Enough With This Basic Income Bullshit

TheFamily Papers #027

By Nicolas Colin (Co-Founder & Partner) | TheFamily

The digital transition brings about many evils such as job destruction, rising inequalities, housing scarcity, and mounting political tension. These shouldn’t surprise us as the current period constitutes yet another ‘Polanyi Moment’: as long as we haven’t put in place upgraded and inclusive institutions for an increasingly digital economy, we’re condemned to live in a new Gilded Age, when most of the wealth derived from technology will be reaped by the few instead of benefiting the many.

Those evils have long been ignored, including by Entrepreneurs and venture capitalists. Even though they were visible (we have long known that technology destroys jobs), their magnitude used to be too small for the public, the press, and politicians to notice. It is only recently that a global conversation was finally initiated on the social impact of software eating the world. 2015 was the year when hundreds of online stories and magazine pages were dedicated to the fate of jobs and the future of the social state.

Not only did Silicon Valley and its satellites join this global conversation, they are now leading it. Paul Graham has written about inequalities and what he calls refragmentation (see our related paper). Other venture capitalists have taken up their pen to share their social vision (see Albert Wenger’s World After Capital). Prominent tech journalists are taking on complicated social issues (read Kim-Mai Cutler’s landmark article on the San Francisco housing market). Finally, Tim O’Reilly helped sustain the momentum by launching the long-awaited and much welcome Next:Economy summit.

One remedy always comes up: basic income. It comes up so often, in fact, that it seems to be the weapon that will defeat all those evils. A supposed miracle cure, it inspires a frenzy of declarations, works, and experiments. Y Combinator is subsidizing a research project. Prominent union leaders have endorsed the idea. Mainstream think tanks dedicate in-depth studies to the matter. Finland is about to launch a real-life experiment. Hundreds of articles are burgeoning all over the Internet — including one by Tom Streithorst which prompted me to finally take my turn and solemnly declare: enough already.

Now don’t get me wrong, I don’t hate Silicon Valley — quite the contrary, as those who know TheFamily are well aware. And I welcome discussions around basic income and its promises. But I also think that we’re getting close to the point where the conversation about risks and economic security in the digital age will finally have to get serious.

Indeed we have to fight rising inequalities, tackle economic insecurity, and imagine new social institutions for the next generations. Unfortunately the current cult of universal basic income as the solution to every social issue doesn’t help in that regard. Instead of opening up the discussion, shining a light on the concerned parties, and tracing a path toward new institutions, it focuses some of the most brilliant minds on a theoretical solution that is intellectually simplistic, socially perverse, and politically impracticable.

What’s a Social Risk?

Before everybody fell in love with basic income, the discussion surrounding the social state had effectively been going on for more than two centuries—from the Speenhamland system and the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 to the brutal and endless political fight around health insurance in the US. (See a story about passing Obamacare here, two harsh Republican memos designed to fight health insurance reform here and here, and President Obama’s views on the matter here.) Those of us who have studied this long (and violent) history are taken aback by basic income being so methodically put forward as the solution to many social problems.

Let me offer a simple framework. The social state is in effect an insurance system designed to hedge people against certain risks that for various reasons market-based insurers are unable to cover effectively. There are four traditional risks that have historically been tackled by social policy.

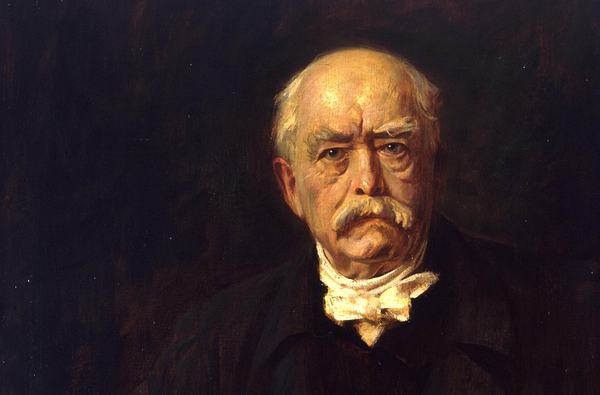

Old age is the risk of still being alive at an age when you don’t have the strength or the mental stamina to make a living anymore. The first modern social insurance regime, known as “State Socialism”, was put in place by conservative German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1883 to provide old workers with the possibility to retire with a pension.

