The Barbarians Are at Etsy’s Hand-Hewn, Responsibly Sourced Gates

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business,” the economist Milton Friedman famously wrote in 1962. And that is “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.” Those words helped establish the now pervasive idea that companies are exclusively responsible, within the limits of the law, to the people who own them. Even the most soft-hearted public-company chief executive treats the idea with a measure of respect. In March, at his final annual meeting, Starbucks Corp. CEO Howard Schultz declared that, notwithstanding his plans to hire refugees and open stores in poor neighborhoods, the company’s commitment to shareholder value remained “absolute.”

But there are exceptions. “You’re all free to hiss,” Chad Dickerson said after quoting Friedman in a speech at a corporate social responsibility conference in late 2014. Dickerson, then the 42-year-old chairman and CEO of Etsy Inc., paused for a moment, as the audience hissed and laughed. Then, for good measure, he hissed himself.

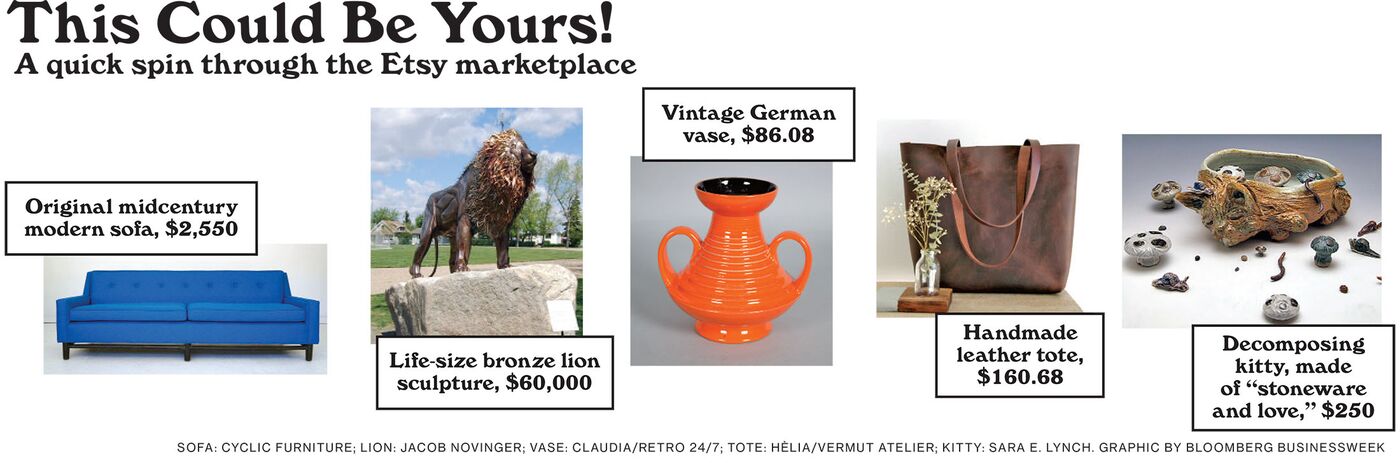

At the time of the speech, Dickerson, a former journalist with soft features and a laid-back demeanor, was preparing to take Etsy public. Founded in 2005, the Brooklyn-based online marketplace hosts 1.8 million small merchants who sell vintage and handmade goods and takes a cut of every transaction. Its sellers traffic in the one-off items usually found in antique stores and boutiques: pineapple-motif throw pillows, succulent-shaped jewelry, tote bags with birds on them. The fast-growing market is often mocked as a kind of twee EBay—TweeBay, if you will. But by early 2015 the company was selling close to $2 billion in merchandise a year and generating revenue of $196 million—figures that had more than doubled from two years earlier.

Under Dickerson’s leadership, Etsy had not only grown quickly, it had also won a reputation as an ethical company, becoming a certified B Corporation in 2012. The do-gooder seal of approval, given out by the nonprofit B Lab, requires a business to meet standards related to the environment, workers, and suppliers. Some 2,000 companies are B Corps—including Patagonia, Warby Parker, and Kickstarter—but almost all are privately held. Today there are just a handful of public B Corps; Etsy is one of only two traded on a major U.S. exchange.

Public-market B Corps are rare because investors hate them. As part of the certification, a company must reject the shareholder valuation model and, eventually, reincorporate as a “public-benefit corporation.” (To keep its B Corp seal, Etsy will have to commit to reincorporating this summer. Dickerson said in a 2016 interview that this was unlikely.) Benefit corporations are structured so managers and board members have a legal obligation to worry about more than just their fiduciary duty to shareholders. A public-benefit corporation can get sued for wasting shareholder money just like a normal public company can, but it can also be sued for being a poor steward of the environment or for failing to pay a fair wage.

