Can we be both makers and managers? — The Startup — Medium

Can we be both makers and managers?

How we spend our days is ultimately how we spend our lives

While we all wish we could spend our days creating and doing meaningful work, real life (aka busy work) has a funny way of derailing us.

The urgent tasks that should’ve taken half an hour take half the day. We end up spending more of our time managing than we ever do making.

It’s depressing. I know. I face this struggle on a daily basis.

Each week, everyone at Crew sends an update to the rest of the team about what they’ve been working on. While this is a great way to stay connected when you’re part of a remote team, week after week I find myself looking back through my to-do lists and asking ‘what did I actually make?’

The urgent tasks of managing other people and projects often takes over the time I set aside to create. I live in Slack and email, reacting to every single ping and notification like Maslov’s poor little pups.

Years ago, essayist, programmer, and venture capitalist Paul Graham looked at this exact issue and proposed that there are two very different ways of scheduling your work day:

“The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals… When you use time that way, it’s merely a practical problem to meet with someone. Find an open slot in your schedule, book them, and you’re done.

But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.”

Unfortunately, most of us sit somewhere in the middle. Sure there are pure makers and pure managers, but those of us who work for ourselves as creatives and entrepreneurs need to be both.

We need to carve time into our day to both manage and make. To plan and create.

So, when you’re forced to divide your time between two vastly different tasks, how do you ensure that each gets the proper attention?

Respect your time to make

Take a look at your schedule right now. What does it say? Is it filled with appointments and meetings? Little reminders to do small tasks? Or are there deep swaths of time dedicated to making and building?

Your schedule is an inside look into what you find most valuable.

The manager lives and dies by their schedule with each task compartmentalized into successive 1-hour blocks. Time can’t go over because there’s always someone else waiting on you. One kink in the chain and the whole engine stops moving.

On the flip side, the schedule and the todo list don’t work for the maker. There is no way to say that this article or that project will take 2 hours, because you never know until you’re deep in the throes of it. And who would give up that beautiful state of flow because of a self-imposed deadline?

Whichever mode you’re in, it’s important to respect the time you’re giving.

One of the easiest ways to do this when you’re making is to practice heads down work. Turn off all notifications, get rid of as many distractions as possible and zone in on what you’re working on.

As opposed to the manager who is ruled by the schedule, heads down means ignoring everything outside the task at hand and making it happen.

It’s acting, instead of reacting.

This means giving yourself permission to say ‘no’ when you’re in maker mode — not only to meetings and work related events, but to other social events as well.

Stephen J. Dubner, co-author of Freakonomics, talks about how when he’s writing a book he goes into full-blown makers schedule:

“…when the time comes to write, I disappear. I reply to as few e-mails as possible, rarely answer the telephone, and try to turn down every invitation that isn’t vital. When I fail to turn something down I inevitably regret it, and I am guessing the people who invited me regret it as well, for I am distracted and cranky.”

This heads down time doesn’t have to be for months at a time, however. It can be as simple as a few hours every single day committed to distraction free creation.

The time may seem insignificant at first, but it’s important to remember that there’s power in chipping away at projects. As Gretchen Rubin, author of The Happiness Project, explains:

“We tend to overestimate what we can do in a short period, and underestimate what we can do over a long period.”

Maintaining and respecting your maker time can be more important than firing on all cylinders for 18 hours straight.

Set up systems, not just schedules

When you’re building your working habits there are two things to consider: your schedule and your systems.

Think of your system as being the structure beneath your schedule. It’s the repeatable process of each day or week that helps you commit to consistently making.

If your systems are your skin and bones, then your schedule is your wardrobe — no matter what you choose to wear each day it has to conform to the shape of your body.

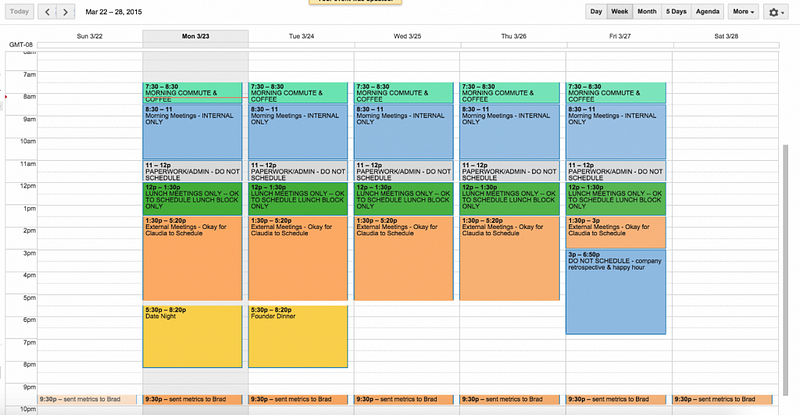

As a coder-turned-CEO, Mattermark CEO Danielle Morrill had to transition from a schedule full of maker time to one filled with manager time. Her answer was to set up an underlying timbebox structure to her calendar, meaning that every day had a similar flow to it.