Illness is the second risk. If your arm is broken or you have the flu (or worse), you can’t work in the factory anymore, and thus you lose your salary. On top of that, you have to pay for proper care until you’re back on your feet. Social health insurance was designed to cover that.

Child birth is a risk—it was even more a risk at a time when birth control didn’t yet exist at a large scale. Our children obviously inspire us with love and wonder, but their birth is nevertheless a social risk since it imposes additional long-term expenses that many households are unable to cover.

Unemployment, obviously, is the fourth risk. If you’re out of a job because your factory closed down or your boss fired you, you need transitional income to help you train for another job, take enough time to negotiate with the next employer, and pay the rent during the whole process.

There are two reasons why those four risks call for social state intervention. The first is their high criticality. A risk is critical if it is highly probable: for instance, most of us are bound to get old (dying young, fortunately, remains a small probability). A risk is also critical if, however improbable, it can have a devastating impact on your life: having cancer can ruin you if you don’t have health insurance; losing your job can plunge you into a devastating spiral towards poverty, etc. By definition, criticality is probability times impact.

The other reason why these risks are not well-covered on the insurance market is that they are all affected by what economists call market imperfections. Moral hazard, a well-known imperfection, “occurs when one person takes more risks because someone else bears the cost of those risks”: it plays a key role when it comes to covering the unemployment risk. Another frequent imperfection on insurance markets is adverse selection: if given the choice, an insurer will refuse to cover those who present signs of a high level of risk, thus providing insurance only to those who eventually don’t need it. Hence, for instance, the Obamacare provision that forbids insurers from refusing customers with pre-existing conditions.

The Fordist Social State

There are different ways to cover social risks. In some cases, providing a revenue is enough because, like for old age or unemployment, the stake is mostly to replace your professional income for a certain period. But in other cases, ensuring income continuity is not enough to cover the loss. Not only are you confronted with long-term inflated expenses (in the case of childbirth for instance, or chronic disease), you also need access to certain resources that can’t be provided by the market at an affordable price.

The problem of unaffordable prices is notably visible in the healthcare sector. When you’re gravely sick, you’re willing to pay almost anything to be cured because it’s a matter of life and death (or so you think). What’s more, most of us don’t know anything about medicine. This leads to the so-called price inelasticity of demand, thanks to which healthcare providers tend to raise the prices up to the point where only rich patients can afford them, thus evicting the others from the market—a situation that Obamacare is currently struggling with. For health insurance to be effective and sustainable, it is thus necessary to cap the prices and even subsidize public hospitals and other providers to ensure universal access. (This, by the way, is the reason why illness is the most complicated social risk: the social state has to deal with imperfections on both the healthcare market and the insurance market.)

The fact that it isn’t only about distributing money to individuals makes social policy extremely complex, even frustrating. More and more, it is not enough to pay citizens a monetary benefit. The social state also has to supplement the imperfect market with government-sponsored entities such as hospitals, job agencies, childcare facilities, retirement homes, social centers, etc. As a result, in the Fordist economy, governments willing to cover their citizens properly had to choose between two different evils.

On the right is the infamous voucher system. It has been widely experimented, often with negative results, in fields such as education. The principle is to provide individuals with money and let them find providers on a lightly regulated market. Vouchers often deliver poor performance. The money distributed contributes to inflating the prices as the price elasticity of supply is negative—if only because nobody’s sure that the vouchers will last (everything depends on the next round of elections). Those with lesser means, having only the voucher to spend, are thus trapped with the worst providers (or no provider at all, despite the voucher), while the richest pay on top of the vouchers to secure access to the best offer, contributing even more to inflating prices.

On the left, we find the giant social bureaucracy we are all fed up with. The quintessential bureaucratic social state is the British National Health Service (NHS). The advantage of a system such as the treasured NHS is that it guarantees everyone access to affordable and professional care providers whatever your location and your income level. The painful problem, which turned the NHS into a thorn in the side of every British government, is that in the current context of tax revolt, hatred of government, and fiscal austerity, the quality of the experience provided by the NHS can only go down, with longer waiting lines, less customized care, and ultimately a vicious circle in which everybody loses, patients as well as professionals.