When Etsy filed for an initial public offering, it limited the value of the shares retail investors could buy to $2,500 per person. The idea was to make sure shares were available to Etsy sellers and to create a shareholder base that would be sympathetic to Dickerson’s vision of a more conscientious brand of capitalism. But Dickerson also believed that big institutional investors, who make up most of its shareholder base, could be convinced that Etsy’s community focus and B Corp status weren’t incompatible with growth and profitability. “We understand the concern, but reject the premise,” he wrote in a blog post published the day of the IPO in April 2015. “Etsy’s strength as a business and community comes from its uniqueness in the world and we intend to preserve it. We don’t believe that people and profit are mutually exclusive.”

For about 24 hours, Dickerson’s comments looked prescient. In Etsy’s first day as a Nasdaq-listed company, its market value doubled, to more than $3 billion. But in the two years that followed, the stock fell 63 percent. Whatever investors thought about Dickerson’s take on capitalism, they also felt strongly about accelerating revenue growth, and they got the opposite: It fell from 44 percent in the first quarter of 2015 to 25 percent in the last quarter of 2016.

Late last year the company’s struggles caught the attention of Seth Wunder, a tech investor and hedge fund manager based in Los Angeles. In Etsy, Wunder saw a business that was fundamentally sound. A similar model had worked spectacularly well for EBay Inc., which had made money for 21 straight years—and Etsy arguably had a much better brand. It has more Instagram followers than EBay, Macy’s, and Home Depot, and more website traffic than Target. How, Wunder asked, was Etsy not making more money?

The answer, as he saw it, was that the company had been careless with its spending—Etsy’s general and administrative expenses amounted to 24 percent of total revenue. (EBay and MercadoLibre.com, the Latin American online marketplace, each spend about 10 percent of revenue on such expenses.) Etsy had been hiring like crazy, having increased its staff 55 percent since the end of 2014, and doling out all manner of perks: an elegant Brooklyn headquarters with Manhattan views, art installations, and a “breathing room,” along with salaries and benefits common at much, much more profitable tech companies. Wunder’s Black-and-White Capital began buying Etsy stock, eventually acquiring 2 percent of the company. The stake is relatively modest—Black-and-White is Etsy’s 16th-largest shareholder—but it was more than enough to launch an activist campaign. (Starboard Value LP, which successfully pushed Yahoo! Inc. to sell itself to Verizon Communications Inc. earlier this year, did so with a 1.7 percent stake.)

In March, Wunder laid out his thinking in a letter to Etsy’s board requesting a meeting about the declining stock price and “what appears to be a lack of cost discipline at the company.” A second letter, in early April, made reference to a private conversation between Wunder and Fred Wilson, in which Wilson, co-founder of Union Square Ventures and Etsy’s longest-serving board member, had shared a “frank, private opinion” on an unspecified matter.

In early May, just hours before Etsy was slated to report earnings, Wunder went public, releasing the letters on the web and publishing a press release that accused Dickerson and the board of overspending and of failing to take investors’ concerns seriously. It suggested that Etsy drastically cut costs and remove Dickerson as chairman, often a precursor to firing a CEO. It also suggested that Etsy “begin evaluating any and all strategic alternatives for creating shareholder value,” or, in English, consider selling itself.

Hours later, Etsy announced that it was laying off 80 employees—about 8 percent of its staff—and that Dickerson had been fired by the board. Among the departed were engineers, as well as employees from some of Etsy’s more far-out groups, including the “office hackers,” a group responsible for developing cool stuff for Etsy employees like a paint-by-numbers mural and a system for tracking office waste, as well as the “values aligned business” group, which is in charge of making sure that Etsy stays true to its beliefs.

The following day, at an all-hands meeting in Brooklyn, Dickerson made a short speech. He was upbeat but seemed to have been taken by surprise, according to someone who attended the meeting. Dickerson was joined by Wilson and Josh Silverman, who was introduced as the new CEO. Silverman, a former American Express Co. executive who worked at EBay in the mid-2000s and joined the Etsy board last fall, said he was hopeful about the company’s growth prospects and answered employee questions. He didn’t say whether the company would keep its B Corp status, but three people close to the situation say it’s likely Etsy will allow its certification to lapse. The company declined to comment for this story.

Current and former employees took to Twitter to voice their concerns. Jason Wong, a former engineer, urged his ex-colleagues to “fight” for “all the sellers who rely on you, for the values that Etsy stands for, for all the things you love about working there.” Privately, some employees expressed optimism, conceding that Etsy’s budgets had indeed been rather generous, but publicly the mood among the staff was funereal. “I’m not crying,” wrote Katherine Daniels, a senior engineer. “I’m just allergic to capitalism.”

