Four days into 2017, Medium’s employees came to work and were told that one-third of them, 50 people, were fired.

They were shocked. Their adored boss, billionaire CEO Ev Williams, best known as the cofounder of Twitter, seemed to care so deeply for each of them.

But he told the world about the layoff in a blog post even before all the people who lost their jobs were informed, a former employee tells Business Insider.

Some of them found out through industry buzz that they had lost their jobs, one person told us.

“It comes down to how dysfunctional the place was,” one former employee told Business Insider. This person said that before they were let go, Medium was a “dream job.”

Medium, a blogging and publishing site, gained instant fame when it was launched in 2012 because of its well-known founder. Williams said its mission was to fix what he viewed as the broken world of journalism and create a new model.

But this latest change in its business plan – the company’s second – burnt some people so badly that industry insiders have growing doubts about Williams’ business judgment and are starting to say the company is his vanity project.

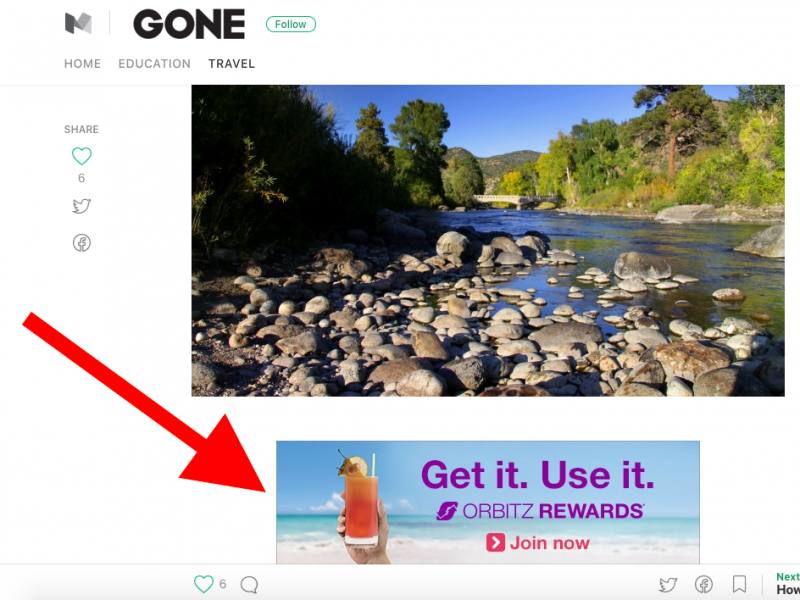

In his post announcing the layoffs, Williams said the business model Medium had been pursuing, advertisement-driven media, was to blame for “misinformation,” and that Medium would no longer sell ads or help the publishers it hosted on its site with ad revenue, and therefore it no longer needed the people it had hired to work in those areas.

He was in search of a new business model.

As with the lack of communication with employees, some advertisers weren’t told in advance about the change of plans either, and they were upset.

I did not think he would just pull the plug on publishing and start f—ing people.

And the move infuriated some of Medium’s publishers, who were not warned and had bet their livelihoods on Medium and the business model Williams was ditching. This model involved Medium cutting them a check every month – a guaranteed minimum payment – and helping them sell ads. That was over.

These people were now on their own to move to a new publishing platform if they so chose. For publications not backed by venture investments or rich owners who could afford to lose revenue, this meant a bleak future.

“I like Ev. He’s persnickety,” one publisher told Business Insider. “His ideas are interesting, and he does surprise me with his thinking. He likes people who make things, including writers. I did not think he would just pull the plug on publishing and start f—ing people. But instead he’s like, ‘Your contract is up in a while, and good luck. And I’m going to fire a bunch of people.’”

Business Insider interviewed six people from all aspects of Medium’s business, including former employees and customers. We sent Medium an exhaustive list with the information in this story. The company declined to comment, did not respond to multiple follow-up emails, and declined to make Williams available for an interview.

The people we talked to told us:

- The culture at Medium is wonderfully warm and fuzzy but also sluggish, with terrible communication. Williams is charismatic, imaginative, and brilliant in some ways, particularly around products, but he’s impetuous and clueless in others. No one is declaring Medium dead, but people in the Valley are calling it a “s—show” and a “vanity startup,” a favorite label for a disorganized startup run by a rich and famous founder.

‘Utter crap’

Medium was launched as a way for anyone to publish medium-length articles on the internet. Williams has been at this mission for decades. In 1999, before founding Twitter, he created a site called Blogger.

Although Blogger struggled financially after the internet bubble burst, it was groundbreaking for its day, and Williams sold it to Google in 2003 for an undisclosed amount (some say $20 million).

With Medium, Williams was on a mission to clean up the mess that blogging had become – and the misinformation and drivel it attracted. He hoped to cure professional journalism of these ills, too.

“The state of tech blogs is atrocious. It’s utter crap,” he told Bloomberg’s Brad Stone in 2013. “They create a culture that is superficial and fetishizing and rewarding the wrong things and reinforcing values that are self-destructive and unsustainable.” And he said he was “pessimistic about the state of media, and that’s why I want to work on this problem.”

His idea back then was an algorithm that recommended high-quality stories not based on clicks, but on how much time people spent reading them. He didn’t know in 2013 how Medium would make money, as is common for early-stage startups, but he knew he didn’t want it to be through advertising, which he viewed as one of the root causes of the mess.

Big vision, small promises

But after experimenting with business models, Medium launched an ad sales beta program in April to sell limited types of ads, such as a sponsorship of a series of articles. (For example, Marriott sponsored a series of travel articles.)

The startup had also been wooing publishers to move to Medium – to join the program and help increase Medium’s overall readership.

