How to Get Yourself to Do Things

I have a special sympathy for sufferers of a particular human problem, and I get more emails about it than just about any other topic.

There are normal people, who get overwhelmed on those occasions when they have more obligations to fulfill than time in which to fulfill them. Then there are us procrastinators, who are constantly overwhelmed, because even when we do have time, we don’t make use of it until we no longer have enough of it.

Procrastinators are familiar with the perverse feeling of watching oneself create trouble out of nothing, essentially volunteering for penalties, embarrassment and regret. We’re kind of like those people who are so predictably, stupidly late for everything that the rest of us learn to tell them to arrive at seven o’clock for what is actually an eight o’clock appointment.

The difference is that the appointments we miss are with ourselves, which means there are no social consequences to limit the scope of our delinquency. We leave things on our lists for months. We let ourselves down in ways we would never let down others.

There is something diabolical about procrastination, and I don’t claim to have cured it. But I have somehow maintained a self-employed existence for almost two years now, which has required me to get better at managing it than I used to be.

I’ve had a bit of a breakthrough recently that I want to share with you fellow sufferers. I now see the problem in a much simpler way, and it is working.

Ignore your stuff

The first idea to get used to is that all of the “stuff” you need to do really only consists of things. What seems like a tangled cloud of open-ended obligations and old to-dos is actually a series of independent happenings in the world, which are best treated individually. By all means keep a list of your obligations, but understand that it is safe to ignore all of them while you consider (or do) one of them. In fact, it’s necessary.

This distinction between stuff and things is crucial. Once you’re treating each obligation as separate from the whole bundle of “stuff”, you can see that they each have a very predictable life cycle. Recognizing each problem’s seperateness brings it from the realm of the abstract and endless to that of the concrete and temporary.

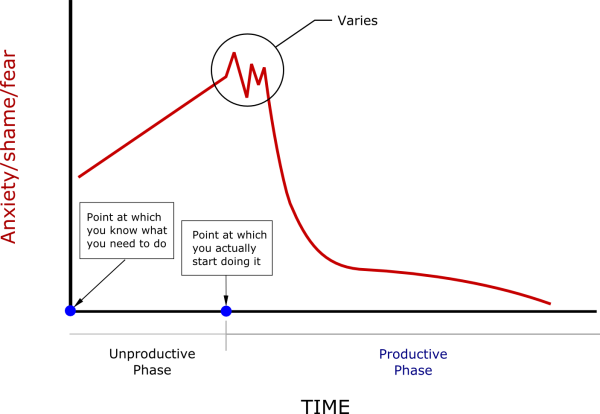

The typical life cycle of an individual thing looks like this:

As you can see, the problem starts when you know what you need to do, but balk on doing it. It grows in that space between the knowing and the doing. The anxiety, shame, and fear associated with the task rise as long as you live in that space.

Nothing else happens in this phase, except for your own suffering and aging. We can call it the Unproductive Phase. The longer this phase goes on, the more anxiety it generates and the harder the task itself appears to be.

At some point, often spurred by a crisis of some kind, you start to actually do the thing you’re supposed to do. It is here where the anxiety usually spikes — you are entering the Productive Phase, where failure, embarrassment, and the discovery of your own incompetence go from being future-dwelling spectres to real-time dangers. That’s why procrastinators avoid ever getting to this part.

But it doesn’t last long. You begin to realize that the task, like all tasks you will ever need to do, is finite and consists only of small, ordinary actions like Googling things, talking to people, reading, writing, sketching, printing, and cleaning up. The task begins to look patently doable. Your sense of capability swells and the fear recedes. This phase takes less and less willpower and courage as it goes on, until the task is in your past, and the life cycle ends.

When you extend the Unproductive phase, the anxiety continues to rise. Deadlines whoosh by, making it more and more absurd and embarrassing that you haven’t acted yet, which only paralyzes you further.

A serious procrastinator’s to-do life-cycle is often like this:

Now, keep in mind that this is just one of probably a few dozen things on your list at any given time, each of which can be in a different part of its life cycle. The procrastinator is always feeling overlapping fear from many sources, and begins to see them as a single problem: I suck at life. This makes him afraid to act, drawing out the unproductive phase of every task, ramping up the anxiety across multiple fronts and daring crisis to force him to act.

A severe procrastinator might have this experience:

Such a person is almost helpless until they know to treat each of those lines as a single, predictable course of events. Ultimately there’s no other way to deal with them. To tend to one we must ignore the rest while we do so.

Once we can picture the problem this way, there are a few conclusions we can draw:

The smart thing to do is obvious: end the Counterproductive phase as soon as possible. This end is always a concrete, bodily action, often taken with some trepidation: opening up the word processor, dialing a phone number, or getting out a piece of paper so you can sketch up a plan.

The moment you start acting on something, you are at the beginning of the end of the anxiety associated with that thing. Many or most procrastinators are pessimists, habitually overestimating the difficulty of what they are avoiding. They think doing it is the hard part. But not doing it is much harder. The odd task that turns out unexpectedly hard doesn’t change anything — the counterproductive phase will always be counterproductive, and the anxiety will always shrink with action.

The moment you start avoiding action again, the process restarts. When you halt your work on a given thing due to fear or aversion, you are re-entering the nonproductive phase. Physical action ceases, and pointless rumination begins. Anxiety will rise until you enter the Productive Phase again. This is a good reason not to switch tasks unnecessarily. Push one thing at least until it is coasting, if not finished.

You can’t see an obligation for what it actually is until you’re doing it. The rising anxiety associated with a particular thing comes from a misapprehension of what it will actually be like to do the work. Work itself is made of concrete, small things like phone calls, forms, conversations, reading sessions and writing sessions. The anxiety associated with the work is made of abstract, big-picture emotional concerns, about reputation, legacy, anxiety for the future, self-esteem, comparisons to others — worries about who you are, rather than what you’re doing. Once you enter the productive phase you enter the world of the concrete and finite, putting your related existential despair on the backburner.

You finish a thing by starting it until it’s done. The critical point is always where you enter the productive phase, and this is accomplished by starting alone. Finishing is only a matter of starting from where you are, as many times as you have to, until it’s done. Most of the resistance and stress is piled up on the boundary between the phases, and so once you’ve started it’s mostly behind you. [Thanks to Leo Babauta for this principle.]

It is not hard to figure out how to start. Some of you procrastinators may be thinking, “Well that’s GREAT if you KNOW what you ought to be doing. I have no idea what I ought to be doing!” This is a lie procrastinators tell, fooling themselves and no one else. Any reasonable, honest person can figure out where to start. When you know where you want to get, and you actually intend to get there, it’s easy to identify a sensible starting point. And the further you venture into productive territory, the clearer the map gets.

The two most important insights, however, are the first ones:

- Ignore your “stuff”; focus only on things

- When you don’t know what to do, get one of your things past the starting point

This might look like a convoluted way to say “Just do it.” But it’s more sophisticated than that. Whenever you feel the creep of anxiety, remember the shape of that first graph, and where you are sitting on it. Just remembering it reminds you that relief is never far off, if you want it.

The simple map implied by that shape cuts through the procrastinator’s two main problems. Firstly, that “stuff” is overwhelming and unpredictable (in a way that things are not.)

Secondly, it turns on its head the faulty assumption that underlies procrastination, which is that things can only really go wrong if you start working on them. The reality is the opposite: things are already going wrong, and there’s only one way to make them go right.

***