Failure as a Service — Servant Leadership — Medium

Now, we have news of difficulties in the transition to the “leaderless” organizational system of Holacracy®. Apparently, Tony Hseih’s courageous call for people internally to get on board with Holacracy or get out of the company caused people, a lot of people, to… well… get out of the company. If there’s anything we hate more than bosses, it’s innovators who make us feel bad by succeeding. We prefer it when they fail.

Let me just reiterate what I’ve said before: Tony Hseih is a personal hero of mine, who founded a tremendously successful company on remarkable customer service, operational innovation, and caring about his employees.

So I take no schadenfreude in the difficulties of implementing Holacracy at Zappos. Bosses suck, and apparently the lack of bosses sucks, too. What is a person to do? Well, for me, not Holacracy or “distributed” leadership. If management is an administrative function, as I believe it to be, we’d do better to relegate it to administrative specialist role than to generalize it to being everyone’s job. I’d do the same thing with any other admin function at the company. If ordering office supplies is an admin function, we don’t suddenly train everyone on ordering office supplies. But somehow when it’s management, we start thinking differently.

So, at Fog Creek, we have bosses/managers/leaders, but those people are servant leaders. They’ve volunteered for this service and we recognize and honor that service.

So let me take a moment to drill down on the single essential service that servant leaders provide.

What… what would you say… you “do” here?

In a servant leadership organization, managers hold the organization responsible for documenting a compelling, strategically sound vision for its own future. Then, they provide the people engaged in bringing that vision to life with support and coaching. Part of coaching is to give decision-making power to the people with the most information about a problem.

Sounds simple, right? Well, it is, until someone has to make a difficult call, based on incomplete information. But how often does this happen? Well, always…. and I’ll tell you why:

As we know, the nature of business is that the easy decisions become policy, practice, part of how the business operates. So you can’t really be in business for long before all the decisions become difficult, and you can’t be in management for long before seeing these difficult decisions being escalated (read:punted) to you.

If you’re a manager in a servant leadership organization, and your people are asking you to make a decision, your first step is clear: challenge them. The first step is to say, “Why are you asking me, who knows less than any of you about this topic? Go make the decision yourselves.”

This suffices for many decisions, but even these will stop coming to you once your people realize they can’t use you to settle arguments. Then, the only decisions that bubble up to you are the ones where there’s two or more equally sound options, each with its own cost, each with its own chance of failure. Here’s what Jim Barksdale, former Netscape CEO said about these situations:

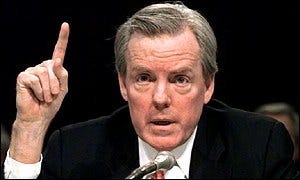

If we have data, let’s look at data. If all we have are opinions, let’s go with mine.

You can’t not love this quote. So perfect, so Promethean. It shows the perfect blend of cut-through-the-bullshit scientist and cut-through-the-bullshit CEO. It’s also structured like a joke, with setup and a great pay-off at the end.

If you imagine this mythical Barksdale guy, he probably looks like a no-nonsense anchorman with a bootbrush hairline and gravitas out the wazoo. And you’re not far off the mark.

When even the CEO is servant to the data, we see the tantalizing prospect that we might not need leaders at all. If we just measure rigorously, data and decision making become one. No bosses, no messy opinions, just science and clarity.

But what Barksdale is actually saying is that, when the right answer is unclear, it’s the job of the CEO to make a call, and take the blame if the call is wrong.

And here’s where we get to the one essential service you provide the people you manage in a servant leadership organization:

You fail for them.

Any high-school quarterback can tell you that when you win, it was the hard work of your offensive line, who gave you all that time to connect with your fast receivers. And when you lose, it’s your fault.

When the people you manage bring you a tough call, and you choose right, they get the credit. When you choose wrong, you get the blame. And it’s OK, pookie. That’s what you’re here for.

So, let’s look at this brutal calculus:

All the important decisions of the business…

minus those that can be answered with readily available data

minus those that can be answered with easily collected data

minus those that have consensus

equals the province of servant leadership.

Let’s take that province and further divide it:

All of the important decisions that no one else could make…

minus the successes, which rightly go to the team.

What’s left is a big soup of wrongness, failure, mistakes.

Do that and have it not kill you, then show up tomorrow and do it again. That’s being a servant leader. That’s what you sign up for.

When I have someone who’s willing to do this for me, I celebrate that person. I don’t eliminate the job. I don’t declare this function worthless.

I applaud companies looking at Holacracy and other self-organizing structures. They give people the essential room to experiment that’s key to innovation. But experimentation means failure. Period. If you’re not failing, you’re not learning. It can be so easy, if you’ve only seen political leadership and never really seen good servant leadership to ask “Why do we need these manager types around for anyway?”

Good leaders insure our losses and give us our gains. Any bank that took bail-out money during the financial crisis can tell you that this is a pretty sweet place to be.

When you work for a good servant leader, you’re playing with house money.

Why on earth would we give that up?