Now we can see the main reason why basic income is so seductive. The Fordist social state seems to be ineffective whatever the underlying philosophy. If you pick the left-wing option (heavy bureaucracy), then the quality goes down, prompting the rich to escape the system altogether. If you pick the right-wing option (vouchers), then the prices go up, depriving the poor and even the middle class of access to affordable care. Surely there must be a better system—and we, as tech people, may have the solution.

The Devil’s Case For Basic Income

There are some convincing arguments in favor of basic income. If they weren’t good arguments, nobody would be having this conversation.

The leading argument is that there won’t be any jobs left anyway, and that meanwhile technology will bring all the costs down. Hence the bigger picture: we should all receive a fixed sum, spend it on the bare necessities made cheaper by technology, and that’s enough for the social state. (I personally don’t think that jobs will disappear, but that’s another story.)

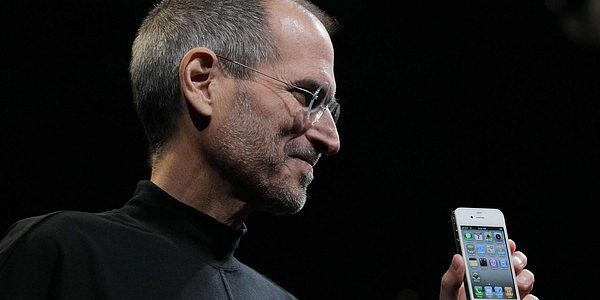

Another argument is simplicity. Here I’d like to point out what seems to confuse many: the simplicity of a product’s specifications has nothing to do with the simplicity of its design for the end user. It’s actually quite the contrary, and technology can only help in that regard. You can now build a highly complex product that provides its users with a simple, seamless experience. Nobody said that the iPhone’s technical specifications were simple; yet it is easy to use and, unlike many government programs, it provides high quality at a high scale. Indeed we’re not used to governments doing a good job at making things simpler for citizens, but believe me, it’s possible: it (only) takes capital, talent, technology, and a ruthlessly perfect execution. (Be aware that simplicity is an argument often used by government-hating conservatives — for example to support the regressive “flat tax”, which by definition does not trigger redistribution or boost demand.)

A third, even more powerful argument is continuity, otherwise known as benefit portability. Every current social benefit, considered on its own, is rather simple. What makes the system complex is the fact that throughout your life, you have to go from one type of benefit to another as you are hit by unexpected events or when you change your professional status—wage earner, freelancer, Entrepreneur, student, jobless, stay-at-home parent, pensioner. In the current state of things, using the social state is not a seamless experience: the more switches you make, the more forms you have to fill in and the more documents you have to submit.

In other words, the core problem of the social state is not that it doesn’t work. It is that it can only work by relying on a giant, rigid, insufferable bureaucracy. As it has not yet been eaten by software, the social state is still stuck in the age of paperware, in which complexity tends to weigh on the customer’s shoulders (to the delight of those who hate the very principle of government intervention).

All those arguments for basic income are perfectly valid. Yes, the social state should be simple for its citizens. It should ensure the portability of benefits. And it should take into account the fact that jobs—notably those that entail routine tasks—will probably be increasingly scarce in the near future. But all that is a lot more complicated than merely replacing existing benefits with basic income or establishing basic income on top of existing benefits—with this probable outcome: once basic income is in place, you won’t have to wait long before the rich ask that other benefits be ended because they cost too much and basic income is sufficient for supporting a social state. Whatever the outcome, at this point you will have failed at solving critical problems such as the sustainability of the pension system, tension on the housing market, and the price inelasticity of demand on the healthcare market.

The Basic Income Already Exists… In France

By the way, you’ve probably never heard of it, but basic income already exists in France—it is called the Revenu de solidarité active (“RSA”) — formerly Revenu minimum d’insertion (“RMI”). It’s a welfare benefit “aimed at people without any income who are of working age but do not have any other rights to unemployment benefits (such as contributions-based unemployment benefits).” (2.5 million people claim the RSA every year and it costs €10 billion annually, which represents less than 0.4% of the French GDP. Bear in mind that those under 25 are not eligible.)

