The first rule of pricing is: you do not talk about pricing — Fluxx Studio Notes

The first rule of pricing is: you do not talk about pricing

I’ve been slightly obsessed about pricing since 2010. Before joining Fluxx, I was part of the team that changed the price of The Times digital edition from this:

To this:

Introducing what inevitably became know as “The Times Paywall” or “Rupert’s Pathetic Paywall” inspired a powerful reaction, with plenty of headlines like this one:

Even Gordon Brown — then Prime Minister and fighting wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — took time out to share his views on pricing strategy. “People have got used to getting content without having to pay,” he said. “There’s a whole sort of element of communication that’s got to be free.”

In the end, of course, it turned out that charging people money for a product they enjoyed wasn’t a terrible way to do business.

Prices are interesting because they inspire such strong emotions. Responding to price is hard-wired into our brains. When we see something expensive, we know immediately — without thinking — that it isn’t for us.

That can trigger a whole range of powerful #feelings; envy, anger, admiration, disappointment, lust, disgust, hatred, excitement. It’s a potent brew.

The opposite is also true. When we see a mountain of tea lights in IKEA with a sign saying “Glimma 100 pack $3.99,” only one human response is possible. “Ooh, that’s a lot of tea lights. We probably need some tea lights, don’t we? I’ll just put those in my yellow bag.”

It’s not a conscious decision, but an animal response to a pricing signal.

At other times, our response to pricing is absurdly complicated, tangled and self-obsessed.

Ordering wine is a social, psychological and economic roller coaster. In France, they draw huge excel spreadsheets onto the walls of their restaurants.

When they’re not discussing philosophy or plotting affairs, the customers engage with these arbitrarily sorted spreadsheets to buy wine.

You can’t buy the first wine on the list, because you’ll feel like an ignorant cheapskate.

So you look at the second wine. But, as a sophisticated Medium-reader, you’re well aware that the second wine on the list is the most popular, so the restaurateur will ensure it is also the most profitable.

You don’t want to be suckered into buying the most profitable wine on the list, so you trick the restaurant by actually buying a more expensive wine.

It’s a minefield.

Prices are a shortcut to our most sensitive emotional responses.

The smirking face of price sensitivity is, of course, Martin Shkreli.

Martin pushes every pricing button.

He bought a $9,000 bottle of wine, and tweeted the label.

He bought the only copy of Wu Tang Clan’s album “Once Upon a Time in Shaolin” for $2m, then said “I’ll probably never even hear it. I just thought it would be funny to keep it from people.”

Most famously, he raised the price of a life-saving drug from $13.50 to $750 per tablet.

People had strong emotional reactions to this pricing decision.

(Interesting pieces on Martin Shkreli here and here.)

Pricing strategy is a huge part of many businesses, but — in the world of product and service design — it’s relatively rarely discussed. There was no panel at SXSW 2016 discussing pricing strategy.

Instead, we tend to admire simple, universal pricing models.

Netflix is £5.99 a month for anything you want to watch. It’s simple, clear and transparent.

Except…

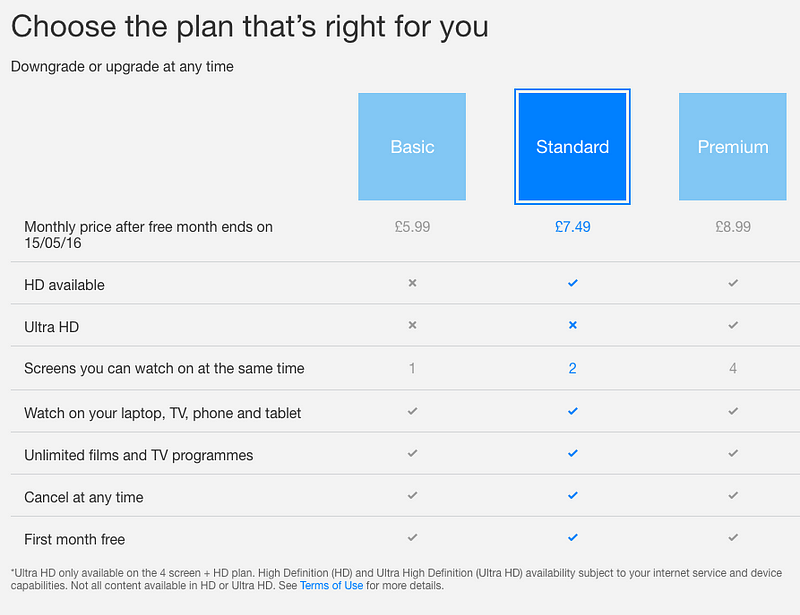

Netflix doesn’t have simple pricing anymore. It has a range of prices, from £5.99 for one person to £8.99 for four people simultaneously streaming HD video.