At an Ad Age conference in April, Williams said: “The entire point of this phase of monetization for Medium is to pay publishers. That’s what we see as our job.”

More than two dozen publishers bought into the pitch and moved to Medium, including Bill Simmons’ The Ringer, Arianna Huffington’s Thrive Global, ThinkProgress, Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls, and The Awl Network.

“To be fair, they didn’t really make promises. They framed it as an experiment,” one publisher said of Medium. “We were like, ‘This is a gamble and a weird lackey situation. It might go badly, we know that going in, and that’s fine.’ The one thing we feared was that it would go so badly [and that it might] take our business down with it.

“But we went with them because they insisted, ‘We are building a business, we do want to work with independent journalism, and we have enough time and runway to do it,’” this person said.

There was reason to believe that. Medium has raised $134 million valuing the company at $600 million, including raising a $5o million round in April when the beta program was announced. This includes investment from Williams himself, as well as Spark Capital, Andreessen Horowitz, and GV, according to Pitchbook.

But despite Williams’ public commitment, the company quickly ran into trouble fulfilling the promise.

The company had a serious discussion at its October board meeting about its future. Shortly after, the guy running its ad sales team, Joe Purzycki, resigned.

And the all-hands meeting in December did not have the usual “positive, rah-rah” tone, an employee said. Instead, Williams told the company that things were not going as planned.

A billionaire’s vanity project?

Ad sales are hard, but Medium had some early success. One of the sponsored series had generated over six digits in revenue partly because Medium could run these ads on multiple publishers’ sites, one person said. It gave the business side hope.

But that didn’t last. When the year ended, revenue had fallen short of projections, multiple people confirmed.

“We were making money with publishers. We also made money with advertising,” one person told Business Insider. “But the business we could have built, if we were to go all-in, was not going to justify Medium’s valuation. That’s a trap of venture funding. If it turns out the market you find isn’t big enough, you are in trouble.”

But there were other problems. The teams responsible for ad sales, serving publishers, and creating ad features didn’t collaborate and barely communicated, sources said. They were in their own bubbles, fighting for resources.

Williams was more concerned with other things.

“Ev is not that interested in revenue, to be honest,” one former employee said. “He’s driven by wanting to create this democratic space for people to have a voice, for the best content to rise on top. The problem that does not excite him is ‘How do I make money?’ And he has the luxury in doing that.”

Another told us: “The work there felt meaningful, but yeah, we were subject to a lot of quick changes of mind. That’s fine in the first two years when the platform is in beta and closed. But once businesses and others start to use it and depend on it, it’s not so easy to do. And that’s when some of the fracturing started.”

A publisher said that with Medium’s surprise change of plans, partners like them took big hits.

“Smaller publishers on Medium are in a bad way, and that’s the stuff I’m pissed about,” this person said. “I get it, and it’s a startup, but it’s also not, because it’s run by a f—ing billionaire. Ev’s vanity project? It has become one now, for sure.”

Nonconfrontational to a fault

All the people Business Insider spoke to agreed: They admire and like Williams. He’s a hard worker – first one in the office, last one to leave.

Employees said they loved their jobs. It wasn’t just the perks like free lunch and on-site meditation sessions; their CEO also treated them as a doting parent would.

“He’s an amazing person to work with,” an employee said. “He challenged me in ways I didn’t think were possible.”

Williams listens carefully to ideas, then helps an employee look at a situation from a new perspective. He encourages experimentation and doesn’t penalize failure.

But Williams and his right-hand strategy man, Ed Lichty, were also both described as “nonconfrontational” to a fault. They didn’t have the “hard conversations” or do ongoing course corrections to build a sustainable business, multiple people said.

Their messages to the staff were so consistently upbeat – and the startup was so well funded – that employees felt complacent, people told us. (Lichty, who has been with Medium for four of its five years, is also leaving, multiple people said. Medium declined to comment.)

Yet this was the second time they changed business models. Medium had previously toyed with being a publication itself, hiring writers and editors. Then it shuttered that effort. Employees were asked to voluntarily resign or relocate to other jobs.

Even if Williams finally gets the business model right, at this point he would have to rebuild trust and credibility in the media world.

The Netflix of publishing

The business model Williams wants to pursue next is some form of subscription, he has told people in the Valley. The idea is to become some version of the Netflix of publishing.

But Williams is also fascinated by the idea of a reader-supported business model known as patronization, one person told us.

Williams enjoys hosting dinners at his house with people in the journalism world like Katie Couric and members of Medium’s publications, one person said. At one dinner, Tim Urban, the author of the blog Wait But Why, discussed his dislike of ads.

“There are no ads on the site cause ads are gross,” Wait But Why’s support page says.

Instead, Wait But Why is supported by patronization, meaning posts are free but it asks readers to make a small monthly recurring donation using a service called Patreon. Urban has persuaded more than 4,000 people to donate a total of more than $12,000 a month. That’s enough to give him a paycheck, pay an employee, and cover some business expenses. He’s working on raising more money this way, too.

“Ev was so entranced by this idea,” one person told us. “That’s great for Tim, but it doesn’t scale. Also, it’s a hard business. Ev doesn’t like ads? Wait until he finds out what credit card processing is really like.”

And while big questions remain about how Williams would turn Medium into a credible business – not just for himself, but for its publishers and employees – his investors are still in his corner, wanting him to try.

One of them, M.G. Siegler, a journalist-turned-VC, says Williams has been successful in the first important step: building an audience for the site. “Two billion words written on Medium in the last year. 7.5 million posts during that time. 60 million monthly readers now,” Siegler wrote.

“If the company can figure out a way to do what it’s attempting to do, it’s potentially a new lease on life for some current forms of content,” Siegler said. “But more importantly, it opens up avenues for brand new types of content that might otherwise never have existed.”