The program is remarkable for three main reasons. First, it provides (very modest) living means for all those who are unable to work again, simply because there aren’t enough jobs (France has a 10% unemployment rate), as well as providing for those recipients who have mental health problems, need to take care of a dependent family member, live too far from potential employers, or are just discouraged or depressed. Second, it has often been blamed for providing an incentive to give up looking for a job, which is why the “RMI” was changed into the “RSA”, which, up to a certain amount, you can claim on top of a professional income (like a negative tax). Third, the claim in and of itself is complicated and intimidating. You have to fill in many papers, prove that you don’t have sufficient income or any valuable property, go through many humiliating and intrusive controls. If you want to earn (a small amount of) money without working, then you must endure it all. In most cases it is necessary to seek the help of a social worker to carry out the procedure in its entirety.

So you could argue that the “RMI/RSA” is basic income, except maybe for the paperware frictions that it inflicts on those who are eligible and that could be removed thanks to technology. Accordingly, those in favor of basic income should pay attention to the “RMI/RSA” and draw appropriate lessons: it’s not simple (at all); it has adverse economic effects; and it is widely denounced, notably on the right, as “assistance” (assistanat) that deprives those who claim the benefit from any incentive to look for a job, thus making them live off the middle class taxpayers. If you know politics, you can guess where this is going. Unfortunately, politics is not Silicon Valley’s strong suit.

The Tech Bias Against Politics

I see four reasons why Silicon Valley sees nothing but basic income as the preferred solution to our mounting social problems.

First, Entrepreneurs in general, especially when they’re young, well-educated white men from privileged backgrounds, have no reason to have any familiarity with the complicated and unattractive world of the social state. This is true in every country.

Second, there’s a myopia that is specific to the US: the social state there is designed so that only the poor, the old and the unemployed are eligible for social benefits. The fact that the US used to be the sole developed country without universal health insurance makes the US social state all the more of a riddle (even though healthcare sucks up 20% of GDP).

Third, there’s a libertarian ideological bias in Silicon Valley that seems to turn people into ignorant morons when it comes to social state-related issues. As engineers, some don’t even get the political stakes. In any case, few express any interest in government-related issues, which remain uncharted territory (even though the US government made Silicon Valley).

Fourth, even when they genuinely care about the less well-off, Entrepreneurs tend to focus too much on what they perceive as a giant inefficient bureaucratic machine rather than on the variety of life-saving benefits that this machine provides. In their eyes, because it’s supposedly so inefficient, the social bureaucracy should be swiftly replaced by a simple seamless app—and, hey, let’s call it “basic income”!

Because of those biases, all the tech people who try and imagine new forms of benefits for the digital age tend to completely disregard the most critical dimension of all: politics. Yes, there is a political dimension to the social state, and it is not pretty—just consider the ongoing fight around Obamacare. The best way to understand social state politics is to realize that the world of the social state is effectively divided into two worlds.

The first is that of social insurance, or contributions-based benefits. In the Evonomics article I mentioned above, Tom Streithorst explains that “demand is the Achilles heel of the modern economy.” Fortunately, as he reminds us,

Over the past 80 years, we have solved the problem of demand in three very different ways. The first is war… The second, during the post war Golden Age, was rising salaries… In our most recent era, from 1982 until the financial crisis, the engine of economic expansion was ever increasing levels of private debt.

This incomplete list reveals, once again, an American bias. War, rising salaries and household debt (what Colin Crouch calls “Privatized Keynesianism”) may have played a key role in supporting demand in the past, especially in the US. Yet they’re only one part of the picture when it comes to supporting household consumption! There is also the entire system of the social state, mostly consisting in social insurance, which represents no less than 19.2% of GDP in the US, 21.7% in the UK, 25.9% in Germany and even 30.1% in Denmark, one of the most redistributive social states in the world (see OECD social protection figures of 2014).

So it’s not as if there was nothing to support demand on an ongoing basis. The social state, notably social health insurance and pensions, effectively complements household income with social benefits and subsidized services. It transfers money to the many, letting them consume more, or it spares them from the obligation of saving more, thus freeing a substantial part of their professional income for additional consumption. If that is not a massive permanent boost of demand, I don’t know what is. Indeed, it is widely documented that mitigating risks for individuals through social insurance sustains economic growth, supports small businesses, enhances individual freedom, and makes entrepreneurship thrive.