Comments like this would normally seem out of place at a company that was backed by some of the largest Silicon Valley investors and had done an IPO underwritten by Goldman Sachs Group Inc., but they are fully in keeping with Etsy’s fine-tuned quirkiness. The company’s founder, Rob Kalin, started it while employed in a way that only a white male Brooklynite in his mid-20s can be: as a maker of handbuilt computers encased in wood. Kalin designed Etsy for sellers like himself, but also, as he often said, to create a sort of industrial counterrevolution, in which factory-made goods would be replaced by handmade ones, and traditional stores by person-to-person commerce. Manufacturing of any kind was banned on Etsy during its early years. These ideas held some appeal in the late 2000s, with consumers reeling from the housing crisis and reports about abuses by big companies dominating the news. “Etsy emerged right when this ethos was really peaking,” says Chirag Chotalia, a venture capitalist at DFJ who’s backed several social-minded retail startups, including the Honest Co. and Casper Sleep Inc., both of which are B Corps.

Etsy’s sellers embraced the vision. “I loved being part of a world where we supported and promoted one another,” says Meredith Jordan, a New Hampshire-based artist and retiree who sells jewelry through her Etsy shop, Wild Woman Beads. Jordan is a success—she makes about $8,000 a year selling pieces, a nice supplement to what she gets in Social Security—and a believer; she enthusiastically promoted fellow crafters on the site and bought beads for her necklaces from other Etsy merchants. When Amazon.com Inc. launched a competing platform, Handmade, in 2015 and tried to get Jordan (along with other prominent Etsy sellers) to list on the site, she said no.

But as customers discovered Etsy, the site struggled to accommodate the growth. Sellers who developed successful products were prohibited by Etsy policy from hiring employees to help them expand—that was seen as a violation of the site’s spirit. There were questions of authorship as well: If an individual craftsperson saw a successful item from another seller and put his or her own spin on it, was that an intellectual-property violation? It wasn’t clear, and Etsy was forced to adjudicate. By 2012, 16 employees, then about 7 percent of the staff, were charged with enforcing Etsy’s seller policy, which ran 14,000 words. Dickerson, who’d been a senior executive at Yahoo before replacing Kalin as CEO in 2011, attempted a less purist approach, cutting the policy down to 900 words and allowing some manufactured goods starting in 2013. Earlier this year, Etsy created a section on the site, Etsy Studio, for craft and party supplies, including mass-produced paper, glue, and balloons. The policy on handmade goods was “clarified,” as the company put it, to note that “handmade on Etsy is a spectrum.” In his final months as CEO, Dickerson also started emphasizing a push for Etsy to become an “everyday shopping destination,” in the mode of a company like Anthropologie. He said Etsy would spend more on marketing.

These changes increased revenue—Etsy brought in $365 million last year, on more than $2.8 billion in gross merchandise sales—but exacerbated tensions with sellers, who complained that the growth made it hard for truly distinctive merchandise to stand out. They felt Etsy was too lax in enforcing its rules. Popular designs are routinely copied: There are hundreds of almost identical dream-catcher earrings, more than a thousand flower crowns, and something like 7,000 “mama bear” T-shirts, many of which look like they were made not by printmakers in Peoria but by garment workers in Dhaka. Etsy is not unaware of this problem: Last year the company closed 4,500 shops for IP violations.

Jordan, the longtime seller, says the addition of mass-produced goods has “cheapened” the site. “It was heartbreaking to see such things side by side on a page with quality artisan works,” she says. Etsy, in her view, moved “away from the concept of a world marketplace and toward a worldwide Michaels craft store.” From the point of view of an Etsy seller, the comparison to Michaels, the big-box chain that sells discount framing and made-in-China crafts supplies, is damning. But on Wall Street, the Michaels Cos. is worth twice as much as Etsy. Michaels is also just the sort of company that might emerge as a “strategic alternative” for Etsy’s business.

Etsy’s headquarters in Brooklyn occupies nine floors and 200,000 square feet in an office building that was once part of the headquarters of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. It’s now owned by the Kushner family. Etsy moved here in early 2016, having spent about $40 million on a build-out. There are green walls fed by rainwater, solar panels on the roof, and numerous spaces dedicated to yoga, meditation, printmaking, and cooking, among other modes of employee self-actualization. It goes without saying that the wood is reclaimed, the paint is nontoxic, and anything that can be done by way of local sourcing or fair trade or gender neutrality is done. There’s a community loom.

And then there are the perks. Etsy offers a more generous parental leave policy than Facebook Inc. or Google Inc.—six months for both parents—along with free crafts classes and what has to be the most elaborate meal plan of any company. In “Eatsy,” as employees call the program, meals are offered twice weekly, catered by socially conscious and generally high-end restaurants. Food is composted locally as part of Etsy’s plan to send almost no waste to landfills by 2020. Until recently, when the quantity became unmanageable, food scraps were packed onto a Dutch cargo bike, which an “office ecologist” would pedal several miles to a Brooklyn farm.