I don’t think anyone at Netflix expects people to actually pay £8.99 for a house full of people glued to their screens. But the £8.99 price makes the £7.49 price seem more credible. With 70m subscribers, it’s worth trying.

(The full story of Netflix pricing is in this great article by Derek Thompson, which inspired this piece.)

The importance of price to a company should be obvious. At The Times, we realised that converting customers who paid £8/week for the printed newspaper into customers paying £2/week for the digital edition (often after paying Apple £500 for an iPad on which to read the edition) wasn’t great business.

So — over two years — we gradually raised the price for those original customers to £6/week. At that price, we could be genuinely agnostic. We didn’t mind if a customer was digital or analogue; the contribution was the same. Of the original core customers regularly paying £2/week, we only lost around 10% during the price rises (many other customers came and went during that time, but for loyal customers the alternative was an £8/week print habit.)

The first rule of pricing is that you don’t talk about pricing.

It’s tempting to talk to customers about price.

Your customers — real or potential — will certainly have views about prices that they are keen to share.

Ignore them.

“It is not your customer’s job to set pricing. An optimal price is one that is accepted but not without some initial resistance” says Ash Mauyra explains in this great piece.

It is almost impossible to predict how a customer will react to a particular price by asking them. That’s because they don’t know how they will react.

They have no idea.

“Are you in the market for tea lights on this trip to IKEA?” you might ask. “No” They might say. Or “Yes”. Neither is a useful signal, because they don’t have a clue.

There’s one easy way to find out what customers think about prices. By selling them things.

The second rule of pricing is that you don’t think about pricing

As human beings find it almost impossible to think rationally around pricing. Because of this, as human beings, our own thoughts about pricing are likely to be almost useless.

When Turing Pharmaceutical raised the price of Daraprim from $13.50 to $750, they could have seen a 98.1% drop in sales — and still made more money.

When The Times introduced a paywall, the number of people looking at their digital service dropped by 98.7% (from 22m to around 300,000), yet the switch was a huge financial success.

Those kind of shifts are hard to make sense of rationally — so the flood of emotional reactions takes over.

The third rule of pricing is that experiments are the only way to make sense of it all

One classic pricing experiment was conducted in early ’80s by Joel Huber and Christopher Puto at Duke University in North Carolina.

Their paper, Adding Asymmetrically Dominated Alternatives, Violations of Regularity and the Similarity Hypothesis, outlines the experiments they did to understand how college kids buy beer (and televisions, cars, restaurants, lottery tickets, and film).

The results of their experiment are still obvious almost every time you buy something online.

They started with two types of beer; cheap and expensive:

70% chose the more expensive variety.

Next, they added a decoy cheap beer:

Remarkably, none of the students chose the cheap beer, but it’s presence on the shelf distorted the entire market, pulling the centre of pricing gravity downwards.

Finally, they introduced a premium beer:

Which had the opposite effect; skewing the entire market upwards, and significantly improving the revenue from the original experiment.

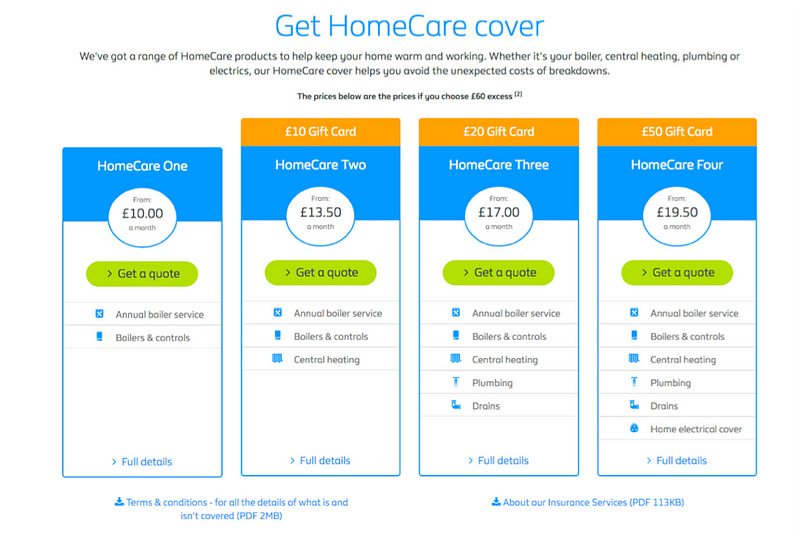

The lesson has been learned, and ‘Good, Better, Best’ pricing strategies are everywhere, from Slack:

To British Gas:

The lesson isn’t that you must have three prices, but that searching for one perfect price is likely to be less effective than finding a sensible range of prices.