Politically, social insurance programs are extremely resilient. Paradoxical though it may seem, recipients who are blinded by their hate of government often don’t realize that the social insurance programs they enjoy are operated by the government. Just read that article “Keep Your Government Hands Off My Government Programs!” about what Prof. Suzanne Mettler of Cornell University has dubbed the “submerged state”.

There’s actually a second world of the social state, that of what the Americans call welfare. Welfare is not about social insurance providing contributions-based benefits to middle class people. It’s about aiming benefits at the poorest people, those confronted by economic problems whose gravity you likely can’t even fathom, sometimes aggravated by mental health problems, crime-ridden surroundings, and a lack of basic public services such as healthcare, transportation, and education.

Because it benefits mostly the poor, the very existence of welfare has become a powerful argument for conservative politicians seeking to polarize the electorate. You may remember that Ronald Reagan, as a presidential candidate, made great profit out of denouncing what he called “welfare queens”. It’s fair to say that basic income, if implemented, would endure the same political fate as welfare in general: “We, the rich, don’t need that basic income. So why not aim it only on the poor, so as to lower our taxes… and then denounce them as welfare queens?”. (You can read this backstory article about the real-life “welfare queen”.)

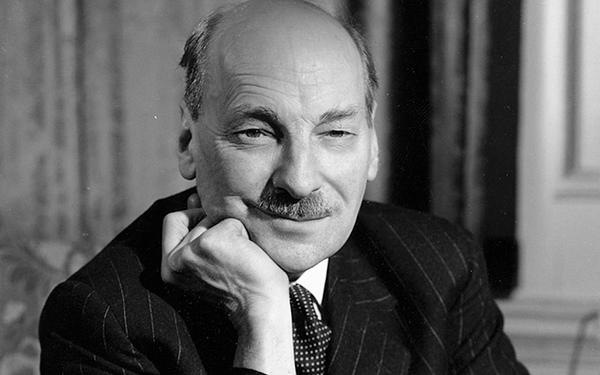

Speaking of which, a historic speech by Olof Palme, the late Swedish Social-Democratic Prime Minister, is worth quoting at length to help you grasp how tough the politics of the social state has been through the ages—and how much basic income, unlike social insurance, would be vulnerable to conservative critics:

Conservatives attack the very idea of [universal social insurance]. Not only do they dislike it from a general ideological point of view, but they also justify their opinion with economic arguments. In times of economic difficulty, they believe, the efforts of the community should be directed only toward the weakest groups in society — the very poor.

However, if society’s efforts are focused only on its weakest members through selective social policies largely based on “means-tests,” taxpayers come to think in terms of “we” and “they”. “We” — the better-off wage earners and the middle class — have to pay to the state, but get nothing in return.

The ground is thus prepared for the disintegration of social solidarity; which in turn encourages tax revolts. The fact is that it is not the weight of the tax burden that causes such revolts, but rather the feeling among taxpayers that they do not get anything for their money. People who derive some benefit from a welfare system are its greatest supporters and therefore pay taxes without feeling exploited.

An efficient and stable welfare state must be based on universal social programs, such as health insurance, pensions, and child-support allowances-programs that are directed to all citizens. Official “poverty lines” or “means-tests” would not have to define “the poor” (which would minimize the need for bureaucratic controls). At the same time, people in difficult financial circumstances would not have to put up with the degrading classification of “poor.” And because they would have the same rights as others to universal social services, they would enjoy services of a much higher standard — services that would be acceptable to the rich. Moreover, universal programs would help eliminate the “poverty trap,” in which the poor are discouraged from increasing their earnings since to do so decreases their benefits.

The Long and Dangerous Path Toward a New Social State

It’s not as if basic income was the only option on the table. Indeed it is easy to design and describe what social state institutions we should build to make the digital economy more sustainable and more inclusive. Portable benefits, for instance, are a crucial feature of the social state of the future, because career paths will be more and more intermittent and ridden by constant turnarounds and lane shifts. We also need to create new social insurance regimes to cover risks that are specific to the digital economy, like that of not being able to find affordable housing in the urban areas where more and more jobs are located.