By scheduling blocks of time for creating and for managing, you’ll always know what mode to be in and when someone comes to you with a meeting request, you can fit it in a time where you know you’ll be in managing mode instead of breaking up your creative work flow.

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” — Aristotle.

A schedule puts you at the whim of others; a system makes your time your choice.

Divide (and conquer) your tasks

It’s been proven time and time again that none of us can successfully multitask. And trying to switch between making and managing has a huge drain on our cognitive energy.

While having a system will help you block out times, utilizing that time to either make or manage will make you less likely to feel guilty about ignoring the other task.

One of my favourite examples is Crew CEO Mikael Cho, who practices ‘admin Tuesdays’ — where all of his meetings, management tasks, and admin work is completed in one day.

Similarly, if you’re trying to write or work on a project, grouping tasks together helps you brain settle into a certain ‘working mode’.

As bestselling writer and designer Paul Jarvis explains:

“The longer you can focus on a single type of task, the faster you can get it done. So grouping all the writing I have to do into a morning means I can write 5–6 articles in one fell swoop. Perfect. Or I’ll spend a whole day programming websites for clients, which gets my brain into ‘code mode’.”

While this works for short-term goals, you can also group larger tasks together so that you always know what you’re working on next.

This is what writer and artist Austin Kleon calls ‘chain smoking’:

“Instead of taking a break at the end of a project and worrying about what’s next, we use the end of one project to light up the next one.”

Work with your energy, not against it

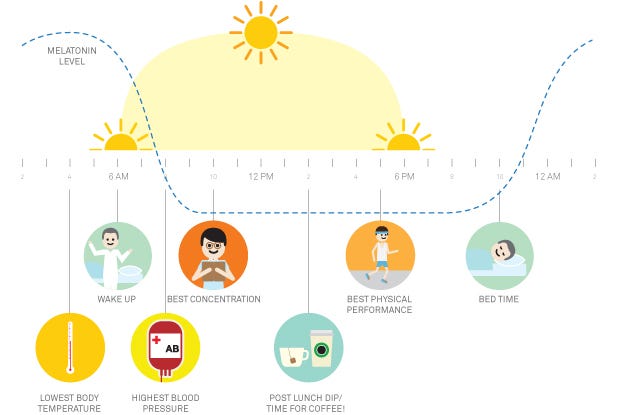

There’s a huge body of research that has demonstrated how our energy levels have a natural ebb and flow throughout the day. These are called Circadian rhythms and despite our best efforts to be 100% on, 100% of the time, fighting against these rhythms is about as productive as yelling at the ocean to stop it from coming in.

Typically, once the workday has begun it takes a few hours to get into peak work mode (around 11am-1pm), which then sharply declines around 3pm before returning for a few hours before and after 6pm.

(There are, of course, individual variances, but surprisingly most of us follow the same rhythm.)

Willpower and decision making are limited resources. So if your natural energy flow is to be more alert in the morning, using up that time to answer emails, have basic meetings, and do other less intensive tasks is a waste.

Instead, schedule your work around your own daily rhythm, using your peak hours to do the tasks that require the most concentration and focus.

Build rituals as well as routines

In the end, all anyone really wants is to develop a routine that allows us to do your best work, day after day.

But this is no small task. It’s no wonder we’ve become culturally obsessed with the routines of successful artists and creatives.

‘Routine porn’ makes us think that creating comes down to just following a few simple steps. That emulation will yield the same results. And while routine may help us decide when to work on a project, creative work requires something more than blocked off time. It requires ritual — a set of habits that put us into the right mode for creating.

However, as Brainpicking’s founder Maria Popova explains, routine and ritual really are two sides to the same coin:

“While routine aims to make the chaos of everyday life more containable and controllable, ritual aims to imbue the mundane with an element of the magical.”

A good life calls for a balance of the two — order and chaos, discipline and freedom, the mundane and the magical.

When we look at balancing our own lives, it’s the time spent managing that needs routine, while creative work requires ritual.

For designer Sarah Foleske, this means keeping and revisiting tear sheets while news anchor Pat Kieran takes a nap (every day). Hell, Beethoven had to count out precisely 60 beans for his morning coffee before starting to work.

Whatever the ritual is, once you know it, you’ll be able to use it to push yourself into creation mode.

Respect your ritual, and the time it takes to put yourself into the right frame of mind for creative work. Once you’re there, the time investment for switching back to managing will be more than you’re willing to give up.

Switching from maker to manager and back again is hard on all of us.

There’s usually a reason that we’re more drawn to creative work or to working and managing people. The two are rarely, if ever, easy things to bring together.

“There are no shortage of good days. It is good lives that are hard to come by.” — Annie Dillard

But spend a bit of time setting up your rituals and routines, respecting your need to do both, and committing to schedules and systems that give you both time to manage and to make and you’ll be in a place to not only have good, productive, and creative days, but a meaningful life.

Need inspiration to start making?

Makers is a new podcast and interview series by our team at Crew that looks at the unexpected life moments that have inspired today’s most influential and experimental makers. Listen to the first 2 episodes now on iTunes.