Dickerson, and many of Etsy’s longtime investors, saw these flourishes as integral to the company’s appeal—the composting ritual was described in detail in its IPO filing. “Eatsy is a metaphor for how I think about many aspects of our business and our relationship to the world around us,” Dickerson wrote. “Regenerative, mindful, interdependent, community-based and fun.”

The language may sound more like something you’d expect from a Brooklyn food co-op than a global company with hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue. And yet, says Charlie O’Donnell, a venture capitalist who was at Union Square Ventures when it led the first investment in Etsy, this idealism is one of the company’s most important attributes. He credits it with allowing Etsy to recruit talented engineers away from Google and Facebook and helping it attract a distinctive crowd of buyers and sellers. “This is something a lot of investors miss and don’t understand is an asset,” he says. “It does translate into growth.”

Many Etsy employees believe this in their bones, but there are other schools of thought, especially among Etsy’s sellers, who regard the perks and the rhetoric as a distraction from the actual business of selling stuff. In its press release, Black-and-White Capital noted that Etsy’s insistence on running its own servers rather than using cloud-based services and software offered by companies such as Google and Amazon—an emphasis that was known, under Dickerson, as “code as craft”—and its “horrendous search functionality” had hampered the site’s growth, leaving it “drastically under-monetized.” It doesn’t sound like the kind of thing that would set a needlepointer’s heart afire, but some sellers applauded the letter on Etsy’s forums. “I love the critique,” one wrote. “Does this mean investors don’t appreciate the staff yoga room?” another quipped.

“A lot of sellers really couldn’t care less about Etsy’s values,” says Jason Malinak, an accountant-turned-entrepreneur who specializes in advising Etsy sellers. (He also sells how-to guides about maximizing one’s Etsy potential. His guides, which are listed on Etsy as “handmade” items, seem to stretch the definition of that word, but, then again, handmade is a spectrum.) In his view, Etsy should have focused more explicitly on helping sellers increase their revenue rather than creating, as New York magazine put it, “an extremely cozy private welfare state” for employees. Etsy sellers have long complained that the site’s search engine shows listings for newer sellers ahead of older, more established ones. This, combined with Etsy’s decision to offer add-on services for sellers, including the option to pay extra for better search placement, has led some of them to conclude that the company is trying to squeeze revenue out of its best partners. “Will Etsy return to a sales-based business model, rather than one which preferences seller services?” asked a seller, Rosemary Jones, in an online Q&A on May 11 with Silverman, the new CEO. Doing so, she argued, “would incentivize Etsy to prioritize the most relevant items in search results—rather than artificially suppressing items that fit the searcher’s needs.” Silverman called search “a key area of investment and focus” but didn’t say much else about his plans. “I’m still in the listening and learning phase,” he said.

An Etsy spokeswoman declined to make Silverman available for an interview. Black-and-White Capital declined to comment for this story, but a person familiar with the fund predicts it will continue to push for changes if Etsy doesn’t cut operating expenses further and if gross merchandise sales growth continues to slow. The person says the sale of Etsy would be only one option, but that big-box retailers would likely be interested, pointing to PetSmart Inc.’s recent purchase of Chewy.com, a six-year-old online pet food store, for $3 billion. Further complicating matters for Etsy: On May 15, TPG Capital announced that shortly after Black-and-White took its activist campaign public, it had joined the fray—it had bought a 4 percent stake and teamed up with another private equity firm, Dragoneer Investment Group. In a filing, the firms disclosed that they controlled 8 percent of the company and had contacted Etsy “to engage in discussions about strategic alternatives.”

TPG is known for buying out tech and retail companies, raising the possibility that it or some other investor could take Etsy private. That would relieve some of the growth pressure, though it would also mean giving up on the vision of a socially minded company that can thrive in the public markets.

If Etsy wants to stay independent and remain publicly traded, it will have to get bigger faster, but it’s not clear how. It’s possible that sales growth was declining because of mismanagement by Dickerson, but it’s also possible the world just doesn’t want the volume of knitting and silk-screening that Etsy’s sellers are producing. “When I think about Chad’s legacy, the fact that we’re even here talking about this is crazy,” says a longtime staffer. Etsy, the person explains, was barely a business in its early years and remained so outrageously idealistic that it seemed unlikely to succeed even as it matured. Seen this way, it’s both tragic and amazing that the company, in all its handmade, anticapitalist, pro-composting glory, became significant enough for activist investors to bicker over it.