But having the idea, or even advocating for it, is not enough to create a durable and lasting institution. What it takes to build lasting institutions is a long and painful fight. For instance, we owe the current social state to the labor movement, which fought for more than a century to force both employers and governments to hedge workers against critical risks such as illness and unemployment. The key players in that fighting game were not the intellectuals who wrote books and spoke in conferences. It wasn’t innovative Entrepreneurs, either, who built the modern social state. We’re speaking of union leaders and activists who organized against powerful adverse forces, established a balance of power with employers, and sacrificed everything for this long quest — including, in some cases, their own lives.

What the labor movement demanded was not that the government preserve the old social order. It demanded a radical effort in innovation—the building of radically new institutions. Because the Fordist economy was so new and exposed individuals to unprecedented risks, radical imagination was instrumental in establishing the modern social state—and to force this imagination effort, the labor movement’s pressure was necessary.

So it takes a very long time to build social institutions. In France, between the creation of the first fraternal benefit societies (sociétés de secours mutuel) right after the 1789 Revolution and the building of the universal social state after World War II, we had to wait… a century and a half! Because this is how institutions are built, through polarization: it takes a movement of people willing to fight for a big idea over the course of decades.

This is yet another reason why I’m skeptical about basic income: I simply don’t see the movement behind it. It’s intellectually seductive, a lot of people like the idea, but I’ve never met anyone for whom basic income is literally a personal question of life and death.

The question may no longer be one of workers versus employers. It’s probable that unions as we know them are a thing of the past. Maybe the middle class of the digital age will be a class of Internet users instead of a class of factory workers. It is also certain that every country has its own history that will shape the power fight around social institutions, paths that will make new developments very different from one nation to another. But a fight is needed to build institutions, and I still don’t see today’s equivalents of workers and employers in the hypothetical fight around basic income.

Conclusion

There are so many priorities when it comes to the social state, priorities that are more pressing than basic income. Here are seven key questions:

- What is the best social system in a more entrepreneurial society? Obviously it should make it easier to switch from one position to another and to hold multiple positions at the same time without any complex institutional burdens. It also should harness the power of entrepreneurship to improve the cost effectiveness of social benefits and the care they provide access to.

- Are there risks that have become less critical in the digital economy? I think it is fair to say that being unqualified is less of a risk today, in an age of ever-evolving technology, constant professional switching, and commoditized education resources on platforms such as YouTube.

- Conversely, are there risks that have become more critical (more probable or more impactful)? Housing comes to mind, as the digital economy tends to concentrate jobs in big cities. Can the social state help people find affordable housing where the jobs are? (By the way, neither healthcare nor housing, both imperfection-ridden markets, would be made more affordable by basic income.)

- Will jobs really disappear? The reports of the the death of work are greatly exaggerated, and there are still obstacles that could—indeed should—be brought down to free up job creation: bridging the culture gap between Fordist workers and tech companies; easing the tension on the housing market; removing the obsolete regulations that prevent job creation where technology could make it flourish.

- Can Entrepreneurs help in mitigating social risks? It’s fair to say that technology can contribute to correcting some of the market imperfections that rendered the social state necessary. But we have to reflect on how technology can help, support Entrepreneurs… and upgrade those obsolete regulations (again).

- What’s the best form of state intervention? Here’s a scoop: it’s universal coverage. Actually, Silicon Valley people, a bit more support for a better, simpler Obamacare would have been appropriate in that regard. Uber CEO Travis Kalanick actually made supportive declarations here, and Tim O’Reilly has written an inspiring piece about portable benefits here. But we didn’t hear much from the others—I suppose they were too busy discussing basic income.

- How can you redesign the system to remove frictions and reduce gaps as workers go throughout more volatile professional lives? In the entrepreneurial society, income volatility creates a wide gap between a social state designed for factory wage earners and the needs of today’s workers in the digital economy. Designing a seamless social state experience should become a political priority for future elected officials.

Basic income is to the social state what the flat tax is to the tax system. It flatters the engineering mind with its apparent simplicity. But in fact it is impossible to implement; it’s also politically suicidal; nobody’s ready to die for it; and even if it existed, it would probably trigger extraordinary political tension and the highest level of inequality in modern Western history.

