Only Insurgents Survive: Preparing for the Robot Apocalypse

The Bad News

You are going to be out of business 10 years from now. And if by then your business is not either bankrupt or being sold for parts, you will wish that it was.

Apple is not remarkable because they are the world’s most valuable company, but because they‘ve spent over 35 years relentlessly fighting a “lost cause.”

If you run an established, successful, and mature, large scale business where competition is the core logic of your strategy, I can assure you of the inevitability of this. And do you know what is going to kill your business? You are.

Insurgents and robots are coming to eat your business model and you aren’t ready for the war they are bringing to your doorstep (in fact, I can hear them knocking your door down right now).

RUN!

Life During Wartime

Almost no one is prepared for the arrival of this war, in part, because it has become real so suddenly. Think of the immediate and absolute shift in reality that happened on 11 September 2001.

Like the “war on terror,” this war is one of indefinite and amorphous enemies. It calls for a new kind of awareness and readiness that we could analogize to putting a country on a war footing.

In his powerful memoir of building a billion dollar company, now venture capital partner, Ben Horowitz, distinguishes between what he calls peacetime and wartime CEOs. One of the hardest things Horowitz recounts in The Hard Thing About Hard Things, was that “[the] transition [from] peacetime and wartime require[s] radically different management styles.”

“In peacetime, leaders must maximize and broaden the current opportunity. As a result, peacetime leaders employ techniques to encourage broad-based creativity and contribution across a diverse set of possible objectives. In wartime, by contrast, the company typically has a single bullet in the chamber and must, at all costs, hit the target. The company’s survival in wartime depends upon strict adherence and alignment to the mission.” — Ben Horowitz

Insurgents and Robots

Insurgents and Robots, Oh My!

‘Clever metaphors, he uses’, sure, ‘but I know better’. ‘No such bogeymen are coming for my business’, you reassure yourself.

So let me give examples.

What is an insurgent in this war of uncertain times? My favorite example is Craigslist. This “company” since its founding in 1995, almost single-handedly destroyed billions of dollars in newspaper revenues, attacking the castle keep business model of classified advertising. What the newspaper industry eventually discovered, though far too late, was that there is no way to compete with free. But free ads were only the opening gambit of Craigslist’s assault. What turned Craigslist from a scrappy rebel into an architecture for insurgency was its platform. What it made available to millions was a free ad publishing platform, for which people would eventually find myriad unimagined uses, including the opening salvos in a new war launched by a little upstart founded by a group of “mostly harmless” designers, called AirBnB.

The Matrix and Terminator films are neither parables nor prophecies, but optimistically imagine a future in which human beings resist the inevitability of losing control of a world of our own making.

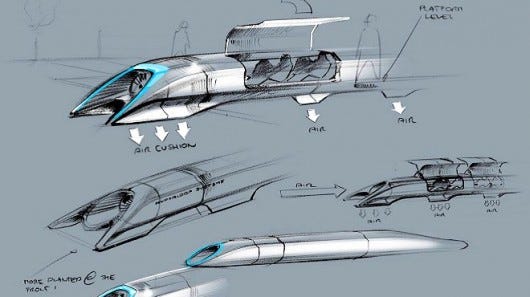

If you want an example of a robot, you should think about a now virtually antique business model called a bookstore. Amazon, everybody knows, started off as an online bookseller. But what Amazon really does is create radical new efficiencies in the consumer value chain. It has now not only obsolesced a growing number of bricks and mortar retailing empires, but is now quickly rewriting the rules of the last mile in retailing: shipping. Flying drones and autonomous delivery vehicles, whether Amazon’s or someone else’s, will likely soon topple another couple of billion dollar businesses.

Conventionally competitive businesses cannot compete with these insurgents and robots. The reason why is not obvious. Because while many incumbents think that it is Craigslist, AirBnB and Amazon are the enemy, they fail to realize that the insurgencies these platforms have given rise to are actually driven by the masses of people who are sick of the past and who are voting with their feet (or mouse clicks) to usher in the triumphal arrival of the future.

You Can’t Compete With the Future

What will almost certainly guarantee the demise of your business is remaining committed to competition as a strategy. You cannot, by definition, compete with insurgents and robots, because they are simply the harbingers of inevitability. Uber may be the insurgent force in the emerging transportation wars, but fighting them is irrelevant. The truly transformative power they have unleashed are the millions of Uber riders worldwide who simply won’t allow taxi and limo businesses or local governments to turn back the clock. The future is coming whether you like it or not.