It’s reminiscent of Malcolm Gladwell’s story of the futility of searching for the perfect spaghetti sauce — where the punchline is “Prego turned to Howard, and they said, ‘You’re telling me that one third of Americans crave extra-chunky spaghetti sauce and yet no one is servicing their needs?’ And he said ‘Yes!’” .

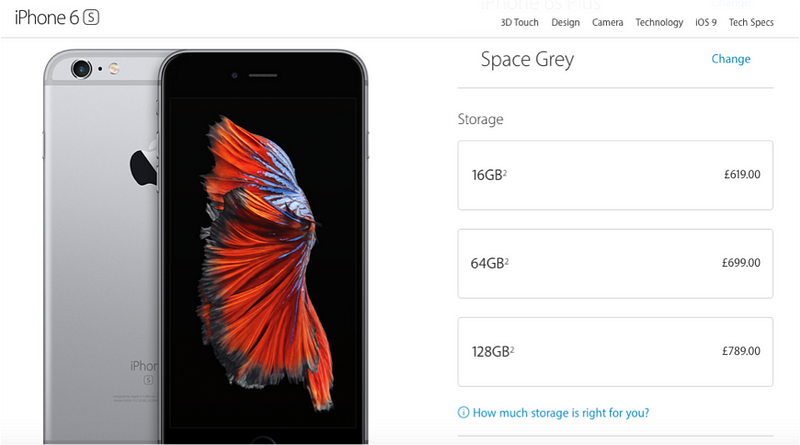

Apple have fully embraced Good, Better Best pricing, building layers of recursive GBB into their product line. First you chose your phone…

Then you choose your memory:

Is $1.60 a good price for an extra GB of memory on your phone? It’s hard to tell.

People can’t tell you what they think about pricing, because they don’t think about pricing. They feel it.

A couple of years ago, Fluxx had a client with a huge customer base paying relatively small recurring payments. They asked us to help them think about membership and loyalty schemes.

One idea was to create a premium loyalty scheme, where customers would pay a little extra each month for access to rewards.

This raised a few obvious questions; Would anyone pay? How much would they pay? What rewards would they pay for?

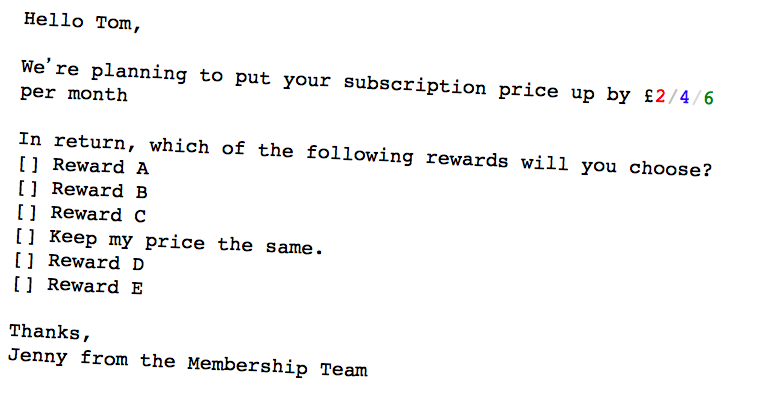

Over a few days, we rolled out a simple experiment. We sent a note like this to a sample of customers:

The idea was to write an email that felt real, not one that felt like a survey. We weren’t asking customers what they thought about a price, but how they’d personally react to a change that was coming. The email went down pretty well, with a 10% response rate, and the results were startling.

51% of customers who were offered rewards for £2 accepted the offer. In most cases, this would nearly double their monthly spend.

37% accepted at £4, and 31% accepted at £6, potentially almost tripling the amount they spent with the company.

Considering that one £6 customer would contribute the same as three £2 customers, the results were very encouraging.

With this one simple experiment, the conversation shifted from “Would anyone really pay for this?” to “I wonder what we could offer for £8/month?”

Price is the crudest, and most subtle, message you can send about your product, so it’s worth getting it right.

Running experiments is the best way to achieve that.

This is a version of a talk given at the first Experiments in Design Meetup in London in April 2016. Signup and come to the next one.

Tom Whitwell is Senior Consultant at Fluxx, a company that uses experiments to understand customers, helping clients to build better products. We work with organisations such as Lloyds Bank, Royal Society of Arts, the Parliamentary Digital Service and William Hill.

If you enjoyed this, you might enjoy “31 Things We Learned in March 2016”