So enough already. Grow up now, study history, and then join the liberal politicians and union activists (and some Entrepreneurs) who, while you’re playing around with that simplistic idea, are waging political battles and trying hard to imagine a new social state for the digital age.

Further Readings

Here are some of the most relevant articles among those linked in the text above:

- Olof Palme, “Employment and Welfare”, The 1984 Jerry Wurf Memorial Lecture, Harvard Law School, 1984.

- Tony Blair, “Speech to the Fabian Society on Public Services”, The Guardian, June 2003.

- Jacob Hacker, “The New Economic Insecurity — And What Can Be Done About It”, Harvard Law and Economics Review, 2007.

- Frank Luntz, “The Language of Healthcare 2009”, Memo, 2009.

- Colin Crouch, “Privatised Keynesianism: An Unacknowledged Policy Regime”, The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, August 2009. [Paywall]

- Jonathan Cohn, “How They Did It: The inside account of health care reform’s triumph”, The New Republic, May 2010.

- Kevin Drum, “Why Screwing Unions Screws the Entire Middle Class”, Mother Jones, February 2011.

- Matt Bai, “What Steve Jobs Understood That Our Politicians Don’t”, The New York Times, October 2011.

- Daron Acemoglu, “Success and Failure of Nations: Institutional Bottlenecks”, Zeuthen Lectures—MIT, May 2012.

- Josh Marshall, “The 1993 Kristol Memo on Defeating Health Care Reform”, Talking Points Memo, September 2013.

- James Surowiecki, “The Business End of Obamacare”, The New Yorker, October 2013.

- Franklin Foer, “Obamacare’s Threat to Liberalism”, The New Republic, November 2013.

- Jason Furman, “Six Economic Benefits of the Affordable Care Act”, The White House, February 2014.

- Kim-Mai Cutler, “How Burrowling Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained)”, Techcrunch, April 2014.

- Sara Horowitz, “America, Say Goodbye to the Era of Big Work”, The Los Angeles Times, August 2014.

- Adam Davidson, “Welcome To The Failure Age!”, The New York Times, November 2014.

- Noam Scheiber, “Uber’s Travis Kalanick Supports Obamacare. Now He Needs to Support a Tax Hike for the Uber-Rich”, The New Republic, December 2014.

- Nicolas Colin & Bruno Palier, “The Next Safety Net”, Foreign Affairs, June 2015.

- Tim O’Reilly, “Workers In A World Of Continuous Partial Employment”, What’s the Future of Work?, August 2015.

- Nick Grossman & Elizabeth Woyke, Serving Workers in the Gig Economy, Emerging Resources for the On-Demand Workforce, O’Reilly, October 2015.

- Nicolas Colin, “Another 100 Days: A Digital New Deal For Workers”, TheFamily Papers, October 2015.

- Nicolas Colin, “A Valley Divided: Do Startups Widen the Inequality Gap?”, TheFamily Papers, February 2016.

- Nicolas Colin, “Brexit: Doom, or Europe’s Polanyi Moment?”, TheFamily Papers, June 2016.

- Shelby Clark, “Friends with (Portable) Benefits: Shaping a New System with Lessons from Existing Models”, What’s the Future of Work?, June 2016.

- Barack Obama, “United States Health Care Reform: Progress to Date and Next Steps”, Journal of American Medical Association, July 2016.

- George Lowery, “Many clamor for government cuts, not realizing they’re beneficiaries”, Cornell Chronic, September 2016.

- Steve Roth, “Economists Agree: Democratic Presidents are Better at Making Us Rich. Eight Reasons Why”, Evonomics, September 2016.

- Will Wilkinson, “The freedom lover’s case for the welfare state”, Vox, September 2016.

And a few books:

- Michael J. Graetz, True Security: Rethinking American Social Insurance, Yale University Press, September 1999.

- Jacob Hacker, The Great Risk Shift: The New Economic Insecurity and the Decline of the American Dream, Oxford University Press, January 2008 (revised edition).

- Daron Acemoglu & James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty, Profile Books, February 2013.

(This is an issue of TheFamily Papers, a series which covers various areas such as entrepreneurship, strategy, finance, and policy. Thanks to Oussama Ammar, Kyle Hall, Laetitia Vitaud.)