What makes things more complicated still is that the future is not singular. It is plural, it is accelerating and it is exponential. In their book The Second Machine Age, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee make the case that we are living in a time characterized by an escalating pace of change, driven by a host of forces. At the core of their argument is the idea that change has become exponential: and that as this tendency progresses, the effects of change become more and more unpredictable. Such change produces an intractable kind of uncertainty, ushering in a state of persistent volatility which is not a problem to be solved, but a fundamentally new condition of reality. The American military started using the term VUCA in the 1990s to characterize the emergence of this new reality: volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous.

In 2010, Roger Martin wrote about how the US Army was adopting elements of design thinking into the core text of Army doctrine, the Army Operations Field Manual. This reference text is meant to guide commanders in the field on how to shape and manage both strategy and tactics in the theater of a conflict. The importance of this development, by implication, was that if the US military was betting on design thinking, that the water was safe enough for corporate America to drink.

What is the more profound lesson, though, is to be drawn from the reason the Army was drawn to design in the first place. Strategists within and without the Joint Forces command were coming to realize and face that the war on terror had drawn them into a conflict in which they could no longer compete. They realized that fighting the enemy required a strategy that was radically different from the conventions of modern battlefield combat, and that conventional warfighting was quickly becoming irrelevant. How do you fight an enemy that is as intangible as a ghost was a question that had troubled the man we have come to call Lawrence of Arabia:

“suppose we were an influence (as we might be), an idea, a thing invulnerable, intangible, without front or back, drifting about like a gas? Armies were like plants, immobile as a whole, firm-rooted, nourished through long stems to the head, we might be a vapor, blowing where we listed. Our kingdoms lay in each man’s mind, as we wanted nothing material to live on, so perhaps we offered nothing material to the killing. It seemed a regular soldier might be helpless without a target.” — Evolution of a Revolt (1920), T.E. Lawrence

This is just the problem that competitive businesses now face in confronting the vaporous enemies of disruption. There is no target, nothing to shoot at, they simply cannot kill the future that is coming. So, either you can choose to believe that they are not coming for you and your business OR you can embrace the only real alternative that remains.

You can do what the Army decided to do. You can innovate.

Innovative vs. Competitive

Competition is a zero-sum, finite game. Someone wins. Everyone else loses. This is not open to debate. This is the reality of competition. The game has rules, players and a score. Winning is defined by scoring more points that anyone else.

In any competitive business, market or industry, there is a leader. In important, large, and lucrative markets, there are second and third place positions which are lucrative enough to be desirable. Coca Cola is, and has long been, the leading drinks company in the world. Pepsi is second. You may think that Pepsi is not a loser, but you must agree that they are playing Coca Cola’s game.

Companies like Apple, Google and Amazon, on the other hand, do not have competitors. They are not playing someone else’ game, but instead choose to write their own rules. Peter Thiel explains this fact by describing these companies with an old word. He calls them, monopolies.

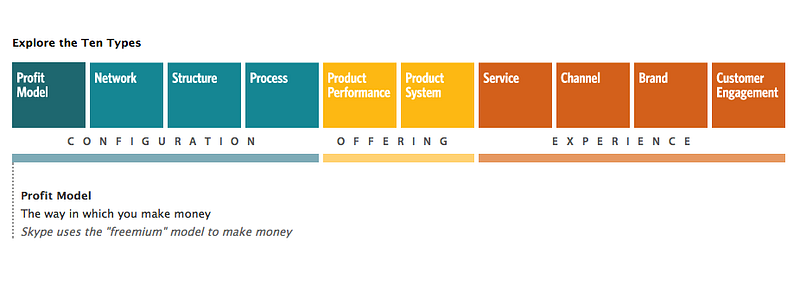

But there are two things that this word fails to capture about these companies. One, that they are fundamentally driven by the logic of innovation rather than the logic of competition. And, two, that their continuing success depends on either insurgency or robots. In other words, they are either going to war with the status quo on an ongoing basis or they are developing robots (automation, computer controlled machine power, algorithmic computation and machine learning) that eat jobs.

