On Leadership. Fatherhood. And Managing Different Personalities

What does it mean to be a leader?

It’s relatively easier to answer that question when you’re a founder & CEO and have total control over hiring & firing. If your company is successful and valuable people generally do what you ask. It can sometimes create confusion about whether or not you’re truly a great leader or whether people feel they must just follow your orders. A truer measure is when you must persuade purely through logic, performance, respect, effort, guidance and empathy.

I learned this in college. I often tell people I learned more about how to become an entrepreneur by being president of my fraternity than any college course I ever took or any paid job I ever had. As president I had to convince a bunch of college-age students to pay dues, turn up at weekly meetings, manage budgets, doing community service and avoid the kind of behavior that might make your organization defunct. Ordering people around was an impossibility and meetings consisted of back-benchers second-guessing every hard choice I had to make.

I learned about leadership again in my first job out of school. I was hired by Andersen Consulting in 1991 during the midst of a recession. Gen X’ers are pretty well profiled but I can tell you we were all grateful just to have jobs and pay our bills. There wasn’t any such thing as skipping the line or raising money to start a tech company. By 24 I was managing teams of 10 or more people and thought I was shit hot. I worked closely with a client and a wonderful, young mother named Diane said to me,

“You think you’re a great leader? You manage a team of super-motivated, freshly minted college students from top universities who work until midnight every night. Try managing a diverse team of people with different ages, education levels, incomes and motivations.”

I could see she was right. And for my sins I was then handed a mixed team that was both clients and Andersen employees. Of course it was infinitely more challenging. The clients didn’t have to do what I told them. They generally didn’t work late as many of them had families and most didn’t have the economic incentives we did. But of course they still cared about their jobs, their work product and their careers. But it was different and required different leadership styles. I had to do more listening and less talking (which for me is quite hard to do!)

I look around at the startups I fund. Many are run by relatively young people from top academic institutions who employ people who are similar in background and I think about this challenge of leadership where we have developed monocultures of young, single people of similar work ethic. I have some other portfolio companies with large telesales departments, call centers or even deliver truck drivers and it is awe-inspiring to see them develop leadership and empathy for the diverse set of people they employ.

The hardest leadership challenge is in the home. Any one of you who are a parent will realize that life’s ultimate test of leadership is raising your children. As with my early career, my CEO years or my years as a VC — I’m not perfect and I don’t pretend to be. But being a parent teaches you a lot about yourself. You realize that much of the attributes of a child are engrained from a young age and while you are their ultimate guide and role model you don’t really get to tell them what to do. It’s even harder than trying to tell college friends what to do.

And yet the pride you feel in watching their growth is like nothing I’ve ever experienced elsewhere. I’ve learned so much from parenting my two boys: Jacob who is 12 and Andy who is 9.

I’m a big believer in team sports because I believe that’s where many young people learn the important skills of teamwork, continually improving skills competency, playing a role in a broader effort than just yourself and dealing with both success and adversity. Sports aren’t for everybody but if your child gravitates towards team sports it’s a great experience.

When I was really young I was a star soccer player. I was small and had speed so I played center forward and scored more goals than my teammates. I was competitive. I hated losing. I loved the limelight of being the guy with the ball and the need to win.

So naturally I expected my boys to be the same.

Life doesn’t necessarily deal us those cards. My son Jacob is tall, sturdy and not the fastest guy on his team. He is patient and wise and would rather enable a team member with a great pass than to seek credit himself even though he personally wants to succeed.

I was thinking about all of this because we just finished his season yesterday with an all-star traveling team and it was really so wonderful to watch him develop. He wanted to play midfield this season but the coach asked him to play center defense. Our team was only average so many of the games consisted of the other teams playing much of the game on our side of the field.

So in his own way Jake became a team leader. This year I watched him emerge to direct traffic in the backfield. He made sure his left and right defenders had diagonal spacing — one playing up and one playing back. He made sure if we passed the ball on the opponent’s side of the field that his teammates pushed up to trap the offenders offsides and make them run back onside.

Jake would make sure the goalie stayed put in the box if he thought he or his teammates could get to the ball in time and he learned to back off when the goalie overruled him: Sometimes to good effect, sometimes to bad. But the goalie has the final say and Jacob respected that. He implicitly learned about the chain of command.

I’m not a crazy sports dad pushing my son to be the absolute best player on the team and to win every game. I always wanted him to be confident and competent enough to make friends, be a good teammate, get exercise and feel good about himself. The rest is up to him whether he wants to be super competitive or not.

His development this year was really heart warming.

