which dishes will survive a teenager’s casual toss across the table. Companies invest for lifetime value, not sticker price; they see things as infrastructure rather than product. Back in the good old days, goods were built to last simply because we had not learned how to build them cheaply. With shared stuff, goods will last because building cheaply makes no sense.

If ownership wanes, we would have to rethink all of our stuff, designing not just for reliability but for all aspects of a good’s life. Clothing could be constructed to be folded by robot or washed with less energy. Quality and artisanship could be rewarded more effectively if people felt they were procuring an experience with every use, rather than acquiring stuff. It is only half in jest that I tell my sixteen-year-old daughter that I’d rather she work in design than computer science, because that is where the jobs will be.

The third path, for music and all of the internet (including this blog), was to contribute.

This is the Linux model of stuff, where a person could make a bowl in a pottery class and then donate it for the betterment of humanity. Another person may feel a calling to patch a torn quilt, or retap a stripped screw hole. The low cost of digital distribution has enabled Patreon as well as Amazon, nurtured individual writers such as Tim Urban as well as conglomerates like Buzzfeed. We could build an artisanal cloud, erected on the same mix of altruism, reputation, and community as Wikipedia or StackExchange.

The cost of distribution is a barrier to giving as well as receiving. All of the unconventional business models of the internet could apply to stuff as well, if distribution becomes cheap enough.

Are we there yet? Are we even close?

I am greatly aware that all of this sounds rather like science fiction: A choreography of robotic shelf-pickers and self-driving cars combine to form a clumsy Replicator. A modern-day Captain Picard commands “Alexa: Tea. Earl Grey. Hot.” and 15–20 minutes later, a steaming pot appears at the door.

It would be slow and clunky. It would not fit on a space ship. It won’t work to summon every thing, to every place, with equal facility.

To be fair, the internet did not sweep the world instantly either: It was eight years from the first www site to the peak revenue of the music industry; a decade after the launch of Spotify for music subscription to dominate purchases. And to be fair, we don’t yet know how fast the price of distribution will fall, or what levels it will need to reach to unlock new behaviors.

But to point out that the future will not unfold all at once should not blind us to the realization that, thing by thing, our world could be transformed. Pantries refurbish to social space. Cabinets make way for art. Closets turn to bedrooms. A world of cheap distribution could be a world of fewer, better-designed things, ones that consume fewer resources, and leave more for humans.

And not only will products and apartments change, we will as well.

Consider mealtime. In the middle of the last century, distribution by truck forged a national food network, with fresh fruits and vegetables changing the way we ate. Produce and grains were selected for their ability to withstand spoilage on the journey from farm to truck to aisle to table, farmers famously breeding out rapidly-oxidized omega 3 fats in the name of shelf stability.

And now our bodies lack those omega-3s. The last great change to distribution technology altered the composition of our cells. The next is likely to as well.

Technology defines who we are as much as we define our technology.

My father never got to subscribe to Spotify, but would have been thrilled by the experience. My teenage daughter, earbuds ever-present, can’t imagine a world structured another way. A drop in the cost of distribution took away the clutter of listening, leaving just the music, and the enjoyment.

Does it make sense to stop there? Or is it, as they say, time for things to change?

[1] I am explicitly holding myself to the consumer space for this piece, to keep things tractable. But the reorganization of the software industry using new innovations like the API call can have physical correlates in manufacturing as well.

[2] Amazon’s delivery costs amount to about 10% of total goods shipped, and the average on-line order is about $80, so the average delivery charge can be seen as about $8. It’s not an exact science, and the product mix at Amazon tilts very much towards lighter, higher value goods than what we bring home in groceries.

[3] Homeowners insurance is usually sized to cover the replacement cost of possessions, at roughly 40% of the cost of the home itself. If you have a $300,000 home, then you should assume it would cost around $120,000 to replace your stuff.

Originally published at perspicacity.xyz on August 10, 2017.

Found this post useful? Kindly tap the ❤ button below! 🙂

You can also get blog posts delivered directly to your inbox using the signup above, or following my WordPress page at perspicacity.xyz. You can also follow me on LinkedIn, Facebook, or Twitter.