Marc Andreessen was kind to those who fear these forces when he said that he doesn’t think that robots will eat all the jobs. But that should be cold comfort to those who are facing the realities of a world in which insurgents and robots are everywhere and multiplying. What Andreessen is fundamentally right about, even though he doesn’t say it explicitly, is that resistance to the future that the insurgents and robots are bringing is futile. And the investment strategy of his venture capital firm, Andreessen Horowitz, is as loud an argument as anyone should need that the smart money is betting on those who innovate.

Of course start up entrepreneurship is one path, and an important one, to creating transformative innovation. But it is innovativeness itself that we must cultivate. And this requires the development of habits of adaptability. This is why the lean start-up movement has had so much traction. Fundamentally, it is a gospel of trial and error, feedback and learning, for building an adaptive system. This evolutionary theme is echoed in the manifesto that serves as the North Star of the investment strategy of the Founders Fund:

it makes no sense to shackle a company to the Procrustean bed of its original business model. Businesses really do evolve over time and changing models in the early years is anything but a sign of weakness. PayPal went through five different business models before arriving at one that worked. We do not expect that the first business model for a company will be the final or best business model and do not see evolution as a negative. The most powerful minds are the ones that can be changed. — from What Happened to the Future

The Evolutionary Enterprise

Evolution in business is not driven by simply inventing new products, improving service or developing a new business model. Focusing on these things alone will NOT save you from the insurgents and the robots. But if you are not doing all of these things (and more) with the white hot intensity of the insurgents or the relentless, tireless and unstoppable force of the robots, then you are already one of the walking dead, you just don’t have enough of a brain left to realize it.

One of the most damaging effects of the exuberant culture of Silicon Valley (and the so-called Californian ideology) and the hype around start ups is the sense of powerlessness and defeat they have created in large, value-creating companies. Yet, there are a growing number of examples of established, mature, companies that are creating new sources of growth and expansion. What’s remarkable is that they are not simply building on their traditional business models, but innovating, challenging and in some cases replacing their legacy model.

Those that believe that massive companies are incapable of evolution ought to try to explain the successes of IBM, GE, Apple, Tata, and Li & Fung. And newer companies like Google, Amazon, Alibaba and Tesla. What characterizes all of these companies is that they are innovating rather than competing. They are focused on making the future rather than on defending the past. What best characterizes these evolutionary actors is not their ability to compete, but their persistence.

Persistence Innovation

Persistence hunting is a mode of human predator behavior adapted for our upright posture, which confers an advantage for our superior endurance over other animals. The concept of persistence can help illuminate the core advantage of the evolutionary enterprise. Persistence innovation does not name a process or methodical approach to innovation, but rather describes its value to the organization.

Persistence provides us with a powerful analogy to innovation as a discipline. In the persistence hunt it is not simply that we outlast a “competitor” in the food chain, using exhaustion as a strategy to beat their superior size and strength, but that we upset the expected hierarchy of advantage. While others go left, following the well worn and proven path. The innovators go right.

The analogy of innovation to a physical practice like climbing is compelling because both reward the disciplined practitioner. Lucas sees the route that everyone else has left unexplored because in a flash he realizes that he doesn’t need to follow the rule they are all constrained by, he can write his own rules.

And now, the good news: you can do this too. The best kept secret of innovation is that there is no secret. Innovators draw on something we all share, a natural ability to see beyond the limitations of the present by projecting ourselves into the future. Successful innovators can connect to this ability at will and under enormous pressure, because they have disciplined themselves to expand into the volatility of the environment rather than to recoil from it.

Making the shift from the dominate or perish mindset of the competitive organization to the more expansive and trail blazing consciousness of the innovator requires a relentless and unforgiving discipline. The fanaticism of insurgents is only successful when supported by conditioning, training and the development of a constant state of readiness. Without a willingness to “burn the boats,” however, you may as well not set out on the journey to innovate at all. Because orienting your organization toward innovation is not the same a creating or improving a single product. The commitment to becoming a company that drives growth and improvement by pursuing the path of persistent innovation is not a temporary measure but an absolute and permanent change in what your company is at its core.

Innovation is hard. It is not for the weak. It is the work of the hard corps: the toughest, strongest, most disciplined people in the organization. I have been working with a team to create an approach that will prepare innovators to face the challenges of the VUCA world. Think of it as a kind of training camp for business and design insurgents, those who aren’t ready to surrender to the robot overlords just yet. We call it HARDCORPS: a discipline for those ready to practice Persistence Innovation. The future in which your business is taken from you by either robots or insurgents is not inevitable. But you’ll have to learn to fight them.

Join the resistance now.