Jacob as the first child isn’t much of a fighter or tough guy because he spent the first three years alone and the next ones with a “baby” brother. So this year we worked on “standing his ground” and the weekends of pride for me were watching him stand tough against much bigger boys trying to push him around or intimidate him. He wasn’t always as fast but he learned how to use his shoulder to shield the ball — even if the other player looked big enough to have driven himself to the game.

Jake is the opposite of me on the field. He can watch the ball come in fast and furious and calmly stand his position and wait for his other defenders to fill in their positions. He never lost his cool and in staying calm he strategically made it hard for other teams to take him. When I played I was always hell bent on getting in the face of whomever had the ball. I was aggressive and anything but patient.

Jacob and I are wired differently in sports.

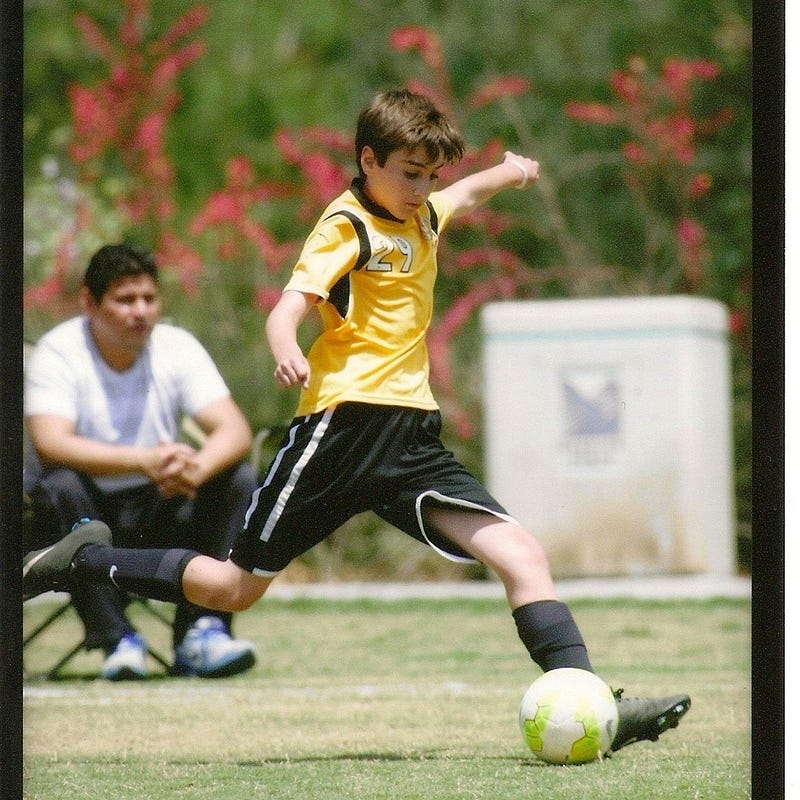

I watched him take ball after ball after ball in front of the goalie and calmly trap the ball and pass it out selflessly to his teammate. You can see this in the picture of him at the top of the post. I think maybe I preferred offense precisely because I didn’t have to be the guy who would be letting the team down if I screwed up.

One small thing I’m proud of as a parent is that our conversations about the games were truly never about winning. Maybe it was helped by the fact that we did so much losing :)) but each week we talked about just three things we were going to work on for that game. Three skills I wanted him to work on whether we won or lost.

One week it was how to get “under the ball” on a goal kick to make sure it cleared the offense who was always trying to cherry pick bad kicks. We worked on how to develop an offside trap and the need to direct ones teammates because it doesn’t work unless they pull up also.

We worked on shoulder checks, which are legal but as Tania will tell you my proudest moment of the season just might have been when Jacob got a yellow card. I know, that sounds bad. But it really showed me that he developed the confidence to stand up for himself and stand his ground. To be effective at standing your ground occasionally you need to cross the line. And that kid was a little bit more cautious every further time he was kicked the ball as in, “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen!”

Bring it.

I showed Jacob how to work the field in front of him when the ball was on the other side of the field and he had crossed midfield rather than hanging back. It was offense even while on defense. He even had a chance to boot one ball that nearly scored from midfield (it missed slightly left).

We laughed a lot. We had a lot of post-game lunches together. We commiserated every silly goal our team gave up and every loss we had. But we mostly joked about it.

I know parenting isn’t for everybody and my closest friend from growing up decided not to have kids and I respect the hell out of him for his personal decision. For me — I really have no greater joy than being a father and a husband.

And just when you think it’s all about your teaching your children how to better people, better sportsmen and better leaders you realize that it’s just life’s next lesson for you, too. Jacob isn’t “mini me” in sports so my own psychology doesn’t work on him.

I’ve learned to be more patient, accept our differences, not feel the need to win every time and enjoy the sport for what it is intended — building closer bonds.

And that we sure did. I love you, Jacob.